“SWISS NANNY” TRIAL: FIRE INVESTIGATION KEY TO THE CASE

At approximately 5:16 p.m. on December 2, 1991, a frantic Olivia Riner, a Swiss nanny, telephoned the local police department to report a fire at 5 West Lake Drive, Thornwood, New York, the residence of Denise and William Fischer. The area is comprised of several small hamlets and villages, and the operator connected Riner with the wrong police department. The police department she reached could not locate the street within its jurisdiction and called her back to tell her so. The desk officer tried to obtain more information pertaining to the exact location of the house. At this point, the police department realized that the call should be directed to the Mount Pleasant Police Department. The call was referred, and the Mount Pleasant Police Department dispatched police and fire personnel to the house.

According to the police report, Riner was feeding the three family cats in the laundry room on the first floor. One cat finished eating first and left the laundry room to go to Riner’s room. (He liked to lie on her bed.) Shortly thereafter, the cat came back to the laundry room in an agitated state. When Riner went to investigate the reason for the cat’s reaction, she discovered a fire on her bed. She also noticed that the sliding window in her bedroom, which normally was closed, was open. She went upstairs to the kitchen to get the fire extinguisher, returned to her bedroom, and extinguished the fire on her bed.

After this had occurred, Riner noticed that the door to six-week-old Christy’s room was closed. Christy was the child of Denise and William Fischer and Riner’s charge. Riner tried the door and found it locked. ITie smoke alarms downstairs and in the hallway then went off. Riner reported that the light in her bedroom did not go on when she pushed the switch. She dialed “O” to report the fire; it was approximately 5:16 p.m.

As Riner put the receiver down after speaking to the police the second time, she turned and saw John Gallagher, the boyfriend of Leah Fischer —the daughter of William Fischer from a previous marriage — standing there.

According to the police report, Gallagher asked Riner where Christy was. He grabbed the fire extinguisher Riner was holding, ran to the infant’s bedroom on the first floor, forced open the door, and found the infant sitting in a plastic baby carrier on the floor. Believing the baby to be dead, he left the room. The police arrived shortly thereafter and also reported that the baby was dead.

When the Thornwood Fire Department arrived shortly after the police department had forwarded Riner’s call, members found a heavy smoke condition. Shortly, a ball of fire vented out the south side of the house. Its origin point was Leah’s room, which was adjacent to Riner’s room. Fire Chief Greg Wind took command of the firefighting operation and the fire quickly was extinguished.

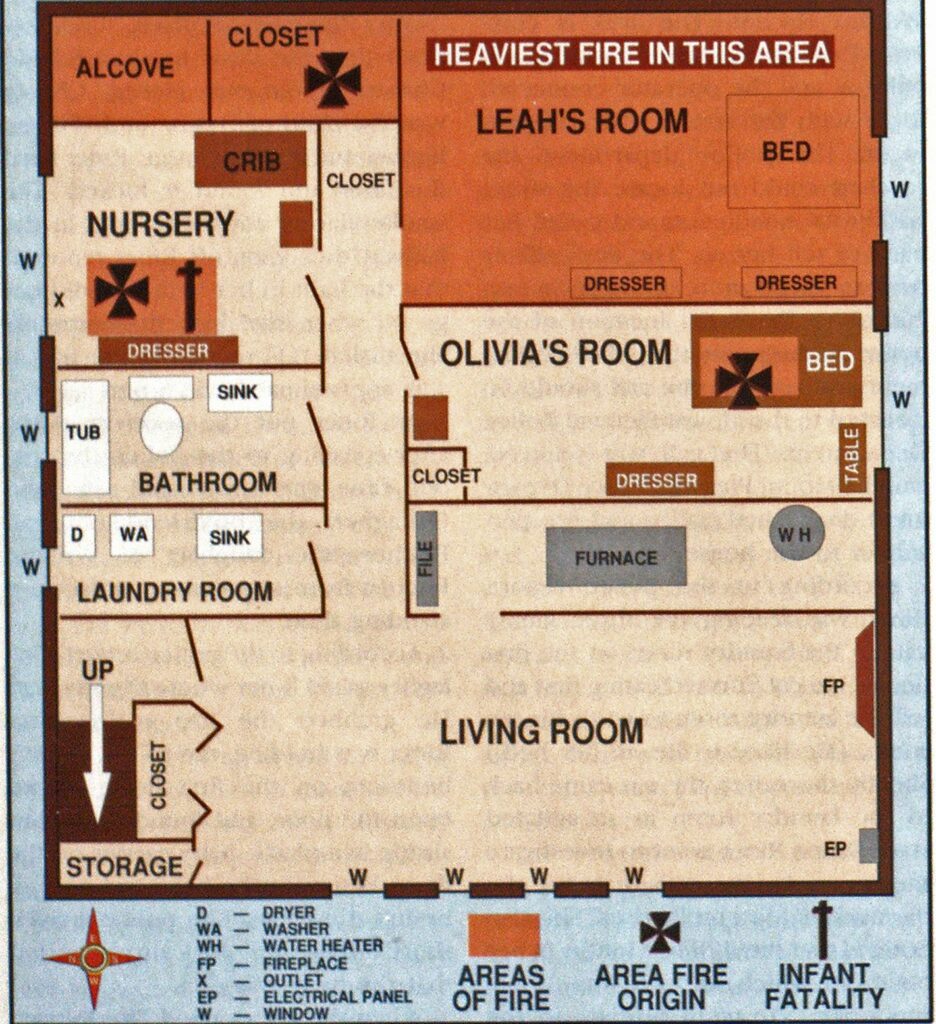

It later was determined that there had been three separate fires—in Leah’s room, in the nursery, and in Riner’s room. After the fire was extinguished, local police authorities labeled the fire arson. The only person believed to be in the house at the time of the fire, Olivia Riner, was arrested that evening and charged with arson and murder.

A chain of inexcusable incidents was to unfold during the sevenmonth, much-publicized arson/homicide trial that followed. Subsequent reports of the incident were distorted to cover up incompetence by local and county authorities. From beginning to end, virtually every written and unwritten rule of sound police and fire investigative procedures was broken, distorted, or ignored to make the “means justify the end.” The prosecutorial case against Riner uniformly misrepresented the facts.

As it turned out, this case also illustrates how crucial it is for fire investigators to identify, secure, and preserve any item or material that possibly could be considered evidence. Olivia Riner ultimately was found innocent by the jury, which based its decision on evidence gained by an outside investigation firm through skillful investigative techniques and unfaltering teamwork. The victory, however, was bittersweet, since the party or parties responsible for this heinous crime are still free.

FISCHER HOUSE — FIRST FLOOR

ANATOMY OF THE INVESTIGATION

Our forensic investigative company, Peter Valias Associates Inc. (PVA), entered the case on December 8, 1991, at the urgent request of attorney Laura A. Brevetti, of Morrison, Cohen, Singer & Weinstein of New York City, legal counsel for F. F. AuPair Services, the agency through which the Fischers obtained Riner’s services.

Several allegations of impropriety involving the manner in which the local police and the prosecutor’s office handled the initial investigation of this incident prompted the defense to question the charges made against Riner. PVA received permission to conduct an investigation at the Fischer home several days later. (Since our organization was a third party in that it did not represent the homeowners or a tenant on the property, permission to examine the house had to be obtained through the court.)

Inspection, Day 1. On December 11, we conducted an investigation of the premises that included the house, a shed, and the contents of the rear yard. During the initial walk-through of the premises, we carefully noted the existence of any evidence that might be perishable or may have been disturbed during the evening of the fire. Since we wouldn’t be back for at least six hours, we tried to examine all the potential evidence on the first inspection. Some evidence can diminish with time or possibly could be taken away.

Our investigation uncovered that there were three separate fire sites. The fire patterns were heaviest in Leah’s ground-floor bedroom and closet at the southeast comer of the two-story, wood-frame house. A fire also had occurred in Riner’s groundfloor bedroom at the south side of the house, and a separate and distinct fire occurred in the infant’s nursery on the ground floor at the northeast side of the house. This finding of three distinct, not interconnected, areas of fire origin indicated that the fires were not accidental but incendiary.

Since basic fire investigatory techniques must be employed and every possible ignition source must be ruled out before a fire can be declared incendiary, we examined the potential accidental heat sources in the first-floor area. They included the electrical panel; fireplace; oil-fired, warm-air furnace; and propane-fired, domestic hot-water heater. All the possible ignition sources, we found, did not cause any of the three separate fires.

Inspection, Day 2. This inspection began with a detailed search of the entire grounds surrounding the premises. The fire patterns on the exterior of the building then were examined, and the entire fire scene again was scrutinized.

Notes relative to and photographs of the premises were taken before any evidence could be disturbed; all evidence was logged with respect to location. Every room was examined in detail and measured so that a floor plan of the house’s interior could be reconstructed.

After our investigation was completed at the end of the second day, all evidence was taken to our laboratory facilities, where it was separated and evaluated. Tests for accelerants on some items indicated the presence of paint thinners.

At the same time these tests were being done, we had arranged to examine the evidence being held by the Westchester County crime lab in Valhalla, New York. Members of our staff visited the crime lab to examine and photograph the State’s evidence and to note the condition of the items. This examination, however, created more questions than it answered. For example, there were no fingerprints or any direct evidence implicating Riner. It was alleged that Riner had splashed an accelerant (turpentine or paint thinner) from a plastic soda bottle onto the floor. Yet, not one drop of accelerant was found on her shoes or clothing. If she had splashed the combustible liquid as charged, at least one drop of the liquid should have been found on her clothing. We continued to look further.

(Photos courtesy of Peter Valias Associates Inc)

Test bums. We arranged to conduct test burns at a building scheduled to be demolished near our Endicott, New York, office. Carpeting similar to that found in the Fischer house and the paint thinners identified by our forensic lab were used in the burns. The building selected was surveyed before the burns to ensure that it could be used to closely recreate the fire area of the Fischer house. The interior of the selected building was furnished to match the Fischer house furnishings as closely as possible. The test burns were documented on videotape as well as on 35-mm film.

The objective of the test burns was to document the sequence of events that occurred at the Fischer residence. We wanted to answer questions such as the following: How much time would it take to set three fires in separate rooms without being noticed? What was the most logical sequence of the fire? What part did certain factors/items in evidence— overlooked by local authorities— play in the sequence of events? We also hoped to identify the most probable suspect(s).

FINDINGS

Among our findings were the following:

- The floor plan of the Fischer house was conducive to an intruder’s going about the bedroom area of the ground level undetected. In addition, the cover of darkness and heavy shrubbery about the home provided easy cover for an intruder.

- Once inside the house, accessing the three bedrooms in which the fires had occurred involved walking no more than three steps from one room to another.

- The Westchester County police and prosecutor overlooked an important piece of physical evidence: apartially burned cloth diaper, which we recovered from under Riner’s bed, adjacent to the wall. The diaper was found to be consistent with other diapers found in the nursery. Analysis of the cloth through gas chromatography by Stewart James, a forensic scientist at our Ft. Lauderdale, Florida, laboratory found evidence of paint thinner and the residue of a fire extinguisher dry’ chemical. Test burns enabled us to conclude within a reasonable degree of scientific probability that the diaper was the burning object on Riner’s bed. The test bums recreated the protected area on the bed cover when the burning diaper was either placed or tossed on the bed, further confirming Riner’s testimony that she saw the fire on the bed, went upstairs to the kitchen, retrieved the fire extinguisher, and used it to put out the bed fire.

Using an actress of the same height and weight as Riner, we were able to recreate in our tests the setting, discovery, and extinguishment of the fire in Riner’s bedroom, confirming her story that she used the extinguisher on the fire. In addition, the burned diaper made the same pattern on the test bed as it had made on Riner’s bed in the Fischer house.

Finally, we suspected that in all probability the perpetrator entered the premises through Leah’s sliding bedroom window, ignited a fire in the closet in the room, and exited the room. Then he/she went to the nursery across the hallway and poured a combustible liquid in the area of the baby and ignited it. The rolled diaper, used to prop up the baby’s head, was ignited and either thrown or placed on Riner’s bed in her bedroom across the hallway. The perpetrator then exited through either Riner’s bedroom window or the window in the bathroom across the hallway, also found unsecured during our inspection.

Many hours of reading and rereading the transcripts and other documents constituted the follow-up investigation after the on-site inspections.

- The State’s case was founded on the premise that the Fischer residence was as secure as a fortress. Our investigation, however, found at least three unsecured windows accessing the ground floor area of the fire origin. We found that the sash lock on the window of Riner’s room was unlocked at the time of the fire and that the lock on the bathroom window was missing. The interior screen of the bathroom window, in fact, was found in the tub, where it rested during the fire—a finding confirmed by the melted plastic curtain on top of the window sill and edge of the screen. (If it had been removed by firefighters, it would not have had melted plastic on it.)

(Note: The videotape used as court evidence, unlike this poor-quality photo, was very clear.)

We had obtained from the prosecutor’s office the videotape taken by the Westchester County Fire Academy staff the night of the fire (these tapes are used to critique fires). Reviewing the tape, we noted what appeared to be an open window in Leah’s bedroom. This finding contradicted the testimony of local investigators, who testified that they had checked the window after the fire and found it closed and locked (they did not document this in their reports or photographs). After discovering this open window in the videotape, we used special video equipment to freezeframe the portion of the tape showing the open window frame and recorded the section with 35-mm prints.

IMPACT ON THE TRIAL

The issues of the condition of the windows and the lack of security of the premises at the inception of the fire proved crucial at the trial. During the deliberation period, jury members asked to see the videotape— more specifically, the position of the window at the time of the fire. This evidence was one of the factors that led the jury to believe that someone else (instead of Riner) deliberately could have set the fires.

Skillful, diligent origin-and-cause investigation of the fire scene in conjunction with careful, well-executed, and planned follow-up investigations brought this case to a fair conclusion. Fire investigation is a very complex and demanding profession. You never can spend too much time on an investigation —especially when an individual’s freedom is involved. Personal and gut feelings have no place in the fire investigation field. Only facts based on sound forensic analysis should be used to make a conclusion. Allowing one’s mind to wander or to speculate on half-truths and innuendoes can bring only disaster.