BY ERIC LINNENBURGER

Being first due is like no other feeling in the world. Adrenaline is high. The sirens are screaming as you process dispatch information—some of it useful and some not. You create a picture in your mind about what you will face. You talk in the cab about potential assignments and priorities. When you arrive on the scene, you must take that preconceived picture and match it up with what you see.

You have seconds to put all the pieces together, adjust the plan, and articulate it to your crew and to the incoming companies over the radio. The spotlight is on you and your job is critical. As one of the late Phoenix (AZ) Fire Department Chief (Ret.) Alan Brunacini’s timeless tactical truths says, “Most of the time on the fireground, the first five minutes are worth the next five hours.”1 First due is first due, whether you work in a large metropolitan area or a small rural area. No matter how big or small the event or how many resources are coming, there is always a first due, and it always comes with similar challenges.

- Fire Conditions vs. Victim Survival: Pushing Paradigms and Procedures

- Search and Rescue by the Numbers

- The Oklahoma City Story: Tracking Grabs with Firefighter Rescue Survey

What happens when you are faced with that “career event” as a fire company? This is the type of incident where you know you are about to be overwhelmed and outmatched. This changes from department to department. For one department, a single victim rescue from a balcony could be enough to tax resources and be a pinnacle event. For another department, that first-due company will have the resources and training to make the rescue and attack the fire without missing a beat. These events are all relative, based on factors including resources, staffing, and training.

Some people go through their entire career without that big first-due event, but we must prepare as if it is right around the corner. As a company officer, my “big one” came a few years back. I had been a captain for more than four years and a lieutenant for the same amount of time prior to that with the Westminster (CO) Fire Department. I was far from being an expert but had a fair number of “good” first-due fires under my belt as a company officer. However, this one was like nothing any of us had experienced before.

Background and Intent

For perspective, we are a six-station, full-service suburban department in the Denver area. Our daily dedicated staffing is five engines, two trucks, five fire transport medic units, one battalion chief, and one safety and medical officer. Our engine/truck minimum staffing is three personnel, and two firefighters ride each medic. At the time of the incident, we had mutual-aid agreements with neighboring departments in the region. We have since evolved into a robust automatic-aid region using a closest unit CAD to a CAD dispatch system.

The purpose of this article is not to serve as an after-action review (AAR) for this event or critique the actions. Many reading this have experienced far greater events and on a more frequent basis. This was a major event for my small organization but may not be for others. The intent is to acknowledge the challenges of being first due and hopefully use this experience to offer some basic tools for company officers and their crews as they prepare for that overwhelming first-due event.

The One We Still Talk About

It was a warm summer night at approximately 0200 hours. We were dispatched to a large, three-story multifamily garden apartment complex. This is one of those “nocturnal” complexes we visit frequently for fire and EMS calls. The fire building was the largest in the complex. We knew this building well as it was the only one with an elevator, so it housed many mobility impaired residents. It was an H-shaped building with 69 total 600- to 1,200-square-foot apartments.

Our station is close: 1.5 miles away with minimal traffic at that time of night. We were in quarters sleeping at the time of dispatch. My crew consisted of a three-person truck (quint) and a two-person medic unit staffed with a firefighter paramedic and a firefighter EMT. The initial response group was three engines, one truck, two medic units, one battalion chief, and one safety officer. Dispatch advised us multiple callers stated there was heavy fire and people were jumping.

When we arrived, we had heavy fire conditions on multiple sides (photos 1 & 2). The external stairwell and breezeway that served this end of the building were involved floor to ceiling and fire was already into the attic. The apartment units on the long center run of the building are all single, front-to-back units with front doors on the courtyard side opening to a shared balcony walkway and bedroom windows on the parking lot side.

1. The B-side stairwell breezeway. Heavy fire on arrival made self-evacuation impossible for many people. Trapped victims needed rescue from bedroom windows and balconies on both sides of the breezeway. (Photos by Eric Roth unless otherwise noted.)

2. Front doors opening to a shared walkway and balcony on the courtyard side, which was the D side. Many occupants were unable to evacuate and pushed to windows in the rear of their apartments. Many who evacuated left doors open, which resulted in rapid outside-in fire spread.

The front door egress for the units on the long side of the building had fire running the shared balcony walkways and pushing into the units and the attic and void spaces above. The front doors to the units on the short side of the building opened to the stairwell and breezeway involved in heavy fire. If the occupants were unable to get out immediately, they were trapped and pushed back to bedroom windows and balconies in the rear of their apartments due to heavy fire blocking front door access.

We parked the truck on the long side of the building, where we had access to the bedroom windows and the open stairwell breezeway. This was eventually designated the B side. Police officers were actively pulling people out of garden-level windows. People were hanging out of windows in need of rescue from the second and third floors, including a father in the most threatened exposure ready to throw his baby from the third-floor window. The medic crew pulled up short and positioned in the parking lot of the short side (A side) of the building to not block incoming fire apparatus and so they would have the ability to exit the scene if patient transport was needed.

I gave a brief, albeit poor, arrival report letting incoming companies know the fire conditions and that we would be all hands with window rescues from ground ladders. I established command and we went to work.

I had my firefighter stretch a 2½-inch preconnect to attempt to knock down the fire in the stairwell and to protect the victims hanging out of windows. This line would buy us time to set ladders and, if we could control the fire in the egress, allow people to self-evacuate.

My engineer engaged the pump, charged the line, and established a water supply. He then set the aerial for eventual defensive operations.

I did a face-to-face with my medic crew at our truck where they advised me there were people in need of rescue on the A side of the building where they parked. I sent them back to the A side with a ground ladder to work on window rescues. This was a competent crew, which included an acting company officer and a strong firefighter, so I trusted them to work independently.

As part of a three-person crew, I was the only one available to begin the rescue process on the B side. Fortunately, our second due was an engine company that arrived right behind us. They assisted with the rescue operation on the B side. We set ladders and began removing the known victims from the upper floors, starting with the most threatened.

By this time, the battalion chief arrived, assumed command, and assigned me to a division supervisor role on the B side of the building. When the known window rescues were complete, additional companies arrived and we coordinated a vent-enter-search (VES) operation of all windows in that end of the building unable to be searched or evacuated through the front door. Many of these VES entries only consisted of a quick sweep of the room and hall before crews were pushed out by high heat and preflashover conditions. Twenty-plus VES entries were made through upper-level windows on the A and B sides.

In those initial minutes of the incident, there were eight ground ladder rescues, including one unconscious victim located deep in an apartment under clothing and other items to shield the smoke and heat. There were also several people rescued out of lower-level windows by police officers. There were 19 injuries that we know of, including several critical from burns or jumping from upper levels. Most of the injuries were significant enough to require ambulance transport. There were two fatalities.

After the searches and evacuations were completed, crews were pulled out and we transitioned to a defensive operation with ladder pipes and exterior handlines. By the end of the event, we had the equivalent of four alarms to bring the fire under control and handle the EMS component.

The challenges of this call as the first-due company were abundant. Simply deciding where to park and how to engage in the operation was overwhelming. We were outmatched by the amount of work that needed to be done but formulated an initial action plan, worked to the level of our resources and capabilities, and dug in where we could make the most positive impact on human lives and for the long-term success of the operation.

Prepare Before the Event

How do you prepare for big events? I argue that you do so the same way you prepare for all events—by building strong crew competency, individual competency, and a solid understanding of how your actions affect the overall incident. Do not overthink it or feel you need to draw up bizarre scenarios to match every possibility. Instead, focus on the many controllable components that can make up any fire incident.

The skills used in these events are no different than those practiced in training or used in everyday “bread-and-butter” type fires; there are typically just more of them needed and spread across a more complex scene. Make the skills and a calm, competent mindset second nature. It is obvious that preparation will involve significant hands-on training, but it goes beyond that to be a high-functioning crew. Expect the unexpected but understand you can work through anything with sound fundamentals and common sense.

Training

Focus on basic skills such as ladder work, victim removal, hose deployment, and communications. Practice these skills outside of just the sterile drill ground. Stretch around cars. Extend lines. Be proficient beyond preconnected lines. Ladder around trees and other overhead obstructions. Practice radio communications from the cab while mobile and while masked up.

Train with intention based on proven data and science. Use resources like the Firefighter Rescue Survey2 and UL FSRI to guide training and train within the margins. According to the Firefighter Rescue Survey, the greatest number of rescues occur in the initial minutes by the first-in crew and correlate with the greatest victim survivability. In large events I have been a part of, it is the fundamentals that make a difference. It is important to practice new techniques, and any training with the crew is beneficial. Still, it’s important that you ensure proficiency with the known difference making high-percentage skills first. This includes the ones where skill and speed save lives, like ladder work, search and rescue, and quick water application (photo 3).

3. The next day. The night of the fire, the parking lot was full. This made apparatus placement, hose deployment, and water supply challenging. Overgrown trees against the building, along with other landscaping features, made ground ladder operations difficult as well. Long hoselays were necessary through the courtyard and around overgrown vegetation and other obstacles. This is all quite common and possible to prepare for. (Photo by Top Shots Media.)

There is no substitute for hands-on training, but we must go further with our crews. We can also train our minds. Constant crew engagement through kitchen table and apparatus cab conversations in an open, low-stress environment is important for gauging the understanding of the crew and creating leader’s intent. Do not assume everyone is on the same level or has the same skill set. Spark conversation by reviewing policies together, reviewing LODD and near-miss reports, completing AARs, and hot washing even seemingly simple events. Proficiency with the skills does us no good unless everyone knows when to use them and learns to anticipate the dynamic fireground and their officer’s intent.

Preplan your first-due area. Understand risk profile. Train on “go/no-go” decision making. This applies to the entire crew. The officer will make the call, but the entire crew must be on the same page and understand the objectives and risks. All crew members have an obligation to speak up if they see things differently. In our case, the crew was familiar with this building, its occupants, and its layout. We reduce our risk significantly just by understanding the known hazards, building type, and layout.

Focus on controlling what you can control. Mental bandwidth is an issue for leaders on and off the fireground. The fireground is not the time to struggle through simple tasks. In Thinking Fast and Slow, Daniel Kahneman says, “As you become skilled at a task, its demand for energy diminishes.” Studies of the brain have shown that as skill competency increases, fewer brain regions are even involved in completing the task.3 This frees bandwidth and improves situational awareness.

If the leader ensures the crew is proficient in the task-level skills, he can focus on the most dynamic aspects of the scene, such as reading the cues, making decisions, and ensuring crew accountability. The company officer is no different than the coach on the sideline. The fireground is the time to call the play, not teach the play.

The importance of physical fitness cannot be overstated. These events are long and will result in more work cycles than most are used to. Couple this with an increased release of adrenaline and cortisol, and you could be set up for a catastrophic event. Physical fitness is controllable. Take care of yourself to take care of others. It is impossible to make good decisions if all your focus goes into breathing.

Relationships

Know your people and their capabilities. Accountability goes beyond knowing where your people are. You also need to know what they are capable of. This is an active and ongoing process. Know the obvious, like fireground strengths and weaknesses, but also be aware of the not so obvious, like what kind of day they might be having and how physically and mentally healthy they currently are. Encourage a firehouse culture where people interact rather than hide in the bunkrooms. It pays dividends on the fireground.

In our case, I knew I could trust my single firefighter to work independently on a large handline without supervision. I also knew that as a department we had been consistently drilling VEIS and victim removal so, though not ideal, I felt confident in my medic crew operating independently and out of my view on a different area of the building to perform window rescues.

Relationships go beyond your individual company. Train with other companies on your shift and beyond. Build relationships off the drill ground. While in the middle of this VES operation, two mutual-aid companies were assigned to me. It was a relief to look up and see two officers with whom I had long friendships walking up to the scene with their crews. Already on a first-name basis and understanding one another’s backgrounds gave us confidence and made our operation safer and more efficient. These intangibles may be hard to measure, but they matter.

Know the Game

Understand and be proficient in the system you work within. Know the resources available and what your capabilities are. Every organization is different. Do not dwell on this; just accept it and understand what you are working with. We all witnessed the FDNY recently perform heroic lifesaving rope rescues on multiple high-rise fires. This is a well-trained and practiced skill for them. It does not mean it will be for all departments. Put your time and energy into becoming proficient in the areas where you can make a difference. Understand the challenges in your community and prepare to your organization’s highest level of competency.

Know and follow procedures, practice radio discipline, and be engaged in the day-to-day work. Understand how your company fits into the bigger event as it expands. It is so easy to get tunneled into the task level and only worry about yourself and your crew. Remember, you are part of a bigger team and greater mission, so operate that way every day. Understand the expanding incident command system, communication plans, and other priorities.

Game Day

You may feel overwhelmed or fear making the wrong decisions. This is normal! We all want to succeed. Trust in your experience and training. If you put in the work and have a solid foundation of experiences, you can work through an event and make good decisions. Many in the fire service should be familiar with research psychologist Gary Klein’s important work on intuitive or naturalistic decision making, also referred to as recognition primed decision making. The foundation of his research was studying fireground commanders and their ability to pull from past experiences, either firsthand or simulated, to read cues and make decisions quickly.4 The cues will be all around you. You do need to be prepared and open to receive them. Also, expect to make mistakes. Just be capable of recognizing them, put your ego to the side, and adjust.

Expect Chaos

These scenes are incredibly chaotic. We expect the public to be excited at an emergency scene, but when people are trapped everything escalates. In the case of our incident, the screaming was not just loud but a tone I had never experienced, and it was everywhere. We could hear screaming from the people on the ground and from those hanging out of windows and jumping from windows.

Be cautious entering the scene and maintain situational awareness as you set apparatus and prepare to go to work. We had trouble even making the turn into the parking lot because of the number of people obliviously running next to our truck and screaming and pointing. We had people trying to take ladders off our truck when we parked and even away from windows with firefighters inside them.

It is imperative that the entire crew, especially the company officer, remain calm and not allow the crowd to distract them. Lives depend on it. The people walking around out of the hazard zone are not your concern. The first-due officer must have command presence and take control of the scene—or it will control him. Calm is contagious for your crew, the incoming companies, and the bystanders.

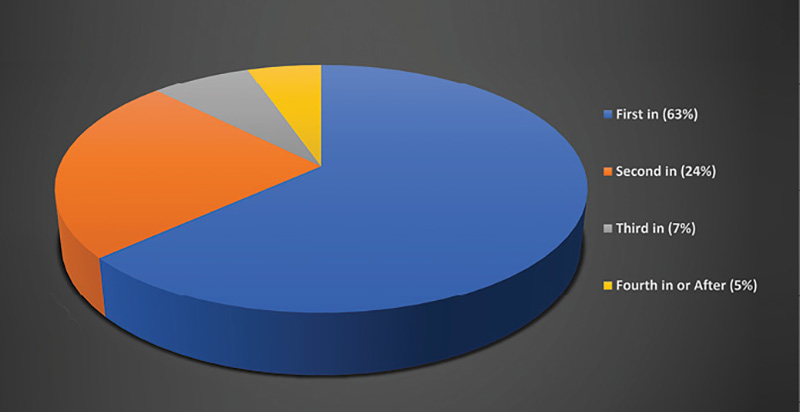

Figure 1. Annual Order of Crew That Located Victim vs. Total Recorded Rescues

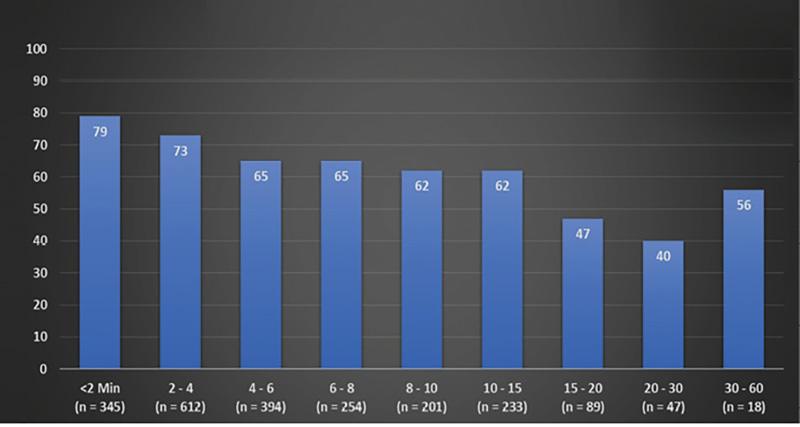

Figure 2. Time vs. Survival Percentage

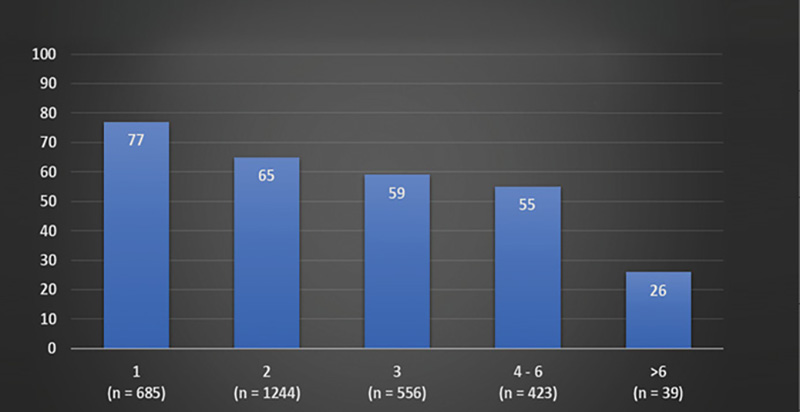

Figure 3. Number of Rescuers Needed for Removal vs. Survival Percentage

Figures 1-3. These are Firefighter Rescue Survey’s “The First 3,000 Rescues.” The data shows that we must train to proficiency within the margins. The actions of the first due matter. Speed also matters, for offering victims the best chance of survival and for protecting our rescuers. This last slide proves that small departments with limited resources can accomplish a lot. “Real life” indicates that most rescues are being completed with one or two rescuers.

(Source: Firefighter Rescue Survey.)

Set the Scene up for Success

The first-due company officer can have a significant impact on the outcome of the event by setting it up right. A solid size-up and arrival report is critical for the incoming units, especially the eventual incident commander (IC). One of the biggest challenges at our incident was confusion as to the naming of the building sides and apparatus locations. The building was large and only part of it was visible to the IC. I, as the first-due officer, could have cleared up so much confusion for the incoming battalion chief by simply naming the side I was operating on.

The arrival should be practiced, just as you practice stretching hose or throwing ladders. Anticipate what you will say prior to arriving on scene. If you, as a company officer, have the authority to upgrade the alarm, do so. Even a single confirmed victim should prompt an upgrade in most systems.

Also, remember that these fire incidents can quickly become mass-casualty incidents (MCIs). EMS resources must be at the top of this list and in a forward operating position. Battalion Chief (Ret.) Anthony Kastros, Sacramento Metropolitan (CA) Fire District, speaks frequently about doing the whole job—closing the loop.5 Making a rescue and dropping the victim in the front yard is not the end goal. Our goal is for the victims to receive rapid medical treatment and transport so they can return to their loved ones.

Every situation will be different, and it is understood that communication procedures differ from department to department. Here are a few tips to help set the scene (and incoming IC) up for success:

- Paint the picture with a concise size-up and arrival report.

- Be mindful about apparatus placement when you’re anticipating an expanding incident.

- State your location (if it’s not obvious) and designate the building sides.

- Verbalize initial actions, objectives, and immediate hazards.

- Announce your water supply status.

- Order additional resources.

- Declare an operating strategy and establish command.

Engage

A good instructor in a command and control class once encouraged us to simplify the problem. We were all overthinking our actions and stretching resources to achieve unrealistic goals. This is easy to do in a static classroom setting where time stands still and real lives are not at risk. He reminded us that every fire has three basic problems, or a combination of the three:

- People.

- Fire.

- Smoke.

Of course, it is ideal to address all the problems simultaneously, but we know this is not always possible; it’s dependent on the resources available and the conditions. As the first due, you must determine where you can make the most impact with the resources you have available. Any threat to people will be your immediate priority. Whether you go directly to removing them from the fire or choose to take the fire away from them will depend on your situation.

Make a sound plan and articulate it so others know. Work within your means. Focus on controlling the many small problems within the large event. It is no different than triaging an MCI. Read the cues the scene offers you. You will never have all the answers and you may not make all the right decisions. Just have alternate plans ready and be flexible enough to adapt.

The Aftermath

It’s Not Over When the Fire Goes Out

These high-profile events escalate quickly, especially when the investigation extends beyond the authority having jurisdiction. When state and federal agencies get involved, things get real, and fast. Your responsibilities are not over when the hose is reloaded or even when you get relieved at shift change, especially for the first-arriving crew and company officer. Not even the backseat firefighter is protected from this.

Everyone should be ready to document their experience and be interviewed multiple times. This is something you can prepare for. As leaders, we must ensure our people understand the seriousness of the job and are trained to at least a basic level regarding documentation, evidence preservation, and legal responsibilities. It should also be understood that these events can drag on for years between potential criminal and civil litigation. In fact, it is common for crews, especially company officers, to be subpoenaed to testify years down the road.

These Events Are Messy

We envision big events where we get to use all our skills, almost like a major sporting event. In these imaginary scenarios, we will be back at the firehouse having press conferences and celebrating with our teammates. This is not the reality. While we should be proud of our accomplishments, it does not always feel good.

In my experience, I have defaulted to the mistakes I made. Even though I knew the injuries, fatalities, and property loss were not my fault, it was hard not to be critical of myself. We take ownership of our responsibilities and are prideful about our culture when it comes to learning from experiences. This is a good thing; just be aware of our tendencies toward perfection and remember our environment is never stable. Striving for the “perfect event” is setting yourself up for disappointment.

Beware of the armchair quarterbacks who were not there, both within your organization and beyond. These are high-profile events. They will be all over the media and people will talk. You will hear it directly, but you might also hear it in whispered side conversations. Some are envious they were not part of it. Some really do think they could have done things better. In the end, expect the noise and understand it is human and fire service nature. In our case, the situation was amplified by the long-lasting investigation and the fact that we were restricted from sharing information about the event, even to the point of not allowing a formal public AAR to be presented. The best way to combat the chatter is for those who were there to honestly share these experiences with others so they can gain perspective and learn from the boots-on-the-ground experience.

These days, we focus a great deal on mental health in the fire service—and rightfully so. It is easy to point to the obvious stressors that are built into the job, such as the death of children or major trauma. But we must recognize the successful events that have happened as well as those that have not yet happened. We all have a responsibility to take care of one another as a crew. However, as the leader, it is your job. Personally, I may have failed to recognize the significance of this at the time. It is too easy to get wrapped up in the aftermath of the event and assume everyone is okay. Appreciate the significance of these events from their perspective and check on your people.

Putting It All Together

Being first due to large events will always be the most exciting and anxiety-inducing experiences in the fire service. Success of the first due is paramount to the success of the event. We want to be prepared for every scenario we may face and perform well. The bottom line, though, is that we cannot prepare for everything. However, we can prepare for the many predictable aspects of the fireground. We can get the physical and mental reps in that allow us to put the pieces together on game day. The fireground is really a bunch of smaller challenges that make up the larger event.

You, as first due, will not be able to control the entire event. Here’s a checklist of what you need to think about and prioritize in your approach:

- Set the scene up for success.

- Engage where you can do the greatest good using the resources available. (The big event is like the smaller event; it just has more challenges and may extend operational periods.)

- Understand the game you are in to increase your chances of success.

- Train for your department’s challenges.

- Understand your systems and resources.

- Model from others, but do not try and be something you are not.

If you are intentional in your preparation, you increase your chance of success by building a pattern recognition that allows you to read cues and leads to better natural decision making and confidence.

ENDNOTES

1. Brunacini, Alan, “The first five minutes are worth the next five hours,” Fire Engineering, January 1, 2010. bit.ly/3VGiucx.

2. “The First 3,000 Rescues,” Firefighter Rescue Survey, 2022. bit.ly/3PFWnPk.

3. Kahneman, Daniel, “Attention and Effort,” Thinking, Fast and Slow, p. 33, Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2013. bit.ly/3Tzqucy.

4. Klein, Gary, Sources of Power: How People Make Decisions, The MIT Press, 1999.

5. “Live at FDIC,” Command Show, Fire Engineering Podcast, April 25, 2023. bit.ly/3vEtxIl.

REFERENCE

Click the QR code to see more important data from the Firefighter Rescue Survey.

ERIC LINNENBURGER is a battalion chief for the Westminster (CO) Fire Department, where he has been for 26 years. He spent 24 years in the ranks of firefighter, paramedic, lieutenant, captain, and currently battalion chief. Linnenburger has a bachelor’s degree in applied science, business of government, from Regis University Denver, and an associate degree in fire science technology from Aims Community College.