Photo by Tony Greco.

By Brian P. Kazmierzak

By now, we have all heard the rants or seen the social media posts about Underwriters Laboratories (UL) Firefighter Safety Research Institute (UL-FSRI) and National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) studies and how those groups are finally doing interior attack studies.

I find it funny that UL/NIST never said interior attack wasn’t good, but that there were other options that may work just as well and make the push a little safer for everyone, including the occupants. These other options are very important, for several reasons. First, there is no black or white in the fire service; we are the original “Fifty Shades of Grey!”

Second (and most importantly) is staffing. In April 2010, NIST, in conjunction with the International Association of Fire Fighters (IAFF) and the Center for Public Safety Excellence released the Report on Residential Fireground Field Experiments, a study comparing different levels of staffing with key fireground tasks. This study has been forgotten about, and that’s unfortunate because it’s probably one of the most important pieces of ALL the research that exists. Coupled with the modern fire behavior works of UL-FSRI and NIST, it makes all the pieces come together.

According to IAFF’s Lori Moore-Merrell of IAFF, a principal investigator on the study, “The four-person crews were able to complete search and rescue 30 percent faster than two-person crews and five percent faster than three-person crews.”

Five-person crews were faster than four-person crews in several key tasks. The benefits of five-person crews have also been documented by other researchers for fires in medium- and high-hazard structures such as high-rise buildings, commercial properties, factories, and warehouses.”

Crews of two, three, four, and five firefighters were timed as they performed 22 standard firefighting and rescue tasks to extinguish a live fire in the test facility. Those standard tasks included occupant search and rescue, time to put water on fire, and laddering and ventilation. Apparatus arrival time, the stagger between apparatus, and crew sizes were varied.

Researchers also performed simulations using NIST’s Fire Dynamic Simulator to examine how the interior conditions changed for trapped occupants and the firefighters if the fire develops more slowly or more rapidly than observed in the actual experiments. The fire modeling simulations demonstrated that two-person, late-arriving crews can face a fire that is twice the intensity of the fire faced by five-person, early arriving crews. Additionally, the modeling demonstrated that trapped occupants received less exposure to toxic combustion products, such as carbon monoxide and carbon dioxide, if the firefighters arrive earlier and involve three or more persons per crew.

Let’s take a look at three different types of fire departments and their staffing models.

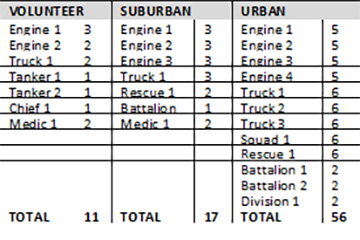

TABLE 1. Department Staffing Models

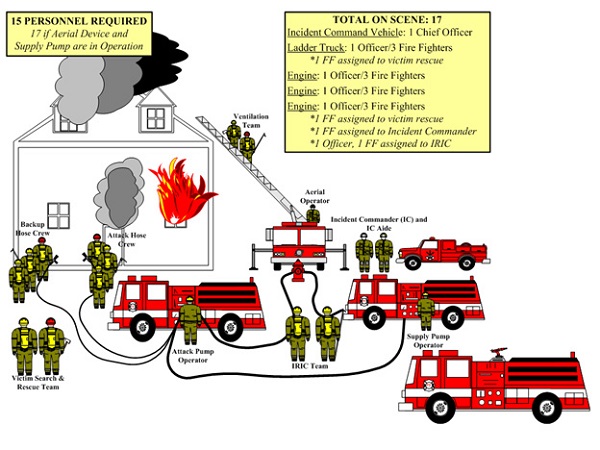

As you can see from Table 1, tactics cannot be the same for the volunteer department who is arriving with 11 or less members to a fire than a department that is getting 56 members on a working fire. There is a large difference in fireground tasks that happen sequentially instead of those that happen simultaneously. A department that shows up with 11 members only really has five members for fireground work after you take out the pump operator, incident commander (IC), emergency medical services stand-by crew, and two or more tanker drivers. So, that department may not be able to able to conduct coordinated fire attack, meaning that the engine is advancing at the same time as the truck while someone else is searching. With the urban staffing of 56 members, that department can put numerous members on a handline; team up two companies to advance a 2½-inch attack line; have companies on the floors above with hoselines; conduct searches under the protection of those hoselines; and have backup lines, a roof team or teams, an outside vent team, a firefighter assist and search team/rapid intervention team, and members throwing ladders and raising aerial devices, all while forming a command team that includes an IC, a safety officer, an accountability officer, a staging area manager, and a fire attack or an operations chief. All of these tasks are coordinated with one another and, in most cases, they happen simultaneously because of response times being well under eight minutes.

The lower the staffing, the less the likelihood of a coordinated fire attack. If it is not coordinated, we end up with no ventilation or, worse yet, uncoordinated ventilation, and then we get caught in the exhaust of the flow path, and so on.

NFPA 1710 Staffing Graphic. (www.IAFF266.com.)

So, the next time you read on social media someone trashing modern tactics, ask what type of department are they from? Is their staffing the same? If not, the tactics they employ will most likely not be the same as yours. However, your tactics can be similar to theirs with proper training and use of mutual-aid resources.

I wish I had the 56 members at every working incident, but for 99 percent of the fire service world, that is not a reality. Our tactics must be dictated by our staffing and our training, not just by a class we attend or something we’ve read. Remember, just because a tactic was developed in urban America doesn’t mean we have to use it. But, perhaps we can use it with some minor modifications (and vice versa) for tactics developed in rural America. Additionally, we must pay attention to ALL of the research being done by UL and NIST and realize that the research is more “tools in the toolbox” that we can apply to any fire department because there are no “always” and “never” in our job.

In the end, this isn’t about us; this is about “Mrs. Smith.” We are sworn to save lives and property, so whatever we can do to decrease temperatures, increase oxygen levels, and decrease fire gases, we should do it, no matter the tactic used. To quote the late, great Tom Brennan, “It comes down to tactics. I don’t want to do anything first. I want to do seven things all at once.”

Brian P. Kazmierzak, EFO, CTO is the division chief of training for the Penn Twp. Fire Dept. in Mishawaka, Indiana. He has a bachelor’s degree in fire service administration from Southern Illinois University and serves as the director of operations for www.FireFighterCloseCalls.com and the Webmaster for www.ModernFireBehavior.com. Brian was the recipient of the 2006 F.O.O.L.S. International Dana Hannon Instructor of the Year Award, the 2008 Indiana Fire Chiefs Training Officer of the Year Award Recipient, and the 2011 International Society of Fire Service Instructors (ISFSI)/Fire Engineering George D. Post Fire Instructor of the Year. In addition, Brian completed the National Fire Academy’s Executive Fire Officer Program in 2006. He is a CPSE credentialed Chief Training Officer, serves as a Director at Large for the ISFSI, and is on the UL FSRI PPV Research Study Panel.

Brian P. Kazmierzak, EFO, CTO is the division chief of training for the Penn Twp. Fire Dept. in Mishawaka, Indiana. He has a bachelor’s degree in fire service administration from Southern Illinois University and serves as the director of operations for www.FireFighterCloseCalls.com and the Webmaster for www.ModernFireBehavior.com. Brian was the recipient of the 2006 F.O.O.L.S. International Dana Hannon Instructor of the Year Award, the 2008 Indiana Fire Chiefs Training Officer of the Year Award Recipient, and the 2011 International Society of Fire Service Instructors (ISFSI)/Fire Engineering George D. Post Fire Instructor of the Year. In addition, Brian completed the National Fire Academy’s Executive Fire Officer Program in 2006. He is a CPSE credentialed Chief Training Officer, serves as a Director at Large for the ISFSI, and is on the UL FSRI PPV Research Study Panel.