BY KATIE VANDALE

There is no substitute for sleep. Like food, oxygen, and water, sleep is essential to maintain mental and physical well-being. In today’s society, emergency medical services (EMS) workers respond to emergencies 24 hours a day, seven days a week, and 365 days a year. EMS personnel are not immune to the physical, mental, and emotional consequences of sleep deprivation. Extended periods without sleep, disrupted sleep, and working against the body’s natural circadian rhythm can compromise the effectiveness of the EMS worker and impair performance, resulting not only in placing patient safety at risk but also in detrimental consequences to the EMS worker. Although we cannot avoid 24-hour operations, employers and employees can take measures to minimize the effects of sleep deprivation on EMS responders.

NORMAL SLEEP

We must sleep to maintain normal levels of cognitive skills such as speech, memory, critical thinking, and sense of time. To understand the effects of sleep deprivation and differing work hours on an individual’s health, you need to know what sleep is, what causes it, what its effects are, and why it is so important.

Sleep is a natural state of rest that fosters a restorative function in the physiological, neurological, and psychological states. It is characterized by reduced or absent consciousness, relatively suspended sensory activity, and inactivity of all voluntary muscles. Body systems are restored by sleep, which has positive effects on growth, healing, immune functions, and metabolic activities.

Contrary to common belief, sleep is actually an active, organized process. How and when we sleep is governed by several factors. Some factors we can control, such as whether or not we are sleep deprived, and some we cannot control, such as our internal biological clock. Our internal clock regulates our biological rhythm, also known as circadian rhythm. Located in the hypothalamus of the brain, this genetically programmed mechanism controls rhythms of alertness, body temperature, and hormone production over a 24-hour period.

STAGES OF SLEEP

Sleep occurs in stages, which take place at different times during the night and are divided into two categories: rapid eye movement (REM) sleep and nonrapid eye movement (NREM) sleep. NREM sleep occurs as sleep begins and is then further divided into four stages that indicate progressively deeper sleep.

Stage 1 is the transition between alertness and drowsiness. The brain and body become more relaxed. Body temperature drops, and breathing becomes more regular. Stage 1 is a very light sleep; the sleeper may be awakened easily or report that he was not sleeping. This stage is very brief, lasting only five to 10 minutes.

Stage 2 lasts approximately 20 minutes. Breathing pattern and heart rate begin to slow down. During this stage, a person loses consciousness. Senses such as hearing are reserved. Sleepers can still be aroused but not as easily as during the first stage of sleep.

Stages 3 and 4 are phases of deep sleep. During stage 3, the brain begins to produce deep, slow brain waves known as delta waves. Breathing and heart rate are at their lowest level; metabolic activity slows; and hormones responsible for growth, development, and tissue repair are secreted.

Stage 4 is the deepest phase of sleep, lasting approximately 30 minutes. During deep sleep, a person becomes very difficult to awaken. If aroused, he may still feel groggy and react slowly to physical and verbal stimuli. This period of sleep is the most restorative. The body is given the opportunity to cleanse, repair, and rejuvenate itself.

Finally, sleep moves into the REM phase. During this final phase, one becomes temporarily paralyzed with the exception of the eyes. Breathing and heart rate increase and become more irregular. Blood pressure fluctuates. The eyes dart back and forth, hence the name “rapid eye movement.” During REM sleep, memories and thoughts from the day are processed, and most dreaming occurs.

Each sleep cycle lasts approximately 90 minutes and may repeat four or five times a night, but the normal sleep cycle sequence will not be followed if REM sleep is interrupted. A person’s level of alertness depends on which stage of sleep he was in when awakened. In stages 1 and 2, the person may feel more awake and refreshed than if aroused during stage 3 or 4, when the person experiences a state of confusion and reacts more slowly to physical or verbal stimuli.

SLEEP DEPRIVATION AND LONG WORK HOURS

Sleep deprivation occurs when a person fails to get sufficient quality sleep or experiences a circadian rhythm disturbance. If a person gets less sleep than the brain requires, that person is, by definition, sleep deprived. There is, in fact, a wide range of sleep time that is considered “normal.” The average person gets approximately 7.5 hours of sleep each night, but some people do very well with as little as five hours of sleep. At least four to five hours of uninterrupted sleep are necessary to maintain minimum performance levels.

SHIFT WORK

In today’s society, sleep is frequently regarded as a luxury instead of a necessity. Demanding work schedules and shift work are the new normals in our 24-hour society. Shift work involves working outside the typical “9 to 5” business day. Our 24-hour society requires important services be provided at all times. Critical services include public safety such as police, fire, and EMS providers; military defense; transportation; and public utilities such as electrical power, water, and telephone.1 EMS providers work a variety of shifts to provide continuous 24-hour services to their community. The nature of EMS shift work includes overnight duty, rotating schedules, early awakening, and interrupted nocturnal sleep.

EMS workers are constantly faced with difficult clinical cases and workloads that are taxing physically, mentally, and emotionally. For example, EMS workers are regularly required to problem solve delicate and sometimes complex issues in an independent self-governing and timely fashion. They are required to perform clinical skills; administer drugs; and drive with professionalism, skill, and care. Their management is crucial during treatment of critical patients, where skills are paramount and errors in judgment or lapses in concentration can lead to fatal consequences.

Violent patients pose another challenge to EMS workers. These patients can be under the influence of drugs or alcohol or are living with mental health issues and must be approached with caution. Furthermore, EMS workers are faced with the palliative and terminally ill as well as the emotions of the patient, family, and friends as these individuals face their mortality. In addition to dealing with violent and delicate situations, EMS workers are also exposed to illness and disease, which can affect their health and the well-being of their families.

THE EFFECTS OF SLEEP DEPRIVATION

In general, long work hours and chronic sleep loss have been associated with adverse health consequences. It is recommended that healthy adults who do not have demands limiting their sleep receive eight hours of sleep per night. Mortality increases in men and women when they deviate from that amount.

Some of the most serious problems shift workers face are frequent disturbances in sleep and sleepiness. Sleep deprivation produces impairments in the central nervous system (CNS) that can result in drowsiness, fatigue, decreased alertness, slowed reaction time, and impaired thinking and judgment; these effects can lead to accidents, errors, injuries, and fatalities. In fact, studies have shown that being awake for 18 hours produces impairment equal to a blood alcohol concentration (BAC) of 0.05 percent and reaches a BAC equivalent of 0.10 percent after 24 hours of wakefulness. Thus, a drowsy driver may be just as dangerous as a drunk driver.2

Motor vehicle crashes have a clear relationship to fatigue and other types of driver impairments; the greatest number of studies relate long work hours to an adverse impact on safety. In the United States, the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA) estimated that in 2000, drowsy driving was responsible for 100,000 police-reported crashes and 40,000 injuries annually. (2)

Ambulance crashes are among many hazards faced by EMS personnel. Although no complete national count of ground ambulance crashes exists, the total number of fatal crashes involving ambulances can be determined by using the NHTSA Fatality Analysis Reporting System (FARS). The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC) National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) and NHTSA investigated three case reports of ambulance crashes.3 With already fatigued EMS personnel, these hazards can only increase with sleep-deprived personnel.

One tragic fatigue-related death of an EMS worker was highly publicized. Brian Gould, a 42-year-old paramedic, died while driving home from an overnight shift. Drugs, alcohol, and weather were determined not to be factors. Because of the incident, the ambulance service implemented a policy that if a crew member got less than four hours of uninterrupted sleep during a 24-hour shift, colleagues are to take the member and his vehicle home after work.4

THE HEALTH EFFECTS OF SLEEP DEPRIVATION

Sleep deprivation also has serious short- and long-term health impacts. Chronic sleep loss can also lead to mental health issues including depression. Mood is also often affected with increases in headaches, irritability, anxiety, and depression. These symptoms can have devastating effects on domestic and social relationships. Shift workers often miss out on social and sporting events and family gatherings when they need to work or sleep instead. These demands can lead to feelings of frustration, isolation, and depression, as valuable family and personal time is lost.

Sleep is essential to the cognitive function of the brain; without it, our ability to consolidate memories, learn daily tasks, and make decisions is largely impaired. REM sleep helps solidify memories the brain creates throughout the day so that they can be easily organized and stored in the mind’s long-term reserve.

According to the CDC, about 65 percent of Americans are overweight or obese. The number of obese adults jumped from 15 percent in 1980 to 27 percent in 1999. Evidence is linking sleep loss with obesity. During sleep, our body releases specific hormones and chemicals that control appetite and manage weight gain. Research has show that people who sleep less than seven hours per night were more likely to gain weight and become obese than those with longer sleep durations.5

Prolonged sleep deprivation has been associated with diminished immune functions. The blood levels of specialized immune cells and important proteins called “cytokines” are altered when the body gets less than six hours of sleep a night, reducing immune response. A sleep-deprived person may catch the common cold more frequently than a well-rested person.

Most adults require six to eight hours of sleep each day, but if an individual’s circadian rhythm is disrupted, it can have lasting effects. Long work hours and chronic sleep loss result in the decreased ability to think clearly and handle complex tasks and can cause depression. Long work hours and chronic sleep deprivation have also been linked to a general increase in health risks that can include diabetes, sleep apnea, and a heightened risk for cardiovascular disease. Adequate daily sleep is essential to perform optimally and remain healthy.

EMS RESPONDERS AND SLEEP DEPRIVATION

In today’s society, prehospital providers work a variety of shifts to provide continuous 24-hour services to their communities. EMS workers are constantly and increasingly faced with heavy workloads that are physically, mentally, and emotionally tiring.

Unlike the fire service, which has produced several large studies and numerous other smaller studies linking fatigue and sleep deprivation to shift scheduling and structure, EMS has not been adequately researched. EMS workers’ shift schedules and structures vary widely, based on the size of the agency and call volume. Shift lengths include 8s, 10s, 12s, 14s, 16s, and 24s, all of which are in use somewhere across the nation and even internationally. In general, the total hours worked per week in an EMS agency averages approximately 54 hours but often reaches higher totals. (2)

There have been articles published recently in fire service magazines on the controversial issue of 24-hour shifts in the fire and EMS industries. It’s not the 24-hour shift, per se, that is the problem so long as employees can get five consecutive hours of uninterrupted sleep within that 24-hour period. In lower-call volume areas, they may get only one or two calls in a 24-hour period, making 24-hour shifts reasonable. However, the 24-hour shift may not work so well for agencies with a higher call volume.

DEVELOPING AN EFFECTIVE SHIFT SCHEDULE

Review key issues and questions to determine what will work best for your agency when developing a shift schedule. Consider schedule pattern and the impact of the circadian rhythms, employees’ ages, and how rested employees are at the beginning of their shifts. As previously mentioned, the circadian rhythm is part of the biological function within the brain that varies over a 24-hour period. To maintain a consistent sleep/wake pattern, dramatic changes in schedule patterns on a routine basis are not advised.6

As we age, changes to our sleep patterns are a part of the normal aging process. As we grow older, it becomes more difficult to fall asleep and stay asleep. The normal circadian pattern of sleep gradually weakens, and sleep tends to be spread across the 24-hour day rather than being consolidated in the night-time sleep period. All of these changes result in a common complaint of the aging population: Sleep becomes shorter and less restorative. As EMS workers become older, their bodies do not respond as quickly to schedule and circadian rhythm changes.

In today’s economy, most EMS workers report having one full-time job and other part-time jobs just to make ends meet. Ensuring that the EMS worker is well-rested before a shift should also be a fundamental requirement of the agency. (6)

EMS work alone is stressful; poorly developed scheduling practices can add to this stress. There are four types of anxiety typically associated with employment.

- Time stress is the anxiety associated with completing a task before a deadline. It is also a feeling of not having enough time in the day to finish everything.

- Anticipatory stress is the stress of an impending event-state inspections, recertification exams, and interviews, for example.

- Situational stress is associated with being near or around a particular person, place, or thing. Mass-casualty incidents are a prime example-you need to complete many different tasks in a short time. Situational stress can also be caused by entering an unsafe scene or dealing with a violent patient. In EMS, we are faced with this stressor more than any other.

- Encounter stress relates to dealing with a person or people you find unpleasant. Sometimes, too much interaction with a particular person, such as a co-worker, without adequate time off can cause this type of stress.

There are a few ways to reduce the impact of stress in an EMS system. Make sure the workload is reasonable. Monitor and adjust the workload as needed to spread the workload evenly among crew members within the agency so as to not burn out the workers. Also consider an individual’s physical comfort during a long shift-for example, cloth seats, tinted windows, air-conditioners, and CD players within the ambulance should be considered to ensure the crew’s comfort. These are just a few examples of job-loading factors that can reduce the stress level of EMS workers. (6)

One of the largest costs to a business is labor. You want to cover the company’s needs while avoiding unnecessary payroll obligations and not burning out your employees. In developing a work schedule, it is important to consider your needs as well as employee flexibility. When creating an effective work schedule, consider the following: shift length, daily rotation, and total hours per week.

The question may arise whether the schedule will meet the expectations of the patients. Patients deserve fresh, rested, competent, and polite EMTs and paramedics in their time of need. Does the work schedule complement or antagonize an individual’s biological clock? Would your patients be surprised to find out how many calls and hours their caregiver has worked without adequate rest? Recently, more and more attention is being drawn to the 24-hour shift and the need to shorten it to ensure caregiver alertness and safety.7

The next step in developing a shift schedule is getting the people to want to work these particular shifts. Not all employees have the same needs or desires for shift work. Some prefer longer shifts so they can have more days off for personal use; others may prefer short shifts.

A recent JEMS article included a case study out of the District of Columbia Fire and EMS (DC FEMS). Fire Chief Kenneth Ellerbe, appointed in 2011, planned to replace the existing 24-hour shifts with a series of 12-hour shifts. His efforts in changing the shift schedule are being met with strong opposition. It was reported that more than 100 DC FEMS employees walked out on Ellerbe at the end of his “state of the department” speech. The demonstration was an unmistakable criticism of the chief’s attempt to make changes to the schedule. Ellerbe states that his reasoning behind the change is to meet safety concerns being raised during the second half of the 24-hour shift. He also stated that it would be more cost effective.

Employees of the DC FEMS feel that, although it may be cost effective, it is a disruption to the employees’ lifestyle. Another issue is that a certain number of the members have significant commutes. The employees say that their current schedule of 24 hours on, 72 hours off allows them to work fewer days, making the longer commute more tolerable and affordable. News sources report that the morale of the department is seriously suffering.8

Finally, as in any business, budget realities are a major factor. Work schedules need to provide high-quality emergency care while simultaneously making the schedules cost effective.

Review these questions and issues while considering the patient and organizational goals. EMS agencies need to blend work schedules, caregiver needs, payroll budgets, and other related expenses while developing an effective and efficient work schedule.

No matter what sort of schedule the department comes up with to minimize sleep deprivation, sleep loss will always be present. There is no perfect shift schedule. Different organizations require different work systems, and there are advantages and drawbacks to each type of schedule.

MANAGING WORK HOURS

One in five U.S. workers work evenings, nights, rotating shifts, or other irregular shifts. It is estimated that fatigue costs U.S. employers close to $137 billion annually in health-related costs and lost worker productivity. (2)

Chronic sleep deprivation may not be recognized, and it is important for firefighters and EMS personnel to acknowledge their need for and to maximize their ability to achieve adequate sleep. Despite warnings from health and legal experts, more than likely the 24-hour shift will be around long after we are gone. Those who work long-duration shifts can improve their well-being by leading a healthy lifestyle. Firefighters, EMS personnel, their families, and management need to work together to meet the needs of professional excellence and the well-being of the employee.

SLEEP HABITS

For shift workers, sleep health habits are a primary issue. How do you control them? Take responsibility for getting enough sleep to feel rested and restored. Adverse effects of sleep deprivation and long work hours are minimized when people establish some regularity in their sleep/wake cycle. A regular sleep time and wake time will strengthen the circadian function.

Create a sleep-conducive environment. Design your sleep environment to establish good sleep conditions. Remove the TV, the radio, or anything else that can distract you from sleeping. People sleep better in cooler, darker rooms. Make sure your mattress is comfortable, and change the sheets often; cleanliness always promotes a pleasant environment.

Avoid heavy foods and alcohol before bed. Eating or drinking too much may make you less comfortable when trying to sleep. Avoid caffeine, as it is a stimulant and can produce an alerting effect.

EXERCISE

In general, keeping physically fit helps resist stress and illness. Regular exercise keeps a person from becoming tired too quickly. For shift workers, the timing of exercise is important in that it should not make a person too tired to work. Try to avoid exercising at least three hours before sleep so that you give your body enough time to cool down. On the other hand, moderate physical activity will increase alertness, and exercise during a night or long shift can reduce feelings of fatigue. Providing exercise equipment such as bicycles or ping-pong tables may make exercise more enjoyable and realistic for employees.

DIET

Diet, along with exercise, helps you to stay physically fit. This means avoid fatty and sugary foods, which will cause you to gain too much weight. Avoid heavy or fatty foods, especially in the middle of the night because they are difficult to digest at the time.

NAPPING

Although naps do not make up for inadequate or poor quality nighttime sleep, a short nap of 20 to 30 minutes can improve mood, alertness, and performance. (2) Naps longer than 45 minutes can result in awakening during the deeper stages of sleep and create greater feelings of grogginess and disorientation.

Shift work is difficult and isn’t for everyone. These workers frequently suffer from several health problems but can improve their well-being by leading a more healthful lifestyle.

The 24-hour work shifts have remained in effect for many years because of their historical value. Many employees find these shifts desirable, and few are willing to sacrifice the benefits they provide. But the time has come to reevaluate the 24-hour schedule. More and more studies and articles are surfacing with information that this schedule is taking a toll on the human body, which is not designed to operate around the clock. Fatigue and sleep disturbances can compromise the effectiveness of emergency workers and their performance, putting at risk not only the patient but also the emergency worker’s health and well-being. It is crucial that these workers obtain restful breaks and restorative sleep so they can maintain a professional, reliable, and consistent approach to their jobs and preserve their well-being. Whether or not alternative schedules are implemented, employees and employers need to be educated on the effects of sleep deprivation and shift work and ways to cope with their effects.

KATIE VANDALE has been a paramedic/field supervisor for the Bennington (VT) Rescue Squad since 2007. She began her career as a volunteer EMT in 2002. She is also a volunteer firefighter with the Pownal Fire Protective Association. She has a bachelor of science degree in emergency medical services management from Springfield (MA) College and received her paramedic training at Hudson Valley Community College. She is the coordinator for Bennington Rescue Squad’s annual townwide Health and Safety Fair and also teaches CPR for the HeartSAFE community program.

References

1. Rosa RR, Colligan MJ. Plain Language About Shift Work. DHHS (NIOSH) Publication No. 97-145.

2. Elliot DL, Kuehl KS. Effects of Sleep Deprivation on Firefighters and EMS Responders. Final Report, 2007. Retrieved February 1, 2012. www.iafc.org/sleep.

3. CDC. Ambulance Crash-Related Injuries Among Emergency Medical Services Workers–United States, 1991-2002. February 28, 2003/52(08);154-156. Retrieved March 26, 2012. http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm5208a3.htm.

4. “Erich J. Brian saved futures’: medic’s crash spurs new fatigue policy at neighboring agency.” Retrieved March 26, 2012. www.emsresponder.com/publication/article.jsp?publd=1&id=4676.

5. National Sleep Foundation. Obesity and Sleep. Retrieved April 12, 2012. http://www.sleepfoundation.org/article/sleep-topics/obesity-and-sleep.

6. Fitch J, PhD. Prehospital Care Administration, Second Addition. 2004.

7. Rand A. Prehospital Care Administration, Second Addition. 2004.

8. McCallion T, “Consider the Dangers of Shift Work.” Retrieved April 20, 2012. www.jems.com/article/emsinsider/consider-dangers-shift-work.

Additional References

1. BBC. The Science of Sleep. Retrieved April 12, 2012. http://www.bbc.co.uk/science/humanbody/sleep/articles/whatissleep.shtml.

2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. “26-year-old emergency medical technician dies in multiple-fatality ambulance crash-Kentucky.” Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, CDC, 2001; DHHS (NIOSH) publication no. FACE-2001-11.

3. Kahn CA, Pirrallo RG, Kuhn EM. “Characteristics of fatal ambulance crashes in the United States: an 11-year retrospective analysis.” Prehosp Emerg Care 2001;5:261–9.

4. Lovell K, PhD, Liszewski C, MD. “Normal Sleep Patterns.” Retrieved March 26, 2012. http://learn.chm.msu.edu/NeuroEd/neurobiology_disease/content/otheresources/sleepdisorders.pdf.

5. Maguire BJ, Hunting KL, Smith GS, Levick NR. “Fatalities in emergency medical services: a hidden crisis.” Ann Emerg Med 2002;40:625–32.

6. National Sleep Foundation. Healthy Sleep Tips. Retrieved April 12, 2012. http://www.sleepfoundation.org/article/sleep-topics/healthy-sleep-tips.

7. National Sleep Foundation. Shift Work and Sleep. Retrieved April 12, 2012. http://www.sleepfoundation.org/article/sleep-topics/shift-work-and-sleep.

8. National Sleep Foundation. Sleep Drive and Your Body Clock. Retrieved April 12, 2012. http://www.sleepfoundation.org/article/sleep-topics/sleep-drive-and-your-body-clock.

9. Patterson DP, PhD, MPH; Suffoletto BP, MD; Kupas DF, MD; Weaver MD, NREMT-P; Hostler D, PhD. “Sleep Quality and Fatigue Among Prehospital Providers.” Prehospital Emergeny Care, April/June 2010, Volume 14/ Number 2. Retrieved April 12, 2012. http://www.paems.org/pdfs/online-ce/sleep-quality.pdf.

Firefighter Sleep Deprivation in the Raleigh (NC) Fire Department: An Objective Test

BY BRAD HARVEY

Sleep specialists do not consider firefighters’ unique schedule typical shift work; they refer to it as “on call” shift work, where normal sleep is more difficult. The total amount of sleep for firefighters “on call” is reduced because it takes them longer to fall asleep in view of the fact that it is likely that their tranquility and peace will be threatened by an emergency. Some workers often insist on going to bed later than usual because they prefer that to being startled shortly after drifting off.

“On call” sleep does not have as much positive impact as normal sleep in that it lacks deep sleep and rapid eye movement (REM) sleep. In general, the anticipation of being called out on an emergency prevents firefighters from getting restful sleep.

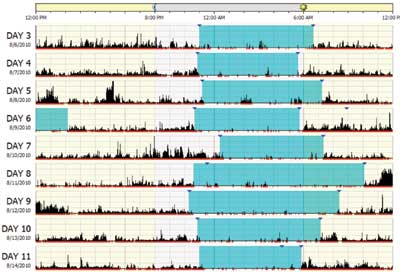

| Figure 1. Individual Actigraphy Sample |

|

An objective measure of how much people are sleeping is obtained through their wearing a device called an “actigraphy.” We conducted original human research among our department personnel with the assistance of Dr. David Dickinson of Appalachian State University and approval of the school’s Institutional Review Board.

Actigraphy watches are similar to wrist watches and are designed to be worn mostly 24 hours a day and measure wrist movements represented similar to seismographic earthquake data. Ideally, they should be worn 24/7, but they can be removed during extreme activities such as swimming for extended periods.

Our firefighters were instructed to wear the watches under their protective gear during emergency calls; however, if they felt endangered by it, they were to remove it immediately. The firefighters pressed the event button only when the subject attempted to fall asleep, woke up, removed the watch, or replaced the watch after the initial start-up day. This button did not stop or start recording data; it marked a significant event that accompanied the subject’s sleep diary. The sleep diaries were filled out daily before bed and immediately after waking up. A few examples of the information collected include the following: the number of caffeinated drinks consumed; the number of alcoholic drinks consumed; and the time the subjects first attempted to go to sleep. After the two-week research period, all watches were shipped back to Dr. Dickinson, and the data were downloaded and analyzed. Figure 1 shows a sample of the data.

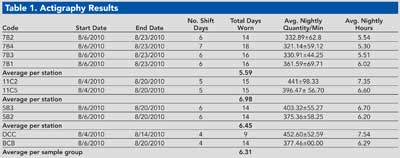

The first column “code” represents the subject’s “name-code” assigned to protect identity. “Average nightly sleep quantity” represents sleep quantities with a standard deviation indicating variation in sleep quantities across different nights. For example, subject “11C5 average nightly sleep quantity = 396.47 ± 56.70 minutes” consisted of sleeping between 340 and 452 minutes per night. The entire sample group averaged 6.31 hours of sleep a night and had a sleep efficiency of 85.17 percent.

Figure 1 is an example of the data collected from a subject’s actigraphy watch during the study. Shaded areas represent attempted “sleep periods.” These data were analyzed with the subject’s sleep diary in an effort to validate the activity on the graph. This subject was “on call” August 6, 8, and 10. Note the activity on Day 5 during the hours of 2:00 a.m. and 5:00 a.m., representing possible calls of approximately 45 minutes each.

The actigraphy data illustrate that the nocturnal sleep on August 8 was interrupted twice for a total of about 130 minutes and that on August 9 the subject napped for approximately two hours without disturbing his “sleep efficiency” the following night, for a total nine hours of sleep time for that day.

Data from our department’s research validate recommendations made by some sleep experts that crews be rotated so they do not work in busy stations for extended periods and that work schedules be revised every seven years. (Lorber, J. 2010). Personnel from St. #5 (1,306 incidents a year) averaged 6.45 hours of sleep a night, and subjects from St. #7 (1,771 incidents a year) averaged 5.59 hours a night. Discretion is needed when interpreting these data relative to differing personal habits since subjects were off duty as much as they were on duty while sleep habits were monitored.

Research has shown 78 percent of our firefighters felt they received less than seven hours of sleep a night. This information was confirmed through the actigraphy data, which confirmed that two out of 10 subjects accumulated at least seven hours of nocturnal sleep. Dr. Dickinson indicated the following in a phone interview on August, 25, 2010: “Preliminary results of the study indicated the average subject received just over six hours a night, whereas the normal healthy adult should average eight hours a night.”

Subjective surveys and objective research from this project confirmed the sample group averaged 6.31 hours a night over the two-week research period. This project involved a small sample group because of the limited number of measuring devices, and it included the sleep for “days on” and “days off” for the entire group.

BRAD HARVEY is a 23-year veteran of the Raleigh (NC) Fire Department, where he is assistant chief-training. He is a recent graduate of the National Fire Academy’s Executive Fire Officer Program.