BY FRANK RICCI AND SAM VILLANI III

An emergency incident’s initial moments can make or break the operation. Understandably, the quality of decisions made in a split second have inherent limitations. Such decisions must be almost perfect, even though they are often based on imperfect or missing information. It is critical to develop a measurable way to improve our size-up so we can practice and evaluate it on and off the fireground.

The first radio reports and the scene size-up are two key opportunities for the company officer and the first-arriving command officer to set the stage for the entire operation. We must ensure that we do not overlook key elements that could lead to improper tactical decisions. It is well supported that improper scene size-up can lead to injury or death.

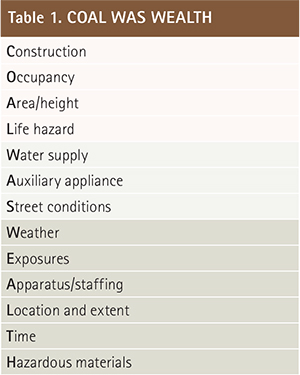

Most new firefighters and officers are taught the New York City 13-point scene size-up acronym COAL WAS WEALTH (Table 1), made famous by Deputy Assistant Chief (Ret.) John Norman of the Fire Department of New York and widely accepted as the standard size-up. Over the years, it was slightly modified to address particular areas or department needs. However, practical application of this scene size-up is often problematic for new officers and firefighters

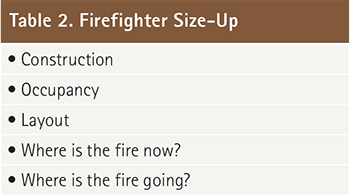

When new firefighters have been assigned to my [Ricci] shift over the past 17 years, at structure fires I ask them to tell me their scene size-up while inside. The lack of detail conveyed is astounding. I have shared this at classes and at the Fire Department Instructors Conference (FDIC) International, finding other firefighters reporting the same results. The new firefighters and some seasoned firefighters could state the general type of building, how many windows had fire or heavy smoke coming out, but little else. This is why Anthony Avillo and I added a section on scene size-up for recruit firefighters in Fire Engineering’s Handbook for Firefighter I and II. The new firefighter needs to cover at least five points as a foundation (Table 2). As training, education, and experience increase, firefighters will include more and more of the 13 scene size-up items.

Through listening to radio reports and reviewing National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health reports, we found that not only are rookie firefighters missing critical scene size-up components but also that some officers are missing what is right in front of them. Why?

Why? Training!

Except for teaching our members to stay calm, the fire service has done a disservice to our members. In critiques, we have blamed the individual without any reflection on how the individual was trained. Professor Morris Kline in 1958 called on teachers to stop blaming students for poor mathematic skills and instead focus on the instructors, the curricula, and the texts. This principle is applicable to us, with the addition of physiology. When there is a failure on the fireground, one of the contributing factors is likely the quality of the training.

Physiology

Understanding how our mind and body work is imperative to reading a building during scene size-up. We have identified several mitigating factors that combine in synergistic ways to make our initial assessments more difficult. Our own physiology works against us and impairs our focus on digesting all the information we need. However, with a little understanding and practice, we can minimize the effects of preconditioned responses to our environment.

First, your eyes will automatically focus on the brightest object in your field of vision. This will usually cause your pupils to dilate. In itself, this explains why the new firefighters were all able to convey how many windows had fire coming out of them. Think about it-if you’re in a dark room and a crack of light enters, you will immediately focus on that area.

Next, we look at our instincts as humans and the historical threats we have faced. There was a time when we were prey for other animals and prone to attack from other adversarial threats. Because of this history, our eyes will focus not only on the brightest object but also automatically on movement. Therefore, the new firefighters and officers consistently know the number of windows from which the smoke and fire are coming. Think about walking on a deserted city street or in the woods. As soon as something moves, what action do you take? History tells us you immediately turn your attention toward the perceived threat.

Adrenaline and the body’s fight-or-flight response also factor in. Think how you feel when an alarm comes in and your company responds to a routine activated alarm. Then consider how you feel when a box comes in for a working fire with a report of multiple calls and people trapped. There clearly is a difference, but do you understand why?

When we are stressed, the body releases stress hormones into the bloodstream. This release will dilate the pupils, increase respirations, elevate blood pressure, and provide more oxygen to major muscle groups. This reaction usually lasts for a few minutes, which is just enough time to affect your scene size-up. The most detrimental reactions are the elevation in heart rate and respirations and the dilation of the pupils. These three sensory responses contribute to diminishing perceptions, which result in a narrowing of peripheral vision.

This reaction has been well understood in police shootings and witness testimony. I [Ricci] recently had a gun pulled on me at work by an acting battalion chief. When the police interviewed me, I could easily convey what kind of gun it was and what the barrel looked like. What I could not recall was with which hand the firearm was drawn. However, he was right in front of me. I clearly saw the hand that drew the gun; however, my mind did not process it. My body’s reaction caused this tunnel vision.

Inattentive blindness occurs when the observer is overly focused on what he is looking at or for-for example, watching a football game on TV and failing to hear your spouse trying to communicate with you. This phenomenon can also cause you to miss something that is right in front of you.

During two popular experiments, observers were asked to count and focus on the task at hand. The viewers in both experiments missed the obvious distraction approximately 50 percent of the time. In Professor Daniel J. Simons’ work, he had a gorilla walk into the middle of one scene and had cheerleaders change clothes in another. Rezso Balint stated in 1907 (as translated in a 1988 article by Husain and Stein), “It is a well-known phenomenon that we do not notice anything happening in our surroundings while being absorbed in the inspection of something; focusing our attention on a certain object may happen to such an extent that we cannot perceive other objects placed in the peripheral parts of our visual field.” Through conversations with Professor Simons, we learned there are workable strategies to increase the chance of limiting inattentive blindness.

Minimizing Physiology’s Impact

Working in any complex and dynamic system demands attention to detail. Missing the obscure and the obvious can end with catastrophic results. That is why you will find checklists to standardize workflow processes for surgeons and pilots. In Atul Gawande’s book, The Checklist Manifesto, he demonstrated that with a well-designed checklist outcomes improve. This checklist does not have to be written; however, it must be practiced! Checklists enable the observer to shift focus, minimizing the chance of becoming overly fixated on one thing.

You just can’t learn the 13-point size-up and hit every item based on a general impression. To ensure each component is covered, ask yourself a question for each point or verbalize your scene size-up over the radio, which ensures that you will move your focus to another item.

Scene size-ups and initial radio reports are not just relaying information to incoming companies. These reports are also a checklist for the officer relaying the information. Using a checklist moves your focus, aiding in understanding and helping to minimize your own physiology, which is working against you. When an item is mentioned in the report, it is less likely to be missed.

Priming Your Mind

I [Villani] note the following. “As a public school teacher, I attended night graduate school to obtain my teaching credentials. In one of my early childhood development classes, we learned about the value of priming your mind. Priming the mind works its magic, at least initially, in reading the instructor manual prior to a lesson, attending that lesson, and then going out onto the training grounds and practicing the skills learned in that lesson. We need to follow these same steps in training for scene size-up.”

As company officers, we prime ourselves for tactical decisions based on the prevailing circumstances. Conversely, most department standard operating procedures (SOPs) call for us to communicate our actions over the radio in our initial, on-scene report. But who is this report for? In classes and conversations at FDIC International, many participants indicate that the initial radio report is for the other incoming companies. They often miss the initial radio report’s value to the officer making the report.

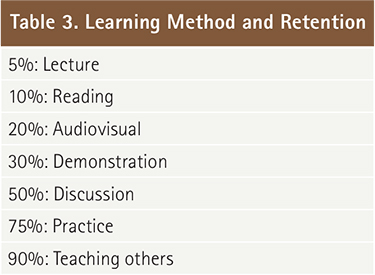

Understanding how we learn also plays a role. Dr. William Glasser developed the “choice or control theory,” which revolves around the four components of total behavior: acting, thinking, feeling, and physiology. You can see the relevance of Glasser’s theory in how we process information in the learning pyramid in Table 3.

Notice the synergy of what we see and hear and how much of that goes directly into what we discuss with others or, as a chief, what we might say over the air to incoming units. Vocally relaying your scene size-up over the radio minimizes the chance of your missing a critical factor that could lead to injury or death.

Radio Reports

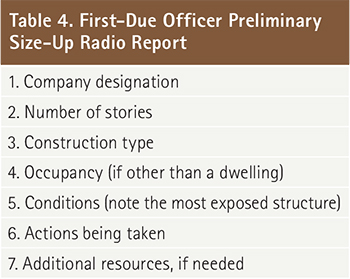

Radio reports are the signature of your department and directly reflect on the professionalism of the officer transmitting the report, the training division, and the department’s leadership. Initial reports set the stage for the entire incident. They are the first building block in the act of communicating your size-up through fire department radios. These reports should be standardized. Company officers in our cities are directed to hit only six to seven factors in their size-up (Table 4).

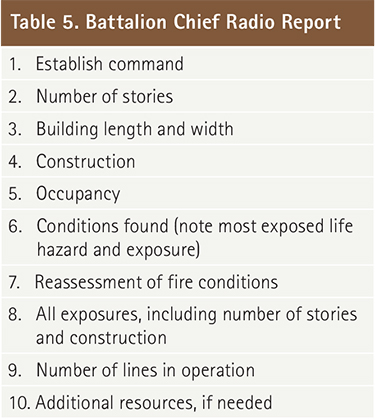

Note it is easy to recall seven factors. That is why phone numbers are limited to seven digits. Meanwhile, battalion chiefs are directed to cover more extensive factors (Table 5). It is an ever-evolving process that challenges even the veteran officers. Plainspeak has also added further complications with conveying our intentions into a short, understandable transmission. Plain language should be standardized when possible. For example, a 2½-story balloon- frame structure should not be described six different ways. This will only serve to break down communications.

Particular Relevance

Standardization also increases the particular relevance of what is being transmitted. Psychologists refer to this as the “cocktail effect.” We have all experienced “particular relevance” when, in a crowd talking to friends and out of nowhere, we hear our name spoken in another conversation within the same room. Or perhaps you have experienced it visually: You pick up on something that holds meaning to you, like picking out your child in a crowd or not hearing a radio report until your company designation is called. Standardization trains the listener and uses the effects of particular relevance to our best advantage.

These reports should sound the same regardless of which officer is giving the report. This continuity has a calming effect and should breed better understanding. We take audible and visual cues from what we see in our map books, what we see on our mobile data computers, and as we arrive at the incident scene. We have to filter this abundance of information. The only way to improve our reports is through repetition and standardization.

Most of us were taught in grade school that “practice makes perfect.” In the fire service, we use this to justify company drills and to reinforce the importance of studying maps and preparing for promotion. As company officers, we can use simulation software on platforms as small as a smartphone to practice radio discipline and incident management. Some of the latest simulation software allows you to insert photographs of target hazards and buildings in your response area, including interior views, which enables a company officer to practice responding, arriving, giving radio reports, and operating at emergency incidents (photo 1).

|

| Simulation courtesy of SimsUshare. |

With a computer and a projector, you can use these incident scenarios to involve and train multiple units and chief officers, providing the total incident experience. This is a quantum leap from generic building photographs and chalkboards! We have seen firsthand that using radios to convey what the officer sees on the screen will translate to more effective scene size-up on the street.

Tactical Saturation

Training is important, but it is not enough! The officer must be willing to place the knowledge into practice. One last issue that hinders good scene size-up and that has nothing to do with learning or our physiology is overinvolvement in the tactics at hand. Officers cannot get oversaturated in any single tactical task. Remember, your first role is supervising; don’t lose perspective because you still want to be the nozzle person or the outside vent person. If you don’t have the self-control to realize that your role and level of responsibility have increased, you have no business going for a promotion. The officer’s primary tools are not hand tools; they are his mind and his eyes.

America’s First Drillmaster

Baron de Steuben summed up the difference between European and American troops in one word: “Why.” The European teaching model of command-and-follow did not work well with the American militia. The American spirit dictated that the instructor explain the how and why for each lesson. With this information, the individual soldier would better understand the maneuvers, which would create a more effective fighting unit.

It is imperative that we do not lose this lesson from the past. As lifetime learners, we must continue to ask how and why. This simple action and our understanding of our limitations will aid us in moving toward more predictable outcomes.

ENDNOTES

Guwande, Atul. (2011) The Checklist Manifesto: How to Get Things Right. Metropolitan Books, Henry Holt and Company.

Husain, M., Stein, J. (1988) Rezso Balint and his most celebrated case. Archives of Neurology, 45, 89-93.

Simons, Daniel J., Chabris, Christopher F. (1999) “Gorillas in our midst: Sustained inattentional blindness for dynamic events.” Perception, 28, 1059-1074.

FRANK RICCI is a captain and the drillmaster for the New Haven (CT) Fire Department. He is an advisory board member for Fire Engineering and FDIC International. Ricci is the co-host of the radio show “Politics and Tactics” and has authored several Fire Engineering DVDs including Firefighter Survival Techniques and the Tactical Perspectives series “Command, Ventilation, Search, Fire Attack, and Mayday.” He is a contributing author to Fire Engineering’s Handbook for Firefighter I & II.

SAM VILLANI III, a 22-year fire service veteran, is a lieutenant with the Montgomery County (MD) Fire and Rescue Service and is assigned to Four Corners Engine and Truck 16. He has an associate degree in public fire protection from Montgomery College and a bachelor’s degree in sociology from the University of Maryland. He instructs the Montgomery County Public Safety Training Academy and for Capitol Fire Training. He is a Maryland certified level II instructor.

Reading A Building – Practicing The Theory

Reading A Building – Practicing The Theory, Part 2

Reading a Building : Construction Size-Up