Strategically, a fire department’s first priority is protecting civilian lives. Tactically, firefighters can remove the occupants from harm (rescue them from the fire building), remove the harm from the occupants (extinguish the fire), or isolate the occupants from harm (close doors and, in the case of multiple dwellings, shelter in place or relocate occupants to another area of the building). Let’s consider these options and when and how to apply them.

Closed Doors Save Lives

Research and fire experience have demonstrated that a common household hollow-core door can be a lifesaver. Underwriters Laboratories (UL) has found that rooms with closed doors had average temperatures of less than 100ºF and 100 parts per million (ppm) of carbon monoxide (CO); oxygen levels seldom dropped below a survivable 18 percent in rooms with closed doors vs. more than 1,000ºF and more than 10,000 ppm of CO in rooms with open doors.

RELATED FIREFIGHTER TRAINING

Avillo: Shut the Door! Tips for VES, VEIS (or VESS)

Caught in the Flow Path: Fighting a Basement Fire on the Fourth Floor

Realistic Vent-Enter-Search Training

Are You Ready to Perform Vent-Enter-Isolate-Search?

In photo 1, the interior of this old wood-frame house sustained extremely heavy fire damage; fireworks had started the fire on the night of July 4. On arrival, Miami-Dade (FL) Fire Rescue (MDFR) companies encountered a large volume of fire; the structure appeared to be fully involved and not survivable. After most of the fire was knocked down with an outside/defensive attack, firefighters found a room that was unscathed, protected by a closed door (photo 2). The lesson learned/reinforced: Don’t give up so quickly on occupants in dwellings that are heavily involved in fire. [See Fire Engineering’s Training Minutes on “Door Control” with Chief (Ret.) Jimm Walsh and Erich Wheaton, https://bit.ly/33ua389.]

(1) Photos courtesy of Miami-Dade (FL) Fire Rescue unless otherwise noted.

(2)

VEIS: Time Is Critical!

In performing vent-enter-isolate-search (VEIS) today, we understand that we must minimize the time between ventilating and isolating. In that interval, the flames, not the firefighters, are in control if the bedroom door is open. The fire will find a flow path into the bedroom and out of the bedroom window; there is nothing stopping it. Firefighters now break out a window and tear out the sash while on the ladder to reduce the time between creating a potential flow path and closing the bedroom door; once that door is closed, conditions will improve.

VEIS vs. Interior Search

VEIS

In a perfect world, you would have sufficient personnel to perform VEIS simultaneously with an interior primary search. But you may not have enough personnel in those first few crucial minutes when a first-arriving company is operating alone. If that company (a ladder or rescue company) does not have water and lacks personnel to perform VEIS and interior search simultaneously, the company officer faces a tough decision: Which will be more productive, VEIS or an interior search? It depends on conditions.

The MDFR staffs medic rescues with an officer and two paramedic firefighters and equips them with self-contained breathing apparatus and ladder company tools. At fires, medic rescues most often perform ladder company duties, such as search and rescue, outside ventilation, utility control, and forcing alternate means of egress for companies operating inside the fire building.

Rescues will also assist engine companies in long, difficult hose stretches and in standpipe operations. Once, a rescue returning from an early morning medical call was dispatched to a house fire in its district, arriving in less than three minutes at a working fire. In a single-family house, a Christmas tree had set the entire front of the house ablaze. Knowing that they would operate alone for a few minutes, the crew went to the rear of the house and performed VEIS of two bedrooms, rescuing an occupant. This was a clear-cut case for VEIS. With no hose or water, the rescue crew could have either waited for an engine company to arrive or taken decisive action; fortunately for the occupant, they chose the latter. VEIS allows firefighters to reach and rescue occupants without getting “nose to nose” with the fire.

Regarding rescuing occupants through bedroom windows, consider the following incidents in which the rescuers were not firefighters. In the first, companies found heavy fire conditions in a single-family dwelling; from the apparatus cab, it appeared the house was fully involved. Police officers arriving before fire units found a window air-conditioner running; pulled it out of the window; stood on it; reached in; and lifted an elderly man out of his bed, which was right below the window (photos 3-4).

(3)

(4)

In the second incident, companies were dispatched to a house fire with a report of children trapped. On arrival, police officers struggled to restrain a hysterical mother attempting to enter the house to save her children, five- and six-year-olds. Suddenly, the children’s father showed up, smashed out a bedroom window with a rake, reached in, and pulled them out. The kids had been left alone while the parents visited a neighborhood bar.

VEIS could be strongly indicated if a family member points out the window of a bedroom where a loved one is sleeping. Neighbors may also provide information, but don’t act on possibly inaccurate information. Ask the neighbor, “How do you know?”

One of the claimed drawbacks of VEIS is that it is too slow because one firefighter can only search one bedroom at a time—he must ladder a bedroom window, enter, perform a search, descend the ladder, and reposition it at another bedroom window. This is not always necessary. If conditions permit, firefighters may, after searching the laddered bedroom, access other bedrooms from the hallway and search them after isolating themselves by closing bedroom doors.

Interior Search

In homes with a conventional floor plan, bedrooms are grouped together toward the rear or to one side of a one-story home and at the top of the stairs in two-story dwellings. But in modern floor plans, the master bedroom is commonly in a different area of the house or on a different floor. Similarly, Cape Cods typically have one bedroom on the first floor, with the rest of the bedrooms on the second floor.

Consider a kitchen fire in a single-family dwelling with a conventional floor plan. In photo 5, the engine company enters the front door and advances a hoseline to the kitchen on the right to control the fire while the ladder company heads to the left to search the bedrooms.

(5) Photo by Eric Goodman.

If a victim is rescued from a bedroom, who gets the credit, the engine or the ladder company? Both. Today’s synthetic petrochemical-based material-fueled fires rapidly intensify and quickly become nonsurvivable for occupants and firefighters. Firefighters who are students of modern fire dynamics know that today’s fires are not going to take a time-out while firefighters perform a search.

Bedrooms located together are conducive for an officer-directed search. The officer, using a thermal imaging camera (TIC), guides a firefighter as he searches. If the search team is an officer and two firefighters, the officer can direct one to the left and another to the right or to different bedrooms. If you are concerned that the crew is not in physical contact, consider these factors: First, if the fire is in an average-size home or apartment, the search team members will remain in voice contact. Second, the firefighters must be experienced and well-trained in firefighting and search techniques. Third, occupants become trapped because in private dwellings, sleeping areas have only one way in and one way out; smoke and fire are blocking that way. Hence, if the firefighters follow the same search pattern, to the left or the right, they will return to their officer. Clearly, this operation is faster than VEIS.

Modern floor plans. VEIS may be unsuccessful or inappropriate if the area or room to search has no door to isolate it from the fire. VEIS will most likely be less effective in searching kitchens, dining rooms, and family rooms because they cannot be isolated. Similarly, “great rooms,” common in the modern home floor plans, are not a good candidate for VEIS. A great room combines the living room, family room, and dining room into one high-ceilinged room that is open to the kitchen.

Firefighters in a South Florida fire department attempted VEIS in what they thought was a second-floor bedroom, unaware that the home had a modern open floor plan. The home had a vaulted ceiling and a loft hallway to the second-floor bedrooms that overlooked the great room. Before the firefighter on the ladder entered through the window, he made a critical error, violating a fundamental rule of VEIS: Always gently probe the floor with a tool to check for a victim immediately below the window and for the presence and integrity of a floor. Miraculously, the firefighter was not seriously injured when he landed on the dining room table on the first floor.

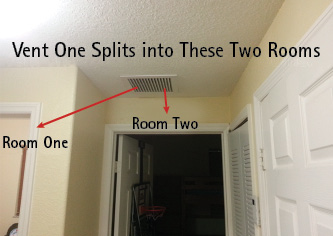

High-efficiency air-conditioning. With conventional systems, air from bedrooms returns to an air handler through the space between the bottom of the bedroom door and the floor. But with high-efficiency systems, the return air ducts in each bedroom typically connect to an air handler in the hallway (photos 6-7). These air returns cannot be closed like air-conditioning supply vents; consequently, a closed door will not totally isolate bedrooms.

(6)

(7)

Isolation. If a closed door can isolate a bedroom during VEIS, it can also improve conditions for the firefighters searching and the victims they seek. When searching a room with a door (e.g., a bedroom), firefighters should close the door behind them to isolate themselves from the fire and the flow path (view video here: https://youtu.be/1QBMahA-1bQ). Additionally, an open bedroom door may hide another door to a closet or a bathroom that must be searched (photos 8-9).

(8)

(9)

Human behavior. Human behavior is critical in search operations. Victims poisoned by toxic smoke and deprived of sufficient oxygen are prone to irrational behavior, such as taking refuge in a shower or closet. Similarly, in a large percentage of fatal fires, victims are impaired by drugs or alcohol. Often, family members are found within an arm’s reach of each other; children will seek their parents, or an older sibling and parents will seek the younger children.

Sheltering in Place

Almost every day, MDFR dispatches the resource equivalent of a structure fire assignment to remove a morbidly obese (bariatric) patient from a bedroom and transport him to the hospital. What if such persons are trapped by fire? What if firefighters locate a victim weighing between 300 and 400 pounds? If the victim is in a bedroom, wouldn’t be better for the victim and the rescuers to close the door, open or break the windows, and stay with the victim until the fire is extinguished and the structure ventilated? Thanks to the isolation the closed bedroom door provides, the smoke will lift, and the bedroom will become increasingly more tenable. Similarly, if a large unconscious victim is located in a hallway, a few feet from a bedroom, it is better for the victim and for the rescuers to pull him into a bedroom and close the door instead of dragging him several feet through heat and smoke to an exterior door. Additionally, consider the risk involved in transferring adult victims of any size to a windowsill and then carrying them down a ladder.

Firefighters conducting a search must ask, Is it in the best interests of occupants to take them from the refuge of a relatively smoke-free bedroom or apartment and drag them down a smoke-filled hallway? In a large city, police told the occupants of an apartment that was clear of smoke, “You have to get out!” The daughter of a 91-year-old bedridden occupant pleaded with the officers to allow her mother and her to remain in their apartment and assured them they would pack wet towels at the bottom of their door. In spite of their pleas, an officer attempted to carry the elderly women out of the apartment and dropped her in the smoke-filled hallway; her body was later found by firefighters.

In photo 10, the fire apartment’s occupant was killed by an intense fire that spread into the public hallway. In photo 11, the soot-covered hallway door of apartment 14N, the unit directly adjacent to the fire apartment, shows signs of exposure to intense heat; the paint is blistered, and peephole is deformed. Photo 12 shows the inside of apartment 14N, its pristine condition a testament to the effectiveness of the shelter-in-place strategy. Clearly, the occupant was safer remaining in her apartment than facing lethal conditions attempting to evacuate by way of the public hallway. Firefighters, whether medically treating a patient or protecting occupants from fire, must remember their guiding principle: “Do no harm.” A protect-in-place strategy is effective in multiple dwellings because, unlike office buildings, residential mid- and high-rises buildings are highly compartmentalized (photo 13).

(10) Photo by Mike Dugan.

(11) Photo by Mike Dugan.

(12) Photo by Mike Dugan.

(13)

Additionally, mechanical codes forbid the air supply to public hallways to intermingle with air in individual residential units. Smoke contamination of residential units is further impeded if units have a fire-rated door assembly leading to the public hallway. A fire-rated door assembly consists of a door, a door frame, hinges, latches, a self-closing mechanism, and gasketing to seal the door from smoke. Gasketing includes a sweep, similar to weather stripping, to seal the space between the threshold and the bottom of a door.

In a post-9/11 world, it is increasingly difficult for firefighters to convince occupants that it is safer to remain in their residential units than to try to evacuate through smoke-filled hallways and stairwells. Without information and direction, building occupants will likely panic, and panic is contagious. Educating occupants that it is better for them to protect/shelter in place begins before an emergency with public education programs.

Although it may be futile, firefighters must make every effort to advise occupants how to protect themselves. Otherwise, firefighters will continue to find deceased occupants in stairwells and elevator lobbies where they succumbed to smoke while they were desperately pushing buttons for an elevator that was never coming for them.

BILL GUSTIN is a 48-year veteran of the fire service and a captain with Miami-Dade (FL) Fire Rescue. He began his fire service career in the Chicago area and is a lead instructor in his department’s Officer Development Program. He teaches tactics and company officer training programs throughout North America. He is an advisory board member of Fire Engineering and FDIC International.