SARA In All Its Simplicity

Features

HAZARDOUS MATERIALS

If you think SARA’s requirements for fire departments are complicated, you’re a victim of the many myths on the subject.

Fire departments are affected by the requirements of SARA— the Superfund Amendments and Reauthorization Act of 1986— because of congressional concern over their members’ safety. If it seems SARA’s greatest protection is that it keeps fire departments from responding to hazardousmaterials incidents by burying them in paperwork, that impression is the result of a number of popular myths about the law.

The requirements are actually quite simple, and they provide information that, with a little crossreferencing, will indeed help firefighters act safely.

Firefighters have traditionally been the emergency responders to haz-mat incidents, but they haven’t always succeeded in learning what haz mats are used in their communities or where they’re stored. Over the years, a wall has arisen between industrialists and local fire departments.

At the same time, there’s been growing and justified concern over the manufacture, transportation, storage, and use of haz mats. People who live near industrial or commercial businesses that make, store, or use haz mats claimed they have a right to know what chemicals are present, what the hazards are, and what to do in an emergency. In March 1985, the Chemical Manufacturers’ Association instituted a program—CAER, or Community Awareness and Emergency Response—to accomplish that. But it was too little and too late to head off congressional action that had been spurred by methyl isocyanate releases in Bhopal, India, and Institute, W.V.

The result was SARA, also known as the Community Rightto-Know Act, of which Title III has the most significance for the fire service.

Title III is about reporting. It lays out at least five different requirements for reporting about hazardous chemicals. In each, the agencies to whom the reports are made are different, and various sections concern different chemicals and threshold reporting quantities. The one similarity is that all the reporting is to be done by “facilities using, making, or storing these hazardous chemicals.” These reporting requirements are precisely prescribed. Thus we come to the first myth about SARA: that local fire departments can dictate how the reporting should be done.

The second myth is that the local emergency planning committee can dictate how the reporting should be done. (The local committee must be established by the state emergency planning commission, which the governor appoints, following SARA’s provisions; it can be the governor or local governmental agencies that appoint the local committee’s members.)

The third myth is that the state emergency planning commission can dictate how reporting should be done.

These first three myths have caused more confusion surrounding SARA than the law itself. Here’s the reporting that the law actually requires:

Section 302, Emergency Planning Notification. This section affected all companies in the Census Bureau’s Standard Industrial Classification Codes 20 to 39, which cover all manufacturers. By May 17 of last year, manufacturers had to file reports if they had on their premises “planning threshold quantities” (defined in SARA) of any of the 406 chemicals the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency has labeled “extremely hazardous.” A list of those chemicals was published in the November 17, 1986, edition of the Federal Register.

The manufacturers’ reports went to the state emergency planning commissions, which had the job of alerting those local emergency planning committees whose districts included a facility covered by SARA.

These reports could be as simple as a letter stating that the facility manufactures, stores, or uses one or more substances on the list. It need not say what the material is, how many materials there are, or how much is present.

Each facility had to name a “facility coordinator” who, working with the local emergency planning committee, would develop an emergency plan covering any accidental release of the extremely hazardous chemical or any other emergency at the facility that might require evacuation of the immediate or downwind areas, or both. The facility coordinator would then meet with the local emergency planning committee and help to incorporate that site’s plan into the community emergency plan that SARA requires local committees to write. The committees must complete these plans, covering every location in their jurisdiction where a toxic release could occur, by October 17 of this year.

This contradicts a fourth myth, that fire departments are responsible for developing evacuation plans in case of a haz-mat release. Fire departments should cooperate in the task, but the job remains with the local committee. In many cases, the plan can be built around one that a local disaster services agency has for evacuation, housing, and feeding of local residents displaced in case of natural disasters such as earthquakes, floods, and other emergencies.

Section 304, Emergency Release Notification. This section concerns releases of any EPA-detined extremely hazardous substance. When a release of a reportable quantity, as defined by SARA, extends beyond the boundary of the facility, a report must be filed with the community’s emergency coordinator (this might be a person selected by the local committee; it’s usually the county disaster services administrator); the state emergency planning commission; and the National Response Center set up by the Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation, and Liability Act of 1980.

Section 311, Material Safety Data Sheet Reports. The most confusing part of the reporting is in this section. By October 17 of last year, all companies in SIC Codes 20 to 39 had to make a one-time-only report to the state and local emergency planning groups and the local fire department if any hazardous chemicals had been present in certain quantities during the past 12 months. The law specifies that companies may fulfill the reporting requirements by providing either lists of the covered chemicals and their hazards, or material safety data sheets.

The MSDSs include synonyms for the substance’s name, and the CAS (Chemical Abstract Service) identification number, hazards of the chemical or mixture, threshold limit value, physical and chemical properties, health effects, reactivity data, fire and explosion data, spill or leak procedures, special protection information, and special precautions. It also states whether the substance is or is suspected of being a carcinogen.

Additional companies have more recently come under Section 311’s provisions, so that now SARA covers all businesses that have on their premises a reportable threshold quantity of any covered chemical. The additional companies have until May 23 of this year to be in compliance.

The threshold amount that must be reported is 10,000 pounds for hazardous chemicals, defined in this section as any chemical compound or mixture for which the U.S. Occupational Safety and Health Administration’s Hazard Communication Standard requires the chemical manufacturer to send the user or storer an MSDS.

(At the time of the manufacturers’ reporting, the Hazard Communication Standard listed 23 hazards; a chemical that presented any one of these threats was listed as a hazardous chemical. Since then, the EPA has consolidated the list into just five items: acute health hazard, chronic health hazard, fire hazard, reactive hazard, and sudden-release-of-pressure hazard.)

The threshold quantity is just 500 pounds for extremely hazardous chemicals.

Despite the complexity of what companies, chemicals, and quantities are covered, for individual businesses the decision on what to report is simple. They check all the chemicals for which MSDSs have been provided, check which of these were present in the threshold quantities in the last 12 months, and report them to the appropriate authorities.

Here’s where those first three myths popped up.

Some fire departments feared they’d be buried by MSDSs, so they instructed companies in their district to report by providing the list. Other fire departments insisted they needed MSDSs and refused to accept lists. At the same time, many of the local and state emergency planning panels decided they could set up their own reporting rules.

The truth of the matter is that neither fire departments nor the local or state planning groups can insist on either form of reporting. The decision is up to the reporting company. Certainly, the spirit of cooperation between fire departments and industry can be furthered if the fire departments make a polite request for the type of reporting they would prefer and if companies do everything they can to honor the request.

That spirit can quickly dissipate if fire departments persist in believing Myth No. 5—that they must keep files of MSDSs to be given to anyone who requests them. In reality, it’s the local committee (and perhaps the state commission) that must provide the information. There’s nothing in the law that even remotely suggests that the local fire department must provide any information to anyone. Indeed, fire departments might even be liable for damages if they disseminate any information concerning chemicals present at any place of business.

Section 312, Inventory Forms. Reports in a different form are due to fire departments, local emergency planning committees, and state emergency planning commissions each year on March 1. All facilities having hazardous chemicals present must report the aggregate amounts by each of the five hazard classes the EPA has defined and the general location of the chemicals in the facilities. This is socalled Tier I reporting.

For any particular chemical, any of the agencies to which the report is sent may request Tier 11 information—the name of the chemical, its CAS number, the amount present, the type of containers, and the specific location.

The Section 312 annual reports begin this year for facilities in SIC Codes 20 through 39 and next year for all other facilities.

Section 313, Toxic Release Reporting. Effective July 1 of this year, accidental releases of reportable quantities that spread beyond the bounds of the facility will have to be reported to the EPA and a state official designated by the governor. This section applies only to facilities in SIC Codes 20 through 39 that have 10 or more full-time employees and manufacturered, processed, or otherwise used a toxic chemical in excess of its planning threshold quantity in the year preceding the release.

Congress created these reporting requirements in SARA partly to make the fire service a repository for information on hazardous chemicals. The reason was to give fire departments an opportunity to learn what haz mats are present in their jurisdiction, in what quantities, and with what hazards associated. Congress assumed that if a fire department has this information, it will use it to educate, train, and equip its first responders to handle almost any chemical emergency.

The problem is how to assimilate all the data. Each fire department must face the problem in its own way, and many will find their own solutions. But for those that lack the resources to handle the influx of information, I offer the following system as a solution. It should work for the largest of career departments and the smallest of volunteer departments, and all others in between.

It involves adding two files to your existing preincident plan for manufacturers and warehouses in your protection district. Even if you don’t have such a plan, you should compile and cross-reference the SARA information.

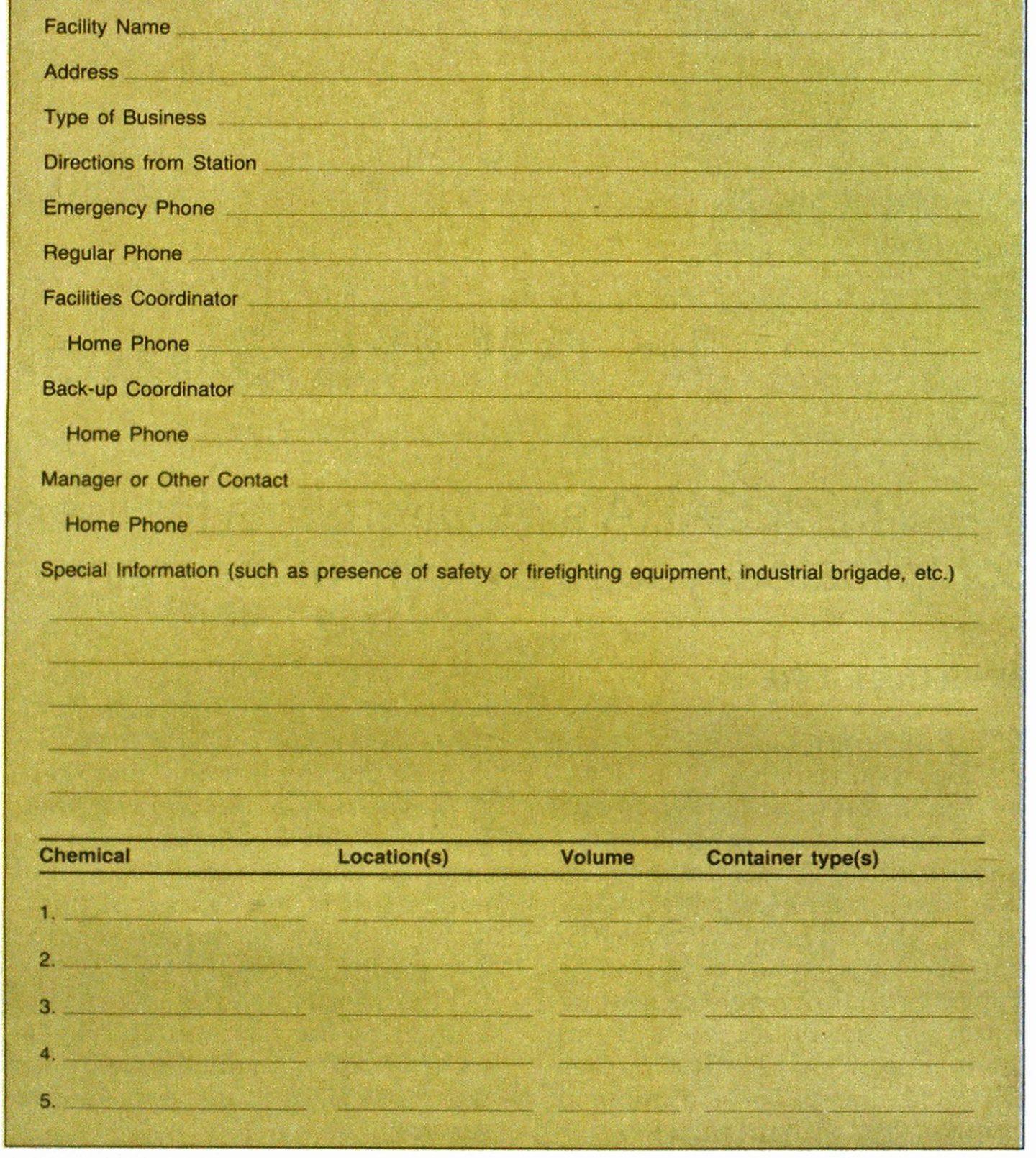

The first file contains information about the facility and the people in charge. (See Figure 1 on page 44.) The top of the form is probably identical to your prefire plan. In this case, though, the main contact will be the facilities coordinator named in the Title III reporting. This might be the plant manager; there should always be at least one back-up. The plant manager or owner might ask to be notified (in addition to the facilities coordinator) in case of an emergency.

The second file consists of information about the individual chemicals. (See Figure 2 on page 45). You may already have some of the information available from MSDSs or the data sheets you may have been compiling from the Chemical Data Notebook Series in Fire Engineering. [See page 65 of the September 1987 issue.]

The chemical file should list the most common synonyms for the chemical name, as well as a variety of identification numbers and ratings. The latter include the CAS number, the four-digit UN/NA (United Nations/North America) number used by the U.S. Department of Transportation, and the seven-digit STCC (Standard Transportation Commodity Code) number, which always starts with the two digits 49. Others to list are the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health’s RTECS (Registry of Toxic Effects of Chemical Substances) number; the U.S. Coast Guard’s CHRIS (Chemical Hazard Response Information System) number; and the IMO (International Maritime Organization) number.

The DOT hazard class is the one that federal agency assigns for the material’s greatest hazard in transportation. The National Fire Protection Association 704 Hazard Rating appears in a diamondshaped design divided into four quadrants. The left quadrant (colored blue) represents the health hazard, the top quadrant (red) represents the flammability hazard, and the right quadrant (yellow) represents the reactivity hazard. The bottom quadrant (white) indicates if the substance is an oxidizer or is water-reactive or radioactive.

“Delivery by” means the method (truck, rail, pipeline). There’s no requirement in SARA about getting delivery information, but you should ask the facilities involved for it and incorporate it into the overall community emergency plan so the routes used by the deliverers can be identified.

The average volume on the premises comes from the information provided by the facility.

It’s clear from looking at these forms that SARA isn’t complicated. It’s the actions of each of the agencies involved that have produced the complications, misinformation, and myths surrounding the law.

The fire service’s job under SARA is simple: Request this information from the covered facilities in your district, politely specifying whether you prefer MSDSs or lists of chemicals. When the time comes for Tier I reporting, go over the material carefully to decide for which chemicals you’ll want Tier II information—those about which you have little information and those which are particularly hazardous. Make the Tier II request politely, also.

Once you have the information, begin to organize it in the two files I’ve suggested or in whatever other system you have appropriate to the task. As you coordinate the information in the two files with your master preincident planning file, a pattern should develop that will enable you to make meaningful input into the SARA-required community emergency evacuation plan.

And a more important pattern will become apparent: a pattern of the need for education, training, and equipment. Through MSDSs and other reference materials, you’ll have all you need to know to prepare your department to respond to and mitigate a haz-mat incident safely.

Through the pattern of delivery methods, volumes, and frequency of shipments for each chemical, you can prepare your department to handle transportation incidents safely. The totals on each chemical can tell you what chemicals are coming into, being stored and used, or being manufactured in the greatest volumes. From that you can rank the chemicals by importance to your district.

Don’t feel that the burden of planning for all chemical emergencies rests on your fire department. That job clearly falls to the local emergency planning committee. Take an active role in the implementation of SARA, but don’t assume the work is all yours. Do what’s important to the fire department: Prepare to handle the information coming in, then use it for your safety and the safety of your community.