By Scott Finazzo

Overland Park, Kansas, is a sprawling suburban community, perpetually evolving and teeming with growth. In various areas around its vast 75 square miles, new construction can be seen breathing new life into an already progressive city. Housing subdivisions, apartment complexes, office buildings, and several mixed-use properties are rising in the shadow of nearby Kansas City.

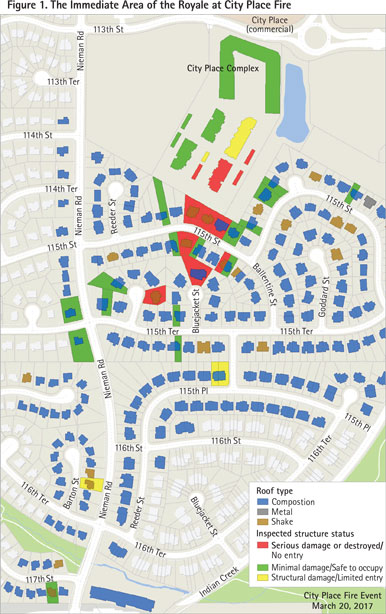

One such construction project is the Royale at City Place (City Place) “luxury apartments.” Royale sits conveniently near the bullseye center of Overland Park. On March 20, 2017, the five buildings within the complex were in varying phases of construction. One building was complete and occupied, some appeared to be nearing completion, and others were still in the framing process. The project appeared, all in all, to be no different from any other apartment complex being built anywhere else in the country.

|

| Buildings, single-family homes, and duplexes burned simultaneously as crews battled to get the fire under control. |

That would all soon change. Because of what investigators later determined to be the result of sparks from a welder, a conflagration unlike any ever seen in the Kansas City area occurred. A fire in an unprotected building under construction, fueled by spring winds, resulted in an eight-alarm fire of epic proportions. Over the course of about 12 hours, six structures in an apartment complex and 32 nearby homes within an area that covered more than a mile received some type of fire damage.

The Fire

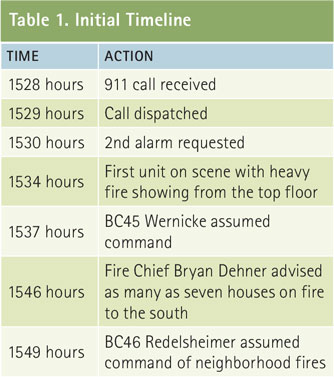

It was a sunny Monday afternoon. The temperatures hovered near 80 degrees, and winds were out of the north at about 10 miles per hour. At 3:28 p.m., a building fire was reported at the construction site where City Place apartments were being built. Five units were dispatched and responded. Overland Park Fire Department (OPFD) operates within a countywide system that has long-standing automatic-aid agreements in place. The initial alarm included three fire apparatus from OPFD and two from Lenexa (its neighbor to the west), plus an OPFD battalion chief (BC) and ambulance. First-due fire units reported heavy smoke showing from several miles away. BC Grant Wernicke (BC45), who was the initial responding BC, noted the massive column of smoke while en route as Engine 44 Captain Pat DuPont ordered a second alarm three minutes prior to anyone’s arrival.

Wernicke was familiar with the area and knew that there were several multistory buildings under construction. The layout of the complex made it difficult to pinpoint the structure that was on fire because it was obscured by the other buildings. While en route, the first on-scene apparatus reported heavy fire from the top floor. Wernicke arrived on scene and assumed command.

Initial Actions on Scene BC Wernicke

Since the scene was an active construction site, accountability was a concern and a significant challenge, but there were no initial reports of anyone inside, so Wernicke was comfortable initiating a defensive attack with a focus on exposure protection. Workers were scrambling to move their vehicles and equipment out of the way of the incoming fire units. One alert worker relocated a diesel fuel tank that had been placed next to the building that was now on fire. This building did not yet have gypsum board or windows installed. It was basically four stories of lightweight wood truss construction. Knowing that this would be a big water event, Wernicke requested all incoming aerial apparatus come to a forward position and engines to locate a hydrant and ensure adequate water supply to the aerials. Fortunately, hydrants were already in place and functioning within the construction site. The sprinkler system was in place, appropriate for the time schedule of construction, but was not complete or in service.

![(1) Within minutes, a spark from a welder ravaged the apartment building under construction.<i> [Photos 1-2 by Jason Rhodes, Overland Park (KS) Fire Department.]</i>](https://emberly.fireengineering.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/1710FE_Finazzo-Photo_1.jpg) |

| (1) Within minutes, a spark from a welder ravaged the apartment building under construction. [Photos 1-2 by Jason Rhodes, Overland Park (KS) Fire Department.] |

The first-alarm aerials lined the Alpha side of the building on an unpaved road. A parking garage between them and the fire building was already steaming and ready to light off at any moment from the radiant heat from the fire building. Everyone on scene immediately noted the firestorm building in front of them. The radiant heat was fierce and was already melting the Tyvek® wrap on the Alpha exposure, which was on the other side of the units setting up to fight the blaze. Crews knew they had a small window of time to put lines in place to keep the Alpha exposure from lighting off, which would mean they would be right in the middle of two building fires.

BC Redelsheimer

BC Brian Redelsheimer (BC46) heard the initial radio traffic of incoming units and began to head toward the fire. While en route, he was assigned to the second alarm. On his arrival, he drove to the Charlie side, the direction in which the wind was blowing large amounts of smoke and debris.

“As I arrived on scene, I had three thoughts,” recounts Redelsheimer: “This is an exceptionally hot fire. I couldn’t get around to the Charlie side because the scene was a construction site. Behind the Charlie side, there is a field, and across that field were two houses on fire.”

Before Redelsheimer could notify command that the incident was growing, dispatch alerted that it was receiving calls from the adjoining neighborhood reporting multiple houses on fire. Wernicke assigned BC46 to command the neighborhood while he remained in place to command the building fire.

Near the Royale building sat a large vacant field that separated the budding apartments and a subdivision of single-family and duplex homes. The radiant heat was so great that the wood shake shingle roofs of the homes caught fire, as did the surrounding wooden privacy fence. Redelsheimer’s initial action plan was to knock down the fires involving the two houses, initiate exposure protection, and address the reports of other house fires in the neighborhood.

|

| (2) The City Place fire created a thermal column that erupted burning debris that rained down on nearby neighborhoods, creating fires that it would take more than eight alarms to contain. |

At this point, the thermal column from the Royale building fire had grown so strong that it began to emit burning debris that cascaded down on the neighborhood to the south. Redelsheimer likened it to a biblical event: “It was like something out of the Old Testament.” Dinner plate-sized burning debris rained down. It was landing on the homes, in the street, in bushes, and even on the firefighters trying to get a handle on the rapidly growing event.

As the first apparatus was setting up to control the house fires, burning brands landed on its supply line and caused it to burst, hindering the initial attack. During the firefight, several other attack lines were destroyed as burning fragments of construction debris rained down on them. At one point, a burning piece of plywood landed on the command vehicle; the operator of a nearby quint, who was repositioning the elevated master stream, swept across the hood of BC46 and extinguished the fire.

Second-alarm units were arriving and approaching the scene primarily from the south and west. As they arrived, Redelsheimer immediately put them to work in defensive operations and exposure protection of the multiple houses that were now burning. The only problem was that Wernicke, who was expecting a second alarm to his building fire, was not immediately aware that his second-alarm units had gone to work in the neighborhood. Once he determined what had occurred, he ordered a third alarm to report to the Royale building.

From his position near the two burning houses, Redelsheimer noticed a preconnected 1¾-inch hoseline being advanced to the house where he was parked. That house was now on fire. As he repositioned the command vehicle, reports of house fire after house fire in the neighborhood were coming in. Redelsheimer knew this incident was growing and that it was time to set up a formal command structure. BC Jeff Doherty, from the nearby city of Olathe, arrived and was assigned “West Division,” which included everything west of the BC46 vehicle.

|

| (3) Apparatus were positioned in place to protect exposure buildings in various stages of construction. (Photo by Addie Chapin.) |

Units initially struggled to get a handle on the incident because burning debris was bursting lines, landing on the hosebeds of fire trucks, and creating small spot fires all around them. The homes with wood shingle roofs seemed to be the most vulnerable to fire. As each house fire was reported, the emergency communications center (ECC) dispatched a separate alarm for each house, quickly depleting OPFD resources and drawing in units from nearly every nearby city.

The thermal column of the Royale fire continued to erupt burning debris and rain it down on the nearby neighborhood as Wernicke was setting up a large-scale defensive operation of the buildings amidst the fallout. On the arrival of the third-alarm companies (the second alarm sent to him), he began to set up divisions around the building. The immediate next building to the north (exposure B) was now on fire as well; the top floor was approximately 25 percent involved. The fire advancement in the exposure building was slowed, in part because the wind was blowing from the unburned toward the burned.

As the scope of the incident was becoming apparent, so was the acknowledgment that exposure protection, already a priority, was critical. The fallout from the fire building (and now part of a second building) was wreaking havoc on the neighborhood to the south. The sphere of the incident had expanded from one building fire to two buildings and a growing number of nearby houses. The OPFD senior staff began to converge and set up a centralized and formalized command.

Crews reverted to experience and training and coordinated with other crews when they could, but they often operated independently, noted Redelsheimer. Many times, they were faced with the decision of whether to go in homes to extinguish manageable fires before they became large fires or to remain outside in a purely defensive posture. Ambulances set up makeshift rehab areas, which was a challenge because of the transient nature of the crews going from fire to fire. Companies battled house fire after house fire well into the small hours of the morning.

Operations

Chief Bryan Dehner took over as incident commander and requested assistance from nearby Kansas City, Kansas; Kansas City, Missouri; and Lawrence, Kansas; the ECC modified their radios so that they could use the same tactical channels. He assigned Deputy Chief (DC) Mike Casey to Operations. Three branches were established: City Place Branch (directed by BC Wernicke), 115th Street Branch (directed by BC Redelsheimer), and 117th Street Branch (directed by Lenexa BC Randy Maines), which was responsible for all incidents occurring south of 117th Street.

Casey immediately began to determine what resources were on hand and where they were located. Because units in the neighborhood were going house to house putting out fires, it was difficult to determine what resources were on scene and where they were. Casey worked with other assisting chiefs and ECC representatives in the command vehicle using a mobile data terminal (MDT) to locate apparatus and begin to organize, as the incident had expanded to eight alarms that were spread out throughout a growing geographical area.

The initial action plan of Operations was to use natural city breaks to prevent the conflagration from growing beyond specific boundaries. Hard lines were drawn at major streets and would shrink as the incident came under control. Crews battled tirelessly going from house to house doing everything they could to keep the flames in check. There were many reports of police officers with portable fire extinguishers and citizens with garden hoses putting out spot fires in yards, wooden decks, and shrubbery.

|

| (4) Fire raged on both sides of the street as master streams and hoselines were moved from house to house. (Photo by Spencer Carey, The Campus Ledger, Johnson County Community College.) |

“We’ll never know the impact of the individual efforts made by crews and residents. Every small fire put out with a garden hose or stomped out with a shoe could have been another house on fire,” noted Casey.

As the number of house fires reported had swelled into the teens, the initial building collapsed. This catastrophic event proved to be pivotal to the incident.

“Everything got better when the building collapsed. The erupting volcano slowly collapsed on itself and became a large pile of wood,” explains Wernicke. The collapse altered the thermal column enough to halt the airborne burning debris. From the initial setup, crews remained outside of the collapse zone and operated at a safe distance, which meant the building collapse was a blessing.”

Wernicke’s BC vehicle was parked to avoid obstructing access to or egress from fire trucks; consequently, he had no line of sight on the fire building. Therefore, early in the incident, he set up a makeshift post composed of a 55-gallon drum with a pallet on top to direct his branch. Off-duty personnel had shown up and were used in “aide” roles. Wernicke credits preexisting relationships and ingrained trust with helping him to manage the City Place building fires. There were times when chiefs on varying sides of the building would take a few pictures on a cellphone and send a runner to offer Wernicke a visual of areas of the building he could not see to help him make tactical decisions.

![(5) Wood-shingled roofs burned throughout the neighborhood. <i>[Photo by Jason Rhodes, Overland Park (KS) Fire Department.]</i>](https://emberly.fireengineering.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/1710FE_Finazzo-Photo_1.jpg) |

| (5) Wood-shingled roofs burned throughout the neighborhood. [Photo by Jason Rhodes, Overland Park (KS) Fire Department.] |

With the initial building fire now on the ground, Wernicke maintained steady master streams on it, but he focused his resources on exposure B. This exposure was being kept in check, but the top several floors were still burning.

IC Dehner had established a unified command center in the mobile communications unit. It was primarily fire, police, and medical, although through the city’s emergency operations center (EOC) at a remote location, every city department was being used in one form or another. Prevention Chief Mark Sweany had a bird’s eye view from a local news helicopter and reported updates to command from the air. The formal command structure had taken shape.

Redelsheimer had divided the 115th Street branch into three geographical divisions. As you can imagine, the tactical channel assigned to the 115th Street Branch was chaotic at times. As with the City Place Branch, chief officers were acting as runners and bringing back status reports of unit locations and incident updates. The torrent of raining fire debris had ceased, and Redelsheimer saw this as a time to get a stronghold on his side of the incident.

Because of the sudden rise in the number of house fires in the neighborhood, accountability was handled at the company level. Unit officers were trusted to be disciplined and maintain a defensive posture and focus on exposure protection. A police department captain sat in the BC vehicle with Redelsheimer and assisted in strategizing and fielding requests for evacuation assistance. They would look up the address on the MDT and determine if an immediate evacuation was necessary. As mutual-aid BCs reported, Redelsheimer assigned them to supervise streets or cul-de-sacs, not houses, within a division.

The police department had obtained permission to use a nearby church as the gathering place for neighborhood residents to convene and receive status updates and assistance. Residents were directed there as an outpouring of community support began to flood the area. Grocery stores, restaurants, generous citizens, and a variety of others brought food, water, and supplies for responders and displaced families.

|

| (6) Crews continued to flow water well into the next day to ensure that the fires had been fully extinguished. (Photo by Addie Chapin.) |

Meanwhile, at the Royale building, apparatus were running low on fuel and diesel exhaust fluid (DEF). The EOC coordinated with public works to have a diesel fuel tank and several cases of DEF delivered. This proved to be yet another obstacle. Once they were delivered, there was no way to get supplies to the apparatus that needed them. Fire apparatus and charged hoselines obstructed every access option in an already precarious construction site. Public works employees commandeered as many fuel cans as they could and, with the help of a smattering of unassigned firefighters, hand carried cans of fuel from the tanker to the units. It was an “all hands” event, and all hands were doing whatever it took to bring the incident under control.

Hours later, as the incident was in decline, the initial fire building lay in a pile of burning debris surrounded by flowing master streams, and the fire in the top two floors of the exposure B building had been brought under control. Two parking garages were destroyed; several other buildings were scarred with drooping Tyvek® wrap and various other signs of melting and charring.

In the subdivision, when the fires were extinguished and the crews were finally able to take a moment to absorb what had happened, Redelsheimer was still hard at work ensuring all three divisions in his branch had accountability and began to formulate a demobilization plan. “Everyone relied on their training. They did things fundamentally safe. That was the basis for operations. Very little command directive. Tactics and strategies were as basic as they could be: defensive operations, exposures, and don’t get hurt. And that’s what people did – more than 50 fire trucks worth of people,” he says retrospectively. “What a testament to the individual skills of the fire companies and the benefits of good working relationships within the department and neighboring departments.”

Throughout the night, crews cycled in and out. The last fire trucks cleared the scene nearly 24 hours after the fire was reported. When it was all over, there was more than $23 million worth of damage. The water department reported the use of approximately three million gallons of water from nine hydrants. Six structures in the City Place complex and 32 homes sustained some type of fire damage. Nine more were uninhabitable, and the remaining 24 had fire damage varying from slight to heavy. Damaged homes were reported as far as nine blocks away. Eight alarms comprised of representation from 11 fire and EMS organizations worked tirelessly to stop this catastrophe in its tracks. Zero civilian injuries were reported; there were three minor firefighter injuries.

Lessons Learned

Even though the mitigation of the incident was considered a success, there were some lessons learned. If one were to sit down at a table and draw up the City Place fire scenario, resources would be placed in optimal tactical locations in a timely manner. The reality is that the incident advanced more quickly than resources could arrive. Crews were behind before they were on the scene.

The OPFD has identified the following areas for improvement should an incident of this magnitude occur again.

- Establish a formal staging area. The pace of the growth at the City Place fires did not allow for a formal staging area. If the situation permits, establish a formal staging area early.

- Make sure separate house fires are treated and dispatched as exposures rather than as individual incidents. The ECC designated each house fire as a separate incident, which complicated accountability.

- Have a physical separation, such as separate command vehicles, between Operations and Unified Command. As chief officers arrived, the command vehicle became overcrowded. Keeping a separation between the two would help alleviate pressure created by sheer numbers.

- Request early chief officers for forward supervisory positions. The scope of this fire was quickly acknowledged, but the formalized command structure could have been established earlier if the chief officers had been assigned earlier instead of when they arrived with their respective alarms.

- Have callback and crew rotation procedures in place. Bringing in off-duty personnel and cycling them into the scene was cumbersome. Having a plan in place would streamline the process.

- The construction crew had a “hot work permit,” which required them to have safety measures in place including someone to monitor the work being done during the “hot work” with safety equipment. This reinforces the importance and skills required to be that person.

- Radio bandwidth became an issue. It was maxed with more than 5,000 radios listening in (on site portables, truck mobiles, other stations, chief officers, etc.). Delegate other channels for use during an incident of such magnitude.

In the hours that the City Place buildings and the surrounding subdivision were burning, more than 100 firefighters were tapping into their personal reserves to stop the assault. Mutual-aid companies worked independently and together in ways they had never been tasked before. Every citizen, firefighter, paramedic, and police officer who participated has their own story to tell of the City Place fire. There are multiple examples of individual deeds that, when combined, produced the best possible outcome with no loss of life. BC Redelsheimer summarizes, “Fundamental strategies and tactics saved the day. The relationships established ahead of time paid dividends when we needed them most.”

SCOTT FINAZZO is an 18-year veteran of and a lieutenant/EMT with the Overland Park (KS) Fire Department. He has an associate degree in fire service administration and a bachelor’s degree in management and human relations. He is an instructor and has authored five books, including The Neighborhood Emergency Response Handbook and The Prepper’s Workbook.

Toothpick Construction: Enough Is Enough

Toothpick Construction: Enough is Enough, Part 2

Picking Apart Toothpick Towers

Fire Engineering Archives