After starting Project Mayday in 2015, we are now finishing our fifth year of learning about Maydays, firefighters, company officers, and incident commanders (ICs), especially with regard to their responses, actions, errors, and decision making. We have also learned the who, what, where, when, and how of the more than 6,438 Maydays that have occurred. They are reported to us by fire departments and victims by phone, e-mail, and text; some state fire marshals forward us their reports. We then send out a three-part survey and do a follow-up phone call with a victim, IC, or safety or training officer. Over the years, we see trends and patterns develop that give us the information we need to prevent many Maydays. This article reviews some of this information as well as some of our recommendations in preventing Maydays.

RELATED FIREFIGHTER TRAINING

Every Second Matters in a Flashover

Fireground Communications: From Size-Up to Mayday

Walton: Mayday, Mayday, Mayday…

Handling the Mayday: The Fire Dispatcher’s Crucial Role

Standard Operating Procedures

When it comes to calling a Mayday, rapid intervention teams (RITs), communications, and incident command, everything starts with standard operating procedures (SOPs). These SOPs are written using National Fire Protection Association (NFPA) standards as guidelines. They are written with good intent, but they should be tested before implementation and, if need be, revised. Once they are implemented, train on them to meet and match their criteria. Make sure you define procedural actions, when to establish the RIT, and the functions of the RIT group supervisor. Units assigned as the RIT should maintain their normal identifiers. If you use crews in close proximity to the Mayday, they must provide their supervisor with actions to consider or take as well as a Conditions, Actions, and Needs (CAN) report.

In addition, define the difference between “rapid extrication” and “extended operations.” Tell the Mayday victim what you want him to DO and what he should expect when the Mayday is confirmed. If there are any flaws or problems, fix them right away. The most important aspect of SOPs is that they must be enforced. All too often, we ignore issues or let them slide, thinking they will go away or fix themselves; this is usually not the case. Company officers are usually the first to see these violations and should correct them.

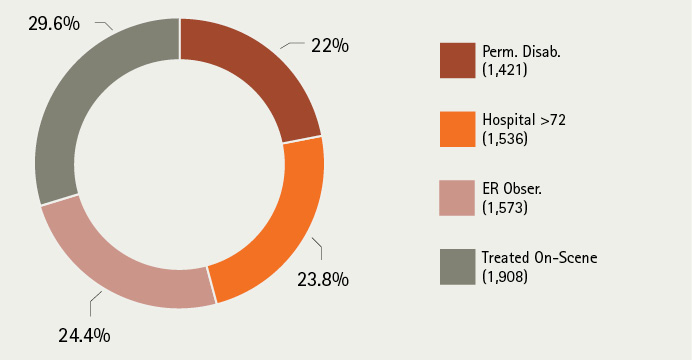

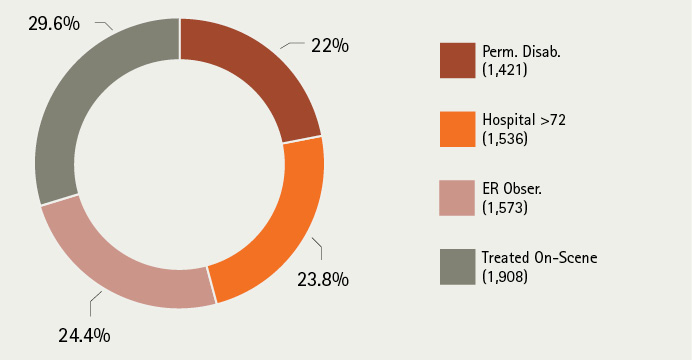

Figure 1. Injuries from Maydays (Career)

Also, make sure a fire department representative is assigned to each transported member as a liaison to the family and an advocate for appropriate care. Provide relief for members directly affected. What information do you want the Mayday victim to pass on to the IC? At the very least, this should include his unit, rank, and name; a description of the situation; his location; and how much air he has left.

Consistently practice, enforce, and reinforce with your members your most important SOPs and explain why the SOPs should be done right the first time; your fellow firefighters are depending on it. Consistent practice of these SOPs is important because you want the same results each time you need them. One missed step could mean the difference between rescue and recovery. Review SOPs at least every three years, making sure to use the most recent NFPA standards as guidelines, along with new training and techniques.

Training

Base your training on your SOPs and have it cover self-rescue and RIT operations. Your first step is to develop a training plan by involving initial and refresher training, using the same instructors to write and deliver the program. It’s important to have consistency in your message. Even more important is the consistency in the answers given to the members’ questions so they understand your message.

Next, initial training that strictly follows your SOPs should occur in the classroom and on the training ground. Everyone, including battalion chiefs, must take part so they have a complete understanding of what a Mayday victim experiences and the difficulty of self-rescue, how important their crew and other interior crews are to the rescue, and what issues the RIT may face. You also need to develop, build, or borrow props from other departments.

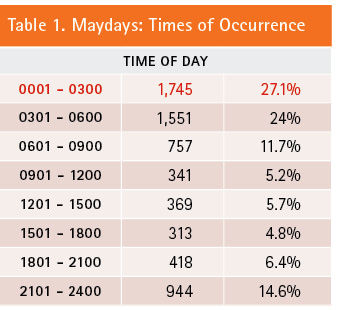

Other important aspects in your training should involve using sound effects such as smoke alarms, low-air alarms, and personal alert safety system (PASS) units. Conduct your training in smoky, zero-voltage, and zero-visibility conditions (71 percent of Maydays occur at nighttime). Also, train on separating a down firefighter from his self-contained breathing apparatus (SCBA)/PASS unit, and practice removal techniques using various pieces of equipment such as the face piece, regulator, and harness.

Every Monday, Project Mayday supports Mayday station training, discussions among firefighters, walk-throughs, and practical exercises that include a more intense self-rescue and RIT training regimen each May. Also, review Maydays in your department, area, region, or state, and then replicate these Maydays and the challenges they present.

One of our most important areas of training involves training company officers in commanding a Mayday. Thirty-four percent of Maydays occur prior to the battalion chief’s arrival. Like it or not, company officers are in the “hot seat,” so make sure they are trained to perform and do it right. In our interviews with many company officers, they felt they were not prepared to deal with a Mayday that has limited resources.

Communications

Let’s start with response. During your training, play some of your good and bad radio reports and have students tell you what was missing or wrong in the call. Practice size-up procedures and 360° walk-arounds with students and then ask them if anything during the tactic was missing or forgotten from their initial report.

One of the things we hear about when discussing initial radio reports is the use of verbiage that doesn’t inform command or anyone else on the fireground. If we say, “E6 to command, we have heavy smoke, moderate heat conditions,” or “E10 to command, we have moderate smoke and light heat conditions,” then we need to be more exact with our interior radio reports. Often, what we hear is, “We have heavy smoke and moderate heat.” What do those definitions look like?

Another example would be, “E6 to command, we have thick black smoke under pressure at our waist, shot the thermal imaging camera (TIC) at the ceiling, and have 500°F+,” or “E10 to command, we have brown smoke to the floor, shot a TIC to the ceiling, and have 350+F°.” This tells more to command than any other descriptions, especially since they can’t see what’s going on inside. So, make sure to confirm all of your communications; it’s the only way to know that all are on the same page. This holds true for Maydays, 35.6 percent of which are missed on their first call.

Finally, consider a better enunciation of key phrases such as “E-1-6,” not “E16”; “L-4-3,” not “L43”; and “Delta side,” not “D side.” The Federal Aviation Administration and the U.S. Air Force have used these for years (i.e., “Runway 2-4,” not “24”) to avoid any misunderstandings.

Types of Maydays

As of the end of 2019, the types of Maydays and their level of occurrence are as follows:

- Lost/Separated from hoseline: 21.6 percent (1,391).

- Falls into basements: 19.6 percent (1,262).

- Air problems: 19.3 percent (1,242).

- Falls though roofs: 15.3 percent (985).

- Explosion/Collapse, Medical, Other, No Communication: 14.6 percent (940).

- Entanglement: 9.6 percent (618).

These Maydays took place in the following occupancies:

- Residential: 43.5 percent.

- Commercial: 41.7.

- Multioccupancy: 14.8 percent.

Lost, no hoseline on entry. These Maydays occur when crews enter the structure without hose. There are many reasons to conduct this task such as faster crew deployment, easier search operations, and the ability to multitask. I’m not a fan of entering burning structures without a hoseline, which is to say that one will be brought in. If this task is a training practice or routine, crews should be comfortable with this operation. However, if it is not part of the everyday routine, do not practice it.

Separated from hoseline. My department’s Mayday victims have said that the reason they got off the line was to search a larger area more quickly or to split the crew into smaller numbers to conduct faster, more thorough searches. We need to rethink our tactics as they relate to large homes (5,600 square feet or larger) and commercial structures. Sometimes, we use a residential mentality in fighting commercial structure fires, which usually gets us in trouble.

Many of our Mayday firefighters also told us that they often came up short of hose, requiring the line to be extended—NOT a good idea since it means you will be in a structure on fire with NO water. Always size up the structure’s size and then ask yourself how much hose will be left outside (between the engine and the entrance), then ask how much you have to conduct your search. Remember, if something goes wrong, the hoseline serves as your egress marker for escape.

Falls into the basement/trapped. The occurrence percentages for these calls are as follows:

- Floor above basement (collapsed): 43.2 percent.

- Floor above basement (hole): 32.9 percent.

- Basement/Stairway collapse: 14.1 percent.

- Under flooring/ceiling collapse: 7.8 percent.

Basement visible during 360° size-up. Many things work against us during structure fires; it’s the unknown that often gets us into trouble. For instance, delayed discovery + delayed notification = sometimes delayed response. If you conduct a 360° size-up, can you see basement windows and, if so, are they heat-stained, cracking, or discolored? Using a TIC wouldn’t help much in identifying a fire or its size.

Also, we often enter these structures standing up, especially when there is smoke to the floor, which is when we should be crawling. When we crawl, we see or feel things such as floor discoloration, ash-hardened rug fibers, and smoke coming off the rug that indicate a fire is below us. Wood and tile floors give off indicators as well, so probe the floor ahead of you.

Again, we don’t often have enough hose to cover the entire basement or any protection line at the top of the stairs leading to the basement. Ensure the area of attack has enough hose at the top to make a difference. Often, opening the door at the basement entrance will change the flow path.

Another problem is that many basements have multicompartments. In our surveys, we found that 40 percent of our Mayday victims fell in a basement and landed on their backs and, thus, their SCBA cylinders, causing back injuries. We also found that 89 percent of these Mayday victims had also lost the seal on their face piece. Some struggled to get a reseal, especially those involved in flame impingement. Make sure to identify fire conditions at the bottom of the stairs. The one training we don’t do enough of is basement Mayday victim removals.

Falls through or off roofs. The occurrence percentages for these calls are as follows:

- Roof travel: 57.6 percent.

- Ventilation point: 25.9 percent.

- Fell on roof or ladder: 16.4 percent.

Roof travel is dangerous when you don’t probe the roof or look for signs of fire in the attic. Also, 88 percent of roof operations occur at night, making an already dangerous operation even more so. In addition, 70 percent of Mayday victims fall through to the rafters. Only 17 percent can self-rescue out of the hole. And, 27 percent were injured, primarily from burns sustained on the lower legs. In addition, 77 percent of Mayday victims have their face pieces dislodged and must reseal; more than 56 percent of these Maydays occurred over garages and porches. These areas are not as well-designed or insulated. As a result, most victims have trouble getting to their radio. It is best practice to punch or kick through the ceiling to alert crews below of your position.

One of the most difficult rescues is an unconscious firefighter or one with serious injuries stuck in the rafters. It will take a four-, six-, or eight-person RIT with ladders, hooks, and chain saws to aid in the rescue. However, our biggest problem is putting too many people on the roof; there can be no spectators as members cut the hole and move to get off the roof!

Air issues. The occurrence percentages for these calls are as follows:

- Low on air (< 500 psi): 48.8 percent.

- Out of air (0 psi): 40.4 percent.

- Other: 10.8 percent.

Several things affect our use of air including age, weight, general health, size, fitness and stress levels, and work intensity. It’s important to teach firefighters different breathing techniques such as box breathing, straw breathing, skip breathing, and so on to conserve air. Remember, every time we break our face piece seal, we will inhale gases and smoke, which will create our greatest health concerns. If you have the new NFPA standard version for SCBAs, understand “the one-third rule,” data logging, and PASS unit operations (sound/alert).

Hoarder structures were involved in 781 of our Maydays, creating a variety of issues. Remember, all departments should have an SOP for these structures, so slow down, make sure you have a real second means of egress, and don’t overload the floor with people and water. One out of nine RIT operations will have a Mayday call, and it will usually be the worst incident to which they responded. Make sure you have a RIT for the RIT. Make sure the RIT is prepared with the right equipment for the Mayday response and mentally ready to perform.

When it’s your time to call a Mayday, ask yourself: How comfortable do I feel about the RIT coming to my rescue?

DONALD ABBOTT is retired from the Phoenix (AZ) Fire Department, where he developed and managed the Command Training Center for eight years. For the past four years, he has been coordinator of Project Mayday, for which he has traveled around the country presenting the “Abbottville” training simulator diorama to train emergency responders in emergency incidents and disasters. Abbott retired from a career fire department in Marion County, Indiana, after 24 years of service.