Productivity The Total Cost Approach

FEATURES

MANAGEMENT

Measuring fire service productivity is like fighting a major fire in the middle of a blizzard. It’s difficult but not impossible. And just as the survival of the community depends on the fire department s services, so does the survival of some fire departments depend on the ability to measure their productivity.

In the past, the fire service was considered the community’s “sacred cow” because of the uniqueness of the job. Consequently, fire department productivity was not questioned. However, with today’s economy, most local municipalities are streamlining their operations. Many local officials find that the easiest way to reduce expenditures is to trim agencies straight across the board. This usually results in fewer firefighters in paid departments and inferior equipment in volunteer departments.

Cutbacks in municipal services are often made without considering other viable alternatives or the overall effect when an emergency strikes. Therefore, the onus is on fire department administrators to take measurable steps to insure that their efficiency and effectiveness is not compromised by tightfisted and shortsighted political officials.

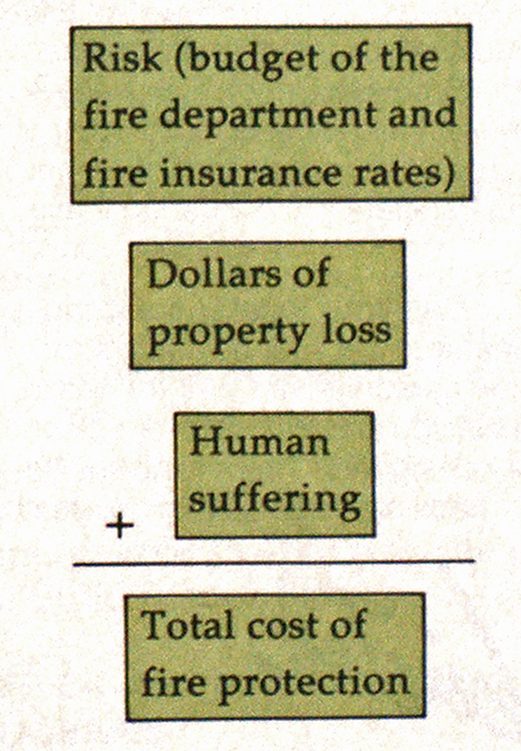

One highly suggested method is to calculate the total cost of fire protection to a community accord ing to the following formula:

In this equation, the risk and dollar values can be accurately measured while the human suffering component needs to be projected. Human suffering can take many shapes: unemployment caused by a business that never reopens after a fire; hospital costs of civilians and firefighters injured due to inadequately manned firefighting crews; and many more.

Objectively, a fire chief cannot resolve all aspects of this total cost equation immediately, but he can use it as a guide to channeling productivity measures and studies.

As with the establishment of any new program, there are prescribed steps that will lead to a systematic analysis of its feasibility, and productivity is no exception:

- Step 1—Is there a NEED to increase fire service productivity?

- Step 2—Is there a COMMITMENT to the productivity plan?

- Step 3—Is there a MEANS TO MEASURE the changes?

- Step 4—Is there a MEANS TO CARRY OUT the program?

- Step 5—Are there FEASIBLE PROGRAMS?

STEP 1—Is there a NEED to increase fire service productivity?

The need for increased fire service productivity is obvious in every town and city where fire department resources have been slashed and the community continues to grow, rebuild, or deteriorate. It is impossible to provide the same quality fire protection with a reduced budget unless productivity is increased.

A common problem when discussing the need for productivity measures is the very definition of this word. To a firefighter, the word itself sets off a negative reaction because productivity connotes an abundance of work. To a company officer, it brings thoughts of increased paperwork. To a labor leader, it is aligned with layoffs. To elected officials, it refers to more efficient and effective operations that will lower operating costs. To a taxpayer, it brings illusions of more services for less taxes. To an entrepreneur, it is a ratio between inputs used to produce and outputs of a product or service.

Therefore, the initial problem in determining whether there is a need for increased productivity is to define the word in a way that is acceptable to all parties, including elected officials who dictate budgets; top level fire department managers who formulate departmental policies; and labor leaders who influence the attitudes of a fire department’s greatest asset, the firefighter. Once these parties can create a mutually acceptable definition of the fire service’s mission and what the term fire service productivity means for their community, then the question of whether productivity needs to be increased can be addressed.

STEP 2—Is there a COMMITMENT to the productivity plan?

Leadership must emanate from the top of the fire service organization with support coming from labor leaders.

The goal of nearly every fire department’s productivity program is to provide the best quality fire protection to the community. The indirect benefit of such a program is a highly motivated department.

It is essential right from the start that the upper echelons of the fire department hierarchy control the productivity programs and communicate to the entire membership that increasing productivity will not be a “this year” program. Productivity must cover the entire department, not just isolated units or personnel. Once this message is clear, the top administrator has two options: First, he can follow the traditional approach of augmenting activities to eliminate standby time. I disagree with this method because unless properly and tactfully instituted, it has limited effects. Certainly proficiency in the use of apparatus and equipment as well as knowledge of the community increases with practice, but firefighter development is restricted because morale can be shattered.

The preferable approach is to intertwine training with an environment that is receptive to the firefighters’ needs and wants. This method can be traced to Abraham Maslow’s theory on motivation.* Once a firefighter receives his basic training on fireground strategy and equipment, he feels that his need to be accepted by his peers will be satisfied. However, his human drives as a person in the community are just beginning. It is the responsibility of the top man in the department to cultivate this drive and allow the firefighter to reach for the highest level of personal motivation (self actualization) by being important to the people of the community.

Since motivation is an inner force, the fire administrator can only create the atmosphere in which the firefighter can develop. It is then up to the individual to find satisfaction within the system of worthwhile community-oriented programs.

STEP 3—Is there a MEANS TO MEASURE the changes?

Fire service productivity is difficult to gauge because there are few tangible items that can be accurately measured. Remember that fire service productivity is concerned with lowering the total cost of fire protection, not with specific activities. Productivity is not a case of working harder but being more effective. Therefore, measuring productivity must be directly related to the effectiveness of performing specific functions as they relate to the total cost equation.

• According to Abraham Maslow’s theory on the hierarchy of needs, man’s basic needs are for food and shelter. Once these are satisfied, man’s secondary need is to have a feeling of security in his job. The third level is man’s desire to be recognized and socially accepted by his peers and the people in the community. The next need is self-esteem, which includes attaining the approval of one’s superiors. The fifth and highest level in the hierarchy of needs is that of self actualization which, simply put, is feeling good about what you do.

One ideal but impossible example of measuring productivity changes would be to determine the exact number of fires that were prevented by our increased efforts. However, this cannot be accomplished because the chemical reaction never took place.

A more practical means of measuring productivity is to collect appropriate data. If citizens’ safety is the primary concern, then programs should be developed to measure effects of public education and fire prevention activities. If lowering the fire department budget is the prevailing philosophy, then emergency medical services and manning levels on fire apparatus need to be measured and analyzed. If lowering fire insurance rates is a priority, then the grading schedule and building construction codes need to be researched.

According to the National Commission on Productivity, the conventional methods of collecting data to measure programs are:

- Cost data

- Workload

- Quantity.

The cost data technique is commonly done by setting up a formal budget. This system will indicate total expenditures to implement a certain program. All programs will have some cost, but some programs can offset these increases with a decrease in the total cost of fire protection to the community. This type of data is useful in selecting programs that are within an administrator’s financial control. In career departments, the manning level is usually determined by this method because the human resource accounts for nearly 90% of a fire department’s budget. Other useful cost data would be allotments for new equipment, apparatus, and contractual concessions.

The workload method is normally expressed in a ratio form. Many industrial productivity studies have focused on this type of data because it provides valuable insight into cost efficiency. The automobile industry used this means of data collection when introducing robotics in the assembly line. Commonly used workload measures in the fire service are: cost per response by each unit, dollars of property loss per fire, number of firefighters per population. It is obvious that each of these single value denominators are important but could be very deceiving in terms of the total cost.

The quantity method is used to quantify general inputs that contribute to the entire system. This deals with the number of programs that support the mission of the fire department. Often this method is used in gathering controllable information such as response times, fire station locations, hydrant flows, and energy costs.

It must be remembered that, individually, each of these programs can be misleading. Collectively, however, they are the means to plan and measure your productivity program.

STEP 4—Is there the MEANS TO CARRY OUT the program?

A fire department that expects to increase its productivity must adopt a participative style of management (see “Is Your Department Ready for Participative Management?” in this issue). This is a harsh system because it requires a total commitment to the organization by all members. It ignores political and social favoritism and focuses on the firefighters’ strengths and develops their weaknesses.

Within this system, high level management must continually solicit and create programs that will lower the total cost of fire protection by being aware of the community’s needs and not only react to past catastrophes. Likewise, individual company supervisors must realize that their local districts are dynamic entities. They are always changing. Therefore, each supervisor and firefighter must consistently look for new approaches and ideas for both fire prevention and suppression while being held accountable for carrying out programs geared to lowering the total cost in their specific area.

STEP 5—Are there FEASIBLE PROGRAMS?

Today, most fire administrators still have the flexibility in their community to institute worthwhile and creative programs. Tomorrow, this may not be possible. Budget control may be given to an outside agency that equates fire service productivity to time motion studies. Already, some civilian personnel officers are calling fire station bunks an anachronism. These individuals do not understand the correlation between firefighters’ attitudes and productivity. We must not forget that productivity is increased when the total cost is decreased. The job of every fire department administrator is to insure that all programs are measurable so that progress can be documented and charted.

Just as the survival of the community depends on the fire department’s services, so does the survival of some fire departments depend on the ability to measure their productivity.

Experience has found that programs specifically geared to combating fires are readily accepted by the firefighters because their professional image is not compromised. However, those programs that infringe on other municipal agencies are usually rejected.

The possibilities for productivity programs are virtually limitless, but they must be carefully planned and frequently monitored. Pilot programs should be encouraged. Some communities may choose to start up a productivity program in fireground effectiveness by analyzing the effects of manning levels on hose stretching, ladder placement, efficient offensive fire attacks, and property conservation. An objective fireground commander may have to re-evaluate his strategy and tactics when faced with manpower shortages.

Other communities may increase productivity via additional fire prevention activities, public education, and fire inspections, all of which are worthwhile and measurable.

A public education program could utilize each firefighting unit. Members could begin by speaking at community gatherings on the protection, cost, and ease of installation of smoke detectors. Fire investigators could target onto crime watch groups and explain the patterns and rationale of firesetters. Emergency medical personnel could be used to inform the public of the department’s capabilities and problems caused by a lack of manpower and equipment, and explain their inability to always be available because of a heavy response rate to many non-life-threatening situations. These educational programs can be measured in the short run by questionnaires sent to survivors of incidents. These questionnaires could focus on specific actions civilians took to escape or minimize an incident and how they acquired the knowledge to do this.

Another productivity program is quality fire inspections. Each company would conduct fire inspections in their local districts. This activity would assist the firefighters in pre-incident planning while helping individuals of the community reduce fire hazards caused by ignorance or carelessness. Quality would be measured by keeping accurate records on the buildings inspected and those having accidental fires. An incidental benefit of these inspections would be the perception of a responsive fire force that could deter many deliberate firesetters.

Conclusion

In conclusion, productivity can take many forms. It can be as simple as an administrator turning his desk away from a doorway so that passersby will not be a constant distraction, or as sophisticated as trying to project the actual number of fires prevented by specific programs.

Today’s fire chief has many options; but, the goal is to lower the total fire protection cost. Fortunately, this can be achieved in those progressive departments that afford the firefighters significant and attainable challenges on a recurring basis to fill those long gaps between real emergencies.