By FRANCIS CALIFANO

It has been a quiet and relatively slow tour. There are two more hours to go on the back end of an 11 p.m.-7 a.m. graveyard shift. It is sometimes hard to work a slow overnight tour and stay sharp. Dispatch breaks the monotony with a “Delta” call for an unconscious/unresponsive male at a nursing home. You snap alert, dust the cobwebs off your partner, start the rig, and hit the lights and sirens. You weave your way through the early dawn traffic. As you approach a major four-lane intersection, it is gridlocked with traffic. You slow down, cross in to oncoming traffic, and take the first lane with caution. Then the second; you look left, right, and left once more. You move to take the next lane. The driver of a truck to your right yields to your approach. Then, seemingly out of nowhere, a car appears from behind the stopped truck. You brace for the impending crash. Harm done.

“Primum non nocere—first, do no harm” is from the Hippocratic Oath taken by physicians and other medical professionals. The basis of medical decision making on a course of treatment is premised on improving a patient’s condition, never worsening it. “Providing health care requires a constant assessment of the impact of certain interventions on patient outcome while balancing that with the risks associated with the intervention. The primary role of emergency medical services (EMS) providers and agencies is to deliver health care, often for medical emergencies, and weighing the risks and benefits of all aspects of delivering care—including the risks and benefits of the treatment of lights and siren (L&S) use—should be part of this practice of medicine.”1

In the course of administering medications, we are taught to adhere to the principle of “5 Rights”—right patient, right drug, right dose, right route, and right time. Should the same principle be applied to the use of L&S? Would (should) the use of L&S be considered part of our course of treatment?

The Law

The use of L&S during emergency medical response and transport has long been hotly debated. When is their use warranted? Does a life-or-death situation, actual or perceived, justify the use of L&S? Each state has its own laws defining what constitutes an authorized emergency vehicle (AEV) and when the use of L&S is warranted. In general, these laws describe the conditions in which an AEV may engage in emergency operations. New York State Vehicle and Traffic Laws (VTL), for example, outline the following2:

- Section 101. Authorized emergency vehicle. “Every ambulance, police vehicle, fire vehicle, civil emergency vehicle, emergency ambulance service vehicle, environmental response vehicle, sanitation patrol vehicle, hazardous materials vehicle, and ordnance disposal vehicle of the armed services of the United States.”

- Section 1104. Authorized emergency vehicles:

- “The driver of an authorized emergency vehicle, when involved in an emergency operation, may exercise the privileges set forth in this section, but subject to the condition herein stated.”

- “The driver of an authorized emergency vehicle may:

- Stop, stand, or park irrespective of the provisions of this title;

- Proceed past a steady red signal, a flashing red signal or a stop sign, but only after slowing down as may be necessary for safe operation;

- Exceed the maximum speed limits so long as he does not endanger life or property;

- Disregard regulations governing directions of movement or turning in specified directions.”

The aforementioned privileges are granted, most often, only with the use of lights and sirens.

- “Except for an authorized emergency vehicle operated as a police vehicle, the exemptions herein granted to an authorized emergency vehicle shall apply only when audible signals (siren) are sounded from any said vehicle while in motion by bell, horn siren, electronic device, or exhaust whistle as may be reasonably necessary, and when the vehicle is equipped with at least one lighted lamp (lights) so that from any direction, under normal atmospheric conditions from a distance of five hundred feet from such vehicle, at least one red light will be displayed and visible.”

- “The foregoing provisions shall not relieve the driver of an authorized emergency vehicle from the duty to drive with due regard for the safety of all persons, nor shall such provisions protect the driver from the consequences of his reckless disregard for the safety of others.”

New York’s VTL grants these privileges with some caveats; the following is a significant one:

“With Due Regard”

“With due regard” is a term with which all AEV operators should be familiar. The Law Dictionary defines it as “to give a fair consideration to and give sufficient attention to all of the facts.”3

Due regard for the safety of all persons requires some further legal wording to clarify its meaning. In the case of an authorized AEV operator’s failure to act with due regard, the conditions in which one failed to do so would have to be judged. This is often done by outlining the condition and circumstances in which an act occurred. Given the same conditions, would a “prudent and just” person act in the same way? A prudent act is an action that is wise under existing circumstances. “Just” means based on or behaving according to what is morally right and fair. Having said this, would a prudent and just person drive an AEV into a controlled intersection in opposition to such controls—i.e., a red traffic signal? The answer logically is “No.”

Know the Rules

How well do the operators of AEVs in your department know the rules or, more appropriately, the laws regarding AEV operations and the use of L&S? A North Carolina survey that tested EMS provider knowledge of state vehicle laws for ambulances revealed a median score of 1 on a 5-point exam.4

Most agencies have policies and procedures or standard operating guidelines (SOGs) outlining emergency response and the use of L&S. SOGs should address the following:

Training. Agencies should require all AEV operators to complete initial and ongoing training. This should include training on state and local vehicle and traffic laws pertaining to AEV operations and the use of L&S. AEV operator training should include knowledge of the limitations and safe use of L&S.

Right-of-Way. AEV operators must understand what constitutes “right-of-way.” It refers to the right of one vehicle or pedestrian to proceed in a lawful manner in preference to another vehicle or pedestrian approaching under such circumstances of direction, speed, and proximity as to give rise to danger of collision unless one grants precedence to the other. (New York State, Vehicle and Traffic Law–Sec. § 139). “Right-of-way” must be granted and never assumed. L&S only ask for the “right-of-way.” It must be granted or yielded by the other person. One way to ensure that the other person is yielding the right-of-way is to make eye contact with that person.

Figure l. Vehicle Soundproofing and Distractions Interfere with Drivers Hearing Sirens

An ambulance moving at 25 miles per hour (mph) is traveling @ 36 feet/second and will cover 280 feet in 7.77 seconds.

Seen and Not Heard or Heard and Not Seen

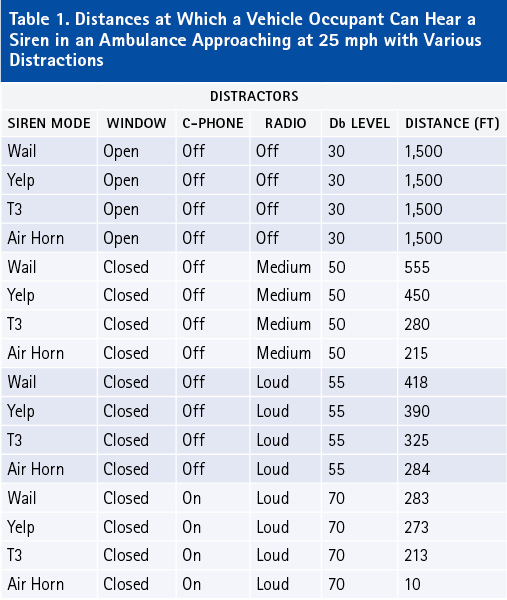

How effective are the lights and sirens on your AEVs? What combination works best in alerting others, both pedestrians and motorists, of your approach? Most automobiles today have very good soundproofing. Couple that with other factors such as windows rolled up, radio on, and other distractors, and it is not surprising how ineffective sirens are. A recent New Jersey study sought to determine distances at which a driver can hear various type of sirens under varying conditions.

Research has shown that sirens may not be as effective as many AEV operators believe them to be. Sirens may be giving operators a false sense of security. Despite the different siren tones (wail, yelp, hi-low, or air horn), their ability to gain a driver’s or pedestrian’s attention is limited and dependent on many varying conditions. EMS agencies and AEV drivers should consider the following:

- Sirens only “request” the right-of-way, which should never be assumed.

- There are limits to the siren’s ability to be heard under given conditions.

- Always use sirens in combination with warning lights.

- Wail and yelp are the most effective siren sounds; hi-low and air are the least effective.

- Educate AEV operators on the effectiveness of sirens as related to speed and travel distances.

All operators should understand the effectiveness and limitation of AEV sirens. Speed, distance, and reaction times can lead to operators “out-driving the siren.”

The purpose of emergency lighting is to attract the attention of drivers and pedestrians to a responding AEV. In general, EMS vehicles use red flashing or rotating lights as a primary warning device. Emergency lighting is used to make the vehicle more conspicuous while moving or stationary. AEVs are often heard before they are seen. Many studies have been conducted on which type of siren is most effective; comparably fewer studies have been conducted on the most effective emergency lighting.

Myths, Hearsay, and Other Perceptions

Much of what is perceived as normal practice for EMS response has been part of a long history of the “We have always done it that way” mentality. “As with many aspects of providing health care, including EMS, the traditional use of some interventions has persisted based on the dogma and inertia of past practice, rather than objective evidence for effectiveness or better outcomes.”6 Following are some of the “myths” regarding the use of L&S:

- Response time: It saves time.

- Medical emergency: Every call is an emergency until proven otherwise. We don’t know until we get there, and we can’t predict what may happen during transport. Therefore, octane and tinnitus trauma are the best medicine.

- Expectations: The public expects us to arrive in a hail of sirens and a blaze of lights.

- Media: Television, print media, and broadcast news portray a certain image.

- Insurance: Our insurer requires it.

- Membership: Our membership will be affected if we cannot allow our “adrenaline addicts” their fair due.

The use of L&S is a cultural issue; we need to change culture to effect a lasting change in this practice.

View L&S as “Patient Therapy”

As with any other form of medical treatment, the use of ambulance L&S while responding to or transporting a patient should be viewed as therapy that will benefit the patient’s outcome. However, this is true only if operators use L&S according to the law and use safe driving practices. You can provide therapy only if you arrive safely and in a timely manner. Let’s look at some of the statistics pertaining to AEVs that address some of the topics we have been discussing.

- The National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA) estimates that 4,500 ambulance crashes result in 33 deaths annually.7 About 25 percent of fatalities involve patients or EMS providers in the ambulance; the remaining deaths were pedestrians, bystanders, or occupants of other vehicles.

- EMS providers die at a greater rate (9.6 per 100,000) than police officers (6.1) or firefighters (5.7).

- Rear occupants are 2.7 times more likely to be killed in an ambulance crash.

- Three or more injuries result from 84 percent of ambulance crashes.

- Greater than 70 percent of ambulance crashes occur at intersections.

- Multiple studies reveal a minimal decrease in transit time with L&S use, with an average of 1.7 to 3.6 minutes saved.8

- In greater than 90 percent of patients, there is no improved outcome from L&S use.

- Most EMS agencies use L&S for 80 percent of 911 calls.9

- One retrospective study found that only 5 percent of patients benefit from the time saved by L&S.10

Based on the compelling evidence, the use of L&S during response and transport needs to be undertaken prudently, with common sense being the determining factor. L&S use should become the exception and not the norm. Effective training should be implemented to instruct AEV operators of all aspects of L&S use, including the legal, physical, and ethical factors involved. Use strict enforcement of SOGs in aiding AEV operators to decide if they should run hot. The use of L&S is a cultural issue; we need to change culture to effect a lasting change in this practice. “This is the way we have always done it” doesn’t hold merit in the face of science.

References

1. U. S. Department of Transportation National Highway Traffic Safety Administration [NHTSA], Office of Emergency Medical Services (EMS) Lights and Siren Use by Emergency Medical Services (EMS): Above All Do No Harm; Douglas F. Kupas, MD, EMT-P, FAEMS, FACEP, May 2017, page 5.

2. New York State Vehicle and Traffic Law: http://public.leginfo.state.ny.us/lawssrch.cgi?NVLWO.

3. https://thelawdictionary.org/due-regard/” title=”DUE REGARD”>DUE REGARD</a>.

4. NHTSA, Lights and Siren Use, May 2017, page 33.

5. Ibid., page 28.

6. Ibid., page 7.

7. Smith N. A national perspective on ambulance crashes and safety. EMS World. 2015;44(9):91-94.

8. Dami F, Pasquier M, Carron PN. Use of lights and siren: is there room for improvement? Eur J Emerg Med. 2014;21(1):52-56.

9. [NHTSA, Office of EMS Lights and Siren Use by EMS: Above All Do No Harm, page 37.

10. O’Brien DJ, Price TG, Adams P. “The effectiveness of lights and siren use during ambulance transport by paramedics,” Prehosp Emerg Care. 1999;3(2):127-130.

FRANCIS CALIFANO, BS, EMT-P, CHSP, is an emergency management coordinator for Northwell Health in Manhasset, New York. He is a 40-year member of Rescue Hook & Ladder Co. #1 in Roslyn, New York. He is a company safety officer and has served as captain of EMS. He has a bachelor of science degree in community services/emergency management from State University of New York—Empire State College. Califano has been a speaker at the Fire Department Instructors Conference International as well as at other national conferences. He is a certified hazardous materials specialist and a certified healthcare safety professional.