Out from Under a Cloud

Features

INCIDENT REPORT

A chlorine leak at a water filter plant in Tennessee forced the evacuation of more than 4,000 people. Disaster planning kept it orderly.

The residents of Morristown, a city of 20,000 in northeastern A Tennessee, awoke on the morning of September 2 last year and saw a dense fog covering a large part of the west end of town. It wasn’t the familiar, early morning fog that it seemed, but a cloud of chlorine caused by a leak in a pair of one-ton tanks connected together through a manifold at the Morristown Water Filter Plant.

Before the leak was capped, 2,400 to 3,000 pounds of the gas would escape, creating a cloud 5 miles long, 1 mile wide, and 30 feet thick. The cloud would force the evacuation of 4,000 people from their homes and 131 patients from a nursing home, close 3 schools, generate a water shortage, and require the cooperation of 40 agencies to handle the resulting problems. A disaster management plan and the initial decisions at the scene made this potentially catastrophic situation a smoothly run incident.

(Photos by Chuck Hale)

At 4:50 a.m., an alarm signaled a water department employee that chlorine—which the plant uses to kill bacteria in the water—was present in the atmosphere. Following procedures, he called his supervisors at their homes. Then, without wearing breathing protection, he entered the room to try to stop the leak. The concentrated gas almost overcame him and, choking, he went outside to wait for help.

One of the supervisors arrived and helped the employee to safety. When a technician arrived at 5:05 a.m., gas was seeping from the doors and was thick on the ground. Seeing no signs of the first two men, the technician feared that both were injured or dead. He entered the room to attempt a rescue. Without breathing protection, he, like the first employee, was choked by the chlorine gas and driven outside, where the supervisor found him.

When the technician recovered enough to drive, he transported the other injured man and himself to a local hospital. (Both men suffered respiratory irritation that would keep them in the hospital a couple of days, but no permanent damage.) The supervisor went to a “safe” phone—in a guard shack away from the leak site—and called 911 for assistance.

The Morristown Fire Department, a career department with 48 members, received the alarm at 5:07 a.m. and responded with two engine companies, a ladder company, and a battalion chief. The cloud was advancing south, and one of the engines was ordered to stop traffic from that direction.

The water plant supervisor advised the firefighters that the leak could be stopped by shutting off the valve. A lieutenant and two firefighters, wearing turnouts and self-contained breathing apparatus, entered the building. The battalion chief gave them five minutes to effect shutdown; other responders stood by as back-up.

The cloud was now 2 feet thick on the ground and extended 200 feet from the building.

The entry team found that the leak appeared to be coming from the tank itself and not the valve. The chlorine, in liquid form but rapidly changing to gas, was escaping in a straight jet that extended about two feet before dropping to the floor. Lacking the equipment to cap the leak, the team withdrew—but not before two of the members suffered chemical burns to the groin and thighs. Outside the building, they were hosed down, but to no avail. Both were eventually transported to the hospital for treatment and kept there overnight.

The gas cloud was spreading rapidly, and all units were withdrawn one quarter mile away at 5:15 a.m. A temporary command post was set up there, and the fire chief, deputy chief, and county Emergency Management Agency (EMA) director were notified of the nature of the incident and the location of the command post. All this was dictated by the fire department’s preincident plans.

Chlorine in Brief

With its many industrial uses, chlorine is a common chemical in many communities.

As a gas, chlorine is yellowishgreen. Nearly 2½ times heavier than air, it hugs the ground, seeking low areas. Its boiling point, – 30° F, causes it to readily vaporize in air. The gas is 457 times more voluminous than the liquid.

Chlorine is highly reactive, possessing chemical properties that classify it as an oxidizer, a corrosive, an irritant, and a toxic substance. Exposure will damage the skin and eyes. Inhalation will result in damage to the respiratory tract, and pulmonary edema can result in cases of severe exposure. Exposure victims should be stripped of clothing and washed with large amounts of water. Medical attention should be sought immediately.

Emergency response personnel should be protected from all contact with chlorine. Positivepressure, self-contained breathing apparatus is a must. Protective clothing should be made of polyvinyl chloride, chlorinated polyethylene, Viton, or neoprene.

For more detailed information, see Frank L. Fire’s article, “Chlorine,” in the July 1986 issue of Fire Engineering.

Since the water plant is located in a high-density residential area, the firefighters and police on the scene began to evacuate the homes that were in imminent danger. Another engine company was called to aid in the door-to-door notification.

Command personnel notified the Tennessee Emergency Management Agency (TEMA) in Nashville. The chief and deputy chief determined that available personnel and equipment wouldn’t be able to contain the leak, so responders would follow a defensive strategy until aid arrived.

The command post was moved one mile south to higher ground upwind from the leak site, and the order to evacuate en masse was given. The evacuation zone was extended to a half-mile radius. Police and fire units went into the affected neighborhoods and used sirens and air horns to awaken residents. Instructions were given on public address systems and door to door. The North Hamblen County Volunteer Fire Department was asked to provide mutual aid to secure its area adjacent to the plant. The Red Cross and the Hamblen County school system were asked to open shelters to house the evacuees.

Chlorine has a specific gravity of 2.45 [see “Chlorine in Brief” at left], and the winds were calm and the humidity high—so the cloud held together in the valley where the water plant is located. This bought time for the evacuators and kept the evacuees from panicking.

At 6 a.m., all off-duty firefighters and police officers were recalled to assist in what was becoming a mass exodus from the leak area. East and West High Schools opened as shelters. City employees cordoned off the vacated areas as they were confirmed clear.

By 6:30, the Emergency Medical Services Division for the Eastern Region of the state Health and Environment Department had been notified, and its director advised that he would respond to coordinate the medical operations. Both hospitals in town were told to delay surgery, dialysis, and other medical procedures. The Morristown Airport was asked to give weather updates.

A TEMA technician arrived, but because his unit had only recently been activated, he didn’t yet have the resources to cap the leak. So the officials in the command post decided to extend the evacuation zone yet again, to three miles north and south of the plant, and to wait until the cloud dissipated before trying to enter the plant. Units from the West, East, and South Hamblen County Volunteer Fire Departments were called to help with evacuation and with traffic control, which was beginning to be a problem. School officials closed three elementary schools in the path of the cloud, which was now 4 miles long, 1 mile wide, and 30 feet thick; in the thickest parts, visibility was down to 100 feet.

The scale of operations dictated a larger site for the command post, which was now within 100 feet of the edges of the cloud. The Country Club of Morristown, on a high ridge 1½ miles from the plant, was chosen for this. The large parking lot provided space for staging, and command personnel could be insulated from distractions. Phones were available on site, which would help make up for a lack of fire department mobile communications that existed because a vehicle being fitted as a command van wasn’t yet out of the shop. The mayor, who was also an evacuee, and a fire department lieutenant were designated as public information officers.

Water officials feared that the chlorine would corrode electrical contacts and relays, shorting out their equipment so that all plant operations would occur at once instead of in sequence. If that happened, untreated water would be released. So at 7 a.m., officials cut the power to the area. Because it was later discovered that corrosion and shorting had already started a large fire in the plant’s transformer room, this was a prudent decision. However, cutting the power killed the transmitter for radio station WCRK. This would compound a communication problem later in the morning.

It was now 7:30. More than 4,000 people had been moved to safety. The biggest problem now was the Life-Care Nursing Center, a 161bed facility with 131 patients, which was directly in the path of the cloud.

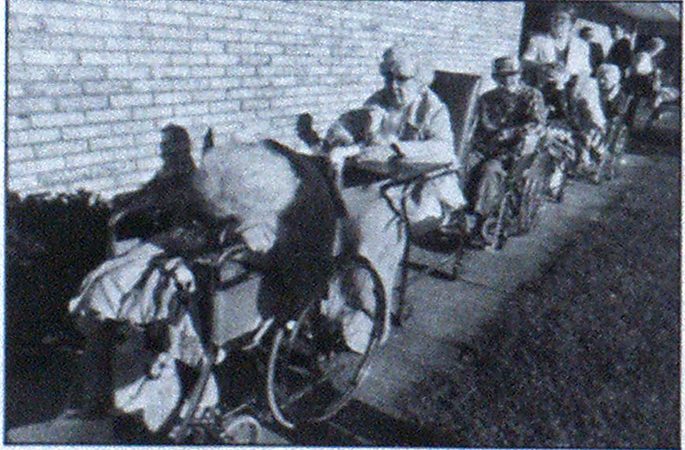

Fire officials advised its administrator to shut down the heating, ventilation, and air conditioning systems, close the outside vents, and prepare to evacuate. Patients were categorized as ambulatory, wheelchair, or bedridden to assess how much and what kind of transportation would be needed. Once grouped, the patients were moved to three different staging areas.

Evacuation

The EMS director volunteered to handle the evacuation. He coordinated the activities of eight area ambulance services, funeral home directors who lent hearses, and other agencies. He also called the state area vocational schools to have them send their nursing students to assist. The school superintendent provided buses and lift vans for wheelchair patients.

The evacuation began at 8:30. Bedridden patients were taken to hospitals and nursing homes in Jefferson County, 15 miles away. The other patients went to West High School. Local ham radio operators were summoned to the Life-Care Center and West High to set up communications between the two sites.

Morristown’s two remaining radio stations, WAZI and WMTN, located near the nursing home, were cleared at the same time. With WCRK already off the air, local residents were without information about the crisis. In the 45 minutes it took WAZI and WMTN to set up remote broadcast facilities at West High, Knoxville radio stations made some erroneous reports that led people to believe it was all right to return home. Some confusion resulted, but command post officials quickly informed the Knoxville stations of their errors.

As the patients arrived at West High, the principal asked the Key Club, a service club at the school, to help them. What resulted was one of the highlights of the incident. As the rest of the student body learned what was happening, more students came to help. They unloaded, reassured, and calmed the patients. More than 600 students at West High worked in shifts to feed, care for, and comfort the elderly. Over at East High, the students were engaged in the same type of activities. Their assistance helped make a smooth transition for the patients and drastically cut the evacuation time. It was complete within an hour.

Surrounding communities were also living up to the Tennessee nickname of the “Volunteer State.” The Knoxville Fire Department sent air packs and spare bottles; Rural-Metro Corp. sent emergency medical technicians and paramedics; Johnson City sent a haz-mat team. Offers of help flooded in from industries and various state and federal agencies.

Reserve and volunteer apparatus moved to cover city fire stations in the affected areas. Tankers were stationed to supply water for firefighting if the reservoirs were emptied while the filter plant was shut down. Water officials shut down car washes and laundries and asked industry to cut back on water usage.

As the life hazard was removed, the hazardous-materials operation geared up. TEMA’s regional director had arrived earlier, and the command post personnel were divided into two groups: one for evacuation and security, one for haz-mat control.

Because TEMA wasn’t yet in a position to cap the leak, back-up plans called for BASF Fibers Inc. to be notified. BASF, a multinational corporation, manufactures chemicals and textiles at a plant near Morristown. The plant has a trained and equipped response team with a chemist as chairman. He was contacted at about 8:30, and the team reported to the command post 15 minutes later.

Van Waters and Rogers Inc., the chlorine supplier, was contacted at its Chattanooga headquarters at the same time. That company also dispatched a team, but it would have a 2’/2-hour trip to make.

The cloud had reached its maximum extension of 5 miles in length, 1 mile wide, and 10 feet high. As the heat of the sun raised the cloud and the breeze dissipated it, conditions improved.

BASF’s team was ready to move down to the water plant by 9:30. An engine company set up hose lines for decontamination and to serve as back-up for the team. Two technicians, wearing encapsulated suits with SCBA, entered the chlorine room. They saw that the escaping gas had condensed and frozen moisture from the air into a “snowball” the size of a softball; this had stopped the leak temporarily.

The team made three entries to observe conditions and to lay out the capping device—Device 12 from the Chlorine Institute’s B kit. The B kit is designed to handle leaks in one-ton tanks; Device 12 consists of a hood with a yoke, suction cup, and gasket.

Between entries, the team members put the device together in a dry run and changed their SCBA air supplies. They also had their suits and other equipment decontaminated to reduce the respiratory discomforts caused by the chlorine residue. Preconnect lines were used for the decontamination washdown. The rinsing and changing of air bottles caused considerable delay, and the three entries took more than an hour.

During this time, the remaining fire in the adjacent transformer room was extinguished with dry chemicals after having been allowed to nearly burn itself out.

The BASF technicians were now ready to cap the leak. When they removed the ice from around the valve, then removed the valve yoke and adapter, liquid chlorine began escaping from the vessel. As it turned to gas, the temperature around the tank dropped to less than 0° F. One of the technicians, on his knees working on the cap, was engulfed in the gas, and his suit froze to the floor. His companion pulled him free, but in the process, the kneeling man’s suit ripped, exposing him to a concentrated dose of the gas. Both men’s face masks froze over, obscuring their vision.

Back-up teams moved to them as they stumbled to the light, and the technician in the ripped suit was stripped and hosed down. Because he was wearing an SCBA, his injuries were limited to minor frostbite of the fingers and skin irritations. After a doctor checked him out, he got another suit. He and the other technician, who was uninjured, reentered and applied Device 12 at 11:30.

At about noon, the Van Waters and Rogers team members arrived, removed the temporary cap, and applied their own device, which would provide more stability for transportation.

Lessons Learned

ieinforced:

t aster plans pay off. They provide for efficient emergency nagement, and should list more than one possible solution for each c, erational objective.

Industry should be looked to as a resource for response expertise.

The planned use of easily mobilized civilian groups to work with the evacuees brought positive and efficient results.

Reexamined:

The command post location should be marked for easy identification. Essential personnel should also be more conspicuously identified with caps, vests, or the like to enhance the command function, reduce confusion, and increase security.

A command post van and increased mobile communications are essentia..

Organizations providing mutual aid need to communicate on a single radio chat lei.

Public infoimation officers must be kept up to date on developments. Security must be maintained throughout the incident.

Power company and water plant employees repaired the damage; at 12:30, the plant was restarted. Water reservoirs were down to a twohour reserve, and the public was asked to conserve water. Fortunately, the water department operates two community wells for back-up, and the citizens, knowing that, didn’t panic.

At 2:30 in the afternoon, 9 hours after the incident started, the area was declared safe and residents were allowed to return to their homes. By 6:30, the water levels in the reservoirs were declared acceptable, and the water crisis ended.

For the next three days, employees of the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency and the Air and Water Quality Division of the Tennessee Conservation Department monitored the area; they found no permanent damage.

One week after the leak, Van Waters and Rogers hosted a seminar for public safety, water department, and industrial personnel to discuss how to handle problems that might arise in future incidents. And two weeks after the leak, all the agencies involved had an opportunity to participate in a critique.

They recognized that better communications equipment would have helped. More mobile radios and a mobile command van are also needed. It was also pointed out that separate mutual aid channels would have been helpful so a central dispatching point could have been used. During the incident, as many as five different dispatchers—from the fire, police, and sheriff’s departments, the EMA, and the Red Cross—were working on five different channels with little or no coordination among them. This caused some minor delays but could prove serious at a future crisis. The EMA director is expected to introduce Enhanced 911 to the city and county governments for study.

There also has to be some system established so that if all three radio stations are off the air, broadcast capability can be restored quickly.

Another type of communication— public information—requires that the PlOs be kept up to date on what’s happening. In at least one case, a reporter was the first to tell one of the PIOs about a development during the incident.

Command post personnel need to be better identified—by caps, vests, or some other means. In the crowd of people who were there, those in charge became hard to find.

Security needs a closer look for any future mishap. Toward the end of this incident, people from the departments and agencies involved began to drift close to the leak site before it was really safe.

And even though the incident ran smoothly, four people received minor injuries. The filter plant has changed its process so the chlorine can be used as a gas instead of a liquid. This way, the tube attaches to the vapor space portion at the top of the tank. And if a leak develops in the lower portion, where the liquid is, the tank can be turned on its newly installed rollers to put the hole above the liquid. The plant also has just one vessel on line at a time now, so if there’s another leak, it will be a smaller one.

On the plus side, the contingency plans worked. Nearly 4,200 people were moved, including 131 nursing home patients along with their medicines and records, and the 40 agencies involved were coordinated well. The EMA director, who had been in the position for only a month, made sure the proper agencies were aware of what was needed and had the necessary support.

Officials had been unreserved in preincident planning.

Another reason the response went well is that officials had been unreserved in drawing up preincident plans. They imagined worstcase scenarios and wrote in procedures that include at least one alternative in case the preferred action isn’t feasible. As a case in point, we weren’t able to use the TEMA team as planned; BASF was the next alternative. In the same vein,’ plans called for the nursing home patients to be moved to a nearby church facility, but the church was also in the evacuation zone. Removal to the high schools was a viable alternative.

Overall, the situation was handled well. The icing on the cake was the response of the young people at the high schools. Working with the evacuees, they showed that they were willing to help others.