By Robert Lorenz

As I watched the Fire Engineering/ MSA podcast on cardiovascular/carcinogenic exposure risks for firefighters (http://emberly.fireengineering.com/webcasts/2015/06/cardiovascular-and-carcinogenic-hazards-of-modern-firefighting.html), I felt compelled to share my story. Although I have had the unfortunate experience to be able to speak on this subject firsthand, I am fortunate in that I am still around to talk about it.

Incident No. 1

In June 2013, I was a member of the first-arriving company on a wind-driven fire in the overhead of a large three-story apartment complex. My crew’s assignment was to extend an attack line to the third floor, force entry, and locate and extinguish the fire. Once inside, we found the overhead to be heavily involved. I breached the ceiling, pulled a table over, climbed up, and began extinguishment. Because of the construction of the attic space, I had to pull myself up into the attic space. I momentarily displaced my face piece and helmet. Once they were in place again, I began knocking down the fire in all the areas I could access. I noted that the remainder of the fire was behind a wall I could not access from my perch. I dropped back into the kitchen. We moved cabinets so that I could climb up and open up the wall section and knock down the rest of the fire.

This was an aggressive fire attack. If we had not given 110 percent, the fire would have spread throughout the complex. Pulling myself up into the attic space took maximal effort. My heart began beating hard. The breath of smoke I inhaled when my mask was pulled off did not help. I began to feel winded, more than I should have. I began to get pain in my chest and left shoulder blade. The harder I pushed, the worse it got. When the crew that was relieving us arrived, I felt wiped out. I was winded, and my chest ached. We were sent to rehab. I was very restless. I could not sit still and continued to find work to do. I did not feel my usual self for the remainder of the shift.

|

| Photos by author. |

Most of you are thinking that I should have reported it and should have gone to the emergency room (ER), since these were classic heart signs. I was a very fit six-foot, one-inch, 200-pound firefighter.

In August 2009, during the overhaul of a residential fire, I had a similar pain in my left shoulder. I thought I had pulled a muscle. It bothered me all night, and I was working overtime the next day. It got worse throughout the day, and I got a little winded. The crew worked me up, and my 12-lead electrocardiogram (ECG) showed a posterior fascicular block, so I was transported to the ER.

The hospital ran all kinds of tests and told me my heart was as healthy as that of an 18-year-old. My arteries were clear. I subsequently passed my treadmill test and was told it was a muscle strain.

Over the next several years, the pain would return. Occasionally, I would feel very lethargic. Since I was told that my heart and arteries were healthy, I assumed the pain was muscular and that I just needed to train harder and exercise more. Looking back to June 2013, when the problem first surfaced, I would get this very strange feeling in my chest. It was like getting your breath taken away when you jump into ice water. It happened several times the following month; a few times, I got lightheaded.

Incident No. 2

In August 2013, I was conducting a large-scale training exercise for the department. We were using a city block that was going to be demolished. It had been a very busy week between teaching and running calls. I was feeling very off toward the end of the week, so much so that on the last day I commented to my partner that if I had felt the same as I did the day before, I am not sure I would have made it through the shift.

I demonstrated some masonry wall breaching and scaling techniques (photo 1) that I had done all week without difficulty, but this time it wiped me out as if I had climbed a mountain. It was bad enough that I knew I couldn’t finish the shift and that something was definitely wrong.

I violated range rules (getting injured and not telling anyone, for example). I had my partner continue to teach, taking the group into the buildings to discuss interior construction, while I slipped off back to the apparatus. I checked my vitals. I was slightly tachycardic, my blood pressure was okay, and the 4 lead had slightly peaked “T” waves. I assumed I was dehydrated and hot from the long week. I hydrated and peeled off my gear. Ten minutes later, nothing had changed. I hooked myself up to the 12-lead ECG. As I hit “Analyze,” the guys, who had noticed I was AWOL, came looking for me.

The strip printed out. One of them grabbed it before I could and said, “You are going to the ER.” A discussion ensued. I was outranked and outvoted. The strip showed a posterior fascicular block, the same as four years before.

At the Hospital

As is often typical of an ER visit, everything was normalizing by the time I was seen, except that my cardiac enzymes were borderline, which the doctor said could be caused by the exertion. I was a healthy, fit guy with no risk factors. The doctor said he was going to admit me just to be safe and that I would run a nuclear treadmill test in the morning.

Let me start by saying you do not want to spend the night at the hospital with a cardiac diet restriction. I had not eaten all day. So for dinner, I ordered chicken noodle soup. It came with two noodles, a piece of meat, no crackers, and no salt.

In the morning, I smoked the treadmill, but I felt a little winded and had slight chest pain. The doctors said I did well and that everything looked good and that as soon as the images from the nuclear test were back (they inject dye and take pictures immediately after the treadmill), I would be going home. Great, another waste of time! As I was gathering my things to go home, the floor doctor was coming toward my room with another doctor. He was introduced to me as the doctor who would be performing my cardiac catherization.

It went from “All is well and you’re going home” to “It appears you have a major blockage in the back of your heart.” The cardiologist assured me I would feel much better after the procedure, I would be 100 percent, and I would be back to work in several weeks.

As I was lying on the table listening to the doctor as he guided the catheter through my heart, he commented, “That’s odd. Your arteries are big and clean.” I said, “That is good, right?” He said yes, but based on the amount of ischemia visible on the nuclear images, he was expecting to find a major blockage. He then said, “Oh, there is a large aneurysm.” That was not good.

I was then moved to the echocardiogram room, where they got another image of the aneurysm. I was sent back to my room. The nurses were trying to reassure me about getting my chest cracked open the next day. Needless to say, I did not sleep much. I wrote a note to my wife and kids on a paper towel just in case. The next morning, after further review, they decided the aneurysm was smaller than they thought.

I had subsequent tests that only raised more questions. During this period, I kept having that funny feeling in my chest and occasional lightheadedness. I knew if I mentioned the lightheadedness, I would definitely not get cleared back to the line. As the doctors reviewed all the tests, they came across the computed tomography (CT) scan results from 2009. They could see the very beginning of the injury on those films. The doctors missed it at the time.

My left ventricle was now mostly scarred over. In the process of scarring over, it adhered itself to the pericardial sac. The aneurysm formed as a result of pushing myself through what I thought was muscular pain and shortcomings in my conditioning at the apartment fire. The aneurysm started runs of ventricular tachycardia (the funny feeling in my chest), which caused everything to come to a head.

Pulled Off the Line

I was pulled off the line and began working days while the doctors came up with a game plan. They preferred that I would retire. I explained there are several problems with that plan. First and foremost, I love to work and do my job. Second, in our state, the system will far from treat you fairly unless you prefer to live off the system, in which case it will give you a gold card. The immediate problem was that I was at high risk of sudden cardiac death because of the injury. This meant I had to have an implanted defibrillator. This typically is the end of the line for firefighters. The cardiologists will not clear you for duty with the traditional implantable cardioverter defibrillator (ICD) because, among other reasons, it is placed in line with the self-contained breathing apparatus straps, there are fragile wires running into the heart, and the risk of damaging the device in our job is high.

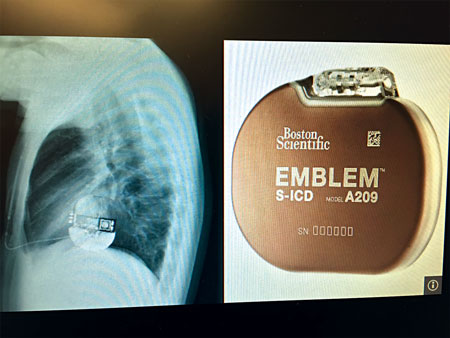

My electrophysiologist fought long and hard to get a device that was considered experimental. It was in Europe for close to a decade and in this country for half that time. It is a rugged device [subcutaneous implantable cardioverter defibrillator (S-ICD)] (photo 2) that is placed under the left arm; no wires go into the heart. It is only a defibrillator. The insurance companies did not want to pay for it (the cost is less than that for the traditional ICD) because it was experimental, even though I would be unemployed if I did not get it. In the meantime, I had to wear an external defibrillator (photo 3), which the firefighters at my house affectionately coined “my bra and purse” for five months.

As bad as things were, I had several things going in my favor. I had excellent, supportive doctors. I was in extremely good physical condition, so my heart was larger and more efficient. Thus, when I injured it and lost that cardiac function, I still had the reserves to function at an acceptable level. I never smoked, I was height-weight proportionate and healthy, and I had no family history. These issues are the same ones our state considers under presumptive language for firefighters:

Revised Code Washington (RCW) 51.32.185 Occupational diseases – Presumption of occupational disease for firefighters – Limitations- Exception – Rules. This presumption of occupational disease may be rebutted by a preponderance of the evidence. Such evidence may include, but is not limited to, use of tobacco products, physical fitness and weight, lifestyle, hereditary factors, and exposure from other employment or non-employment activities.

This is another big reason you owe it to yourself, your family, and your work family to stay fit and healthy. I still had a long road and uphill fight to get cleared back for duty, but I had no plans to go without a fight. If I was going out, it would be on my terms. My biggest fight, it turned out, was getting the injury covered by my insurance.

Labor and Industry Fight

While I was still in the hospital, the state declined to classify my injury as job related. At this point, I had not even been worked up by the cardiologist. Hospital billing, being what it is, had access to my private insurance company and sent it the bills. What happened over the following two years makes following the flow of the Amazon from its source to the ocean appear simple. My insurance paid for some things, Labor and Industry (L&I) paid for a few initial things after a fight, and we set up payments on the others. It took close to two years to get L&I to accept and start paying bills. The irony is that it is clearly delineated in the RCW regarding cardiac injuries for firefighters at work, and L&I still fought it: …. ”there shall exist a prima facie presumption that: (a) Respiratory disease; (b) any heart problems, experienced within seventy-two hours of exposure to smoke, fumes, or toxic substances, or experienced within twenty-four hours of strenuous physical exertion due to firefighting activities; (italics mine) ….

L&I eventually sent me to see its “expert” cardiologist for an exam. It was very apparent when I saw him that he had not read either of the reports and was not familiar with my occupation. Below are several quotes in his report to L&I:

“There is no known connection to physical exertion or to smoke inhalation, or exposure to any environmental toxins that the claimant would be subject to in his employment.”

“His occupation would not increase the likelihood that he would be exposed to any infectious agent.”

According to the state’s expert, firefighters are not exposed to smoke, toxins, or viruses at work, nor are there known connections to physical exertion and heart injuries.

Consulted Attorney

At this point, I went to an attorney. I had spent close to a year dealing with this stupidity. Even then, it was almost another year before things began to get resolved. The State Attorney General’s Office didn’t even agree with its client, L&I; but L&I was insistent on fighting it. The staggering medical bills, the constant worry of whether or not I would have my career, and the continuous battle with the system to get things resolved wore me out. We have to watch videos about workplace bullying put out by L&I; it wants you to understand that bullying can lead to medical problems, but aren’t real medical problems made worse by bureaucratic bullying?

I eventually got myself cleared back to duty, no thanks to the “system.” I have been left with an approximate 20 to 25 percent loss in cardiac output. I am not supposed to “work hard,” lift heavy weights, and participate in endurance sports. The doctors wanted me to retire, but I explained that in our state if you can ask, “Do you want fries with that?” you are considered gainfully employable regardless of your prior occupation.

Cleared for Duty with Conditions

It was imperative that I get cleared for full duty. Since I had been very fit before the loss of my heart function, I still had ample reserves to do the job. I could still pass my treadmill test and perform my essential duties. The doctors were willing to release me on a short leash as long as everything stayed stable. The goal is not to increase the size of the aneurysm, scarring, or loss of cardiac function. Inflammation has been implicated as a significant cause of damage to the human body, including the cardiovascular system.

Inflammation results from all kinds of things, among them stress, hard work, exercise, and lack of sleep. Unfortunately, that is our job description. I live on anti-inflammatories now. I try to adjust my life to minimize and control those potentially damaging factors I can. I live with frequent chest pain; some days are worse than others. I have to be careful of what I tell the doctors so that I do not put them in a bad spot.

Another reason I wanted to make sure I was cleared with my S-ICD for return to duty and, once cleared, show that it could be done is for those who may come after me. The S-ICD may not be the answer for everyone in a similar situation; but, if it is, there is the precedent that it in and of itself is not a career ender.

I have to balance all this to support my family, stay fit, do my job, not let my fellow firefighters down, and fight the insurance companies and the state. I will never know which day may be my last day at work because the doctors changed their minds or I had a bad day at work.

Most firefighters, when they crawl into an overturned SUV to rescue a trapped infant and her mother, would be thinking this is a great job; I am the man holding the spreaders overhead popping the seats out to gain access. I am lying on my back supporting the spreaders with my feet while I pop out the rows of seats thinking, “Man, if my defib fires right now, I am going to drop this 80-pound tool right on my face, and the guys will never let me hear the end of that.”

The doctors say they will never know what exactly I was exposed to at the fire. So now that the injury has stabilized and I have been back online for close to a year, I have to continue to watch what I do and how I do it so I can keep working, watch my kids grow up, and hopefully enjoy retirement when that day comes.

Many things can hurt and kill you on the job. You owe it to yourself to wear your personal protective equipment properly, be in the best physical condition, and stay sharp technically. If we fail at our mission or are hurt or killed, never let it be said that it was because of a lack of training, physical conditioning, or preparation. A cardiac injury is not a cool injury. When you have to take five minutes to explain, it ceases to be cool. When people ask what happened to your eye, you tell them, “It was ripped open.” They get it; it’s cool.

ROBERT LORENZ has been in the fire service since 1998 and is a 15-year veteran of Central Pierce (WA) Fire & Rescue (CPFR). He was a member of the CPFR and Rapid Intervention Team Bag Extrication Teams that competed and placed in regional TERC events in 2005, 2006, and 2007 and competed in the 2006 and 2007 TERC Nationals. He has been an instructor for and competed with the Puyallup Extrication Team since 2006. He is a member of the Pierce County Law Enforcement/Fire Joint Training Consortium, which spearheaded the regional joint training and response to active shooter events for more than a decade as well as other cooperative operational and training objectives. He is an instructor at the local, regional, state, and federal levels for the Puyallup Extrication Team; in forcible entry; and with active shooter rescue teams. He has served as a SWAT medic since 2004. He is also a fusion liaison officer.

Editor’s note: The opinions expressed in this article are those of the author.

Firefighter Cardiac Arrest: Chain of Survival

Firefighting Affects Cardiac System

Firefighter Down: Treating Cardiac Arrest

Fire Engineering Archives