BY ANTHONY AVILLO

Mutual and automatic aid, properly coordinated and used, are critical in creating a safe fireground. Unplanned; uncoordinated; undisciplined; and, therefore, unacceptable mutual-aid operations become nothing more than a line-of-duty injury and fatality delivery system. Nonexistent, ill-maintained, or unenforced mutual-aid policies create a Tower of Babel firefighting condition, which is a by-product of the failure to communicate among those who share mutual aid. Multiple agencies speaking multiple uncoordinated operational languages set the stage for bad things to happen.

Communication is the lifeblood of the fire service. It bombards us from all angles, formally through our own department channels, informally through “the grapevine,” and externally through the continuous barrage of mass media and professional information. It seems we communicate with everyone. Unfortunately, we often fail to communicate with our closest neighbors. Although we regularly use their services, we are often like two (usually more) fire departments passing in the night. Full-contact fire departments communicate, plan, coordinate, train, and evaluate together because they know they will be working together.

Mutual-aid requests, whether an automatic response or a command request, should not be a harbinger of doom regarding control and accountability at the incident. Mutual-aid departments that have prepared together are unlikely to come in with their own competing policies/procedures, ideas, attitudes, and agendas. The late Chief (Ret.) Alan Brunacini of the Phoenix (AZ) Fire Department said, “The only thing worse than no plans is two plans.” Unaddressed and uncommunicated scene expectations and action plans often provide a worst-case scenario for all involved (photo 1).

(1) Well-communicated action plans create a well-coordinated fireground, which is especially critical when using the rare interstate mutual-aid assignment. Although interstate unified command is used for incidents in the Lincoln Tunnel, in the train tunnels under the Hudson River, and on the river itself, this rare mutual-aid response from New York City occurred when four four-alarm fires struck uber-congested Union City, New Jersey, all at one time. (Photos by Ron Jeffers.)

Following is a list of discussion points for fire departments to consider for creating an environment in which mutual aid plays an integral role in positive outcomes.

Create mutual policies that outline scene expectations. As much as written and unilaterally enforced policies, rules and regulations, and standard operating procedures (SOPs) are required for the smooth emergency ground operation of a single department, it is even more critical to foster and promote this “same page” coordination between mutual-aid agencies. Failure to have these control and safety devices in place leads to unsafe situations with even more unsafe solutions and “decisions of the day” by the well-intentioned but unorganized.

Conversely, policies in place that are not enforced are as effective as having no policy. Mutual game plans must be in place, known, and enforced by all in the alliance. Consider operations that are outside the established action plan unacceptable; reinforce this across the participating departments.

Before we merged five fire departments in 1999 to form North Hudson (NJ) Regional Fire & Rescue, the on-duty shift commanders of the old departments would meet every Sunday morning to discuss game-day policies and work out kinks in advance. We explored the operational similarities and differences among our departments before they became an issue. We also would invite the mutual-aid chiefs to our postincident evaluations so they could provide input from their department, which could lead to better coordination and increased safety on the next incident. We also adopted mutual policies on communications, the incident command system (ICS), Mayday and emergency traffic, self-contained breathing apparatus operations, and intercity response. It not only made it easier to work together, but it also made the fireground transition smoother in postregionalization operations.

Maintain a proper span of control. Span-of-control issues often become more difficult when mutual aid arrives because command has more people with whom to contend. If no policy is in place to address span of control, all incoming personnel have no option but to report everything to only one person, the incident commander (IC). Even the best people can get overwhelmed in this situation.

The solution is planning before the incident. Most mutual-aid departments bring chief-level officers with them. They cannot be at the command post (CP) wearing a baseball cap and flip-flops. A mutually created and enforced command structure policy that outlines game-day expectations helps make these “visitors” productive partners in command.

Dividing the emergency ground into manageable parts is the only way to address the multiple-alarm, mutual-aid response and span-of-control issues. This means assigning mutual-aid officers not only as division commanders but also as accountability officers, safety officers, and whatever additional ICS positions must be filled to properly coordinate the incident and keep the span of control manageable. This will not work on the day of the fire if it has not been addressed beforehand. Comprehensive multiagency “hard think” sessions are required in the soft environment to meet these challenges and ensure that game-day activities are reinforced with a solid, cooperative plan of shared vision and mindset (photo 2).

(2) Chief officers from visiting teams must be well-prepped to serve as division commanders. A Jersey City (NJ) Fire Department battalion chief commands his department’s companies and those from North Hudson (NJ) Regional Fire & Rescue in an exposure unit at this multiple alarm in a North Bergen, New Jersey, townhouse complex fire.

Operate under an effective personnel accountability policy. This issue starts at home too. Undisciplined home teams can almost guarantee that undisciplined visiting teams will fail to follow procedures. Why should they? A cooperative mutual policy addressing accountability with a no-nonsense approach toward freelancing will allow the teams coming into the fray to have an accountability plan in mind. Undisciplined accountability policies almost always lead to unsafe firefighting. Solid interagency accountability policies must be created and enforced at all incidents, not just at the “big ones.”

History has shown that if you don’t practice proper procedures at the small incidents, it is virtually impossible to pull it off at the “big ones.” If personnel are not going to follow simple accountability rules, what other rules will they ignore? Policies covering wearing personal protective equipment, mandatory mask rules, communication discipline, and apparatus speed and safety come to mind as additional policies likely to be disregarded.

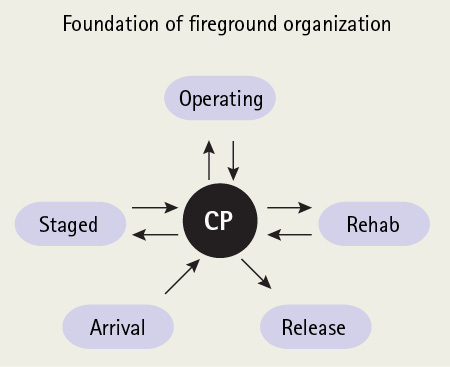

The CP is an organizational manifold. The CP is the operation’s control center. Failure to report to the CP on arrival starts the chain of freelancing. Where that leads to is at the mercy of the fire gods. Apart from the first-arriving companies who will operate as per departmental scene assignment SOPs, all operational status change must go through the CP without exception. There are three operational status assignments: staged, operating, and rehab. Companies and chief officers may not change status assignments without going through the CP. In this way, all fireground strategic movements can be tracked and accounted for. Notice the operational status assignments in the boxes in Figure 1. Notice also that the arrows never go between boxes. The arrows go only back and forth between the CP. That is how it should work. Departmental and mutual-aid policy should address and enforce this critical piece of fireground organization and safety (Figure 1).

Figure 1. The Accountability Model

Solid and mutually understood policy creates accountability right from the start. Other than first-arriving companies with scene-specific, SOP-driven assignments, all companies must report to the command post as a matter of policy. Incident intelligence briefings and subsequent assignments link the coach with the players, strengthening the team.

Keep the rapid intervention crew as a rapid intervention crew (RIC). Failure to adhere to this is all too common on the fireground. Condoning, allowing, and ordering the RIC to engage as a nonRIC player is often a contributing factor at line-of-duty-death (LODD) incidents. How many times does the RIC get pressed into firefighting service, leaving the incident without rapid intervention services for firefighter rescue at the time when it usually is required the most, in the early stages of the operation? RIC officers who are themselves chomping at the bit to go to work and who invite and embrace such action are missing the point of firefighter safety and are a big part of the problem—but not as big a problem as the IC who puts them to work. Keep the RIC as the RIC, and make sure you have enough companies on the response to begin with.

When you know you are understaffed 99 percent of the time, require automatic aid on the initial dispatch for reported fires and target hazards so that if an incident does occur, you can expect a quick escalation. To try to make up this deficiency by assigning the RIC to operational duties is unsafe and unacceptable. Plan, plan, and plan some more. RICs that think fighting fire is more important than their assigned RIC duty often wind up needing a RIC themselves.

(3) Regional live fire training exercises in the Lincoln Tunnel under the Hudson River involve the Fire Department of New York, the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey, and the North Hudson Regional Fire & Rescue.

Invite regular and standardized training between mutual-aid fire departments. If the only time you see your mutual-aid departments is on the emergency ground, do not be surprised by the game-day confusion and frustration. There is no glue between the pieces. When I give classes, I encourage the requesting departments to invite their mutual-aid partners. It is common to find that virtually no training occurs between these departments. The fireground is not the place to find that our languages are incompatible. It is essential not only to train together but also to discuss and plan with those players in the soft environment because they are the ones you will be working with in the hard environment. It allows mutual glitches to be worked out in advance. Glitches on the fireground create time delays and often result in unsafe “fixes and adjustments” for an issue that could have been addressed and solved before the incident occurs (photo 3).

Create mechanisms for effective radio communication. Communication always seems to be the “fall guy” for fire department operational shortcomings, as Brunacini said. Almost all LODD reports identify communication failures as contributing factors, such as undisciplined and excessive radio chatter, failure to assign frequencies, and lack of coordination. Dispatch center consolidation using common communication policies makes a lot of sense in the mutual-aid-rich environment in which most departments operate. The consolidation of dispatch centers in North Hudson paved the way for the eventual regionalization about 10 years later. Going from operating on separate frequencies to eventually operating on the same frequency provided an even stronger ability to work together. Establishing, coordinating, and practicing solid radio policies across mutual-aid departments is an operational function that no organization can fail to enact.

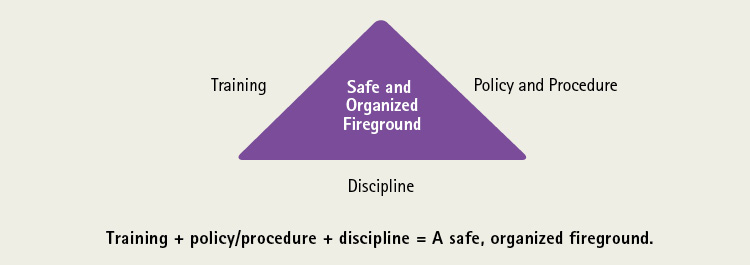

Fire departments that run mutual aid together must realize the benefit of other mutual activities, such as mutual policy/procedure creation/adoption and mutual training. It is their responsibility, on behalf of the communities they serve, to ensure the most effective fire and rescue force possible. Failure to practice together will almost guarantee poor game-day performance. Without these mutual activities, more players brought into the game will further guarantee exponential loss of control. The variable is the human factor (player discipline), which is based on expectations and supported in its purest sense by proper and consistent (and constant) supervision and full contact leadership. The Mutual-Aid Safety Triangle connects the points that create the effective mutual-aid fireground (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Mutual-Aid Safety Triangle

ANTHONY AVILLO retired in 2015 after a 30-year career in the fire service. Avillo was a deputy chief in North Hudson (NJ) Regional Fire & Rescue. He has a BS degree in fire science and a master’s degree in national security studies from New Jersey City University. He is a deputy fire marshal and director of the Monmouth County (NJ) Fire Academy. He is also an adjunct professor at New Jersey City University, teaching fire science. Avillo is a member of the FDIC International advisory board and the editorial advisory board of Fire Engineering. He is co-author of Full Contact Leadership with Ed Flood (PennWell, 2017). He is the author of Fireground Strategies, 3rd edition (Fire Engineering, 2015) and Fireground Strategies Workbooks (Fire Engineering, 2002, 2010, 2016). Avillo has also contributed to both volumes of the Pass It On books by Billy Goldfeder (PennWell, 2015, 2016) and the Tactical Perspectives DVD Series (Fire Engineering, 2011). Avillo co-authored (with Frank Ricci) the Safety and Survival chapter for the Fire Engineering’s Handbook for Firefighter I and II (PennWell, 2018). Avillo issued the DVD Control of Fireground Operations and Forging a Culture of Safety (Fire Engineering, 2016, 2014). He was recipient of the 2012 Fire Engineering/ISFSI George D. Post Fire Instructor of the Year Award.