Part 1

By Phil Jose

The fireground is an inherently complex and dynamic environment. Lessons taken from military special operations can guide our planning, preparation, and execution on the fireground. We seek better execution to achieve our mission: to save lives. This is the first in a series of articles applying concepts developed by Admiral William McRaven, former commander of U.S. Special Operations Command (2011-2014), to fireground operations and fire department culture. The concepts are taken from his doctoral thesis, published as Spec Ops: Case Studies in Special Operations Warfare Theory and Practice (Presidio Press, 1996).

- The Modern Fire Attack

- Reading Smoke and the Transfer of Command Process

- Phil Jose: Teaching the Fire Service: A Question of Engagement

- Fire Instructor Development: Your First Classroom Session

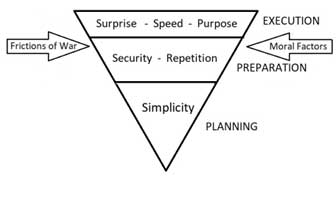

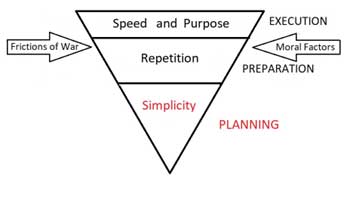

The Thesis

McRaven examined eight case studies of military special operations missions to develop his theory. Case studies included successes and failures on the battlefield, across multiple wars, multiple nations, and multiple theaters. His theory is encapsulated in the graphic of an upside-down pyramid resting on the point of simplicity. The precariously balanced pyramid is impacted on one side by the destabilizing force of the friction of war and on the other by the stabilizing force of the moral factors imbued in special operations forces. McRaven asserts that every special operations mission has three phases: planning, preparation, and execution. Within those phases are six principles without which mission success is unlikely. The six principles are simplicity in planning, security and repetition in preparation, and surprise, speed, and purpose in execution. McRaven found that these principles dominated every successful mission. He states: “If one of these principles was overlooked, there was invariably a failure of some magnitude.” (p. 8) This series of articles will adapt McRaven’s theory and apply it to fireground operations and fire department culture, leaving aside the principles of surprise and security, which have little relevance to firefighting.

This first article addresses the planning phase and the principle of simplicity. Additional articles will address:

- The preparation phase and the principle of repetition

- the execution phase and the principles of speed and purpose

- the countervailing forces of the friction of war, including chance and uncertainty along with the moral factors of courage, perseverance, and motivation.

I will include examples specific to the fireground and examples of the broader application of McRaven’s theory to fire department culture, making the case that the odds of meeting the mission of saving lives improve if nearly every decision is viewed through the lens of McRaven’s theory.

Applying McRaven’s Special Operations Theory to the Fireground: Planning and the Principle of Simplicity.

McRaven’s theory gives three phases of an operation, planning, preparation, and execution. These phases both reflect and are dependent upon each other. Planning is the first phase of fireground operations and is most commonly represented by the standard operation guideline (SOG). Here I will outline how the planning phase and the principle of simplicity can guide the development and ongoing adjustment for SOGs while providing examples from the fireground as well as the broader application of simplicity to fire department culture and decision making.

“Simplicity is the most crucial, and yet sometimes the most difficult, principle with which to comply…”

Admiral William McRaven-

Simplicity

The pyramid portraying the theory of fire operations is balanced, and built, on the principle of simplicity. This is not to say the fireground is simple. It is not. Nor is it to say that firefighters and simple. They are not. Understanding the impact that simplicity has on the execution phase and the mission demands that we adopt a mindset of simplicity in the planning phase and apply that mindset at every opportunity. Decisions must be made about what an SOG says, how a fire apparatus or a fire station is constructed, physical and mental fitness programs, and which hose or ladder a department purchases. When deciding between equally effective options choose the simple one, the one that is easier to use, to deploy, to maintain. If selecting for effectiveness over simplicity, ensure that you understand and can account for the increased chance of failure the additional complexity introduces to the system.

Simplicity and the SOG

The planning phase should produce a set of SOGs that provides guidance for both the preparation phase and the execution phase. The SOG should make clear to the fire operations and training divisions what the commander’s intent is, the goals of the mission, and guidance on how the mission should be achieved. SOGs should be balanced between being descriptive enough to allow for consistent preparation and execution while not being so restrictive in language, or rigidly followed, that opportunities to achieve the mission are missed so as to remain in compliance with the written word of the SOG.

For departments that already have a set of SOGs, simplicity demands an open-minded review of what they say, how they say it, and where mission success might be falling short. An example of this comes from a major municipal department and their SOG related to the first-arriving engine and ladder companies for single-family residential fires. The SOG clearly stated the commander’s intent: to save lives. The language of the SOG then divided responsibility giving the first-arriving engine the responsibility to apply water to the seat of the fire, certainly a critically important task, and the first truck the responsibility for primary search of the structure.

In the preparation phase, training provided multiple opportunities to put this division of labor into practice. Engine companies stretched hose to the fire and then searched the fire room. Ladder companies would search the rest of the building. Because of this division of labor in training, well-meaning as it was, engine companies came to understand that their mission was fire attack and search of the fire room. They would put the fire out, search the fire room, and then begin overhaul. In the meantime, the search of the house, outside the fire room, was often not complete. The engine had accepted the mindset that searching was the truck’s responsibility. The mission of searching for fire victims to save their lives was delayed unnecessarily.

Once this shortcoming was identified through postincident analysis, the language of the SOG, the training, and then the execution on the fireground changed. This requires simply making it clear that completing the search is the commander’s intent, the highest priority on the fireground, and a responsibility of all members drove change in the preparation and execution phases. Engines still completed an aggressive fire attack to remove the primary fireground risk to potential victims and to firefighters. The engine still searched the fire room first, but now, both in training and execution, the engine would branch out and search adjacent areas working alongside the truck to complete the primary search as quickly and safely as possible. The result of this simple change in planning, preparation, and execution was a significant decrease in search times for single-family residential fires. Search is everyone’s job.

Simplicity Applied to Specification and Layout of Fire Apparatus

Now that we’ve covered an example of the principle of simplicity applied on the fireground, we will address simplicity as applied to the culture across an organization. Here we will use specification and layout (S/L) as an example of simplicity applied to apparatus for both the engine company and ladder company.

Simplicity of the Engine Company

When determining what, and how many, options are available, it’s best to follow the old adage, “keep it simple, stupid.” This is not because firefighters are not smart people. It is because McRaven’s principle of simplicity applies to fireground operations just like it does to special operations warfare. A simple plan is easier to practice. A simple plan is easier to implement. A simple plan is less likely to create unforeseen friction. A simple plan will be faster.

For example, to handle most fires, a fire department likely only needs one size of supply hose. Many departments have multiple sizes of supply hose and often revert to the largest supply hose available as a default. To simplify supply hose operations, a department must recognize that the size of the hose will impact any operation in many ways. Larger hose will supply more water, but it will also be heavier, harder to deploy, and take up more space on the apparatus. Simplicity then requires departments to identify how much water will be adequate most of the time. Knowing the required flow, with some margin for safety, the department can then purchase and deploy one size of supply hose. The smallest, lightest, and most reliable hose that will meet the necessary water flow requirements.

It defeats the principle of simplicity if a department purchases the largest hose available for the largest fire possible. This approach, while addressing the rare or outlier problem, unnecessarily complicates and delays day-in-day-out fire operations. Larger supply hose increases the time necessary to provide a supply in the initial stages of a fire and increases the workload and stress on the firefighters and engine operators. Larger hose also slows the post-fire process of picking up, reloading, and getting the apparatus back in-service. This increases the risk to the community as well as the potential for firefighter injuries.

Simplicity and the Ladder Company

When doing S/L for a ladder company, the priority is the mission and how the number and length of ground ladders will help meet the mission. Rescue is a primary function of ladder company operations. Rescue, though rare, is often performed from windows and is highly time dependent. Ventilation is also a primary function of ladder company operations, though it falls below rescue as a priority, and is less time sensitive than rescue. McRaven’s theory demands that we value simplicity and speed in rescue over other fireground functions such as ventilation.

The two-section, 24-foot ladder is lightweight, relatively short, and easily carried and raised by a single firefighter even on difficult terrain. The 24-foot ladder is long enough to reach the bottom of all second-floor and most third-floor residential windows. In my years in the Seattle (WA) Fire Department, we consistently had a two-section 24-foot ladder in the standard minimum ladder inventory. At some point, the department opted to exchange the 24-foot two section ladder for the 28-foot two section ladder. The 28-foot is longer and fits in the compartment, after all, and therefore it must be better, right?

But we should look at the choice using the principle of simplicity. The 24-foot ladder is two feet shorter than the 28 when closed, making it easier to carry and maneuver on the fireground (Duo-safety Products, 2023). At just 90 pounds, the 24 is also 22 pounds lighter than the 28-foot ladder. Lower weight translates into an easier, faster, and more reliable one-person deployment on the fireground. While these may seem like small differences between the ladders, only two feet longer and 22 pounds heavier, the principle of simplicity demands you assess what fireground advantage you are buying with the complexity of additional weight and length. While the additional four feet of ladder marginally increases the opportunity for roof access, it does not significantly increase the number of residential windows accessible for rescue or search. Given the same level of training and physical fitness of an individual firefighter, the 28-foot is more difficult, and slower, to carry and raise, therefore carrying an increased risk for mission failure.

When a victim is at a window, a ladder is our primary tool to achieve the mission. The principle of simplicity demands that the 24-foot ladder is the right choice when the mission is to save lives. When creating the ladder specification for a new ladder purchase, a minimum of 115 feet of ground ladder is required. Putting rescue and the 24-foot ladder at the top of the ladder specification the department would also need to ensure that ventilation needs were accounted for by providing other lengths of ladders, like a 35-foot ladder or a 45-foot ladder, and each of these should be the minimum length and weight possible to safely achieve the identified objectives.

It is also possible that a department might have unique terrain or building features that demand the purchase of 28-foot ladders instead of 24. So be it. The discussion here is to make the choice based on the principles of simple, fast, and effective by identifying and prioritizing fireground priorities and purchasing equipment accordingly.

*

This article introduced Admiral William McRaven’s Theory of Special Operations and begins to describe how the theory can be applied to fireground operations, and indeed, all fire department thinking. This article focused on the planning phase of fire operations and the principle of simplicity applied to the fireground. Then we discussed simplicity as applied to examples of S/L for engine and truck apparatus. The principle of simplicity should be considered during each phase of a fireground operation beginning with the development, or review, of a department’s SOGs, followed by training, followed by execution on the fireground. Fire departments should pursue a simple plan, repeatedly and realistically rehearsed, and executed with speed and purpose. Simple, fast, effective.

PHIL JOSE retired as a deputy chief from the Seattle (WA) Fire Department after 30 years of service. He chaired the Standard Operating Guidelines and Post-Incident Analysis committees. Jose has been an FDIC International instructor since 2004. He was named Chief of the Year in 2014 and was a co-recipient of the FDIC International 2008 Tom Brennan Training Achievement Award. He is the co-author of Fire Engineering’s Air Management for the Fire Service (2008), its Train the Trainer (2015) video; the “Bread and Butter” SCBA video (2012); and the new book, Instructor 1 for Fire and Emergency Services (Fire Engineering).