Part 3

By Phil Jose

This is the third and final article applying Adm. William McRaven’s Theory of Special Operations to fireground operations and fire department culture. McRaven’s theory, adapted to fire operations and culture, includes three phases encompassing six principles, four of which apply to fire department operations, for mission success. An explanation of McRaven’s theory, focusing on the planning phase and the principle of simplicity, were contained in the first article. The second article addressed the preparation phase, which includes the principle of repetition. This article addresses the execution phase, which includes the principles of speed and purpose, and the competing dynamics of friction and the moral factors.

Applying McRaven’s Special Operations Theory to the Fireground: The Execution Phase

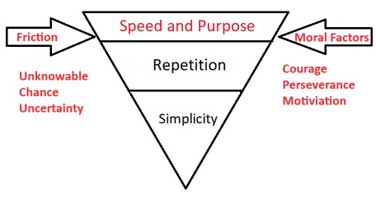

McRaven’s theory of special operations divides the execution phase into three parts: surprise, speed, and purpose. As mentioned before, the principle of surprise is not very applicable to the fireground and won’t be discussed here. The twin principles of speed and purpose are both critical on the fireground, and therefore mission success. To save lives, we must start with a simple plan. The plan must be honed and practiced through repetition at the individual, company, and multi-company level. That plan must then be executed with both speed and purpose when the fire department responds to an emergency. In addition, the execution phase brings to bear the opposing forces of friction and the moral factors. This article will explore the execution phase and how these factors fit together in support of the overall framework of McRaven’s theory applied on the fireground and in fire department culture.

Speed and Task Completion

We will consider speed from the two angles of physical speed on target and the mental speed required to adapt the plan to the situation at hand.

In a special operations mission, the concept of speed is simple. Get to your objective as fast as possible. Any delay will expand your area of vulnerability and decrease your opportunity to achieve relative superiority.

McRaven, 1996, p19.

First is the speed at which each individual and team moves in the completion of their objectives. Speed in the physical execution of skills is largely a function of the preparation phase. Training provides repetition, and repetition results in speed on target. McRaven developed his theory by examining military special operations and special operators who, by and large, are already subject matter experts in the skills of their trade. We are applying the same principle to both the rookie and the veteran. For rookies learning a new skill like hose deployment or forcible entry, the physical skill alone requires all their mental focus, and they perform rather slowly. In hose deployment, for example, new trainees move at a slow walking pace, deploy sections of hose, come to a stop when it is time for the final deployment of the nozzle and working sections of hose, then deploy those thoughtfully. Trainers will focus on completion of the task correctly then increase speed. A good training program will have a trainee increase speed only to the point where errors begin to occur. At this point, the speed should stay consistent until there are no mistakes, then the speed is increased again. In the fire service, this is often referred to as the “crawl, walk, run” method. By the end of the training cycle, the new firefighter should be able to perform the physical skill of deploying hose quickly and accurately. In addition, they begin to do so with muscle memory, which frees their mind to consider other fireground information as part of their overall tactical assignment.

Veteran firefighters still need significant sets and reps of the same skills to maintain their base level of competence and to increase that competence to a mastery level so they can perform the skill quickly, accurately, and essentially by rote. This mental competence breeds both mental and physical speed on target and the ability to adjust the plan as required by the situation on the ground when the building is on fire. Experts adjust the hose stretch to quickly and accurately maintain speed on target. Experts identify obstacles such as trees, cars, and fences, stretching through them to the obstacle, providing a kink free and easily advanceable attack line. In the same situation, a novice will often make a mistake in the stretch that causes the hose to be caught on friction points that the expert avoids. Though both may complete the stretch in the same time, the value of expertise is apparent in the relative success achieved once the line is in use. The expert is operating at a faster mental speed and therefore with greater competence in achieving the mission.

Speed and Adaptation

McRaven maintains that speed is primarily a function of repetition in training. Speed is more than just the individual or team ability to perform tasks or tactics quickly. Speed also encompasses the ability of the individual and the team to adapt the plan, as trained, to the situation as it exists at the time of the fire. McRaven states that “. . . the concept of speed is simple. Get to your objective as fast as possible. Any delay will expand your area of vulnerability and decrease your opportunity to achieve relative superiority.” (McRaven, P. 19)

One example of this principle on the modern fireground is the discussion of whether the first-arriving engine company at a residential structure fire should proceed directly to the fire building or should stop at the nearest hydrant to conduct supply operations before proceeding to the fire. If we adopt only the principle of speed as described by McRaven, it would become immediately apparent that the time delay to stop at a hydrant for supply, and possibly even leave one of the firefighters behind, does not meet the requirement to “Get to your objective as quickly as possible.” (ibid)

We can consider the two options, respond directly to the fire, or stop and lay forward, in a broader sense, and apply McRaven’s other principles to the two operations. Which better achieves the principle of simplicity? I would maintain that driving directly to the fire location does. Stopping at the hydrant requires several steps: stop at the hydrant, dismount the apparatus, gather the tools and hose then leave them at the hydrant, remount the apparatus, then deploy supply hose from the rear of the apparatus. There is potential failure at almost every step in that process and while each step is not individually complex, overall complexity increases substantially. More complexity equals more opportunity for failure. The second-arriving engine can complete these same tasks, and, though they would still have the same complexity, a failure in the process would be much less likely to have a negative impact on achieving the mission: to save lives. (A more thorough discussion of supply operations for the first arriving engine can be found in the April, 2021 edition of Fire Engineering Magazine)

Purpose

“Purpose is understanding and then executing the prime objective of the mission regardless of emerging obstacles or opportunities.”

(McRaven, 1996, Pg. 21)

Purpose is the embodiment of the mission of the organization in the action and commitment of each individual member of the team. Common to fire department is the phrase “Our Mission is to Save Lives.” Every action, every decision, is beholden to the mission of the organization. Every member of the organization must know and live the mission. This might seem simple in the view of some, but firefighters know the difficulty inherent in achieving the mission in the high risk, complex, and unforgiving environment of the fireground. The standard operating guidelines (SOGs) must reflect the mission statement and then translate it into actionable strategies, tactics, and tasks. Those must be simple, practiced with repetition, and then implemented with speed and purpose.

Another aspect of purpose is the individual firefighter’s personal commitment to achieving the mission. McRaven maintains that “In an age of high technology and Jedi Knights we often overlook the need for personal involvement, but we do so at our own risk.” (Mcraven, 1996, p 23) Clausewitz further states, “Theorists are apt to look on fighting in the abstract as a trial of strength without emotion entering into it. This is one of a thousand errors which they quite consciously commit because they have no idea of the implications.” (as quoted by McRaven, 1996, p23.)

Friction and the Moral Factors

Friction occurs when any combination of factors work to limit progress toward achieving the mission. Examples include things that are unknowable, such as the presence or absence of victims in the structure. The element of chance can be represented by things such as closed railroad crossings or out of service hydrants close to the fire, and the element of uncertainty is a constant companion for anyone who must make life-and-death decisions in short time frames with limited information. Friction is an ever-present force on the fireground from the moment of the initial call into the 911 center until the last apparatus leaves the incident scene. Friction is trying to kill the plan and limit the ability to achieve the mission. Represented in the pyramid from McRaven’s initial work friction is trying to push the plan over and cause it to come tumbling down on your people and the citizens we serve.

Opposing friction is the stabilizing force presented by the moral factors first described by Clausewitz (1827) and then identified by McRaven as courage, perseverance, and motivation. In every fireground operation, there will be friction. The individual firefighter, company officer, and chief officer must recognize that their personal commitment to the mission is what overcomes friction and wins the day. Their courage. Their perseverance. Their motivation. No doubt that each reader of this article can remember a time and place where they, or their team, carried on in the face of fireground friction. It might be a major decision or action on the fireground, but it can also be as simple as looking down to see a kink in the line and choosing to take action to remedy the problem. A good example of this commitment to meeting the mission is the phrase “never walk by a problem you can solve.” It does not matter if it is “your job.” If you can, fix it.

“Over time the frictions of war work only against the special operations and not against the enemy.”

McRaven, p19

While friction is common on the fireground, it would be remiss not to recognize that the fire department culture can also have friction that negatively impacts the mission. Personnel problems, political feuding, toxic leadership, or a lack of focus on the mental health of the employee can and do lead to mission failure. It is not enough to be committed to excellence on the emergency scene. To be truly effective, we must recognize the impact of friction, whatever its source, across the organization and find a way to bring the moral factors to bear against it. Possibly the largest source of friction on the fireground comes from an attitude of complacency in the fire station or the training ground. The ability to recognize and overcome friction is only possible when there is an attitude of commitment to both planning and repetition.

*

This series of articles sought to take William McRaven’s special operations model and adapt it to fireground operations and fireground culture. The result is an understanding that every decision and every action taken by a fire department, and its membership, can be looked at through the lens of McRaven’s theory. Our operations must be simple, fast, and effective. Whether choosing where to build new fire stations, what hose to purchase, or developing an SOG, the options must be evaluated by their ability to meet the mission. Each of these should start with a simple plan. The plan should be regularly and realistically practiced. The plan should be implemented with speed and purpose.

PHIL JOSE retired as a deputy chief from the Seattle (WA) Fire Department after 30 years of service. He chaired the Standard Operating Guidelines and Post-Incident Analysis committees. Jose has been an FDIC International instructor since 2004. He was named Chief of the Year in 2014 and was a co-recipient of the FDIC International 2008 Tom Brennan Training Achievement Award. He is the co-author of Fire Engineering’s Air Management for the Fire Service (2008), its Train the Trainer (2015) video; the “Bread and Butter” SCBA video (2012); and the new book, Instructor 1 for Fire and Emergency Services (Fire Engineering).