By Robert Delagi

Historically, “survey the scene” was a yes/no activity done while approaching the incident scene. Once the “scene was safe,” emergency medical services (EMS) providers were conditioned to move on to initial and ongoing patient assessment and care and to look for signs of patient decompensation. Little attention was paid to “scene decompensation” and “ongoing scene assessment.” Often, EMS providers are surprised by an unanticipated act of violence against them and hastily retreat in panic mode with injury to the providers.

We are accustomed to staging in a safe area while waiting for additional resources to render the scene or the patient safe prior to assuming EMS operations. We are very good at staging and waiting when there is a known hazard such as violence, assault, domestic, psych/behavioral, chemical, and the like. Once the scene is cleared, we rush in to lay hands on the patient because we are conditioned to measure our treatment times and scene times as markers of success. We are distracted by the intense focus on the need to multitask patient-care activities, paying significant attention to the details of the physical assessment and the use of technology we have grown accustomed to for accurately assessing and treating patients. We generally work on teams with small numbers. The unintended consequence is that we frequently forget to remain vigilant for developing hazards.

EMS Work Is Dangerous

The numbers clearly show that EMS is a dangerous profession. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH), 10 percent of all injuries suffered by EMS providers are attributed to acts of violence, and violence against EMS providers is a whopping 22 percent higher than violence against the national average workforce. In this article, we will explore applying the commonly used approach to monitoring for adequacy of breathing to monitoring an EMS scene.

Two case studies of recently occurring events in the United States exemplify the need for a renewed focus on first responder safety while operating at an EMS scene.

Mark B. Davis, 25, was killed in the line of duty in Cape Vincent, New York, while caring for a patient with ischemic chest pain. In the second incident, John Ulmschneider, 37, was killed in the line of duty in Prince George’s County, Maryland, while forcing entry into the home investigating a report of an unconscious diabetic. Both were common everyday call types where there was no previous indication of an unsafe scene, yet each resulted in a line-of-duty death of a dedicated first responder and family man.

The “National EMS Culture of Safety Document” (2013) cited: “A positive safety culture is expected to result in decreased risk, fewer errors, fewer adverse events, and [fewer] other negative safety outcomes …. The goal is an EMS culture in which safety considerations permeate the full spectrum of activities of EMS leaders and practitioners everywhere, every day – by design, attitude, and habit.”

We are operating in an environment where there is increased threat from patients who may not want help or understand the need for help and family/friends/bystanders who may not want help, understand the need for help, who may be trying to hide something, or who may be highly motivated to prevent you from helping.

We must learn from case studies such as these and many near-miss events reported in the literature, change our behavior, and modify our approach to scene assessment. We need to move away from the disillusioned concepts of safety and our oath to put the lives of others ahead of ours. Borrowing a doctrine from high-functioning teams, such as the United States Navy SEALs, we need to embrace a philosophy where each emergency response is a mission – we deploy together, operate together, and return home together – and where scene safety is no longer a yes/no question but a “constantly evolving” situation.

General Impression of the Scene

Let’s take a closer look at the “general impression” of the scene. On arrival, consider parking the ambulance based on egress needs instead of optimal access to the patient. When approaching the occupancy, be mindful of maintaining a clear egress path, and look at areas of cover or concealment. Note the position of hinges on doors so you know which way doors swing open. Note the affect of the patient and bystanders. Make a mental tally of people in the room, and ask if any others are on location. More on that later in this article.

In the fire service, the use of an incident safety officer (ISO) is a proven concept in which a dedicated member of the command staff is tasked with looking at big-picture items such as structural integrity, smoke volume and density, fire load, improving or deteriorating conditions, and progress of the firefighting teams while the incident commander concentrates on tactics and operational crews focus on their respective task at hand.

This is a time-proven successful strategy that simultaneously combines ongoing scene assessment with ongoing tactical objectives. This concept is easily adaptable to the EMS scene, even where crews typically operate with fewer personnel dedicated to the job – for example, a Contact EMT performs primary patient survey and directs all treatment, including performing most of the skills necessary while the Cover EMT performs secondary scene survey, monitors crowd size and affect, remains aware of evolving hazards, and performs ongoing scene assessments.

While one provider is more focused on patient care, the other provider is more focused on the scene. Of course, this is a concept that can be easily modified based on available resources. The number of providers is not as important as ensuring that appropriate attention to detail is evenly distributed so that fixation on patient-care needs does not come at the sacrifice of a thorough and ongoing scene assessment.

Crews should have a prearranged distress word as a signal for hasty retreat. Similarly, EMS educators should build deteriorating condition scenarios into patient assessment training throughout original certification and continuing education efforts to prepare students and reinforce these concepts.

Valid reasons for withdrawal include fear for personal safety and having to act in self-defense. This is not abandonment; this is applying the scene safety doctrine historically used on initial approach to a scene that changes from docile to hostile. If a hasty retreat is necessary, it is important that EMS crews do not leave the scene but retreat to a safe location proximate to the hostile area and ensure that law enforcement is on scene to mitigate the threat. Once the threat has been mitigated and the scene is rendered safe again, patient care may resume. Thorough detailed justification documentation on the run report is essential.

Adapting Patient-Triage Methods

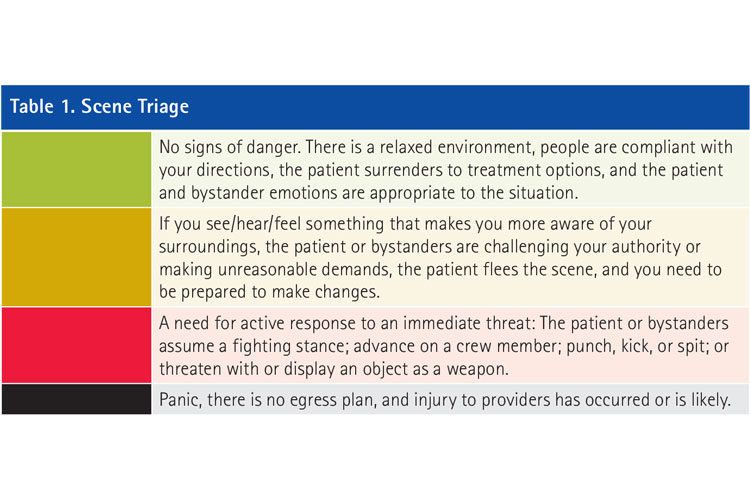

Another helpful strategy may be to adapt the triage-oriented decision-making process and familiar color-coding assignments applied to patients for application to the scene. Just as we have been conditioned to up-triage or down-triage patients based on physiology and patient response to interventions, we can up-triage or down-triage the scene based on evolving scene dynamics, much like the ISO makes judgments based on improving or deteriorating conditions:

- Mentally tag the scene green if there are no signs of danger, there is a relaxed environment, people are compliant with your directions, the patient surrenders to treatment options, and the patient and bystander emotions are appropriate to the situation.

- Mentally tag the scene yellow if you see/hear/feel something that makes you more aware of your surroundings, the patient or bystanders are challenging your authority or making unreasonable demands, the patient flees the scene, and you need to be prepared to make changes.

- Mentally tag the scene red if there is a need for active response to an immediate threat; if the patient or bystanders assume a fighting stance or advance on a crew member; if the patient or bystanders punch, kick, or spit; or if there is a threat or display of an object as a weapon.

- Mentally tag the scene black if there is panic, there is no egress plan, and injury to providers has occurred or is likely.

Always remember that this is a dynamic process and that just as patients decompensate physically, the scene can decompensate from docile to hostile with little warning.

Remember to maintain situational awareness of your surroundings and your location on the scene; be aware of your partner’s presence at all times; observe and plan the best egress routes to safety to extricate yourself and others from the scene; ensure communication with dispatch with current status so that dispatch will be able to send help if needed; and be guarded against patients, family members, staff, bystanders, and so on, as they can turn on you or be deceitful at any time. During physical assessment, be alert for the presence and potential for concealed weapons or sharp objects; and always control your patient’s access to his belongings and others’ access to their belongings after you have initiated care.

ROBERT DELAGI, MA, NRP, has 40 years of experience in fire, rescue, and emergency medical services (EMS) and has developed domestic preparedness, hazardous materials, and safety curricula for the fire service and general industry. He has conducted several research projects, is a published author, and has presented at national and international conferences. He is an adjunct assistant professor at Suffolk County Community College and an adjunct instructor at SUNY Empire State College. He is certified by the National Board of Fire Service Professionals as an incident safety officer and a health and safety officer; is the medical branch director of the Suffolk County Urban Search and Rescue Task Force; and sits on the Suffolk County Terrorism Response Task Force and the New York Downstate Urban Area Work Group for Domestic Preparedness, linking EMS and public health disciplines to emergency response efforts.

The SAMPLE Survey

Putting the Scene Survey into Motion: Pedestrian Safety and the Fire/Rescue Apparatus

Scene Safety: Violence Against Firefighters

Fire Engineering Archives