On October 26, 2018, just after lunch at 12:55 p.m., Raleigh (NC) Fire Department (RFD) Engine 13 and Ladder 4 responded to a fire alarm activation at Glenwood Towers, a 14-story residential high-rise in the city’s Glenwood South district, at the corner of Glenwood Avenue and West Johnson Street (Figure 1). Built in 1971, the nonsprinklered, standpipe-equipped Type I fire-resistive building has more than 300 apartments. The apartments and public corridors were equipped with smoke detectors. The building’s center section extends to 14 stories; two attached wings extend to 10 stories.

Engine 13 approached from the Tucker Street side (Division B) with nothing visible from Tucker or Glenwood (Division A). On exiting the engine and entering the building, the crew noticed that the elevators had been recalled to the lobby and were open and that some occupants said there was smoke on the floors. Ladder 4 approached from the West Johnson Street (Division D) side and noticed fire coming from a window on the ninth floor. The information was relayed to the communications center, and the alarm was upgraded to a working fire.

RELATED

Improper Staging Can Set a High-Rise Operation Up for Failure

Sheridan: High-Rise Firefighting Lessons Learned

High-Rise Firefighting Lessons Learned

Within one minute of the upgrade and prior to firefighters ascending, command requested a second alarm because numerous occupants needed assistance evacuating. As the initial fire alarm response personnel were ascending the West Johnson Street stairwell, they met numerous occupants fleeing down the stairs. Several of the occupants with black soot around their noses were crying and holding onto the railing as they descended.

Figure 1. Glenwood Towers Aerial View

Imagery ©2019 Google, TerraMetrics.

Personnel started to smell smoke on the third floor and met a moderate amount of smoke on the eighth floor. They donned self-contained breathing apparatus (SCBA) prior to entering the ninth floor. As the initial crews entered the ninth floor, they encountered thick black smoke from the floor to the ceiling throughout the floor. While the crews attempted to find the seat of the fire, they met numerous victims who needed rescue for evacuation.

The zero visibility and effort to rescue victims hampered the firefighters in finding the seat of the fire. The original search group attempted to use a thermal imaging camera (TIC), but it provided no assistance because of the conditions. The search group also began using a search rope for orientation; but because of the number of people needing rescue, the rope was abandoned so personnel could escort them out. Firefighters reverted to wall-oriented searches using tools to locate doors and to find any victims lying on the floors in the apartments.

The emergency communications center was receiving calls from occupants trapped on several floors or from their families; command assigned incoming personnel to assist with their removal. The search teams assigned to the floor above and two floors above the fire had to force doors to find additional tenants inside apartments. Some of the searches were expedited by obtaining the floor and apartment layout from the floor below prior to entering.

The standpipe connections were on each floor inside the hallways instead of the stairwells. Since the fire apartment was unknown, the initial crews attempted to connect on the fire floor because the length of the stretch needed was unknown. The standpipe connection was approximately seven feet inside each hallway from the stairwell entrance. Because of the smoke and the difficulty in opening the standpipe, the attack hose was relocated to the floor below. While charging the two-inch attack hose from the floor below, the hose became wedged under the stairwell door. Personnel quickly remedied the issue by cutting off the standpipe outlet to relieve pressure and continue the stretch.

Because the smoke made finding the involved apartment difficult, Engine 1’s lieutenant, on the ground outside the building, guided interior crews to the fire apartment while he was supplying the fire department connection. The lieutenant had instructed the attack team on entering the building to use the West Johnson Street stairwell to get to the fire floor (the ninth); the involved apartment was the first one to the left of the stairwell. The fire was extinguished quickly thereafter.

Postincident Analysis

As with any incident, firefighters always need to examine what went well, what did not, and what needs attention. Within 48 hours, many first-alarm companies and personnel participated in a postincident analysis. This fire reminded us that complacency takes various forms. Many consider firefighter complacency signs as a low level of job knowledge; a lack of desire to maintain a current skillset and improve; and confidently stating, “We will always make it work.” Imagine if a football team never ran routes and plays or if a major league pitcher never threw in the bullpen. If thrown into a game without preparing, working on the mechanics, and developing muscle memory, these athletes would fail. The fire service will suffer the same performance decline if we allow ourselves to slip.

One key lesson learned is that the large amount of information responders obtain in seconds or minutes must be compiled into an action plan and communicated effectively.

Lessons Learned and Reinforced

Command

Maintain focus. From the incident management perspective, we must thoroughly understand our procedures, our response area characteristics, and our responders’ skill sets. However, all of the first-alarm chief officers that day were serving one level up from their normal position duties. Normally, I am assigned to Battalion 3, as the first-due battalion chief for the Glenwood South area.

As a captain, I was assigned to Engine 13, the first-due engine to Glenwood Towers. That progressive engine company had created preplans for most of its first-due buildings. In responding to Glenwood Towers, the crew already knew the building layout, the stairwell locations, the initial stretch lengths needed, the tenants who could provide responders with information, and whom to contact. Although I still recalled this information from serving on Engine 13 before, acting this time in a command role increased the difficulty of applying it.

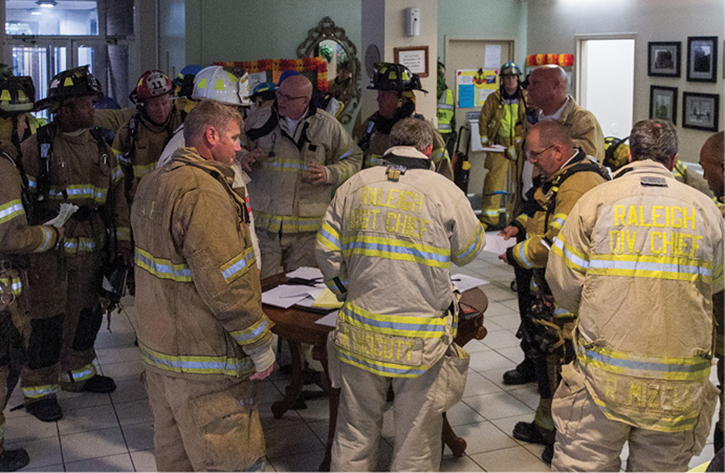

(1, 2) On the arrival of Ladder 4, fire was evident from a ninth-floor window on the West Johnson Street side. This incident reinforces the need to view all areas of the building on arrival to gain insight into expected conditions. After supplying the FDC on the Delta side, a lieutenant, knowing the interior floor layout, directed interior attack crews to the fire location from his position outside. (Photos by Mike Legeros.)

(3) The command post was in the lobby. The postincident review recommended, when possible, placing the command post in a remote area. In the lobby, all the incident management personnel were in the path of incoming personnel and evacuating residents.

Based on the fire apartment number I received, I should have been aware of which stairwell to use for attack and the general apartment location. On arrival, the interior crews told me that the fire was in apartment 927; the audio recording from the incident confirms that I heard and answered that transmission. However, I was so focused on all the additional information and the crews entering the building that the implications of that crucial information did not register. The crews used the correct stairwell, but smoke conditions kept them from finding the apartment quickly. The first learning point: I was unable to recognize all information in the initial incident stage and to more quickly direct the attack group to the fire.

Additionally, before our assistant chief of operations relieved me, I established command in the lobby. Although our policy requires that each unit dispatched be assigned, I was quickly overwhelmed. Crews were entering the lobby and proceeding upstairs following preestablished roles outlined in the policy. At the time, I did not recall who they were and what role they were performing.

My prior experience with the engine company involved an offensive operational mindset. In the lobby, years later, I needed to operate from a command perspective. I was not thinking about the prior building experience. At this incident, once assigned to the operations above, I was managing tactical resources, which was more closely related to my previous experience on the engine.

Accountability. We need numerous personnel to create the command structure to support the activities required at a high-rise incident. To assist with limiting the impact, designate an interior staging location for additional crews. Using an accountability board to track resources proved ineffective because of the number of personnel and the activity within the stairwell.

When there are many responders who are not familiar with the building, mark the division designation on the stairwell with a permanent marker to improve communication and awareness.

Command post (CP) location. It is critical to keep unnecessary personnel away from the CP. As the incident grows, the CP will expand. We should also consider placing the CP in a strategically isolated area. We could have placed the CP in a small TV room adjacent to the lobby, which would have moved the command personnel away from the lobby traffic.

(4) The standpipe connections in the hallways. Although incidents vary, hooking up to the floor below is the best practice.

During this incident, many of the evacuated occupants filled the additional lobby space. A little later, a shuttle bus for evacuees was staged on an adjacent street. We could have also moved the evacuees to a nearby building as an option.

Apparatus. I needed to step back and pay attention to what apparatus were responding to ensure that the needed resources were arriving. I quickly became too focused on the fire problem and not on managing the resources and the action plan.

Adaptation. A positive was that our crews proved to be adaptable. In Raleigh, a standard fire alarm dispatch includes one engine and one ladder, as at this incident. The on-scene size-up report and updates were calm and confident while upgrading the response and requesting a second alarm. But, this incident was upgraded only to a working fire response, not to a high-rise response.

A structural fire response receives four engines, two ladders, one rescue, and two battalion chiefs. A high-rise fire response receives five engines, three ladders, one rescue, two battalion chiefs, one division chief, a fire marshal, and an air unit. The upgraded dispatch lacked one additional engine and ladder. This necessitated that all apparatus responding adjust, and some assignments were not fulfilled on the initial arrival. The last-arriving engine on the first alarm had to either establish a rapid intervention group or assume lobby control. I was asked which role I wanted the engine to assume. The engine crew recognized the lack of the fifth engine usually sent on a high-rise response. The last engine on the initial alarm response was used to assist in the stairwell. Second-alarm companies filled the lobby control and rapid intervention roles.

Our personnel adapted extremely well to this deficit and prioritized where the help was needed. Our personnel’s aggressive actions resulted in effective searches and victim removal. The search activities followed basic techniques; using the search rope and the camera were ineffective.

Communication. Using face-to-face communication was helpful for many of the crews from the floor below to the top floor. By designating a suppression branch (the fire floor) and an upper branch (all floors above the fire floor), the directors could verbally give orders and maintain effective communication with their assigned personnel for updates.

Operations

Alarm upgrade. The original incident was a fire alarm activation in the computer-aided dispatch (CAD) system. The upgrade from the initial fire alarm response to a working fire response did not provide the appropriate resources to complete the response card. The call class was not changed to a high-rise response when the incident was upgraded, so the CAD did not recommend the correct number of units. As a result, a rapid intervention team was not established on the first alarm.

Fire location. The first-due crew should confirm the fire location prior to committing to a standpipe location. Because of the long hallways and no visibility in the high-rise, maintaining crew integrity was difficult. The crews found a large amount of smoke in apartments adjacent to the fire apartment on the fire floor and on the floors above.

Search technique. Two floors above the fire floor had to be searched and evacuated at the same time. To develop proficiency in this operation, we need to create search drills that match the conditions at this incident. Some of our crews have practiced search drills with hallway and smaller room settings with no hose and rope since this incident. They also looked into why the use of the search rope was ineffective at this incident. They discovered that it had been improperly deployed. The rope was not deployed in a manner to maintain tension and be elevated off the floor. Additional crews on arrival stepped on it and moved it as they entered.

Standpipe. The difficulty in opening the standpipe valve taught us that we must be familiar with all the options in the high-rise kit. Personnel had to use a pipe wrench to open the valve to supply the attack line. Since the resources were shifted to assist with rescues, the later-arriving company that made the attack was not fatigued from rescue and evacuation activities. Once the attack line was in place, the apartment door would not stay open because the debris in the apartment was pushing it shut; personnel had to maintain the opening. An additional lesson with the high-rise hose complement is that once it is deployed in a stairwell, be ready to work out the kinks if the apartment is close to a stairwell.

(5) The smudged areas in the middle of the walls are indications of the oriented search by personnel under no-visibility conditions.

TIC use. As the search teams were opening doors and finding victims, some residents were forced to evacuate. It was difficult to see the apartment numbers and communicate their locations because of the smoke conditions. The search team could not view the TIC display because of the smoke density, even after they wiped and cleared the camera display. At the incident review, wiping the germanium lens in the front of the TIC was recommended.

Search completion designation. This incident also demonstrated the need to adopt a standard method to confirm search completion in apartments. The number of personnel and activity on the ninth floor and above showed that we should have established an entry officer on the eighth floor. This position should have been announced to responders headed to the upper floors, instructing them to check in on the eighth floor and receive an assignment. The operations and divisional supervisors eventually placed all unused personnel back to the eighth floor, the resource floor, for assignment. This action improved tracking and task allocation. The essential need for companies to bring spare SCBA cylinders to the resource floor is critical.

Looking to the Future

As a result of our postincident analysis, our department has adopted the following improvements.

Awareness. To enhance awareness, one recommendation was that all personnel take a quick view of the building exterior before entering to gain any valuable data regarding the fire location and possible egress and ingress routes.

Annunciator panel. We also determined that the first-due companies and the first-due chief should check the annunciator panel for an idea of what is going on. The first-due chief may see additional alarms have activated after the first-due arrival.

Initial attack line connection. The crew initially decided to connect the attack line on the fire floor because the fire’s location was unknown. They doubted whether they had enough hose to stretch from the floor below. After a postincident review, we decided that we should always connect to the floor below. In many buildings, this will necessitate that attack crews bring up additional hose to cover the additional stretch distance from the stairwell. In the future, if the fire location is unknown, we can consider having separate companies establish separate attack lines from different stairwells.

Accountability. Even though department policy mandates establishing a secondary accountability location at the hose connection, we did not establish a collection point. The postincident analysis identified the advantage of announcing the connection location once it is established.

Focus on the assigned task. This incident reinforced the importance of each company’s focusing on its assigned task. The initial crew assigned to establish a hoseline encountered a seized standpipe valve and had to choose between assisting with rescues and accomplishing the hoseline task. The postincident discussion noted that although rescues are important, we must be diligent and complete the task assigned.

Rescues. Although it is well-known that you can use the layout of the floor below as a guide to the layout of other floors in a structure, not everyone practices this elementary skill. An additional company assigned to search scanned the layout of the floor below before entering the assigned floor and thus proceeded directly to an apartment for a rescue. Many of our resources became engaged in rescue efforts while ascending the stairs around the sixth floor. The postincident review revealed that because of no-visibility smoke conditions, residents on the lower floors who were unaffected by smoke and not endangered by the fire location should have been sheltered in place.

Evacuations. We should also consider establishing a casualty collection point in a safe area for evacuated residents. Another operational consideration is to deploy resources in a stairwell to assist with evacuations; this would limit the crews needed from the floors above to escort victims to the ground level. Once the second alarm companies arrived, the CP assigned many to this task. First-due personnel established the attack stairwell; evacuation stairwells were not established originally. As the command post personnel increased, an evacuation stairwell and group were established to support the search crew efforts.

This incident was a great test of our personnel, policies, training, and functionality. The responders that day proved their dedication and desire to perform and saved many occupants’ lives. The responders’ openness in the postincident review demonstrated their desire to improve. Our goal is to use the points highlighted in this summary to improve our delivery of service and preparation for future incidents.

Christopher Wilson is a battalion chief and instructor with the Raleigh (NC) Fire Department, which he joined in 1997. He entered the fire service as an Explorer (Junior Firefighter) in 1988 and served as chief of the Falls Volunteer Fire Department from 1997 until its merger with the Wake Forest Fire Department in 2012. Wilson has an associate degree in fire protection technology.

Podcast: Raleigh (NC) Battalion Chief Chris Wilson talks to Joe Pronesti