In his opening address to attendees of FDIC International 2023, Chief David Rhodes hit a home run with his remarks on mental health:

“There has really been little focus on the mental health effects of poor leadership. We tend to talk about PTSD because we can blame that on an incident beyond our control. But we don’t want to talk about the root cause of the MAJORITY of the stress that causes us issues: organizational vindictiveness, discrimination, favoritism, and exclusion.” – Chief David Rhodes

- Upstream Practices That Predict Firefighter Resilience

- Firefighter Stress Resilience and Increasing Emotional Bandwidth

- PTSD: Don’t Move Next to an Airport and Complain About Airplane Noise

- Addressing Internal Conflict to Understand Suicide

In the last decade, tremendous effort has been placed on addressing suicide, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), anxiety, depression, and other poor mental health outcomes impacting firefighters and first responders. It appears the primary outcome of our efforts is increased incidence and reporting of negative outcomes from “the calls.” For years, I have known that there are so many other factors that impact mental wellness, and if we continue to blame only the calls, we will continue to silence those suffering from all the other stressors in life.

When we are unable to address our true sources of pain, healing remains elusive.

Authentic and meaningful relationships have the power to buffer against almost any stressor. This is because safety and terror are incompatible, and the greatest source of safety is found where trust exists. For organizations, healthy relationships are built on trust modeled from the top down. The absence of true leadership is a key contributor to poor mental health outcomes.

Organizational Stress

Several experts speaking on first responder mental health have shared similar findings. In his FDIC International classroom session, Chief Dan DeGryse shared that for his members in Chicago, the top two causes of stress mimicked data shared from Captain (Ret.) Frank Leto of the Fire Department of New York—relationships and organizational stress. Fascinatingly, the military and law enforcement communities, too, share that organizational stress was a key contributor to poor mental health outcomes.

Organizational stressors include lack of support, interpersonal conflict, scarcity mentality, exclusion, micromanagement, burnout, bullying, affinity bias, and harassment. Microaggressions, though subtle, are also common and erode trust and safety.

Tragically, for many organizations, the people responsible for the health and wellness of their first responders are often the same ones contributing to their poor mental health outcomes.

Personally, I believe in our effort increase professionalism, we have forgotten about the importance of the shared human experience and the need for trust and connection. This realization hit me hard as I read Dare to Lead by Dr. Brene Brown. She shared Air Force Colonel DeDe Halfhill’s story of addressing an epidemic of exhaustion from her soldiers. Initially, she intended to provide them with leave, but as she connected with and actively listened to them, she learned that they were exhausted, but not from the tempo of the work. Instead, they were being impacted by the isolation and loneliness of their deployment. As she researched further to find a solution, she recognized that our current military leadership doctrine is so sterilized that words like lonely, compassion, and empathy are nonexistent. She found this to be in complete contrast to the 1948 Air Force leadership doctrine. She shared: “As I was reading the document, I was struck by how much emotion I was feeling from the words on the page. So I started to pay more attention. The pages were full of words and phrases like to belong, a sense of belonging, feeling, fear, compassion, confidence, kindness, friendliness, and mercy. I was amazed.” (p. 65). She found the word “love” and “what means as a leader to love your men” was mentioned 13 times. Today’s military doctrine has replaced all those words connected to emotion with language such as tactical, strategic, and operational leadership.

There is no doubt that firefighters and other first responders work in high-stress environments. Although leadership through accountability is critical, leadership through caring is biological necessity.

Human Connection

In his book Tribe, Sebastian Junger shared that there was no relationship between combat and suicide among combat vets, and further shared that those veterans on the front lines did better mentally than those not engaged in combat. The variable he found that had the greatest impact on protecting combat soldiers:

Connectedness to purpose, mission, and each other.

The close relationships shared by combat soldiers produces a coregulation that served to buffer against the trauma faced. This isn’t just true of combat soldiers; during the Blitz in London, children who remained with their families in London and were exposed to the relentless bombings fared far better than those who were sent away as a form of protection.

In these cases, meaningful social connection outweighed trauma.

Social Resilience

Junger went on to share that PTSD is a disorder of recovery, and social resilience is a far better predictor of trauma recovery than both individual resilience and the trauma itself. People can endure a lot if they have strong support structures. Humans are wired to respond to stress, but they are also hardwired for connection and purpose.

This means that close relationships and healthy organizations are far better predictors of recovery from PTSD than any other variable, including the extent of the trauma itself.

You can tell a lot about organizational leadership by the mental health of the members. Poor leadership within an organization is a predictor of lack of recovery from trauma. A 2017 study found that perceived support from supervisors is the strongest predictor of reduced PTSD severity and mental wellness ( Stanley, et al.)

To Lead is To Care

By simply demonstrating they care and by modeling the behaviors they want to see from their members, leaders have incredible influence. As we have evolved as people, some of our primitive survival instincts have unconsciously remained active. The greatest rival to our survival instinct is the need to feel safe with others. This is because safety with others is a prerequisite for survival. When we work together and support each other, serotonin and oxytocin reward us with the feelings of security, fulfillment, belonging, empathy, trust, and our stress decreases. However, in the absence of safety, support, and trust, cortisol is released, and with its release oxytocin and its benefits are inhibited. Further, cortisol’s constant release yields a cascade of other ill effects on both our mental and physical health.

According to Simon Sinek: “Stress and anxiety at work have less to do with the work we do and more to do with weak management and leadership. When we know that there are people at work who care about how we feel, our stress levels decrease. But when we feel like someone is looking out for themselves or that the leaders of the company care more about the numbers than they do us, our stress and anxiety go up.” (Sinek, p. 33.)

Psychological Safety

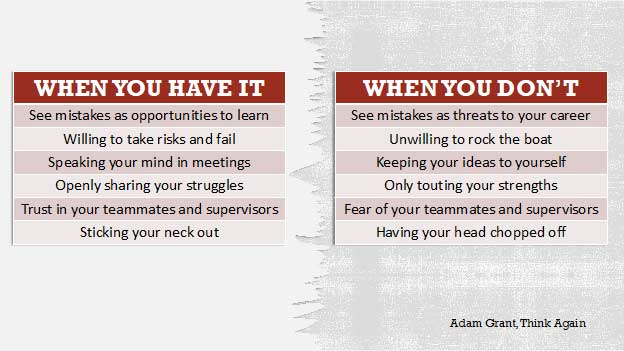

If there was one factor to be blamed for the poor mental health outcomes of our responders, it would be a lack of psychological safety. Psychological safety is a concept first discovered by Amy Edmondson, as cited by Adam Grant in his book, Think Again. It can be defined as: a shared belief that it’s okay to take risks, express ideas, and concerns, speak up with questions, and to admit mistakes—all without fear of negative consequences.

Psychological safety focuses on shared goals rather than self-protection. While it sounds soft, it is a requirement for both learning and high performance. Psychologically unsafe environments are found in fire departments across our country; these are toxic cultures where members stay silent and off the radar to prevent long-term negative consequences. Such environments breed distrust and disconnection.

Adam Grant shared the below chart to help differentiate between psychologically safe and unsafe environments:

Grant goes on to stress that psychological safety does not consist of relaxing standards, making people feel comfortable, being nice and agreeable, or giving unconditional praise, but instead of fostering a climate of respect, trust, and openness. In such environments, participants can raise concerns and suggestions without fear of reprisal In a recent podcast, FDNY Chief Frank Leeb reminded us that: “[Firefighters] don’t need another friend, they need an officer who is going to lead them, train them, and keep them safe—they have plenty of friends.”

Psychological safety is the foundation of a high-preforming learning culture. In fact, a lack of psychological safety was considered a persistent problem at NASA and was cited as a key contributor to both the Challenger and Columbia disasters. The historic performance culture at NASA lead to pride and fear of admitting mistakes. Today, NASA has completely transformed from a performance culture to a learning culture, where people are encouraged to speak up and inclusion is a priority. All members of the team are empowered to speak up.

- Seven Trust Busters That Damage Your Team

- Captain’s Corner: Characteristics of a Bad Officer

- Don’t Be THAT Guy! From a Chief Who Was

- What Is the Culture of Your Fire Department?

Psychological safety is also a key requirement for mental health. When members work in psychologically unsafe environments, their defensives remain activated and they experience chronic fight or flight, which leads to reduced heart rate variability, a biomarker associated with PTSD, depression, and suicide. Low-grade activation of the sympathetic nervous system also results in chronic inflammation and increased rates of cancer.

Because scarcity and fear run rampant in performance cultures, leaders often recruit for cultural fits rather than cultural adds, and difference is viewed as a threat rather than the asset it is. Like Chief Rhodes shared in his opening remarks, I too have felt the mental torture that comes from not being able to contribute. While I worried that feeling came from a desire for credit or recognition, I have since learned that Maslow’s highest need is not self-actualization, but rather self-transcendence, or significance. Mattering is what matters for people—to know their life and their work was significant (Covey).

If we want to improve our organizations and protect the mental health of our members, we must transform the cultures of our organizations to that of learning and caring. Our leaders must embrace building cultures of belongingness, authenticity, and vulnerability.

In his book The Culture Code, Daniel Coyle explains that safety is the foundation on which culture is built. He found the most successful organizations described their relationships not as a team or tribe, but as family, and the pattern of interaction he witnessed for these successful organizations included:

- profuse eye contact

- lots of short energetic exchanges

- high levels of mixing

- few interruptions

- lots of questions

- intensive active listening

- humor

- numerous small, attentive courtesies such (“thank yous”)

The key to creating psychological safety is recognizing that our primitive brains fear social rejection, especially from our higher ups. Overcoming this requires consistent signals of belonging, not just from our peers, but from our leaders as well.

Researchers from Yale, Stanford, and Columbia found that the magical feedback that leads to high performance and belonging was phrased in the following way: “I’m giving you these comments because I have very high expectations and I know that you can reach them.” (Coyle.) These 19 words powerfully expressed belonging and high expectation that predicted performance.

In the book Cultures of Belonging, Alida Miranda-Wolff shares that retention was highest in organizations where people had fulfilling, gratifying, and enjoyable day-to-day experiences, even if they faced traumatic events, low pay, or lack of benefits.

When leaders model vulnerability, they increase the psychological safety of the organization. We have evolved far beyond “because I said so” leadership. The burden on improving organizational culture and employee engagement rests on the shoulders of those in leadership roles.

“Leadership is not a license to do less; it is a responsibility to do more. And that’s the trouble. Leadership takes work. It takes time and energy.” (Sinek, pp. 286-287.)

Furthermore, leaders must engage to learn how they can lead better. As cited by Covey, Laszlo Bock recommends soliciting feedback by asking:

- What is one thing I should continue to do?

- What is one thing I should do more often?

- What can I do to make you more effective?

In his work, Chief Frank Viscuso recommends that leaders ask the following: “What should I start, stop, and-keep on doing?” By soliciting this sort of feedback and using it, you are communicating purpose and connection to your subordinates.

When you become a leader, it is no longer about you, it is about the people you lead. If you can’t see that your responsibility is to the people you lead, their performance, and their happiness, you are a toxic leader. The burden of firefighter mental health and wellness falls on our leaders. This starts with creating cultures of belonging, inclusion, and engagement. It’s also about remembering that leadership is a privilege, and the cost of this privilege is recognizing it’s not about you, but it’s about all those who you have the honor of leading.

REFERENCES

Brown, Brene. Dare to Lead. Random House, 2018.

Covey, Stephen M.R. Kasperson, David. Covey, McKinlee. Judd, Gary T. Trust & Inspire: How Truly Great Leaders Unleash Greatness in Others. Simon & Schuster, 2022.

Coyle, Daniel. The Culture Code: The Secrets of Highly Successful Groups. Bantam, 2018.

Edmondson, Amy C. The Fearless Organization:Creating Psychological Safety in the Workplace for Learning, Innovation, and Growth. Wiley, 2018.

Grant, Adam. Think Again. Penguin Publishing Group, 2021.

Junger, Sebastian. Tribe: On Homecoming and Belonging. Grand Central Publishing, 2016.

Miranda-Woff, Alida. Cultures of Belonging: Building Inclusive Organizations that Last. HarperCollins Leadership, 2022.

Sinek, Simon. Leaders Eat Last: Why Some Teams Pull Together and Others Don’t. Penguin Publishing Group, 2017.

Stanley, I.H., Hom, M.A., Spencer-Thomas, S., & al. (2017). “Examining anxiety sensitivity as a mediator of the association between PTSD symptoms and suicide risk among women firefighters.” Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 50, 94-102.

Dena Ali is a battalion chief in the Raleigh (NC) Fire Department with 15 years of service. She has a master’s in public administration from the University of North Carolina at Pembroke