by NICHOLAS DeLIA

This is a follow-up to “It’s Not Easy Being ‘Small’ in the Fire Service” (Volunteers Corner, Fire Engineering, January 2020) in which I dealt with many issues that small volunteer, combination, and career departments must address to be successful. Success means meeting some standard and delivering the best service possible to our customers. Any process used to determine our needs and opportunities requires a risk assessment, in which we should raise issues about which we need to evaluate our ability to provide the needed services.

In addition to the traditional reviews of response data, anecdotal experiences, and so forth, we need to dive deeper when evaluating potential high-risk/low-frequency (HR/LF) events, incidents outside of your common responses. You need to do research to prepare for these events. Many communities have developed other reports or plans for conservation, development, or right-to-know missions.

RELATED FIREFIGHTER TRAINING

- What Makes a Successful Fire Department Successful?

- Responding to “Routine” Incidents at Large-Event Venues

- Event Planning in a Downtown District

The local emergency planning committee (LEPC) has had responsibilities since the creation of the Superfund Amendments and Reauthorization Act. This requires that you evaluate your community for hazardous materials and specific reporting to the LEPC, which is an opportunity to plan for potential issues. The community’s plan of conservation and development usually addresses new or planned expansion of industrial facilities. Many commercial ventures will look for open space where there is a low population as a financial risk prevention approach. Unfortunately, because of the remote locations, they also have low responder numbers.

Risk vs. Hazard

A risk is the possibility of a loss or injury to someone or something that creates or suggests such a hazard. A hazard is a source of danger; the effect of unpredictable, unanalyzable forces in determining events; or a chance event. Once you create your list of risks and hazards, you can begin planning to handle/mitigate these issues.

A quick community risk reduction (CRR) message here: You may need to use the engineering concept of the Five Es (education, engineering, enforcement, economic incentives, and emergency response) to reduce your risk. As a proactive concept, develop a close relationship with your building official, who can warn you of potential risks during and after construction. Annual inspections or CRR enforcement concepts can prevent bad things from happening. When you have limited resources, you must do everything you can to prevent incidents.

HR/LF Incident Types

Some HR/LF events come to us from national trends or local tragedies, such as the need for rapid intervention teams or self-rescue skills. Others come from the very nature of our geography—e.g., 50 percent of our community is surrounded by water, including navigable marine ports, marshes, and tidal ponds. Some come from the local industrial base.

One of our largest employers builds submarines. Its facility has huge open space structures for this; the facility has multiple cranes and confined spaces. The industrial firefighters are experts when working with cranes for rescues. In your community, you may have a chemical or pharmaceutical research facility. We found those response personnel to be experts in their products and very well-versed in hazmat operations and advanced metering.

After 9/11

Following the 9/11 tragedy, additional risks fell into the fire services venue. Terrorism and the potential for structural collapse or urban search and rescue (US&R) emergencies are now under the fire department’s purview. Local airports were required to have plans, but that effort expanded exponentially after 9/11. In the “it’s not easy being small” world, these and other threats can be downright scary.

Many times, the department that owns the hazard has done some initial planning. Unfortunately, that may be where it stops because of the “it’s never going to happen here” attitude. I guarantee that if it does happen in your community, before the ink dries on the incident report or you get a chance to look at Facebook, someone will be looking for the emergency plan and the last time it was practiced or at least be asking those questions.

Successful plans expand to involve the mutual-aid partners, a plan for potential challenges, and for things in the plan to go wrong. To quote General Dwight Eisenhower, “No plan survives first contact with the enemy.” In some regions, individual departments have adopted a particular problem and have made the initial investments in training and equipment. Some do not have a choice; the risk is just part of their community or industry.

Below I will share a few examples of how it’s possible to develop a response plan when everyone can only contribute three to four members. In my small-town experience, you only survive by doing your homework, asking for help, and developing an appropriate plan. I would suggest starting with issues that everyone is struggling with.

Traditional Mutual-Aid Resources

Firefighter Assistance and Search Teams (FAST)

In the late 1990s, a local interest developed in firefighter safety and survival—specifically, the use of FAST operations. The Groton Fire Officers Association set up a meeting for like-minded individuals to discuss creating a plan. A diverse group of personnel from most of the association departments of various ranks met and started planning. Everyone had the opportunity to contribute to the overall mission. They discussed the following topics and teams started working on them: minimum firefighter training levels; training level designations/identification; training/development programs; the minimum FAST equipment required; and standard operating procedures (SOPs) for activation, dispatch, and operations. A significant amount of time was spent over a year to create the FAST process and its operations.

For many reasons, including staffing, the Submarine Base New London Fire Department (SBFD) was the tip of the spear in responding as a FAST. It participated and led numerous trainings on FAST operations for the 10 community fire departments. On January 28, 1998, a briefing was delivered to the Groton Fire Officers’ Association and the SBFD FAST was added to all fires that had a second source confirming an incident. While the primary first team for FAST came from the SBFD, our experience mirrored the Phoenix experiments (“Rapid Intervention Isn’t Rapid,” Fire Engineering, December 2003): One team would not be enough.

The FAST training was delivered to all the departments in town and their mutual-aid partners. A key component of the program was the idea that self-rescue or teammate rescue could resolve the issue many times. A FAST was still activated to engage the victim.

The seed planted locally then began to dramatically spread regionally. Soon, several fire departments across eastern Connecticut were providing FAST responses to second source or working fires. Ultimately, when the National Fire Protection Association’s Training Technical Committee took up the issue, the Groton FAST procedures were the backbone of the standard.

We needed a way to identify those who had been trained in the programs. Our system had already developed an accountability system, which used laminated photo identification cards. In addition, the system was color-coded: a red bar for an interior firefighter or the highest certification, yellow for the highest hazmat level, green for the highest medical certification, and a blue bar indicating FAST-level training.

Everyone was trained to the awareness level. Those who would function in a team would receive basic and then advanced training. A minimum level of required equipment was also part of the program. The gear list included a self-contained breathing apparatus (SCBA) bag with mask and adapters (these were homemade kits, a precursor to today’s commercial sets); minimal disentanglement tools (wire cutters, wrist cinch straps, and something to cut with); a large-area search rope system; and some standard rescue equipment (saw, irons, stokes, and so forth). As the FAST movement evolved nationwide, additional systems and tools were added—e.g., the 2:1 pulley system and thermal imaging cameras.

The minimum FAST has four members. When possible, we would add additional members to the team.

A few additional key issues: Four to six people are not enough. The rapid intervention studies in Phoenix, which we recreated, showed you will lose two personnel for every 12 engaged for several reasons. Four to six people (one team) cannot handle large structures just because of the sheer size and internal characteristics. Our run cards built in additional FASTs on every other alarm. The incident commander (IC) can call additional FASTs at will based on conditions.

Once two or more teams are on a job, you should have additional resources there to support them. We would call an additional engine and truck with a FAST chief (the Firefighter Rescue Branch) to supervise these resources. If possible, the FAST chief should be from a department that supplies this service or be specifically trained. Preferably, this is someone with experience. In our case, the responding agency would send a qualified FAST chief.

For the advanced drills, we found it should take at least twice as long or longer to set up the drill than to solve it. Our drill team would spend hours building very complicated scenarios to stress the responding teams. It would not be unusual to have to rotate four to five teams to solve the problem. If you are just starting out and do not have personnel qualified to design and run advanced drills, numerous groups are out there that can help you.

Urban Search and Rescue

The 9/11 attack created the need for multiple special operations or HR/LF teams. Our FAST operations interest fed directly into the planning for structural collapse response. Whether from a man-made or natural disaster, structural collapse operations are full of risk and require specialized training.

In our community, we began by taking inventory of all the equipment organizations had that we could use for collapse operations. We used the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) US&R team’s inventory as a guide. Once completed, we listed the items missing. Over the next few years, the departments that could purchased the missing items.

As we completed procurement, we undertook two additional projects. First, we brought in vendors, certified federal US&R members, and state fire academy instructors to conduct training; local members also traveled to national training events. Second, we conducted an Incident Command for Structural Collapse seminar for the local command staffs. The communitywide plan developed was similar to that of the FAST operations. Individual departments would conduct risk assessments for their local hazards and build a response or run card. If the event was large enough, they could request additional alarms, individual units, or a rescue task force. Many just built very robust cards calling multiple rescues. Multiple partners bringing additional equipment would act as one rescue response unit.

Just recently, because of regional risks and resources changes over the past 20 years, the Connecticut Region 4 Emergency Planning Team (REPT) initiated a review of the regionwide capabilities for Regional Emergency Support Function #9 USAR. Region 4 covers all eastern Connecticut up to the Connecticut River.

Hazardous Materials

Since the late 1980s, the SBFD had provided regional hazardous materials services. In the early 1980s, after additional assessments, southeastern Connecticut chiefs decided to create a regional hazmat component to back up the SBFD and protect various target hazards. The Connecticut Eastern Regional Response Integrated Team (CERRIT) was the result. The team included members of volunteer, combination, career, industrial, and tribal nation fire departments. Again, each member department would supply three to four trained members to create a full hazmat technical response team.

It started with a strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats analysis and creation of subcommittees on administration/policies, resourcing, tactical SOPs, equipment/technology, training, emergency planning, and logistics, to name a few. The team eventually developed a Region 4-wide tiered response system. A request from an incident IC would result in a response of one to two teams based on the location.

The initial CERRIT officer on scene would then make recommendations to the IC regarding upgrading the response. If the response was elevated, it would bring three to four more micro-teams, a dedicated technical decontamination unit, and a planning component. If needed, the entire group could be recommended.

Over the past couple of years, a duty officer was added to determine the best response profile. The team would routinely work with the Connecticut Department of Energy and Environmental Protection at incidents. Eventually, the team received support under the RESF 10 Haz-Mat line item. This pays for training, new equipment, and general team sustainment.

Multidiscipline Resources

9/11 and the creation of the federal Department of Homeland Security (DHS) provided an opportunity to enhance public safety. The REPT, consisting of the region’s elected officials, would determine which entities would receive funding for regional emergency support functions (RESFs). The following teams were created or upgraded under this system.

Incident Management Team. In 2000, ships from all over the world visited the port of New London as part of the OpSail 2000 global tour. This event challenged the region on multiple fronts including emergency response. The Federal Bureau of Investigation took the lead and coordinated, planned, and published a new document, the incident action plan (IAP). The port and general navigable waterways surrounding New London harbor bordered multiple jurisdictions, each with its own emergency responders. In addition, it incorporated access to Submarine Base New London and the eastern end of United States Coast Guard (USCG) Sector Long Island Sound. As a result of the increased risk, multiple mutual-aid units for all disciplines were incorporated into the five-day event and fireworks extravaganza.

Although the celebration with more than a million people in attendance was successfully protected, a couple of issues arose. First, multiple, large-scale incident command systems (ICS)were used independently throughout the overall sites. Second, there were no simple communications systems to use across and around the overall venue.

Several years later, Connecticut was awarded the Top Officials Exercise 3 (TOPOFF 3) to be held in April 2005 in the same area. This antiterrorism drill encompassed both sides of the Atlantic and Canada. At the same time, the CERRIT Planning Subcommittee had begun exploring the original concept of incident support teams, now known as incident management teams (IMTs). Because of the experience of many of the regional leaders involved in the CERRIT, an IMT was spun off to assist in a mutual-aid manner as needed.

This is an important detail; to this day, the IMT does not take over the scene. Instead of having the local jurisdiction sign over control, our document specifically states that we are providing mutual aid and the local authorities are still in charge. The TOPOFF 3 event training funds provided a significant foundation for the team. The initial training involved fire officers from New London County and from the entire state.

This class eventually spun off multiple regional teams. In addition, this effort engaged our USCG and military colleagues. The USCG, home of maritime ICS, and FEMA provided national level training to all involved.

OpSail 2000 was a benchmark event for the group. In addition to initial IMT on-scene support, at 2000 hours of the first night, Command transferred to a local National Guard Armory, the Joint Operations Center. The local IMT would provide services and IAP development 24/7 until the end of the event. A Joint Information Center was also in place throughout the event.

Over time and after additional activations, it became apparent we were not adequately multidisciplined for the times. The group set out to include law enforcement, emergency medical services (EMS), emergency management, and telecommunicators. At its largest point, the team had four diverse sets of 10 members each, each with a team leader. Over time, however, members were promoted, retired, or lost departmental support for extra activities. The group is down to about 20 but routinely assists as needed. For example, during the start of COVID-19, state emergency management used team members to track and document equipment distribution among other tasks.

RELATED FIREFIGHTER TRAINING

- Developing a Successful Approach to High-Risk/Low-Frequency Events

- Preparing for Low-Frequency/High-Risk Events in Small Departments

- Improving Outcomes for a High-Frequency, Low-Risk Patient Group

After the TOPOFF 3 experience, we set up our first unified area command for the annual Sailfest celebration and fireworks in July 2006. This event brings thousands of visitors to the greater New London/Groton area. The team was provided a large space at the New London Fire Department (NLFD) headquarters, located in the middle of the main venue. The operation was divided into the New London side, the Groton side, and the maritime/port exposures. The unified command team, the emergency leadership representatives of the two communities, and USCG Sector Long Island Sound participated in each of the subgroup’s briefings in person. In the unified command center, all emergency responder representatives and the IMT were present. This unified approach was a success in its first year.

The associated fireworks show draws hundreds of thousands of spectators both on land and sea. During the show, a patient at the far end of a long cement pier was suffering chest pain and required assistance. The assigned NLFD EMS foot patrol team had to battle their way to the patient through the 3,000 to 4,000 revelers on the pier. The team officer quickly deduced the assigned ambulance team would be unable to get the stretcher to the patient. He had already reported his difficulties during his size-up.

As the assigned team strategized what to do, the unified command developed a solution. The IMT planning section convened a quick meeting at the unified command center; working as a team, they found a solution. A 25-foot fast boat from USCG Station New London, already assigned as part of the Marine Group on the New London side of the exclusion zone, was reassigned to meet with the New London EMS walking team and the assigned medic pier side.

The patient was lowered onto the boat, which shot back down the river to the USCG station. An ambulance from outside the venue had been sent to the station to transport the patient to the hospital. A Department of Environmental Protection conservation officer met the transport unit at the station and provided a code three escort to the hospital.

Total time, from 911 call to hospital bed, was 18 minutes. The team would have had to battle their way through a packed crowd just to get the patient to the ambulance; the ambulance would have had to fight its way to the hospital. The ability to have conversations in a well-lit, air-conditioned, and quiet space is critical at such a large event. The planning section and command team came up with a creative solution to make this emergency response a success.

Marine Group. Various agencies up and down the East Coast have some form of marine emergency assets. For many years, agencies assisted the USCG in protecting the aforementioned fireworks shows. The law enforcement RESF 13 inherited various teams. Many police departments had some sort of marine craft. During the Marine Group’s creation, they were the simplest to upgrade. Vessels with suppression capabilities soon followed.

Equipment was just the beginning of the challenge. Planning had to follow the concepts of the various teams already in existence. Similar to the US&R challenge, equipment, communications, training—including formal navigation training, dispatching, and operational policies—all had to be upgraded or created. Fortunately, there has been funding for both new equipment and sustainment of the other gear.

The REPT also supports full-scale drills. This group has one of the more nontraditional participants. It includes the U.S. Navy, industrial facilities, commercial transportation ferry systems, and private salvage enterprises.

Marine operations can be tricky. For example, it’s one thing to take a patient off the deck of a recreational sailboat or motorboat; it’s another to take the patient off the deck of a vehicle-carrying ferry that’s 15 feet above the water line. The USCG has supported the program and continues to encourage the effort.

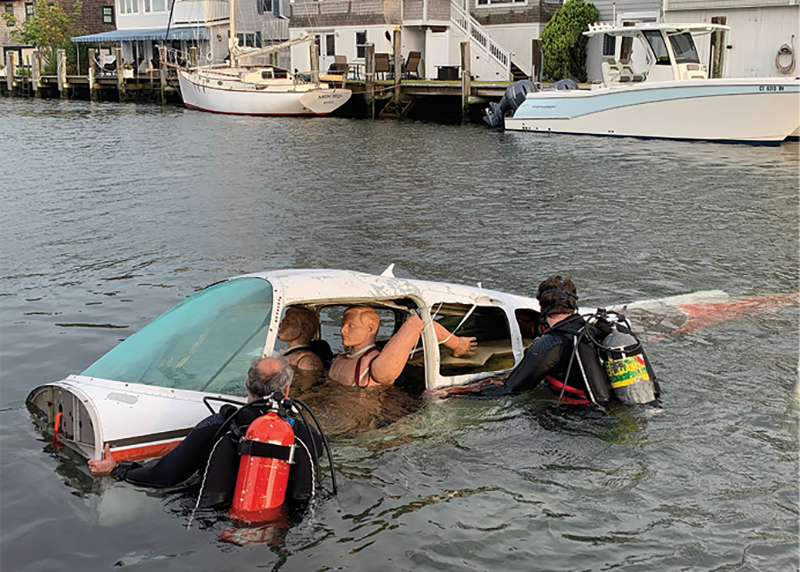

All these participants bring some form of support or equipment to the event. Again, you can get underway with a couple of personnel if you know others are coming to help (photo 1).

(1) A Marine Group rescue training exercise with plane prop. (Photo by Anthony Manfredi.)

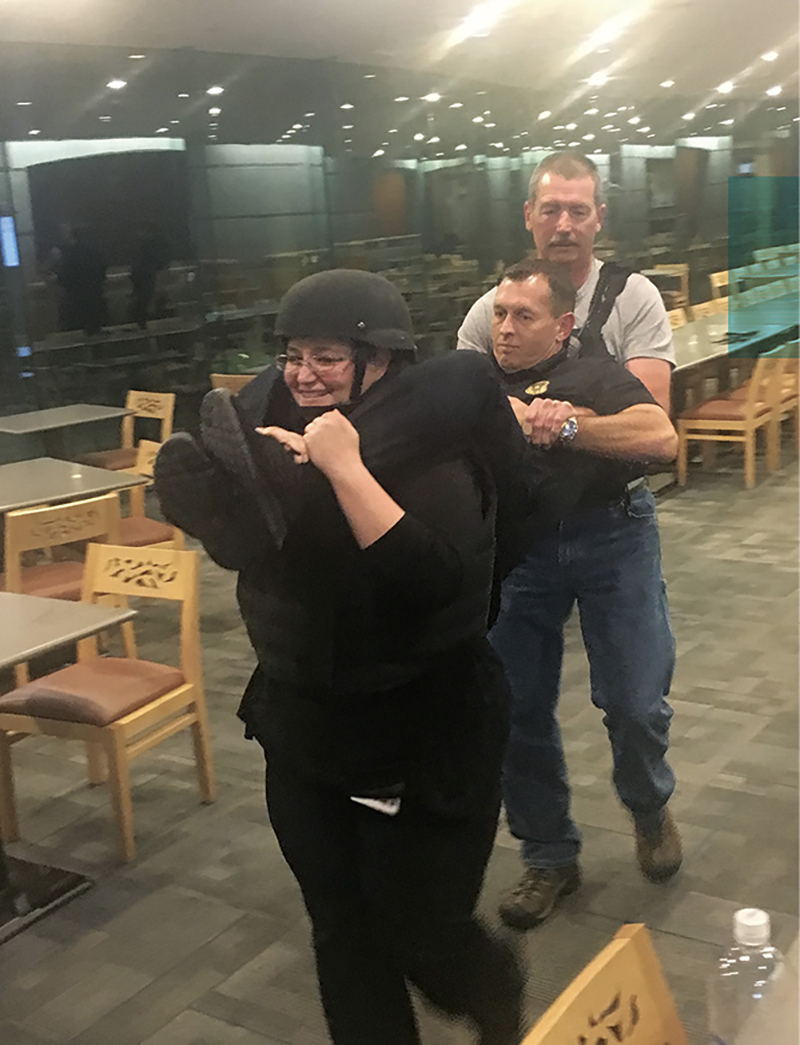

Dive Team. A natural segue from the regional marine group was the regional dive team. As with the marine group, the dive team was added to RESF 13’s responsibilities. Fortunately, most of these groups were part of the marine group infrastructure already. A few fire department teams had to be added to the group. As with all these groups, they are all personnel-intensive and have high risks. At this point, the REPT and regional emergency leaders are very skilled in forming teams. The process and activities mentioned above were all followed (photo 2).

(2) Initial Cold Water Team operations for a reported submerged car. [Photo by Old Mystic (CT) Fire Department.]

Active Shooter Response. As with most of the nation, the shooting at Columbine High School created a significant interest in active shooter situations for police departments statewide. The Law Enforcement Council (LEC) in southeastern Connecticut added an active shooter component to its annual certification requirements class, delivered principally in Groton. Three years after its inception, every patrol officer in the LEC and some state troopers had been through the active shooter segment. During this time, Hartford Hospital released its research regarding traditional active shooter tactics, lockdown and wait for tactical teams, and a new task force tactic that attempted to stop the violence and be ready to provide rapid live saving techniques. This new concept included today’s task force concepts commonly used across the country.

The LEC’s executive director contacted several senior IMT members. He had made a couple of observations:

- The fire service routinely moved multiple-person units around at emergencies and kept track of them.

- The fire service routinely called for and managed adding multiple mutual-aid units to operations.

- They understood unified command.

The task force concept was not an easy sell; traditional unit or company concepts do not work in police cruisers with a single officer.

Firefighter/EMS safety was the most serious issue to address. How do we protect fire/EMS workers throughout eastern Connecticut and the entire state, for that matter? Again, the RESF 13 team rose to the occasion and set up a system to distribute ballistic personal protective equipment (PPE) throughout the region, principally around target hazards and then among the remaining communities regionally. In addition, it created bleeding control kits and distributed them with the PPE. It set up bulk crisis bags (ballistic PPE and rapid treatment bags) geographically to supply requesting units during an incident.

It developed and delivered a multidisciplinary training program and continues to do so throughout the region. The class includes the basics: the active shooter history, tactical movements, Stop the Bleed® control, advanced tactical treatment techniques training, unified command, and a practical application. In addition, full-scale exercises have taken place at various target hazards. Fortunately, we have not had to deal with a large-scale event (photo 3).

(3) Practicing a victim carry variation prior to a full active shooter drill. (Photo by Timothy Main.)

Plan Ahead, Train Ahead, Call Early, and Call Often

The basic concept is as follows: If you can create relationships and bonds with your mutual-aid neighbors and fellow emergency responders, you can develop programs even with small numbers. It’s not easy being small, but you’re not the only one in your area who feels that way. Together, you can make it happen.

Reference

Kreis, Steve. “Rapid Intervention Isn’t Rapid,” Fire Engineering, December 2003. https://bit.ly/3KEIkWp.

NICHOLAS DeLIA is a 40-plus-year fire service veteran and the chief (ret.) and fire marshal of the Groton (CT) Fire Department. He is certified as a Connecticut state fire officer IV, fire instructor II, safety officer, and hazardous materials technician. DeLia has also served in leadership roles in state and regional hazardous materials response and urban search and rescue and incident management teams. He is a senior fire service consultant for JLN Associates and a contract instructor for community risk reduction programs at the National Fire Academy. DeLia has a BS in fire service administration from Empire State College.