VOLUNTEERS CORNER | By Richard Ray

The volunteer fireground faces many challenges. These challenges range from having enough firefighters on the fireground to coordinating the fireground. Having enough resources on the volunteer fireground is the linchpin for many volunteer fire departments when it comes to completing fireground tasks.

Richard Ray: Engine Company Excellence for Volunteer Firefighters

Without the proper resources and staffing, civilian and firefighter safety becomes compromised along with an increase in property damage. But firefighter safety is about more than having enough firefighters; firefighters must work under a command structure, and they must be accounted for while operating on the fireground.

In many cases, the incident commander (IC) is multitasking, and no one is tracking where the firefighters are operating. This kind of scenario is problematic and related to the reason that the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) has identified five factors that contribute to firefighter injuries and death, better known as the NIOSH 5. These include the following:

- Improper risk assessment.

- Lack of IC.

- Lack of accountability.

- Inadequate communications.

- Lack of, or failure to, follow standard operating procedures.

This article will cover numbers 2 and 3: lack of IC and lack of accountability. How does a volunteer fire department that struggles with staffing an incident dedicate personnel to these two critical elements? The answer is complex.

Mixed Messages

As a volunteer firefighter, I have operated at many fires where the IC is trying to not only command the incident but operate the pump on the apparatus or conduct the water supply operation. I do not believe that such multitasking was what the fire department wanted; it happened out of necessity due to the nature of the incident and the resources on scene. Unfortunately, there was very little structure at the incident. The chief officer’s focus was on multiple areas of concern. All of this was a recipe for disaster.

I’m happy to report that luck was on our side, and we extinguished the fire. However, this doesn’t mean the incident went well. No one got hurt but the performance was not optimal either. Such luck can lead the IC to believe that operating in this manner is OK.

Then we have the accountability piece. Many chief officers will argue that it’s OK to operate in this manner—everyone went home and the fire went out, right? This is the very attitude that will lead to civilian or firefighter injury and death.

In 2019 a small department in Illinois suffered a line-of-duty death and three other firefighters suffered injuries while operating at a house fire. The report from the Illinois Occupational Safety and Health Administration cited no unified command. The contributing factors were that the IC could not easily be located and each department maintained its own accountability for the incident. This is just one example of an incident turning tragic when personnel on the fireground must perform multiple duties while they try to command the incident and account for personnel.

Command and Control

It is no secret that utilizing the IC system at an incident is critical to the success of the incident and to the safety of personnel operating on the fireground. Many volunteer fire departments do command and control well. Those departments typically have the personnel to fill all the fireground functions. But what about the smaller volunteer or rural departments? How do they ensure command and control on the fireground when they have other critical functions to address? It is a balancing act at best.

It’s important to remember there’s no silver bullet here, and every department must start somewhere. The process begins with ensuring that the chiefs and line officers have command and control training. The National Incident Management System (NIMS) is a great place to start. (You can find many online classes as well as in-person classes on this.)

NIMS training provides officers with the foundation of the IC system and how to structure it. The training must progress from here. Once this basic training is accomplished, the department’s officers can then apply it to their respective organization.

At this point, the officer brings previous training and experience together with NIMS. With that in mind, he should have a very clear understanding of the fireground benchmarks.

From here the department should use the IC system on all calls—even the most basic calls. This practice will provide the officer with the necessary repetition to build his skill set in commanding an incident so that when a larger incident occurs, the officer understands how the incident should flow. The officer should also learn the importance of prioritizing tasks.

All of this will help officers develop a bigger-picture mindset rather than having them focus on individual fireground tasks. It will also help officers learn how to deal with—and control—freelancing firefighters.

Lastly, the repetition of using IC on all calls can give an officer an opportunity to make decisions. I have seen volunteer officers afraid to make decisions or fail to make decisions. Decision-making ability comes from fireground experience coupled with an understanding of the IC system. As an IC, the volunteer officer should have the courage and ability to make tough decisions. The safety of the citizens and the firefighters depends on it.

Standard operating guidelines (SOGs) should identify who the initial IC will be. From there, command is transferred or retained. This will aid the first arriving officer/firefighter in building the fireground while ensuring control of it. If command is transferred, it usually goes to the higher ranking or most senior officer. However, if you are the higher ranking or more senior officer and the individual who has command is doing a good job, then allow him to continue. This is a great opportunity to provide an officer or firefighter with much-needed experience. In your department, depending on how many personnel you have on scene, this may not be plausible. Still, when possible, never deprive a young officer/firefighter from command experience, especially if you have the opportunity to shadow. Lastly, the location of the IC should be identified in departmental SOGs, and the IC should be in a position where he can see the incident.

When you’re in command, command the incident. To command the incident, the IC should have operational awareness, which is the ability to understand fireground activities to make informed and timely decisions, allocate personnel and resources, and respond to the dynamic incident. Operational awareness is critical; the fireground requires rapid decision making and adaptation to changing conditions. The IC should have a very clear understanding that the decisions made on the fireground come with risk. The IC should know how the decision will impact the incident at the moment it is given and what the downstream effects will likely be.

When you’re giving orders, use a standardized delivery method. This approach provides clarity, consistency, and efficiency when you’re on the fireground. Ensure that the personnel receiving the order acknowledge the order. So, for example, “E3 from Command.” “Go ahead, Command.” “E3, fire attack first floor.” E3 copies, “Fire attack first floor.”

This is a simple yet effective way to communicate an order that can ensure the personnel understand the assignment without taking up critical airtime on the radio. When you’re giving orders on the fireground, you should understand reflex time. This is the time it takes to complete a task from the time the order was given. This is also where the IC should be poised and patient with a solid understanding of how long it will take to complete fireground tasks. This can be really challenging for the IC because on an incident, seconds feel like minutes and minutes feel like hours.

A strong IC is critical to the success of the fireground and to the safety of the firefighters. ICs should keep things simple and focus on known facts. Maintain constant vigilance of the firefighters operating. Understand the capabilities and limitations of your firefighters so that you can assign them to the appropriate tasks. This is extremely important with volunteers, as not all volunteers are interior firefighters. Much like their career counterparts, volunteer officers should understand and know the art of commanding the fireground.

Accountability

A major responsibility for the IC, accountability is defined as a system that tracks the location of firefighters operating on the fireground, specifically in the hot zone of an emergency scene. In the volunteer setting, this can be super challenging, depending on what type of accountability system you are using and the amount of training that is conducted on the accountability system. Most volunteer departments use some form of an accountability system, but does the accountability system your department is using truly account for members operating on the fireground or does it take attendance? There is a big difference between the two.

Having accountability of personnel operating on a volunteer fireground can be challenging. It is difficult to keep track of personnel who arrive in privately owned vehicles (POVs) at different times during the incident. To help organize the response, the IC must have control of the fireground. All personnel, whether they respond by POV or on an apparatus, should report to the IC.

Some form of a staging area should also be created, but this comes with challenges. In some areas, staging is nonexistent because there is a struggle just to have enough personnel on scene to complete the fireground benchmarks. On arrival at the scene of an incident, all personnel should always check in with command. This allows command to know who is on scene, and it allows the IC to assign the tasks. However, I have also seen instances where volunteer firefighters show up on the fireground and go straight to work without checking in with command. This freelancing causes problems, not solutions.

What type of accountability system does your department use? Some systems are simple, such as a tag system (photo 1). Here, the firefighters have tags that hang from their gear/helmets. When they arrive on scene, they place their tag on a hook. This is usually on the first apparatus. This type of system is better than nothing but, ultimately, this system simply takes attendance and does not track where the firefighters are operating.

1. Photos by author.

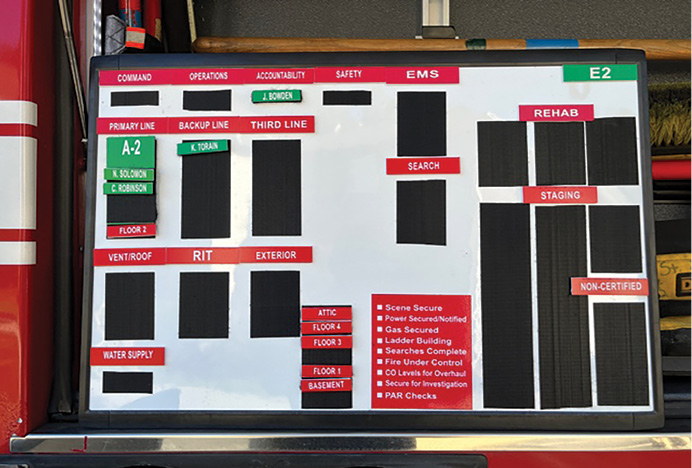

Many fire departments have moved from the tag system to a passport-style system (photos 2, 3, & 4): Firefighters have tags that go on a passport that rides in the apparatus. When they get to the fire, the passport is placed on a board (photo 3). This works great when the rig is staffed from duty crews or simply has enough firefighters riding the apparatus. This is a cost-effective way for a department to have an accountability system.

2.

3.

4.

With today’s technology, you can also set up an electronic accountability system that can be used with a tablet (photo 5). This type of system costs more. But if your department is tech saavy, it may be a good option—especially if your department uses a duty crew and has a tablet for the mobile data terminal. One challenge associated with this technology is that many parts need to work together, such as CAD and your records management system.

5.

All of these systems have pros and cons but for the IC, the best way to conduct accountability on the fireground is to use a formal system along with someone who is dedicated to fulfilling this fireground function. Many volunteer fire departments may be able to use a member who is not an interior firefighter. This is a great way to engage this member with an important job.

The Bottom Line

Having a good accountability system is critical when the rapid intervention team (RIT) must be deployed for a Mayday situation. If your accountability system works and the firefighters are using it appropriately, it should help with identifying down firefighters and their locations while simultaneously reducing the time it takes the RIT to get to them.

It cannot be overstated that command and control, paired with accountability, can go a long way in building a safe and efficient fireground for firefighters. For volunteer fire departments, it is even more critical, simply due to the nature of how those fireground operations can go based on when and how firefighters arrive.

Avoid becoming a statistic. Make sure your mutual aid understands the importance of the command and control. And be sure to have an accountability system that works between departments. Due diligence is critical, so train on IC and accountability before an incident happens. Ensure that all personnel—firefighters, lieutenants, captains, and chiefs—all understand the importance of IC and accountability. Their safety depends on it.

RICHARD RAY is a 32-year veteran of the fire service with both volunteer and career experience. He is a career firefighter with the Durham (NC) Fire Department, where he serves as a battalion chief and an adjunct instructor for the training division. He is a member of the Creedmoor (NC) Volunteer Fire Department, where he serves as a firefighter. He instructs at the national level and is a member of the FDIC International Advisory Board and the UL FSRI Size-Up and Search & Rescue Tech Panel.