HURRICANE ANDREW: A PERSONAL ACCOUNT

Monday, August 24, 1992, (0530) has now been recorded as the day of the most costly natural disaster in U.S. history. Hurricane Andrew was not the “hurricane of the century,” as anticipated by the educated and experienced few. In fact, Andrew was the third most powerful storm to strike the f.S. mainland; Camille (1969) and the unnamed Labor Day storm that struck the Florida Keys in 1935 were officially stronger storms.1

My personal account of the hurricane doesn’t provide mountains of statistics, numbers of alarm dispatches, and the response totals of numerous and varied pieces of fire-rescue apparatus. My intention is to share our department’s experiences prior to, during, and after the hurricane and perhaps, more importantly, to describe the post-hurricane impact on our department and personnel.

Most fire/rescue departments operate on an around-the-clock schedule to maintain constant and, hopefully, sufficient staffing of emergency response apparatus and equipment.

While this puts fire/rescue departments at some advantage operationally, history tells us we quickly can outrun our fuel and supplies if there is a weak support and communication network.

My perception of social factors — that is, the way Dade County society reacted to the hurricane —is emphasized. In no way, however, is any description meant to reflect negatively on the public servants, citizens, and visitors of the greater Miami area who performed countless acts of courage, made sacrifices, and made meritorious efforts on the day the hurricane struck and for months after.

PRESTORM ACTIVITIES

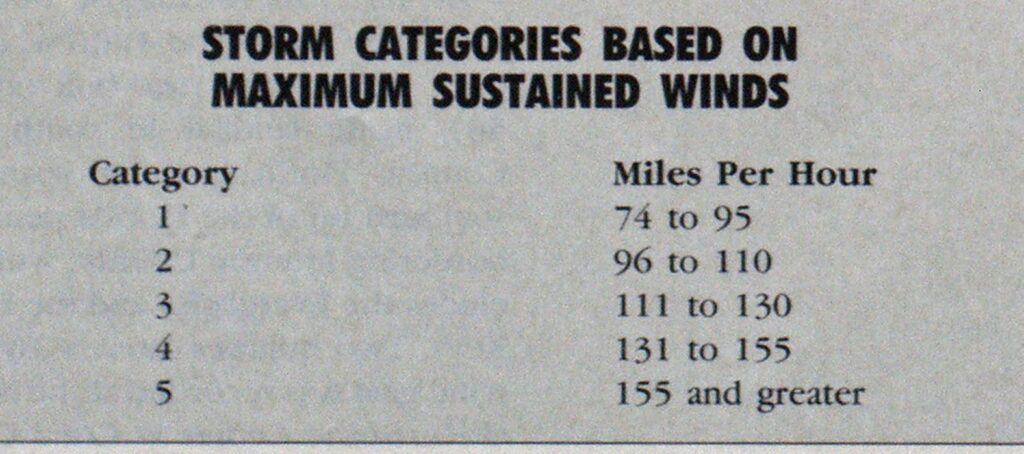

1 lurricane Andrew’ sprang up quickly in the eastern Caribbean. It moved quickly (at 30 mph), gaining strength and rapidly developing into a category t hurricane upon landfall. Andrew, prior to ripping the radar equipment off the roof of the National Weather Service building in Coral Gables, had maximum sustained winds clocked at 140 mph, with w ind gusts of 170 mph reported. The storm also had picked a weekend to “sight in” on the South Florida area, and many government administrators, department directors, and their staffs were being quickly contacted while they were in the middle of trying to secure their own homes and families, having psychological significance not only for these people who were called away from home but also for the city at large.

On-duty personnel were taking written SOP manuals off the shelves to locate the sections that would provide appropriate guidelines, such as the following:

- conducting “school” on Hurricane Warning Procedures with onduty personnel;

- securing window protection panels, loose furniture, equipment, and property;

- “sticking” and documenting fuel tank levels (order as needed);

- preparing forms for personnel who call in reporting their availability;

- securing and relocating apparatus/ equipment from stations within flood zones;

- reinstating radio communication roll call and message relay procedures; and

- activating and staffing the City of Miami Emergency Operations Center (HOC).

The list goes on and on.

We had this “prestorm” process pretty much down pat after some 20 years of “drill” (but no “real”) storms. Our department has continued to see years of experience go through the doors; in October 1991, nearly 10 percent of the department retired; with them went more than 1,800 combined years of experience.

Don’t misunderstand me—our people are well-trained, professional firerescue personnel, and they performed at the highest levels expected in the traditions of the fire service. However, they and the entire community were about to become actors, players, and, yes, survivors in “a big one.”

The reality is that our department has been working hard to hire people who reflect a community whose makeup is increasingly comprised of people born and raised in different regions of the country, or even outside the country. Subsequently, the storms of the sixties are distant childhood memories for most of our population, including me, or fuzzy remembrances of headlines and television accounts from across the ocean, straits, or gulf. Many of out department members were infants or small children in the sixties who now, after coming to assume that talk of “the big one” was simply people “crying wolf,” found themselves preparing for the “big bad wolf huffing and puffing and blowing the house in.”

(Photo by Justin Wasilkowski.)

(Photo courtesy of Coral Gables Fire Department.)

RESPONSE ACTIVITIES

We responded to alarms until about 0330 hours, Monday, at which point the winds made travel much too hazardous for fire/rescue personnel. The sunrise found fire/rescue apparatus surveying their first-alarm territories for damage assessment, roadway passagc/blockage identification, street signage, and hydrant location; helping to clear debris from doorways and alleviate hazardous positions; and providing any other needed services. We worked 36-hour shifts.

The response to this disaster by our department rapidly became more than just the normal after-storm calls for emergency services within our jurisdiction. We had a 300-percent, and then 200-percent, increase in response calls for the first and second weeks following the storm.

INDISCRIMINATE DESTRUCTION

After the storm, a review of our department’s 650-person roster found more than 180 personnel (nearly onethird) whose residences were damaged. They lived south of (below) the state road that runs east to west across Dade County, identified as the northern boundarv of the area of devastation. We found ourselves not only with on-duty people who were unsure of the status of their families and homes but also with off-duty people due to report to duty, for whom travel, or the capability to leave their families, was impossible.

More than 1,400,000 of the county’s two million residents were without power and 150,000 were without phones.2 We found we were without a communication network to even verify’ how our people were doing. Whether you were a newly hired clerk/tvpist or the department director (fire chief), “the big one” didn’t discriminate.

The massive power outages also affected the water system’s pump pressure and, correspondingly, the availability of water for potential fire suppression activities. Also, critical needs, due to the lack of electrical power, were of concern regarding food-storage refrigeration equipment. No power, no refrigerators or freezers, no chlorination for the drinking water—thus, no ice-producing capabilities— created unbelievable problems. People who were stunned, shocked, and dazed quickly became people who were hungry, thirsty, irritable, and angry. The Maslow “needs hierarchy” had fallen overnight to basic survival needs.

We mobilized special search and rescue teams (SRTs) using off-duty volunteers to staff reserve transport rescue units to initially search for our own, other city employees, family members, other emergency services, department members, or their families. The SRTs delivered food, water, baby supplies, and medicines to department employees. These efforts went a long way to help relieve some of the stress associated with not knowing how family and friends fared through the storm.

MEETING BASIC NEEDS

We developed a special logistics section under our support services division that quietly, but efficiently, tackled the acquisition of our most crucial of needs—water. Contacting nearby counties’ breweries and milkand liquor-producing companies proved to be a windfall. The Florida Dairy Association provided 12 stainless steel, 8,000-gallon tankers for water transport; private enterprises donated everything from cleaned and certified tankers normally used for alcohol transport to water packaged in aluminum cans. Tractor trailer/ transport companies were contacted regarding the pickup and delivery of tons of pallets with hundreds of bags of ice from as far away as New Orleans and Kansas City. The truck drivers were provided with food, bedding, and cleanup facilities and then were scheduled for pickups, drop-offs, and return trips.

The firefighter unions and benevolent associations from within our fire/ rescue department came to the aid and assistance of the employees and their families with organized work parties. After employees were located by the SRTs, their shelter needs were evaluated and they were placed on a list for follow-up by the organized work parties. These work parties did roof repairs, boardup, and just about anything necessary to get our people’s homes back to a manageable level. This was all in addition to our regular duty assignments. Several other organizations from within the department assisted with contacting personnel and securing temporary housing at the benevolent clubhouse and motels/ hotels outside Dade County for those who had completely lost their homes (15 percent of the department).

During the first days when small amounts (two or three gallons per household) of clean drinking water were delivered by the SRTs, we realized that water would in fact quickly become the most valued natural resource. Acquiring this basic necessity was one thing, but as we know in the fire service, moving it takes specially made trucks—tankers, to be more specific—and lots of them. Within four to seven days, the major assistance efforts to establish and maintain shelter for our own were well underway. Once we had addressed the basic needs of our own community, it was time to turn even more so to the survivors in the south Dade County area where the storm had made landfall and that had received the heaviest beating.

The special logistics section, which became known as the “Can-Do” team, secured and provided meals and beverages for all city and HOC workers, and the numerous staff of the city’s civilian personnel gathered and pressed into action. All were eager to help; many, understanding the seriousness of the situation, gave their resources free of charge.

LESSONS LEARNED

The myriad of involvements and activities requested by our clients after the storm went from clearing debris and stopping water leaks to addressing serious concerns for clean drinking water. The dynamics of human emotion and concern shifted as some needs were satisfied. Yet, it was observed that being without, or thinking of being without, basic survival needs such as water, food, and shelter easily can turn the most mild-mannered into fighting tigers.

Water and ice distribution sites were quickly mobbed by people who were pushing and shoving, many screaming that their particular situation justified their actions. Scheduling and coordination of police escorts and details were assigned to the semitractor truck and tanker units to provide protection and maintain order nearly a week after the storm.

Roadside piles or, more accurately, mountains (30 to 40 feet high) of storm-related debris piled up as people tried to remove the debris from their property. It was inevitable that some of this would serve as fuel for uncontrolled fires; reports of trash burning brought two pumper assignments and some required full building assignments. Eventually, the trash was carted away to controlled burn sites. As recently as the end of February, the department had one pumper staffed by overtime personnel overseeing the remaining burn site.

(Photo by Bill Glass.)

Watch towers like those used historically until the 194()s were needed. Permission from private corporation high-rise owners was requested and secured so that teams of firefighters could set up on rooftops and penthouses to monitor the horizon for possible fires. Several large trash fires (400 feet long) were spotted, reported, and subsequently extinguished through this strategy.

Three to four days into the poststorm environment, electrical service was restored to some areas. This is the period of time when fire/rescue responders must exercise special care. Many people are killed or seriously injured during this “recovery” period. Human spirit makes people want very much to get things back to normal; however, that task can be challenging. Wires which had lain still for days would suddenly jump to life as power was restored, energizing tree limbs, branches, and fences lying on homes, vehicles, and property.

We must never forget that people are the reason we are here and that people are the reason the job gets done. Preparation for impending tragedy is challenging; however, we must be ever mindful of and anticipate the basic needs of our people; their concern for their families and coworkers is a strong motivator. If these areas are acknowledged in writing in our “guides to thinking”and “plans for action”-type manuals and SOPs, we have gone a long way toward establishing a positive environment for our people, who must work in spite of the personal implications of natural and manmade disasters.

I would like to extend special thanks to Emergency Management Coordinator Captain Mike Corson for compiling after-action reports and for information and research assistance.

Endnotes

- Governor’s Disaster Planning and Response Review Committee Final Report, January 15, 1993, page 1. Tallahassee, Florida. Phillip D. Lewis, chairman.

- Ibid.