How to Step on Their Shoes Without Messing Up Their Shine

FEATURES

MANAGEMENT

Measure performance against mutually understood standards, and there will be no surprises during employee evaluations.

Performance evaluations aren’t easy for anyone involved. Employees want to be well thought of by others, especially their supervisors, so they’re apprehensive about being evaluated.

And supervisors have a long list of reasons to dislike conducting performance evaluations. Most people have a high regard for the feelings of others, and criticismeven of the constructive sort—is difficult to deliver. When criticism is necessary, an argument may be part of the bargain, since most firefighters consider themselves at least “above average” in job performance and resent their supervisors saying otherwise. Then there’s the tendency of many supervisors to want to appear as a “good guy,” the fear of union or informal group reaction, and the fact that deficiencies may seem insignificant compared with the risk of injury and death that every firefighter faces.

Yet, in my experience, most employees want feedback from their bosses regarding how they’re doing, A majority of employees request better supervisory guidance on work assignments and other job functions.

The goal for supervisors evaluating firefighters, then, is to find a way of “stepping on their shoes without messing up their shine.” Accomplishing this begins with recognizing the performance evaluation for the multifaceted tool it can be when properly conducted:

- Communications tool. The basic purpose is to tell the employee how that person is doing in the eyes of the boss. The evaluation should identify any needed change in behavior, skills, or job knowledge. It also is the basis for

- coaching, counseling, and future planning.

- Motivational tool. By stating the performances expected of the employee, the evaluation gives the firefighter clear-cut standards to meet. Because of the two-way communication involved in the process, it also enables the supervisor to understand the reasons behind an individual’s underachievement and help to change them.

- Recognition tool. Through the evaluation, the employee realizes that the department is aware of both underachievement and superior performance. The process also enables the supervisor to recognize management practices that may be inhibiting performance.

- Documentation tool. The evaluation becomes a permanent record of past behavior, both positive and negative, and a guideline against which to measure future behavior.

How do we accomplish all these things? First, by reducing subjectivity, and second, by developing a game plan that both supervisor and employee can agree on.

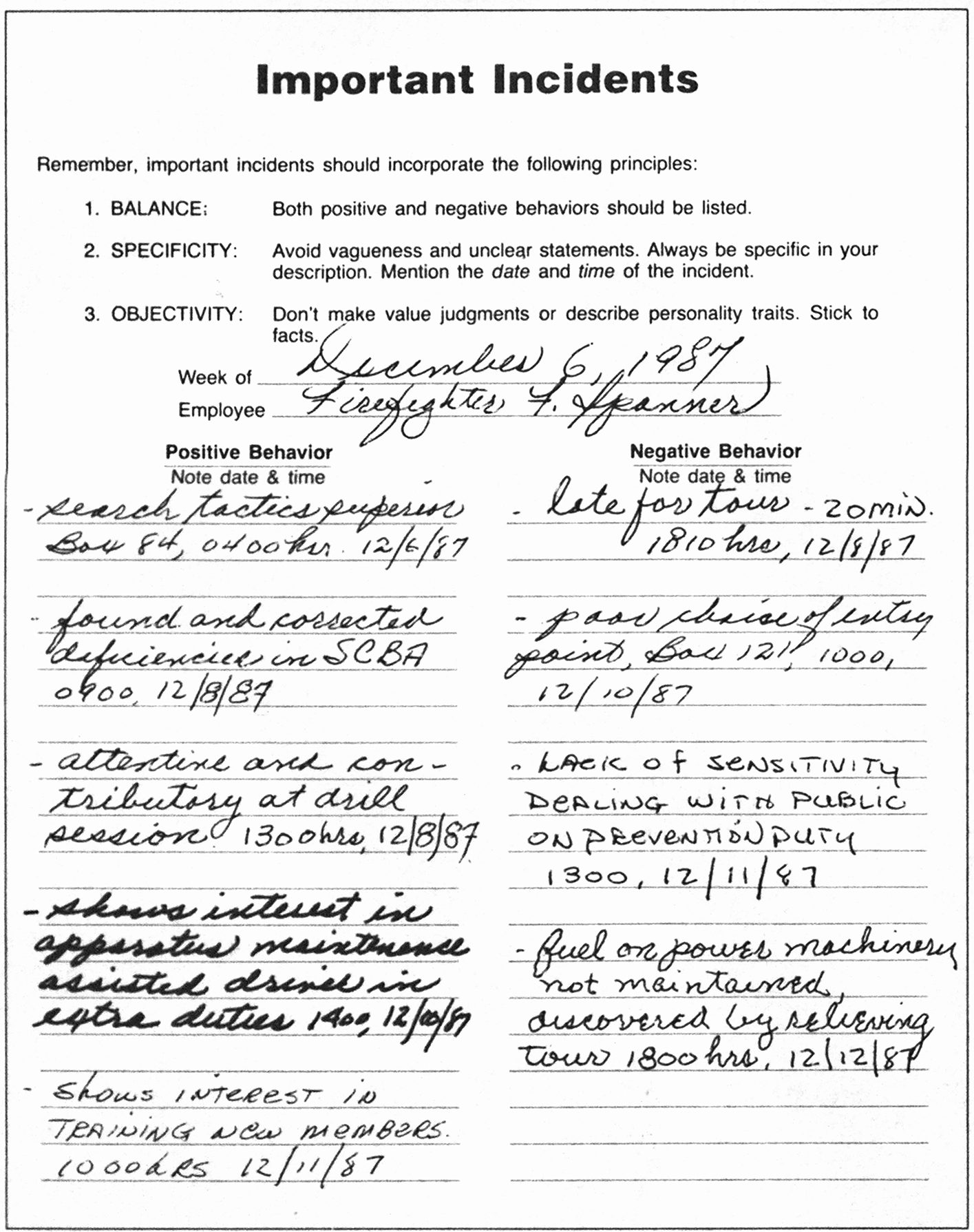

Subjectivity is minimal when, for each employee, the supervisor keeps a form documenting “important incidents.” (See figure above.) The form allows for documentation of positive and negative employee behavior, to help the supervisor recall specific actions, dates, and times when the employee has done something other than the ordinary. Properly filling out this form accomplishes two things: It requires the officer to continually monitor the employee’s behavior, and it identifies good behavior that’s too often quickly forgotten.

For example, when I first started using the form, I was surprised in most cases how long the list of positive behavior incidents became and how short the list of negative behavior incidents remained. Unfortunately, it’s human nature to quickly forget the good things people do and to forever remember the things not liked. This form reins in the negative tendency. When it comes time for the evaluation, the supervisor has specifics at hand.

That doesn’t mean that the first time the supervisor communicates with the employee about these behaviors is when delivering the written evaluation. Rather, the officer should discuss each incident with the firefighter before entering the items on the form. The evaluation process is continuous and ongoing; there should never be any surprises when the more formal evaluation takes place. This also forces the officer to orally compliment good behavior, something supervisors often neglect to do.

As noted, the evaluation process is a year-round format for supervisors and employees to work together to review, evaluate, and plan the employee’s job performance. It’s not just a fill-in-thesquares summary evaluation form that pops up on an officer’s desk once a year.

The performance evaluation program used by the Santa Monica (Calif.) Fire Department consists of three steps:

- Step 1—Initial meeting. The supervisor meets with the employee, and they discuss the employee’s job responsibilities as well as specific work behaviors. At this meeting, it’s necessary for both parties to reach an agreement on what constitutes a certain rating.

For example, an employee who never missed a day’s work and was never late in a year’s time might consider this behavior “outstanding.” On the other hand, the supervisor might believe it’s just part of the job and consider the behavior “satisfactory.” There’s a difference of opinion as to what constitutes a certain rating. Agreement ahead of time eliminates arbitrary value judgments, and all concerned are aware of the rating objectives.

This places the responsibility for the performance where it belongs—on the shoulders of the employee. The officer’s job is now easier because that person analyzes rather than appraises behavior. The employee either lives up to the agreement or does not; it’s as simple as that!

The supervisor does have responsibility, however, to discuss suggestions for helping the employee perform acceptably, and to let the firefighter know the officer’s help and support are available.

- Step 2—Periodic review. The supervisor and the employee meet as many times as necessary and useful during the year. At these times, the officer gives praise and reinforcement for good performance, and gives constructive feedback and guidance on responsibilities the employee might be having difficulty with. Supervisor and employee together revise and update the game plan when an employee’s duties or performance levels have changed.

- Step 3—Formal performance evaluation. At the end of the year, the supervisor gives the formal evaluation based almost entirely on the job responsibilities and performance goals that the supervisor and employee have agreed on. If the supervisor has kept up with the behavior documentation form and has been discussing the employee’s performance along the way, there should be no surprises.

This three-step process creates a relationship in which the employee takes responsibility for his or her own actions. The accent is on performance, not personality. With the emphasis shifted from “what you’ve done” to “what you’ll do,” the employee becomes an active agent in the process. The pressure is off the supervisor, making it easier to “step on thenshoes without messing up the shine.”