By Paul J. Antonellis Jr.

Change is taking place all around us. From an organizational standpoint, some of the changes being implemented will be successful; others will fail. In fact, organizational change is only successful 25 to 35 percent of the time.1

Change management can take many forms. It can involve a simple policy change, a procedural change, a personnel shift, an organizational change, or anything subject to change from a prior state. To minimize resistance to a change, the people who will be directly or indirectly impacted by it should be involved in the change process. The strategy used to implement the change is just as important as the change itself.

A number of factors can affect the success or failure of a change. This article focuses on how fire service politics and ethics can affect change management. Regardless of rank or number of years in the fire service, you at some point will be part of a change. Fire service members play a significant part in the change management process and in determining if the change will be successful.2 The change manager must consider those people who will be impacted by the change and the political culture within the department to ensure the success of the proposed changes.

CHANGE PROCESS

A number of textbooks have been written explaining the step-by-step process for change management. Some processes involve only a couple of steps, while others are very detailed and require many steps. In this article, change management focuses on the following three steps: (1) preparing for change, (2) managing change, and (3) reinforcing change. In each of these steps, politics and ethical practices can support the change process if it is managed properly. As noted, the change agent should not prepare for change without considering how the organization’s local politics surrounding the proposed change will affect the people the change will involve. Change is almost never a neutral status; it is going to affect someone in a positive or a negative way, and these people will respond to the change in different ways. It is important for the change manager to monitor the ebb and flow of the politics involving the change as he moves forward. As additional information becomes available about the proposed change and how it will impact organization members, political forces may shift or totally change. Failure to monitor these changes could lead to unexpected members’ resistance in the implementation phase.

The fire service has seen changes implemented immediately as a direct result of an outside force or demand.3 In these types of change cases, the department is responding to an outside force or demand, resulting in a reactive change process. What is often missing from the process is preparing for the change and managing the change. The immediate change is issued based on the outside force or demand. When a department is in a reactive status to change, resistance and resentment are often met during the acceptance period. An example would be an accident in which the driver backs into an object while backing up a motor vehicle; the department issues a new policy the next day stating that no vehicle will be backed up without a backup person to guide the driver. This would be a reactive change. The change was the direct result of an incident with no further input from the stakeholders (firefighters, line officers, training officers). It is often the stakeholders (those directly or indirectly impacted by the change) who will be able to provide the most insight into the incident and possible alternatives to bringing about a positive change.

This is not to say that every change in the fire service must undergo an extensive group process; rather, it is up to the leader or manager to determine what political and ethical impact the proposed change may have on the organization and to what extent the organization will resist the proposed change. When a leader or a manager can properly assess the level of resistance, there is a better chance that the change will be successful. Relying on your rank to bring about change will often create resistance, resentment, and often attempts to have the change fail. Individual or group members’ emotion-laden differences can create political power that can result in the failure of the proposed change.

On the other hand, a proactive change would involve a change made before an incident occurred or was dictated by an outside force, not in reaction to a situation. A proactive change can be managed over a longer period and involves additional stakeholders and the input from those directly or indirectly impacted by the proposed change. When the stakeholders feel that they have an opportunity to voice open, honest, and respectful communication on the proposed change, they are often more willing to accept the change and want to see it be successful.

There is a need for proactive and reactive change in the fire service. When immediate action is required for the change, stakeholder participation may not be the best approach for gaining commitment and reducing resistance to the immediate change. The emergency scene may be a good example, based on time and limited knowledge; the incident commander (IC) will need to make an immediate decision (change). The firefighters on an emergency scene know that the IC makes the call and the firefighters’ job is to carry out the task. Spend any time in the fire service, and you will always have someone second-guessing the on-scene decisions well after all the facts have been presented. Let’s face it: If the IC had all the facts and could look into the future, all of us would be better equipped to make the best decisions (changes). The lesson from this example is that the fire service must expect proactive and reactive change. Depending on the change, there may not always be enough time to involve the stakeholders in the change process.

RESISTING CHANGE

Some of the reasons for resisting change include the following: (1) fear of the unknown (the final results of the change), (2) not buying into or believing in the change, (3) concern about how the change will impact the members’ jobs, and (4) there have been too many changes too fast.4 The use of threats or punishments when there is opposition to the change often will be met with resistance,5 resentment, and members withdrawing from the process of change. Participation in the managing of change will never overcome the resistance to the change if the participation is only being used as a tool to force people into committing to the proposed change. Hence, involving stakeholders in the change process is only half the issue for providing positive change in the organization. The leader or manager should not use stakeholders’ participation as a means for forcing or bullying a change to the group; group members have to feel that the participation is based on open, honest, and respectful communication.

Some argue that employees will comply with the proposed change for extrinsic reasons (5); the extrinsic motivation may be to avoid being disciplined for not following the new change, or the firefighter may just go along with the new change to earn extra points with the administration. Determining a firefighter’s intrinsic motivation may be challenging. The intrinsic motivation comes from within the firefighter seeking an internal reward. Hence, the firefighter will be more willing to engage in a behavior that will bring about internal reward. Leaders and managers who can identify extrinsic and intrinsic motivation in employees stand a better chance at implementing positive change in the organization. Political pressure (extrinsic) from within the fire department culture can alter the behavior of an individual or a group of individuals when it comes to implementing change in the department.

Every fire department across the country has boundaries; the boundaries of the group are complex and dynamic and change over time.6 The political pressure within the department can play a significant role when it comes to implementing a positive change, creating resistance to a change, or having a change fail. The political culture of the organization can have productive boundaries or unproductive boundaries; it is up to the leader or manager to decide what boundaries are being used within the organization. The fire service is made up of many different people; as a result, the organization is now faced with many differences among the group members, resulting in different, and at times conflicting, boundaries. A fire chief, union president, and fire association president all have political cultures to deal with when it comes to the individual groups of people; the goal of each leader is to have the group (department, union, association) focus on the positive boundaries that bring about positive results. If the leader can identify and respond to the different boundaries within the group, the leader stands a better chance at allowing the organization to adjust to the proposed change. Keep in mind that no one factor will determine how the organization will respond to a change process; rather, the process is often made up of dynamic factors, and what works today is no indicator that the same results will be achieved months or years later.

POLITICAL PRESSURE

The fire department is made up of culture and subcultures. At times, the cultures work together; at times they may not. Political pressure arises when a group of individuals with vested interests within the fire department or the community influences the behavior of the group, determining what the group will accept or reject. Individuals and the groups may have formal or even informal sources of power.7 For example, the Finance Committee may have formal power to recommend or not recommend a fire department budget item. On the other hand, a group of firefighters may not have any formal authority in creating and approving policy in the fire department, but the group may set the tone and behavior for the group’s response to a policy change. This political power (internally and externally) can make or break change in the fire department. Political pressure from these two cultures must be considered when proposing and implementing change.8 The leader or manager who uses too much positive or negative feedback risks damaging the proposed change. When too much praise is given, the focus is shifted from the change to the praise. The loss of focus can damage the change process within the political forces of the organization. On the other hand, too much negative feedback will send the message to the organization: Stop what you are doing and go back to the old way. Hence, the misuse of positive or negative praise can impact the change process within the culture of the fire department.

The fire department organization is made up of individuals with formal power and individuals with informal power. The formal power is based on rank—for example, the fire chief or the captain. The informal power may be a senior person in the department whom everyone in the organization looks up to and respects based on his experience. In some cases, the informal power can be as powerful as the formal power. The pulling and pushing of these formal and informal powers can alter or totally change the political landscape of a fire department. The words and behaviors of the formal or informal leader can exert a negative or a positive influence on others in the organization; this influence allows the group members to deliver the goals and objectives of the organization. The influence from formal and informal leaders often can determine how successful the proposed change will be.

In addition, the information/communication process used in the fire department can impact how change takes place. Fire service leaders who limit information/communication to other members of the group risk that the members will be frustrated by the lack of information and withdraw from the process. Prior damage to the communication process can have a long-standing impact on the organization and can take a great deal of time and energy to repair. The goal is to have the fire service leader connect to the formal and informal groups to determine ways that they can connect on some level. The connection may be very small at first, but growth can be achieved with open, honest, and respectful communication. Once a solid communication dialogue is created with formal and informal groups, action will often follow the words, creating a healing process among the members of the organization. (8) The information/communication process used in the fire service can be easily damaged and require extensive time to repair, but steps need to be taken to begin the process of reconnecting with the members of the organization.

The political process in the fire department can be seen as a twofold process (Figure 1). The first process is the “on stage” political process, the one used in front of people at public meetings. The second process is the “backstage” performance in which the individual uses political strategies and tactics that are not transparent to the general public. The individual will attempt to recruit a support group or maintain a reduction of resistance to the change.9 The backstage process may involve influencing, negotiating, and defeating opposition within the cultural system that surrounds the possible change. If you have spent any time in the fire service, chances are you have seen how political pressure is applied in positive and negative ways. The “on stage” and “backstage” behavior demonstrated by leaders/managers provides new members of the organization with the acceptable behavior of how things are accomplished (for better or worse).

| Figure 1. Negative Aspects of FD Politics |

|

The negative aspect of the fire department politics that can consume a department is people intimidating others into a central line of thinking and members of the department being discouraged to think for themselves or express ideas that are outside of the norm. The deception is used when the person or group wants to deceive the people to whom they are presenting the change. This might be considered a “trick” to get people to believe.

The other negative aspect is lying. For example, a firefighter has a one-on-one conversation with a commanding officer, and the commanding officer tells a totally different version of the conversation to others. During my tenure in the fire service, I have seen firsthand how some people and small groups have lied about certain things for personal gain.

The final area is backstabbing—when a very close ally betrays you. For example, the company officer has several firefighters he believes are close allies, and he finds out that one of those firefighters is talking negatively about him. Each of the aforementioned negative aspects of fire department politics can have a significant impact on the department and its culture. It is mission critical to assess and continue to monitor the fire department politics. Over a period of time, behavior patterns will emerge, and the leader/manager will need to determine what behaviors are important for the organization to meet its goals and objectives, support such behaviors and minimize, or attempt to eliminate over time, the unproductive behaviors of the group.

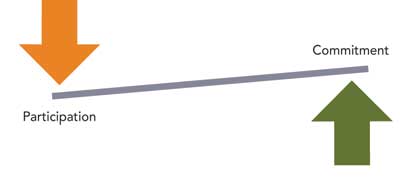

The goal of managing change is to gain the commitment of the individuals who will be impacted by the proposed change. Doing this will reduce the resistance to the proposed change and increase effectiveness. As you can see from Figure 2, commitment and participation have forces that can be used for acceptance of the proposed change. Hence, you may have a very high commitment level from the stakeholders; but, as a result of political forces within the department, you may have only minimal participation, resulting in unstable forces. As previously discussed, include those who will be impacted by the proposed change in the planning process (participation). Bringing the stakeholder into the process (participation) will lead to commitment. When commitment and participation are equal, the chance of successful implementation of the change increases. A change should have commitment and participation in equal forces; too much of one is unfavorable for the change process (Figure 2). How many departments have had a strong commitment from administration on a policy change, with little participation in the process? So, how did that policy change work out? Are members participating to the limit that they must? Within any fire service organization, the members can be influenced by political pressure and ethics that can determine if a change will succeed or fail.

| Figure 2. Change Management Forces |

|

Regarding political considerations within the department, the change manager should also consider past political successes and failures. The past must be respected. It often can help you to determine the negatives—anger, missteps, fads, and poor leadership practices—used in the past. The past culture of success or failure can live on within the organization and needs to be assessed when considering change. The old political wounds left behind from past failed attempts at implementing change are often left to fester; the infection will spread to the rest of the organization and affect the current change under consideration.10 Historical political pressure is often seen in the labor and management relationship when dealing with personnel issues. In the labor relations field, we tend to carry the past historical political pressure on our shoulders like a 10-ton block.

ETHICAL CONSIDERATIONS

As touched on before, the fire department politics, cultural, and ethical standing will affect the change-managing process. When individuals use power and political behavior to make decisions that will only serve their self-interest, it is considered unethical. In addition to ensuring that there will be no personal gain, the manager also needs to monitor the stakeholders involved in the change process to ensure that no unethical decisions are involved.

A leader who attempts to use or recommend a political strategy to implement a change that will not benefit the fire department’s goals, objects, or a larger group within the department is also considered unethical. Union leaders and the fire association president need to be aware of the political pressure and power they hold in the fire department culture. A president, for example, may use the power to sway the group to show the chief that he is a team player while he knows deep down that the real motive is to be rewarded with a promotion. Another example would be the union president or association president who purchases holiday turkeys at a local market. The president tells the market owner that the turkeys will be used as a fundraiser for local kids’ activities in the community. The market owner quotes a $1.00-per-pound price for the turkeys. The president tells the members the turkeys cost $1.20 per pound. The president personally pays the market for the turkeys and gets reimbursed by the association at the higher price. Because the president is not being truthful with the members and is using his position for personal gain, this action is unethical (and may be in violation of the association rules).

Another example of unethical behavior is the violation of people’s rights. Following are some recommendations for ethical and political behaviors within the fire department organization when implementing change:

- Refrain from “dirty politics.”

- Ensure that all benefactors for the change have been identified.

- Respect the resistance points.

- Research the historical significance of the change (heritage and tradition).

- Seek open/honest commitment and participation from stakeholders (network and honesty).

- Establish “ground rules” for managing the change process (may have to agree to disagree), due process. It is okay to make deals; you may have to make deals to gain support for the proposed change.

- The process must ensure fair treatment of all involved. Respect the environment (behaviors, values, and ideas).

When managing the change process, the leader must walk a fine line between influencing others to gain commitment and stumbling over the line into manipulation. The manager’s manipulating people to obtain commitment and participation is unethical. The goal should be to bring about change that is effective and ethical; if one of these elements is missing, it may be best to step back and reevaluate. The leader must know what he can and cannot control when dealing with humans. He must consider the politics, culture, and ethics as a system and know that he cannot totally control the system but can influence it by being an active participant.

Change management at various levels within the fire department involves political and ethical considerations. Keep in mind also that resistance to a change can be healthy. It is a reminder that we need to seek participation and commitment from those who will be impacted by the change. The resistance point provides a means for a balance between stability and change.11 The goal for the leader is to create an environment in which members can express their ideas and opinions; can have open, honest, and respectful communication across all organization boundaries; and the focus will be on the ideas and not on personalities. The leader of change must walk a fine line between being politically shrewd and exhibiting unethical behavior. The excitement, ego, speed of change, or the position could quickly cloud this fine line. Change management takes different shapes in an organization. Opening up the change process to a public process instead of deals being cut behind closed doors is the best approach to bringing positive change in an organization. Leaders who can understand and accept the organizational past will be better suited to creating a foundation on which they can build future changes.

References

1. Lambrechts, F., Martens, H., & Grieten, S. (2008). “Building High Quality Relationships During Organizational Change: Transcending Differences in a Generative Learning Process.” International Journal of Diversity in Organizations, Communities & Nations; 8(3), 93-102.

2. Miller, V.D., Johnson, J.D., & Grau, J. (1994). “Antecedents to willingness to participate in a planned organizational change.”Journal of Applied Communication Research; 22, 59-80.

3. Beer, M. & Eisenstat, R.A. (1996), “Developing an organization capable of implementing strategy and learning.” Human Relations; 49(5), 597-617.

4. Waldron, M. (2005). “Overcoming Barriers to Change in Management Accounting Systems.” Journal of American Academy of Business; Cambridge, 6(2), 244-249.

5. Gunningham, N., & Sinclair, D. (2009). “Organizational Trust and the Limits of Management-Based Regulation.” Law & Society Review; 43(4), 865-900. doi:10.1111/j.1540-5893.2009.00391.

6. Eoyang, G., (2009). Coping with Chaos: Seven simple tools. Circle Pines, MN: Lagumo.

7. Jackson, P.W. (1990), Life in Classrooms (New York: Teachers College Press).

8. John, S., (2009). Strategic learning and leading change. New York, NY: Routledge.

9. Coghlan, David, & Brannick, T. (2010). Doing action research in your own organization, 3rd ed. Los Angeles, CA: SAGE.

10. Deal, T., & Peterson, K.. (2009). Shaping School Culture, 2nd ed., San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

11. Macri, D., Tagliaventi, M. & Bertolotti, F. (2002), “A grounded theory for resistance to change in a small organization.” Journal of Organizational Change Management; 15(3), 292-311.

PAUL J. ANTONELLIS JR., MA, is a 20-plus-year veteran of the fire service and has held various positions including chief of department. He is a student in a Doctoral of Education program with a specialization in educational leadership and management. He has a master’s degree in labor and policy studies, with a concentration in human resource management. He has lectured to emergency service providers nationally and internationally. Antonellis has authored and had published many articles and three books. His most recent book is Labor Relations for the Fire Service (PennWell Publishing, 2012). He is on the faculty of four colleges, where he teaches at the undergraduate and graduate levels and is responsible for curriculum development. He has presented at FDIC for several years.

Fire Engineering Archives