It’s 3 a.m., and I am riding Rescue 1 on an overtime shift. Dispatch toned the initial alarm out to respond to a working fire that the police officer called in. Unknowingly, that same officer assisted in the fire’s growth by opening the front door to see if the structure’s homeowners were inside, thus giving the fire fresh air.

Our unit split into two companies, one group on each division, and made the first-in search. The driver and I searched all rooms on division 1 and completed our search with good visibility. As we approached the stairs to get to division 2, we watched the fire roll upstairs into the attic space—frankly, we were a little envious of the members upstairs doing solid work for the public we serve.

After the first five minutes, we fast-forwarded to a hot bottle swap from a slightly used first bottle as we were pulled to another task. One refill later, we were starting to feel fatigued and ready for a little rehab. We took that moment as we sat in an upstairs bedroom with an on-site finishing overhaul and cleaning up hot spots with another crew assisting.

As I looked at the third man on the rescue, probably one of the most fit individuals in our department, I thought, “Thank goodness for my developed biofeedback skills.” I’m in good shape myself, but there is always room for improvement. Age, among other factors, will always play a role in our air consumption rate (ACR). I am, however, prepared.

I don’t just practice my craft through continuous training; I regularly practice one of the most important functions needed to do my job effectively: air management. If the circumstances allow, you will see me in my gear daily. I’m on air working, training in gear at least three or four times a week to have continued practice breathing under duress. I have my own self-contained breathing apparatus (SCBA) for this purpose. I’m all in, but I wasn’t always that way. Little did I know something called “biofeedback” would be the start of a rekindled passion in my career—a tool that would give me the ability to manage and extend my air when it counts.

Mysterious Ailment

When you feel your career may be gone in the blink of an eye, things get put into perspective. At 28 years old, married fewer than six months, and with a baby boy to take care of, I would encounter this feeling. This is the short version of a very long story that led me to finding biofeedback.

In the beginning of 2013, I went from running three to five miles a day to struggling to climb a flight of stairs in a matter of weeks. On standing, my heart would race, and I would get palpitations out of nowhere. Other prominent symptoms included dizziness, erratic breathing, and weakness. The emergency room (ER) doctors said it was anxiety. I said “nope.” I was losing weight, strength, and endurance at an unsettling pace. My symptoms became unmanageable, putting me and others at risk. Still not knowing the root cause, I had to make the painful, but smart decision, to go to my captain and ask to take a leave of absence, length of time unknown. Little did I know then that I would be off the rig for the better part of a year. There were repeated trips to the ER, hospital stays, numerous doctors, misdiagnoses from every so-called specialist, and still no answers.

My “Web MD” wife was my rock and my strength in this time of weakness. Through her continuous research, she found a doctor who specialized in a syndrome that matched all my symptoms. After two months of testing, I was diagnosed with postural orthostatic tachycardic syndrome (POTS), in which changing your body posture from lying to standing causes an abnormally large increase in heart rate. There can be many known and unknown causes of this condition. In my case, it was linked to adrenal fatigue and oversecreting adrenal glands with an oversecretion of norepinephrine and a possible viral infection. It may go away, or you may deal with the symptoms on and off through your lifetime.

The main treatment is cardiac rehab. I worked out six days a week in pools, on rowers, and on low weight resistance machines. The goal was to increase heart muscle and stamina. In this condition, essentially, your heart atrophies and shrinks, which is why it is called the Grinch syndrome.

Many of the medications used to treat this are aimed at keeping your heart rate and blood pressure low. I refused any medication because I was afraid that the doctors would not try to help eliminate the disease if they could just manage my condition with medications. I wasn’t going to let it define me. The next step was to create a treatment plan to recover all that I had lost and to get back to work. We knew I was working against the odds, but that didn’t stop us from finding the treatment that worked (without medication).

Discovering Biofeedback

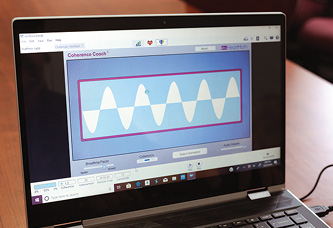

Enter the world of biofeedback. My brother, a physician, came across biofeedback during my illness. I was very skeptical, but that quickly diminished when I found that biofeedback was teaching me how to manage my major symptoms (dizziness, erratic breathing, increased heart rate, and heart palpitations), which had once felt out of control. I started learning how to use this technique in a doctor’s office with the aid of a program, kind of like a game.

Now, when I practice it in my daily life at home, at training sessions at the station or gym, or during moderate cardio exercise, I use a device that fits in my pocket (photo 1). It monitors my heart rate variability; my respirations; and my coherence, which is the quality and form of my set breathing patterns that I applied. The breathing patterns are as follows: Inhale for 4 seconds; hold for 2 seconds; exhale for 4 seconds. As I get better and more proficient, I am able to increase the separation so I can inhale 6 seconds, hold for 2; exhale 6 seconds, hold for 2. Effectively, this is breathing 3 to 4 times a minute and activates your parasympathetic nervous system.

(1) Photos by Carlie Jean Photography.

It keeps me relaxed (a plus), but with this repetition I can easily get into a state of calm and controlled breathing in any situation that I have faced since I was hospitalized. In some situations, it takes longer than others to get into coherence. It is a practiced skill and is easily accessible when I need to influence (the key word) those aspects of my involuntary system, such as heart rate and blood pressure, which, in effect, help ease my respirations even more.

On the physical side of my recovery, cardiac rehab means lots of rowing, pool exercise, and swimming. I spent most days doing cardio in a pool to allow my heart to work without the weight of gravity to create lean muscle growth. The objective was to help recover endurance and blood flow. My heart had literally shrunk during my illness, and it was time to build it back up. Six years later, biofeedback is something I still use in my daily life and, most prominently, in my work life. It saved my life, and it could save yours.

What Is Biofeedback?

Biofeedback is a mind-body technique in which individuals learn how to modify their physiology to improve physical, mental, and emotional health. Much like physical therapy, biofeedback training requires participation and regular practice between training sessions. It can improve emotional and physical states, such as anxiety, depression, and other symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD); it has additional cognitive benefits as well. It has been shown to reduce performance anxiety, cognitive decline, and mental noise. Stress-related cognitive decline is thought to result from the effects of prolonged elevations of cortisol. Cognitive dysfunction is also a main symptom of POTS patients. Its symptoms include brain fog, poor memory, and the loss of fine motor skills during stress. I have found that by forcing myself to breath more slowly, I reduce my cognitive decline by keeping my brain and memory focused on the task at hand.

Mental noise is the constant chatter of the brain that never stops; it gets louder when your stress levels are up and can force some to make a mistake because they don’t slow down to think. With practice, the performer can self-generate and sustain high-performance states.

Biofeedback takes practice to master and works best when you can get a physician or a program to help with guided instruction, as I did. In biofeedback, you use breathing techniques and a focused mind to help control or influence involuntary body functions such as your heart rate, skin temperature, and blood pressure and mitigate cognitive decline.

With a few exceptions, every firefighter has tried this, if only for a few seconds knowingly or not. Have you ever tried to slow your rapid air usage to give a calm radio report without SCBA interference? In this age of safety and rehab, have you been asked to stop and do a blood pressure check? What do you do? You can tell those who use breathing techniques consistently and those who are using them only at that moment. They go from talking and cutting up to looking like my son when he gets caught trying to watch TV after bedtime. We all know that look, and they just have to hit the noninvasive blood pressure button to retake their blood pressure again and again until the number looks pretty.

What if we didn’t need to do that? What if we were educated, instructed, and trained to perform breathing skills as often as we pull hose or throw ladders, lift weights, and run? Physical conditioning is probably the single most important thing we can do to prepare to help the public we serve when seconds count. I’m not saying, “Learn to breathe, and everything else will work itself out.” However, the SCBA comes with a fixed capacity to which it can be filled, and we can extend the time of its use with the proper techniques. Our lungs and brain are tools that can be trained, sharpened, controlled, channeled, and improved. It is up to each firefighter to step up and each company officer to know the working capacity of all tools and resources on their rig. This includes the personal capacity and abilities—mental, physical, and physiological—of their fellow firefighters.

Breathing Techniques Resources

Two books assisted me in my journey to educate myself on overall firefighting breathing techniques—Air Management for the Fire Service and Developing Firefighter Resiliency. Each offers effective strategies for incorporating breathing and focus techniques, as well as classes based on these principles. The technique has been successful for me but isn’t well-known within the fire industry. Biofeedback and other well-known SCBA breathing techniques help close the gap to master this very important aspect of our work.

Over the past six years, my training has evolved from my experience with biofeedback. Part of it is using a method that changes with the physical exertion capacity at which I’m functioning. It is less about the rate and more about the coherence for me at higher exertion levels.

Coherence

Coherence refers to the physiological coherence resulting from the practice of sustaining positive emotions and breathing. Biofeedback can teach us how to better synchronize the parasympathetic and sympathetic nervous systems, the two branches of our autonomic nervous system. Also, when we talk of our coherence, it is in conjunction with our heart rate variability (HRV), which is the measure of the naturally occurring beat-to-beat changes in heart rate. Through my biofeedback practice and repetition, I have gained the ability to reach a state of positive coherence quickly.

When I practice without the SCBA and under normal conditions, I tend to stick to an 8-2-8 repeat, which is a form of box breathing. I do this while imagining a structured flow, such as that of a capnography wave form, from an end tidal CO2. Inhale for 8 seconds, hold for 2 seconds at the top, exhale for 8 seconds, hold for 2 seconds at the end of the exhalation, and repeat. At this rate, I breathe approximately three to four times a minute. As I get more comfortable during my practice, I lengthen the duration of inhalation and exhalation during multiple modes of exertion. Practicing this daily allows me to easily, quickly, and effectively influence my respirations and physiological response. This helps to prepare me for any exertional workload I’m under within any environment.

Biofeedback in the Fire Service

Although many athletes, military, and medical professionals have used biofeedback, introducing it into the fire service may be a challenge. It’s one that I am passionate about because I know it works. This tool can help the average person in so many ways, but first responders aren’t allowed to be average. Just research the effects of the unstable nature of firefighting work—e.g., shift work disorder, adrenal fatigue, and so on. Let’s do what we can to improve our odds.

Implementation would look something like this: As a crew, you would do individual drills using a device called an “emwave” that your peers would monitor. The emwave device helps you understand the correlation of responses between your heart and your brain. It is a tool for finding your coherence in any situation. The goal is to learn how to sustain positive coherence without using the device. Your crew would practice breathing control in the morning during stretching, on the elliptical bike or rower, and at night before they go to bed. Doing this helps stabilize your chemical response throughout the day.

Next, your crew would take turns using the biofeedback software while breathing on SCBA on a treadmill with minimal exertion (photo 2). Then they would do moderate exertion with a consumption drill until the vibration alert activates, all the while maintaining positive coherence levels. They can then take it to the next level, using it in conjunction with wheel breathing. The objective is to add biofeedback to your tool belt along with other proven effective training. Introducing this method into your training will make it part of your muscle memory at rest times and at different exertion periods.

(2) Photos by Carlie Jean Photography.

SCBA ACR

Let’s consider your SCBA’s average ACR. It’s an average, but it’s based on math that doesn’t accurately account for the working capacity of a firefighter.

Picture your crew performing biofeedback with ease and extending their time safely in a structure. Your officer assigns a task that has a high exertional output. He is comfortable with that because he knows everyone’s physical ability and their capacities to function, too. He can now also extend the time in a structure by splitting workloads to get the most out of the crews’ ACRs. He will know which crew members’ vibration alerts will activate during training or who the crew’s “air hog” is. With a shared workload, we can accomplish most of the work to “air used ratio” when needed because of the crew’s understanding, practice, and repetition of biofeedback and their ACR.

Biofeedback with positive coherence at a moment’s notice with a few breaths would give a crew member who has performed heavier exertion the ability to decrease his cognitive decline. By lowering respirations and pounds per square inch usage, the member can stay in the structure to assist the crew with the remaining workload (photo 3).

(3) Photos by Carlie Jean Photography.

In addition to departmental training, some biofeedback techniques are already integrated into training within the fire service. Each year, top-notch classes are offered through the Georgia Smoke Divers (www.georgiasmokediver.com), Saving Our Own classes, and firefighter survival courses, among others. Some of the best in our field are out there teaching proven life-saving techniques to take back to your departments.

So, let’s take it up a rung. What if we had firefighters who were already using biofeedback train with these groups under stressful situations and then come back to continue the training as a part of their regimen? Adding these skills to their routine while using biofeedback would increase their muscle memory to function at even higher exertion levels, giving them an enhanced version of the training they have received. It not only benefits that individual but also the crew he rides out with and the public they serve.

Biofeedback was a last-ditch effort to improve my physiological responses during a time of unexpected duress. I just wanted to get better. I didn’t realize that it could positively affect my everyday life inside and outside of the fire service. Experiencing the difference it has made in my training and life in general is reason enough for me to spread the word.

Multiple biofeedback training aids and programs are available to assist in practicing this technique; physicians guide the training. Most will train using interactive feedback on the computer. I used emwave; I received the device during my recovery, but other options are available. Do your own research.

Obtain some guided lessons for the station or yourself. If you oversee an aspect of your department’s budget, see if you can set up lessons from a doctor who specializes in this field. Until the department of health and safety division invests in a guided program like this, we must implement biofeedback techniques on our own. We work on the physical aspects of our skills to become stronger, faster, and more high functioning. Let’s do the same for our mental and emotional capacity. In the end, our life may depend on it.

Endnotes

Carpenter, Bob; Gillespie, David; Jorge, Ric. (2019) Developing Firefighter Resiliency. Fire Engineering Books & Videos. https://fireengineeringbooks.com.

Gagliano, Mike; Jose, Phillip; Phillips, Casey; Bernocco, Steve. (2008) Air Management in the Fire Service. Fire Engineering Books & Videos. https://fireengineeringbooks.com.

Marino, Dominick. (October 2006) “Air Management: Know Your Air-Consumption Rate.” Fire Engineering.

McCraty, Rollin, Ph.D. (2002) “Heart Rhythm Coherence—an Emerging Area of Biofeedback.” Heartmath Institute. https://bit.ly/2Bzqi5e.

Rollin McCraty; Dana Tomasino, B.A. (2015) “Heart Rhythm Coherence Feedback: A New Tool for Stress Reduction, Rehabilitation and Performance Enhancement.” Heartmath Institute. https://bit.ly/31zSHD9.

MATTHEW SAPP is a firefighter/paramedic with the Frisco (TX) Fire Department assigned to Station 1. He has completed the Texas A&M TEEX Rescue Specialist program and is a rescue specialist for Texas Task Force 2 (TX-TF2).