FEATURES

FIRE REPORT

Photos by Elmer F Chapman

HIGH-RISE: An Analysis

The nation’s most destructive high-rise fire begins to reveal some of its lessons.

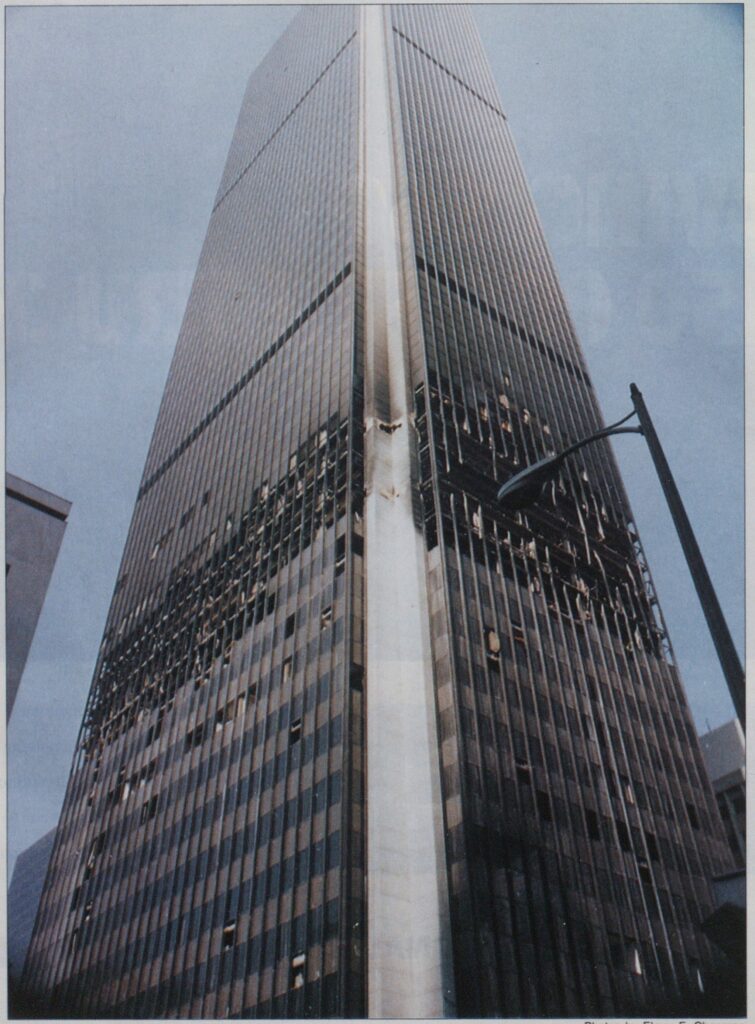

On May 4, 1988, at about 10:30 p.m., fire broke out in Los Angeles’ 62-story 1st Interstate Bank building. In terms of damage and severity, it was the most devastating high-rise fire in United States history.

The fire destroyed five floors of the structure. Four of the floors sustained complete devastation of the occupied space for the full 360 degrees around the center core. It’s estimated that damage from fire, water, and smoke will incur $400 million dollars in restoration costs.

Fifty-eight fire department units and more than 275 firefighters were used to fight the 1st Interstate Bank fire. This represented 40 percent of Los Angeles City Fire Department’s on-duty personnel. It took approximately three-andone-half hours to extinguish the blaze.

There were more than 40 people in the building at the time of the fire. Some were bank employees working late in their offices; others were security, cleaning, and maintenance personnel. Ironically, there was also a crew installing a sprinkler system in the building. Some of these people escaped by use of elevators and stairways. Some of those who attempted to use the elevators became trapped and narrowly escaped with their lives. After the fire, three elevator cars were found in the fire area where they had been taken by building personnel using special keys. Other occupants were trapped above the blaze, where they remained throughout the fire, some for as long as five hours. About 8 persons were removed from the roof by police and fire department helicopters. One person was killed when the elevator he was using stopped at the fire floor and opened its doors. Twenty building occupants and three firefighters were injured. All injuries were minor.

The building

The 1st Interstate Bank building, located at 707 Wilshire Boulevard, at the corner of Hope Street in the downtown L.A. business district, is 858 feet tall, making it the tallest building in California and the 18th tallest in the United States. It’s 63% occupied by 1st Interstate Bank as its corporate headquarters. They employ about 2,500 people. The remainder of the building is leased to 30 other occupants, including foreign banks and legal firms. The total daytime occupancy of the building is about 3,500. The building is owned in partnership by 1st Interstate Bank and Equitable Life Assurance Society of the United States.

The building was first occupied in October 1973. It was, at that time, the tallest building west of the Mississippi, known as United California Bank Tower. The building codes then in effect did not require that a sprinkler system be installed. In 1974, the building code of the City of Los Angeles was amended, requiring that all future high-rise buildings be equipped with an automatic sprinkler system, but this requirement was not made retroactive.

The building’s dimensions are approximately 120 feet by 180 feet, with a gross area of over 21,000 square feet per floor. The core of the building occupies an area of 4,000 square feet per floor, leaving 17,000 square feet of tenant space on each floor. The floor areas on all 62 stories are the same. The building has no setbacks.

The building is of lightweight, fire-resistive construction. The floors are “Q” decking supporting reinforced, low-density concrete. The steel framing and the underside of the “Q” decking is protected with sprayed-on fire retarding of cementitious material. The quality of workmanship in the application of this material was unusually good and it was very effective in protecting the primary structural members. As a result, very little damage was done to the primary structural members of the building despite the long duration and high temperatures of the fire.

The outside wall is glass set in aluminum mullions. The failure of the glass and the aluminum mullions was a major factor in the vertical spread of the fire. Also, the lack of firestopping between the floor slabs and the skin permitted the fire to spread from floor to floor through this space. Fire was observed spreading through this area even before the glass and mullions failed.

The fire stairs were equipped with fire doors that were rated for 1½ hours. They consisted of an outside covering of wood veneer over an interior of gypsum that had no structural strength. When the wood veneer was consumed by the fire, the door lacked structural strength. It remained in place as long as the door was in the door frame, but when opened, the door collapsed.

The fire

The first alarm was received from a smoke detector on the 12th floor at 10:30 p.m. This alarm was located in the southeast corner of the building near a bank of computers. This area was a computer nerve center with more than 130 trading stations, each equipped with a computer terminal, a monitor, and a bank of telephones. Two minutes after the first alarm was received, three more alarms activated. Two minutes after that, four more alarms were received, including some that had been reset.

Five minutes after the first detector was received, a radio message was transmitted to a maintenance engineer to investigate the cause of the alarms. At 10:36, multiple alarms were received for smoke on the 13th through the 30th floors. At 10:37, 911 received the first of three calls from neighboring buildings reporting a major fire in the 1st Interstate building.

The Los Angeles City Fire Department dispatched units that arrived at the scene at 10:40 p.m. The fire was then showing on the south side at the 12th floor level. The fire was observed from the quarters of Task Force 4, located over one-and-a-half miles away, at the time of the receipt of the first alarm.

Shortly after the arrival of the first units, the fire extended to the east side of the building and to the 13th floor. The fire was fed by a heavy fire loading on the 12th floor, a vast array of computer and communications equipment. The fire extended upward by auto-exposure through glass window and aluminum mullion failure and through the nonfirestopped opening between the floor slab and the skin. The vertical spread was also through poke-throughs, pipe recesses, and utility shafts.

One of the major avenues for the vertical spread of fire, heat, and large volumes of smoke to the upper floors was the return air shaft (RAS) for the heating, ventilating, and air conditioning (HVAC) system. The RAS for the HVAC system ran uninterrupted from the 12th floor to the 32nd floor, with the mechanical equipment room on the 22nd floor. The RAS was not located within the core, but rather, adjacent to it in the occupied areas, and terminated on the 12th floor, about three feet below the ceiling. Just enough of the RAS was located on the 12th floor to install the return damper in the shaft.

The RAS was constructed of ⅝-inch plasterboard on metal studs. When this was exposed to the fire on the 12th floor, the bottom of the shaft fell out, allowing the fire to extend to the 13th and 14th floors when the shaft walls failed. The smoke and heat extended up the shaft, and the smoke entered all floors via the return air dampers, actuated not by smoke, but by heat. The heat failed to close the dampers because the fusible links were located on the floor side of the dampers. The fire did extend from the shaft enclosure on the 27th floor, where a fault in the enclosure existed. This fire was in a storage room and did not promulgate.

The fire spread upward from the 12th to the 13th, 14th, and 15th floors, and was finally stopped on the 16th floor. The reasons for the stop of fire on that floor were :

- a decrease in the fire loading on the 16th floor;

- the increase in compartmentalization on the 16th floor (the fire spread mostly to small compartments, where manual fire suppression was more effective);

- fuel on the lower floors was being exhausted;

- lines moving in and darkening down the fire on the floors below; and

- the selection of this floor by the chiefs in charge to make a stand. (The mustering of forces on this floor to carry out strategy and the aggressive attack by the firefighters permitted them to maintain possession of this floor and stop further vertical spread of the fire.)

The fatality

At about 10:30 on the evening of the fire, elevator freight car 33 was being used to remove trash from the upper floors at the 1st Interstate Bank building. Alexander Handy, a maintenance engineer, was preparing to go home at the end of his shift when he was notified that a smoke detector had activated on the 12th floor. Handy boarded car 33 with its load of trash still aboard; using a special key, he activated the car and proceeded to the 12th floor. When he arrived at the 12th floor he pushed the “door open” button. The doors opened and he was immediately engulfed by intense heat. The freight elevator opened onto an enclosed freight elevator lobby on the 12th floor, but the door to the lobby had been blocked open. Handy was heard on the handietalkie radio frequency to call out, “Help, help! Car 33 is in flames!”

There were no other radio transmissions from freight car 33. His body was found at about 4:00 a.m., two hours after the fire was extinguished. He was buried under the trash in the car. The special key was melted in the key slot in the “on” position, and the car doors had melted half away. The location of the freight elevator lobby on the fire floor was almost at the opposite end of the floor from the location where the fire was believed to have started.

Water supply

The building was equipped with a standpipe system, with hose outlet valves located in the stairways and hose cabinets located in the occupied areas on each floor. The standpipe was supplied by fire department connections located on the north side of the building, one on each end.

The standpipe system was also supplied by two 750-gpm fire pumps located in the below-ground area of the building. One pump was driven by an electric motor; the other was driven by a diesel engine. These fire pumps were supplied by an 85,000-gallon suction tank. This tank was supplied in turn by water main connections and could be augmented through fire department connections.

At the time of fire, there was a crew of workers installing a sprinkler system in the building. The $3.5 million sprinkler system was 90% completed, but not operational. It was due to be completed in July. The sprinkler system on the floors destroyed by the fire were completed but not supplied with water.

Prior to the fire, the building maintenance engineer shut down the fire pumps and partially drained the standpipe system to permit the sprinkler installers to make connections. After doing so, he moved to an upper floor, where he was trapped when the fire broke out. He couldn’t get down through the building, so he went to the roof and was rescued by a police helicopter.

The police helicopter flew him to their helo pad at Temple Street and Grand Avenue. He was needed at the fire scene to restore the fire pumps, and police drove him to the incident command post, located across the street from the fire building. Since falling glass and burning debris made it extremely hazardous to enter the building, he was ushered into a fire department car and driven via tunnel to the building’s underground parking garage. (The building’s system of driveways and underground parking garages provided a vital means of access to the building.) The engineer restored the fire pumps to full operating condition and even got the diesel backup pumps on line.

The restoration of the fire pumps corrected a serious problem that was hampering effective line advancement: lack of water pressure in the standpipe system. An estimated 40 minutes elapsed before adequate pressure was supplied to the standpipe system. Hoselines stretched into the fire department connections on the exterior of the building were severed by the falling debris and glass shards. Replacing the lines was very dangerous because of these conditions. In fact, a car parked on the street in front of the fire was set ablaze by the falling debris.

The fire was so intense that it caused aluminum hose outlet valves in auxiliary hose cabinets located within the tenant occupancies to melt. This caused additional lV$-inch openings in the standpipe supply with resultant pressure loss. Water from these pipes discharged ineffectively onto the fire floors.

Disaster plan

The previous most disastrous high-rise fire experienced by the city of Los Angeles was the fire in the 32-story Occidental Center Towers on November 19, 1976. This fire caused $3.6 million of damage. The building was completely renovated after this fire, but the owners did not see the need to install a sprinkler system in this building, nor did the City of Los Angeles see the need to require a sprinkler system in all high-rise buildings at this time.

After a fire at the Northwestern National Bank in Minneapolis, on Thanksgiving Day 1982 (which caused that bank to suffer a $50 million business interruption loss), 1st Interstate Bank started to put together a disaster plan to protect itself. This $1.5 million plan was completed about a year-and-a-half ago and had been practiced less than a month before the fire. Less than an hour after the fire started, this plan was initiated and 1st Interstate started to organize its key managers to keep the fire from interrupting the normal business of the bank.

This plan was so successful that on the day after the fire, the bank showed a profit in the stock transactions that were conducted by the security traders whose offices had been located on the 12th floor.

See “Lessons Learned,” page 60.