By Dan Kerrigan and Jim Moss

“You don’t have to get ready if you stay ready.”-Jake Lovejoy

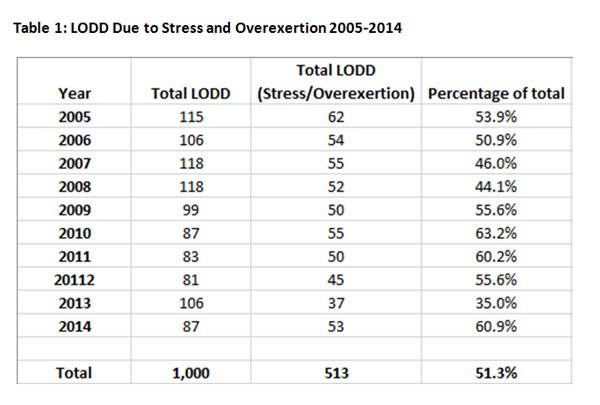

According to the United States Fire Administration, 1,000 firefighter line-of-duty deaths (LODDs) have occurred in the United States between 2005 and 2014. Of those, “stress and overexertion” (defined by the United States Fire Administration (USFA) as cardiac, cerebrovascular, and climatic thermal exposure in nature) were blamed for 513 or 51.3% of these deaths (See table 1). This statistic is alarming and illustrates the dire need for us as firefighters to place primary focus on improving our personal physical fitness.

The fire service needs to be passionate about firefighter fitness:

1. Being fit for duty is the most basic requirement for every firefighter–both career and volunteer.

2. Improving personal fitness will play a large role in reducing the number of LODDs that the fire service suffers each year, specifically those caused by medical and cardiac issues.

The question remains: What is the best way to improve our fitness as firefighters? Some experts emphasize the importance of improving our cardiovascular capacity. On the other end of the spectrum, some firefighters may only choose to lift weights, neglecting other important aspects of their fitness. A holistic approach to improving our fitness, specifically a functional fitness approach, is the best solution. You may have heard the term “functional fitness” before, but what does it means to be a firefighter who is functionally fit? Functional fitness is a method of fitness that uses real-life activities and positions to best prepare you for optimal fireground performance. In other words, fitness training must directly reflect of the level of dynamic fitness required for the fireground.

Disclaimer: We are not licensed physical trainers, nutritionists, or dietitians. What is expressed in this article are fitness components and an overall approach that have helped us achieve and maintain functional fitness throughout our careers as firefighters.

The Big Eight

Within the realm of firefighting, thinking about functional fitness training in terms of “the Big Eight” will help you improve your ability to execute basic fireground tasks, reduce the occurrence of injury, increase resiliency, and improve the recovery process.

“The Big Eight” consists of five functional movements and three interrelated fitness components:

1. Push

2. Pull

3. Carry

4. Lift

5. Drag

6. Core

7. Capacity

8. Flexibility

“The Big Eight” encompasses three general fitness fundamentals: flexibility/core strength, cardiovascular capacity, and strength training. By adding the fourth fundamental, nutrition and lifestyle, you can begin to develop a roadmap to optimal firefighter functional fitness. Functional fitness has many options and approaches, but it is the best solution to help you be fit for duty and enjoy a long career in the fire service.

Flexibility and Core Strength

Flexibility and core strength are often the most neglected areas of firefighter fitness. However, improving these elements has been shown to decrease the frequency and severity of sprains and strains, according to a research study performed by Matthew T. Anderson (2002). Think about it, when you are working on the fireground, not only do you exert yourself beyond normal limits, you are also maneuvering your body and working in some of the most awkward positions imaginable.

In firefighting, proper body orientation to the task at hand is not always possible. Since you do not have the luxury of proper technique all the time, you must ensure that your body is flexible and that you maintain a strong core. This will help reduce the frequency of fireground injuries.

There are many approaches to obtaining a strong core and increasing flexibility. From a holistic standpoint, yoga is a very effective medium for improving both flexibility and core strength. Some firefighters may roll their eyes and scoff at the idea of doing yoga because they believe it is not challenging or applicable to their fitness. After participating in yoga for the first time, however, most will admit that it is quite the workout. Yoga has been shown to increase muscular endurance, reduce muscular fatigue, increase flexibility, reduce stress levels, and improve core strength.

Check out these instructional video clips for yoga:

For alternative exercises that help improve our core strength, consider the following:

• Hanging leg raises

• Prone leg raises

• Russian kettlebell Turkish getups

• Russian kettlebell Swings

• Leg lifts

• Planks

• Variations on the sit-up

Also, consider these additional stretches for improving our flexibility:

• Windmill stretches

• Frog stretches

• Hip flexor stretches

• Weighted squat holds

When addressing core strength and flexibility, the beauty of these movements is that they can be done in conjunction with your regularly programmed workout of the day, or as a standalone workout.

Here are some short video clips for core strengthening:

Cardiovascular Capacity

When engaging in strenuous fireground activities, firefighters frequently meet or exceed their theoretical maximum heart rate. Even the fittest firefighters experience extreme strain on their bodies while on the fireground. Stretching attack lines, carrying heavy equipment, performing ventilation, forcible entry, rescuing a victim–all of these activities elevate the heart rate and require a tremendous level of cardiovascular fitness.

Improving cardiovascular capacity off the fireground will help your heart, lungs, and body perform longer and harder when you are in the heat of battle, and it will also help you to make better decisions while on the fireground. As Dr. Richard Gasaway has shared in his Situational Awareness Matters program, an increase in heart rate will start to affect decision-making abilities for the worse. When you improve your cardiovascular capacity through regular exercise, you train your body to maintain a lower heart rate and recover faster when performing fireground activities.

There are two primary ways to improve cardiovascular capacity: 1) High-intensity interval training and 2) endurance-based cardiovascular training.

High-intensity interval training (HIIT) combines alternating periods of intense anaerobic exercise with less intense recovery periods. HIIT is very similar to fireground activities: perform a high-intensity action (i.e. stretching/advancing an attack line) balanced with lighter to moderate activity (i.e. flowing water from the attack line).

Incorporating HIIT into your workouts is simple. If on the treadmill, run at a faster speed (e.g. near sprint) for two minutes and then slow down to a moderate speed (fast walk/light jog) for the same amount of time or less. The goal is to increase work capacity, endurance, resilience, and recovery in a manner that supports fireground functions (relatively short bursts of high intensity, strength-reliant work). To do this, rapidly elevate your heart rate for a brief period of time and then let it recover for a brief period of time. Repeat these cycles for a total of 20-40 minutes. In addition, kettlebell complexes, sledge hammer forcible entry simulations, sprints, front squats, and stair climber sessions are all also suitable HIIT exercises.

Endurance-based cardiovascular training is very simple: Perform medium intensity physical activity that elevates and maintains your heart rate to 70 percent of your maximum heart rate. For example, this could be running at a speed of 6-7 MPH for a total of 30 minutes. Alternatives would be 30 minutes of the following: Swimming, biking, rowing, elliptical trainer, etc. To calculate your maximum heart rate, use this formula: 220 BPM – Age = Maximum Heart Rate

Check out this crawl and drag exercise that improves cardiovascular capacity and flexibility:

Strength Training

Strength training is the third fundamental component to functional fitness. Firefighters tend to traditionally equated strength training to “lifting weights.” However, your functional strength should directly relate to your ability to carry, lift, drag, push, and pull.

We performed a simple experiment that aimed to quantify the amount of weight that a firefighter carries when dressed-out in full turnout gear. The results are as follows:

• Firefighter’s base weight: 200 pounds

• With full gear, helmet, mask, and SCBA: +69 pounds

• With a set of irons: +25 pounds

• With a water can/extinguisher: +30 pounds

Therefore, a firefighter in full personal protective equipment with a set of irons and the water can add 124 pounds to their base weight, and that’s just carrying stuff. These numbers may seem alarming, but they are a realistic indication of the physical strength required of a firefighter.

Consider the strength-related tasks that are performed on arrival at the fireground:

• Hoseline operation

• Hooking ceilings and walls

• Carrying and raising ladders

• Carrying and dragging victims or fellow firefighters

• Hauling equipment up and down stairs

• Using heavy power tools

There are various other ways that we can build strength and therefore improve functional fitness. While it is critical to lift heavy things in order to get stronger; it’s also important to focus on the areas of the body (muscle groups) that demand the most out of us, such as the legs, shoulders, triceps, lats, and grip strength.

Exercises that improve these functional areas include:

• Front Squats

• Back squats

• Loaded carries (especially up and down elevations and with asymmetrical weight distribution)

• Overhead presses

• Hose pulls

• Battle ropes

• Pull-ups

• Push-ups

• Rows

• Lunges

• Barbell deadlifts

• Bench Press

Here’s a quick video of a few basic kettlebell movements that improve functional fitness:

Perhaps one of the most practical methods of improving functional fitness is by putting on turnout gear and SCBA and executing the same tasks that you perform on the fireground. Instead of “hitting the gym,” head to the training ground to master the basics: carrying, throwing, and climbing ladders; forcible entry; stretching and advancing attack lines; search and rescue; rapid intervention crew drills; and so on. Combine these tasks into circuit-style training for a good workout that also builds muscle memory and tactical proficiency.

Here are some video clips of functional movements in full turnout gear and SCBA:

Nutrition and Lifestyle

Think of your overall fitness like an iceberg: 30 percent of its visible mass is above the water–this would include exercise/physical activity. The other 70 percent of the iceberg’s mass is below the water (unseen). The latter is representative of your nutrition, medical conditions, and behavioral/mental health. It is these “unseen” areas that will have the greatest long-term impact on your overall fitness, especially if you are aiming to lose weight and keep your blood pressure and cholesterol under control.

If we are truly going to reduce the number of firefighter LODDs, it has to start in the kitchen. We often say of training, “You only get out of it what you are willing to put in.” The same analogy can be applied to nutrition: If you put in “pizza and ice cream effort,” you only will get “pizza and ice cream results.”

You can work out all you want, but if you only eat cheeseburgers, fries, and junk food, you are still putting yourself at an elevated risk for high cholesterol, hypertension, and coronary artery disease. As mentioned before, these are the predominant killers of firefighters.

You will be better off if you improve your diet and pay attention to your mental acuity and overall stress level. Strive for balance in your nutrition and a balance in your life–“everything in moderation,” we like to say. Balance an intake of healthy fats, proteins, and carbohydrates with plenty of fresh fruits and vegetables.

Additionally, take some time away from the job every once in a while to focus on family, friends, and other recreational interests. Doing so will lower stress levels, improve quality of life, and subsequently improve job satisfaction and performance.

Train Like We Fight, Fight Like We Train

The very foundation of fitness is movement. So the first step is to get off the couch, get moving, and encourage those around you to do the same. Once you are motivated to do this, you can focus on what will help you perform the job at your maximum capacity. Taking a functional approach to fitness will benefit you the most in what you do on the fireground.

To achieve optimal functional fitness, strike a balance between flexibility/core strength, cardiovascular capacity, strength training, and nutrition/lifestyle. Neglecting any one area will keep you from reaching your full potential and may adversely impact everyone’s fireground safety and performance.

We must train like we fight, and fight like we train. Lead by example and apply positive peer pressure to those around you, emphasizing just how important it is to take care of yourself. At the end of the day, your exercise regimens and lifestyle choices must reflect the fact that so many lives are affected by your personal level of fitness: your citizens, fellow firefighters, and most importantly, your family.

References

Anderson, M. T. (2002). The reduction/prevention of muscle and tendon sprains, strains, and overexertion injuries through pre-work stretching and flexibility training at Polaris Industries, Inc. Osceola facility. Retrieved from http://www2.uwstout.edu/content/lib/thesis/2002/2002andersonma.pdf

Smith, D. L., Liebig, J. P., Steward, N. M., & Fehling, P. C. (2010). Sudden cardiac events in the fire service: Understanding the cause and mitigating the risk. Retrieved from http://emberly.fireengineering.com/content/dam/fe/downloads/2014/08/Sudden-Cardiac-Events-Report-Skidmore_lo.pdf

United States Fire Administration. (2015). Retrieved from http://www.usfa.fema.gov/

Dan Kerrigan is a 28-year fire service veteran and an assistant fire marshal/deputy emergency management coordinator and department health and fitness coordinator for the East Whiteland Township Department of Codes and Life Safety in Chester County, Pennsylvania and the Director of The First Twenty’s Firefighter Functional Training Advisory Panel. Kerrigan is a graduate of the National Fire Academy’s Executive Fire Officer Program and holds a Master’s Degree in Executive Fire Service Leadership. He is a PA State Fire Academy Suppression Level Instructor as well as an adjunct professor at Anna Maria College, Neumann University, and Immaculata University. Connect with Kerrigan at dkerrigan@eastwhiteland.org, on LinkedIn, or follow him on Twitter @dankerrigan2. Follow The First Twenty on Twitter @thefirsttwenty.

Dan Kerrigan is a 28-year fire service veteran and an assistant fire marshal/deputy emergency management coordinator and department health and fitness coordinator for the East Whiteland Township Department of Codes and Life Safety in Chester County, Pennsylvania and the Director of The First Twenty’s Firefighter Functional Training Advisory Panel. Kerrigan is a graduate of the National Fire Academy’s Executive Fire Officer Program and holds a Master’s Degree in Executive Fire Service Leadership. He is a PA State Fire Academy Suppression Level Instructor as well as an adjunct professor at Anna Maria College, Neumann University, and Immaculata University. Connect with Kerrigan at dkerrigan@eastwhiteland.org, on LinkedIn, or follow him on Twitter @dankerrigan2. Follow The First Twenty on Twitter @thefirsttwenty.

Jim Moss has been in the fire service for over 10 years and is currently a lieutenant with the Metro West Fire Protection District of St. Louis County, Missouri. He is a proud contributor to firefightertoolbox.com and firetrainingtoolbox.com. He possesses a BS of Fire Science from Columbia Southern University. His certifications include: Fire Officer I/II, Fire Instructor I, Vehicle Rescue Technician, Driver/Operator, and Hazardous Materials Technician. His fire service passions include mentorship, leadership, fitness, and training. Connect with him on LinkedIn and Twitter @jimmoss911.

Jim Moss has been in the fire service for over 10 years and is currently a lieutenant with the Metro West Fire Protection District of St. Louis County, Missouri. He is a proud contributor to firefightertoolbox.com and firetrainingtoolbox.com. He possesses a BS of Fire Science from Columbia Southern University. His certifications include: Fire Officer I/II, Fire Instructor I, Vehicle Rescue Technician, Driver/Operator, and Hazardous Materials Technician. His fire service passions include mentorship, leadership, fitness, and training. Connect with him on LinkedIn and Twitter @jimmoss911.