By ERIC HASKINS

Just as with politics and religion, fitness is a topic that can easily get a rise out of firefighters around the kitchen table. Some may even consider it a “bad word.”

- Twenty Hose Exercises for Firefighter Functional Fitness

- 15-Minute Mobility to Reduce Fireground Injuries

- Firefighter Fitness on a Budget: 10 Items for Less Than $1,000

- Five Steps to a Firefighter Fitness/Wellness Culture

However, with 102 line-of-duty deaths in 2020 and an estimated 60,750 firefighter line-of-duty injuries occurring in 2021, avoiding this topic like the plague is proving to be costly. The National Fire Protection Association estimates that 17,200 injuries—28 percent of the total injuries—resulted in lost time and thus impacted our ability to serve the citizens we swore to protect.

When it comes to the fire service, it takes a significant amount of time and money to train and equip our members for the job. From personal protective equipment to staffing our recruit academies, we are heavily invested in our members from the very beginning of their careers because we cannot carry out our mission without them. So, how do we continue to invest in our firefighters and keep them healthy so they can continue to serve our communities for the lifespan of their careers? Well, pardon my language, but we need to talk about “fitness.”

The Three Key Factors

The concept of fitness is rather vague, and when it comes to its application in the fire service, it can get lost in a battle of semantics. For some, fitness reminds them of their time in the academy and how it was used to “punish” them for forgetting to check for “swivels, gaskets, and threads.” Others may relate fitness to the neighborhood gym or that expensive treadmill collecting dust in their garage. Regardless of how you identify with fitness, it requires a closer examination of three key factors that contribute to our fireground performance, which follow.

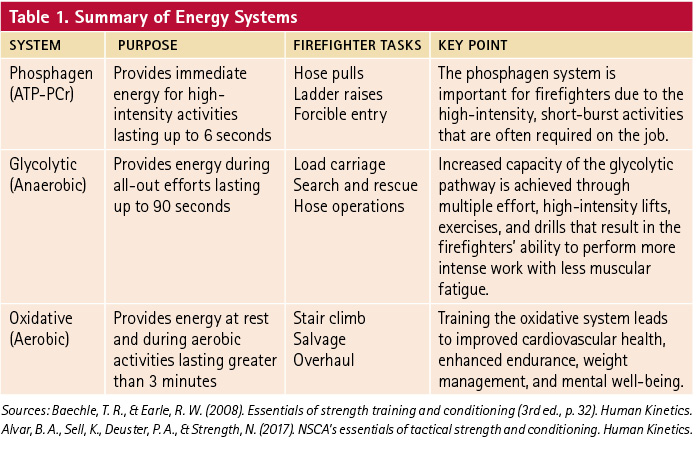

Work capacity. This is the general ability of the body, as a machine, to produce work of different intensities and durations using the appropriate energy system. Different intensities and durations require different energy systems to produce adenosine triphosphate, which is the currency our body uses to do work. If the intensity of the event is extremely high and the duration is short (0 to 6 seconds), your body will primarily use the phosphagen system. If the intensity is a bit lower but the duration is a little longer (6 seconds to 2 minutes), your body’s primary energy system will use glycolysis. And, if the intensity is low and the duration long (> 3 minutes), the primary energy system will be oxidative. These three “engines” are not mutually exclusive but work in concert with one another depending on the event or, in our case, the incident and the tasks needing to get done. We can develop and improve these engines by means of metabolic conditioning. The better our work capacity, the better we will be able to perform, regardless of the intensity and duration of the incident.

(1) Training in gear is the bridge between our work in the gym and our performance on the fireground. (Photos by author unless otherwise noted.)

(2) Your level of preparedness is determined long before your next call comes in. (Photo by Jimmie Lewis.)

Fitness. In this case, fitness refers to the specific ability to use this work capacity to execute a given task under particular conditions. In general terms, fitness may be defined as the ability to cope with the demands of a specific task efficiently and safely. This means fitness is uniquely specific. A runner who trains for a marathon and successfully completes the race efficiently and safely would be considered “fit.” Likewise, a powerlifter who can effectively lift the heaviest weights at a meet without getting hurt would also be considered fit. However, if you were to put either one of these athletes in the other’s event, they would most likely perform poorly in comparison to the rest of the field because they lack the fitness to cope with the demands of that specific event.

As it applies to the fire service, the fitness we require is broad and must be able to cope with the demands of the fireground. Being “fit for duty” means having the capacity to meet these demands, regardless of the task. The task is determined by the citizens we serve when they call for us, and it’s our duty to show up and mitigate it. Fitness for the fire service is developed with proper strength and conditioning programming designed specifically for firefighters.

Preparedness. This refers to our ability to express fitness at any instant. It should come as no surprise that firefighters were more likely to be injured at fireground operations than any other type of duty. Unlike organized sports, we do not have a predetermined “season” with games and practices scheduled ahead of time so that we can prepare accordingly to peak at just the right moment. We also do not have the ability to “warm up” prior to our next alarm. At a moment’s notice, we must be able to express our fitness to our fullest capability because the citizens we serve depend on us, and lives are on the line. This is what it means to be prepared. The degree to which you will be prepared will depend on the organization of your training and the methods you use.

(3) Lifting a maximal load safely requires discipline. Always maintain proper form and don’t ever sacrifice technique for more weight.

Designing Your Program

After examining the three key factors that contribute to our fireground performance, we now have the framework to design a training program that will not only improve our ability to do the job but also reduce the risk of injury or, possibly, death. Again, this is where strength and conditioning play a role. If injuries occur when a tissue’s (e.g., muscle, bone, ligament) strength can’t handle the load being applied, then, to reduce the risk of injury from occurring in the first place, improving the strength and endurance of weaker muscles is the best method for injury prevention. In general, we can increase strength by recruiting more motor units, increasing the rate or speed at which they fire, or making them bigger.

Most resistance training programs use what’s called the “Repeated Effort Method,” which is lifting a nonmaximal load to or near failure, resulting in bigger muscles. Bigger muscles can be beneficial for many by putting on some much-needed size and “body armor” in areas that may be prone to injury. However, in the fire service, we also need to be able to express maximal strength when it comes to lifting heavy objects or victims and explosive power when it comes to making the push down a hallway or performing forcible entry. To build these special strengths, we must turn to other methods. To build maximal strength, we must use the “Maximal Effort Method,” which is lifting a maximal load. This typically involves loads that are 90% or more of a person’s one-repetition maximum.

To build explosive power, we must use the “Dynamic Effort Method,” which is lifting a nonmaximal load with the highest attainable speed. These loads are often in the realm of 30% to 65% of a person’s one-repetition maximum. The keys to the Dynamic Effort Method are speed and acceleration. If the weight becomes too heavy and starts to slow down, you’re going to miss the intended stimulus and thus the desired outcome.

Traditional Western Periodization is a classic model with which most are familiar, whereas the intensity increases while the volume decreases. Commonly applied over a 12- to 16-week cycle, it finishes with a strength/power phase just in time to peak on a specific date or for a specific event. The downside of this model is that the residuals from the prior phases, like muscular endurance or hypertrophy, do not carry over or stick around for long and will leave the athlete ill-prepared for any event outside of the “peaking” window. This model doesn’t work well for the fire service because, as previously mentioned, we don’t have a known “event” or “competition” date for which we are specifically training. Our events are signaled by the next alarm bell, and they are going to keep coming, 24 hours a day, seven days a week, for the rest of our careers; this is why using something like “The Conjugate Method,” pioneered by Louie Simmons of Westside Barbell, has proven to be so effective for tactical populations. The Conjugate Method uses all three methods of strength training in conjunction with one another, year-round, so that the athlete or, in our case, the firefighter, is always prepared for the next run because he doesn’t have an “off season.” The Conjugate Method addresses our needs for all aspects of strength and preparedness.

(4) Forcible entry requires explosive strength, coordination, and accuracy. (Photo by Jake Ives.)

(5) It doesn’t have to be complicated to be effective.

Conditioning

Conditioning is all about developing our work capacity to meet the demands of the fireground. Studies show that heart rates of firefighters during interior structural firefighting operations can be as high as 164 to 183 beats per minute. Knowing this, we should design at least some of our conditioning workouts to deliver a similar stimulus using the same types of movement patterns commonly found on the fireground if our intent is to prepare accordingly. Whether it’s training in our gear with fire-specific tools and equipment or in a more controlled environment like the firehouse gym or an apparatus bay, we should take our bodies through a full range of movements that incorporate lifting/hinging, pushing and pulling, squatting, and loaded carries, all while maintaining elevated heart rates for sustained bouts or intervals with rest in between. The combinations are limitless, and not every workout has to leave you flat on your back. In fact, I highly discourage this if you’re on duty. However, every so often, train at the margins of your experience and ability if you want to prepare accordingly for what your next alarm might be.

Putting this all together, we should have a better understanding of fitness in the fire service. Instead of the “punishment” for which it was used in our academy when we were just starting out, we must reframe the conversation so that “fitness” isn’t such a “bad word” but rather specific to the demands of the job and designed around a well-organized strength and conditioning program. This, in turn, makes it simply an injury prevention and fireground performance training program. Approaching fitness with a better mindset and the knowledge of what it means to be fit for duty can give us a greater purpose behind our training. Who knows, you might even enjoy it, and you might even have a little fun.

References

1. Campbell RB, B Evarts, and JL Molis. (2022). United States firefighter injuries in 2021. National Fire Protection Association. Research, Data and Analytics Division.

2. Siff M. (1995). Facts and Fallacies of Fitness (6th ed., pp. 64–65). Human Performance Institute, South Africa.

3. Baechle TR and RW Earle. (2008). Essentials of strength training and conditioning (3rd ed., p.32). Human Kinetics.

4. Firefighter Fatalities in the United States. (December 1, 2022). U.S. Fire Administration. www.usfa.fema.gov/statistics/reports/firefighters-departments/firefighter-fatalities.html.

5. Frost DM. (July 29, 2017). Knees, back, shoulders…Not just a fireground problem – Performance Redefined. Performance Redefined.

6. Kurz T. (2001). Science of Sports Training (pp. 166–167). Stadion Publishing Company.

7. Baechle TR and RW Earle. (2008). Essentials of strength training and conditioning (3rd ed., p. 76). Human Kinetics.

8. Vladimir Mihajlovič Zaciorskij, and WJ Kraemer. (2006). Science and practice of strength training (p. 81). Human Kinetics, Cop.

9. Brennan C. (2011). The Combat Position. Fire Engineering Books.

10. Alvar BA, K Sell, and PA Deuster, et. al. (2017). NSCA’s essentials of tactical strength and conditioning. Human Kinetics.

ERIC HASKINS is a former U.S. Project Gold Snowboard Team member who competed internationally for six years in pursuit of Olympic Gold. Retiring in 2009, he played ice hockey for Boise State University while earning his bachelor’s degree in exercise science, specializing in exercise physiology. Haskins is a National Strength and Conditioning Association-certified strength and conditioning specialist, a tactical strength and conditioning facilitator, and a Westside Barbell Conjugate tactical coach. He is also a senior firefighter for the Nampa (ID) Fire Protection District, assigned to Truck 1 at “The Hornet’s Nest,” and was Idaho’s first graduate of the Georgia Smoke Diver program. Haskins is a co-founder of Brotherhood in Training and the head coach of Firehouse Strength & Conditioning, an online training program designed specifically for firefighters.