by KENNETH J. SCANDARIATO

The incident commander’s (IC’s) job as an “incident manager” has been consistently discussed and evolving since the birth of the American fire service. All too often, we continue to be reactive to the growing threats to our firefighters. Most of our innovations, changes, and mandates have been driven by the tremendous sacrifices made by our brothers and sisters. The changes we have embraced through trial and error have been hampered by tradition, complacency, and ego. Bad practices for firefighter survival continue to plague ICs to this day. Why?

Accountability

An important feature of the incident command system (ICS) involves controlling the access of personnel to an incident scene. All officers must be aware of the hazards involved in a specific incident and take the necessary steps to control access to areas under their supervision, to protect personnel from unnecessary exposure to existing hazards, and to keep unauthorized persons out of hazardous areas. The officer in charge inside the building is the intelligence officer for the IC. Without accurate, specific, and timely information flowing on a regular basis, preferably in reference to the 10-minute personnel accountability report (PAR), the IC has to wait until he sees some strategic, measurable, action-oriented, realistic, timely changes or eventually gets face-to-face with the crews as they exit the buildings. This is not a proactive way to manage the incident safely, forecast ahead for timely additional resources, or ensure that the safety of the crew is enforced by a working and proactive tactical plan.

There is a critical need to track the movements of personnel engaged in a coordinated tactical plan inside the structure while they are moving to locate, confine, and control the fire. There must be an accountability plan that all members on the fireground are acquainted with and use every time. It is the IC’s responsibility to ensure that an accountability plan is in place while the operation is developing and ongoing and, most importantly, during any strategy or tactical change.

The moment a firefighter breaks the plane from outside to interior operations, the IC generally becomes unaware of personnel positioning without a system. Tactical planning is sacrificed as a result of a lack of discipline on the part of the IC to ensure a plan is in place while the operation is developing.

Multicolored tag systems, electronic tracking (for departments that can afford them), and simple daily roster systems are all out there. A one-size-fits-all approach may fail for a myriad of reasons, including staffing availability, communications capability, training and experience, accountability system differences, and ownership.

All tactical plans rely heavily on the personnel as they arrive. When resources are not immediately on scene to address the identified priorities, all too often a critical task at the top of the IC’s list of things to address (life safety) will drive command to employ the next available body/crew without that person/crew’s formally checking into the scene. This is the beginning of the command “trap” that locks up many well-intended commanders. When we fail to record the decisions made in the initial phases of the incident, we lose control of the scene. The first tasks of the IC are to identify the strategy, develop a tactical plan, and assign the appropriate resources. The first priority is life safety, which many times goes hand-in-hand with incident stabilization. We lose these concepts when the IC does not ensure the documentation of the actions as the troops are directed to the greatest life safety problems. When the command process is not followed, command is sacrificed to freelancing.

Scenario

As the IC of a small department, you arrive to a well-involved building fire on floor 2 of a 100-year-old, 2½-story single-family, balloon-frame, open loft, 50 × 150 with eight units in townhouse configuration. Your size-up indicates you need a handline to the top floor [with a driver, an officer, and a firefighter (3); a vertical vent (3); water supply (3); and a backup line (3)-12 personnel total]. Unfortunately, the water is 2,000 feet away, and even with the available apparatus water, an additional supply will require additional help, thereby reducing your available interior staff to six firefighters. There are reports of people inside the building, and the fire is extending to the attic, evident by the smoke conditions issuing from the soffit line to the attic area. You arrive with five personnel, a truck, and a pumper. You request mutual aid from three area departments.

This is not a tactical discussion; it’s a leadership and discipline challenge. Command has to direct the situation, not the other way around. The ICS must be followed, including documenting the roster of responders and indicating their locations and tasks as assigned on the fireground. All too often, the IC will fall into the trap of assigning the next available crew to the most urgent need and sacrifice the process of documentation to the urgency.

A successful operation requires adequate staffing, including a command team, a water supply, equipment, and a structured action plan that has all the necessary ICS tools and boxes checked. Unless you are working in a department with a preassigned number of people in response, you will be shorthanded at the front end of every incident.

The IC has made the size-up, called for resources, and begins the wait for additional help. While waiting for the help, follow your process, and document your decisions. When resources are assigned, record the decision on a laminated 8½ × 11 clipboard with waterproof pen: “E2-Floor 2, SAR; Truck 1 vent; E3 # 3 floor, Attack.” Write it down. While you are waiting for the resources to arrive, take this time to record what you plan to accomplish. Some ICs become overwhelmed at this time because of the imbalance of resources to critical tasks.

I have always viewed the tag on the ring or board as a tool used at the end of the incident to indicate who was missing, not what the person’s position, placement, company, and function were. If your two-tag system ends up in a heap of tags on a ring without identifying the placement or function of the crew, this system will fail you when a firefighter calls a Mayday. These systems often end up as a collection point for tags instead of as an accountability tool.

Keep it simple. For departments with known daily staffing, the company officer or duty chief should completely fill out a shift roster according to department procedures before the start of the oncoming shift. The roster should be accurate and up-to-date, and there should be three copies. Two should be enclosed in a plastic page protector and carried in the chief’s vehicle; the other should be placed in a first-out rig.

For departments without permanent staffing, the tag system works well as long as someone assembles the tags and coordinates them with the placement and functions on the incident scene and keeps it current. Departments that must assign personnel as they arrive should identify the tasks to be performed by priority, assemble the arriving personnel into groups, and track the placement of the groups in the structure-for example, Vent group (V-1, V-2), Search (SCH team A #1 fl, SCH team B #2 fl) Attack line #1 (ATK1 1st fl), and so on. As long as everyone is trained to maintain unit/group integrity, this system will work. Make up your own shorthand recording system, and train everyone in the process. Keep it simple. Write it down.

Firefighting is a team effort. That’s why the accountability component should be trained on and enforced as part of the team’s responsibility. The IC has little knowledge of the position changes within the building during the operation. The company officer must fill in the information void for the IC by providing timely reports, typically during the PARs at designated intervals.

Mutual-aid companies must ascertain whether neighboring town departments have accountability procedures that will identify the roles and responsibilities of on-scene personnel assigned by the IC. Fire officers must have standardized information to use when delivering in-house training and conducting drills so that firefighters in a region will be familiar with the accountability system even when responding on mutual aid.

The Four Commandments of Accountability

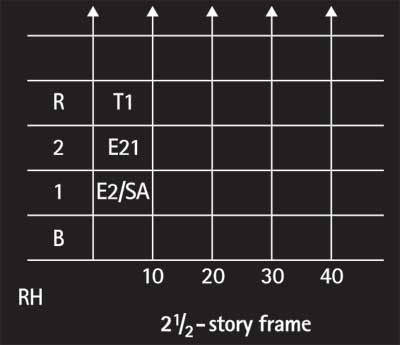

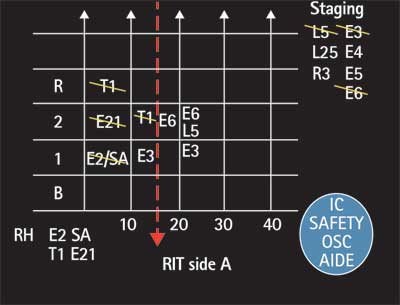

| Figure 1. Write It Down |

|

| The fire is on floor 1. The IC verbally assigns E2 and S/A to floor 1 for fire attack and search. E21 is directed to the floor above for search and extension, and the truck goes to the roof. “RH” indicates Rehab, when the crew member comes out for a bottle change; the 10-minute time frames indicate PARs, 10-40 minutes. |

All emergency response organizations must adopt an accountability procedure that works for small and large incidents. It involves assigning responsibilities to all working parts within a fire building.

- It is the responsibility of the IC to know the location and function of every crew on the fireground. This is completed by initial documentation on assignment at the command post (CP).

- It is the responsibility of every company officer to ensure that the IC knows his crew’s location and function at all times.

- It is the responsibility of every company officer to know the location and function of every person assigned to his crew at all times.

- It is the responsibility of every firefighter to ensure that their company officer knows their location and function at all times.

On your PARs, crew leaders shall report placement within the building. Your first PAR allows the IC an interior glimpse of your forward progress and crew positions within the structure. Your second PAR is used for tactical planning and exterior size-up. These two timed benchmarks verify the initial strategy was correct, gauge your resources against known issues, and define a clear view of the risks taken thus far. If you use this information in conjunction with the “read” of the building from the A/C sides, the IC will have the clearest picture of the current conditions, actions, and needs.

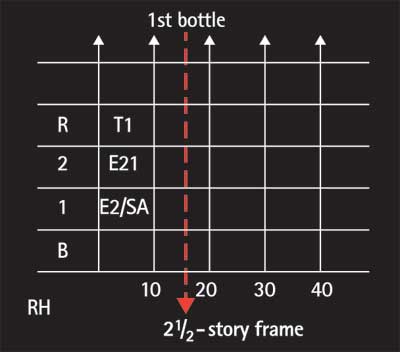

| Figure 2. The Use of One Bottle |

|

| The same graph, on the 10-minute mark, reaffirms the positions of the crews when notified by radio or face to face and notes the first bottle change. Anywhere between the time lines is acceptable. It’s more about noting that they have been through one bottle than noting the time. |

Training

It will take time for the system to become embedded in the minds of all working crews on the incident scene. Practice it at every incident. Enforce the requirements of communication to and from command. There should be no transfer of personnel from one company to another on the emergency scene without positive communication between the two affected company officers and incident command.

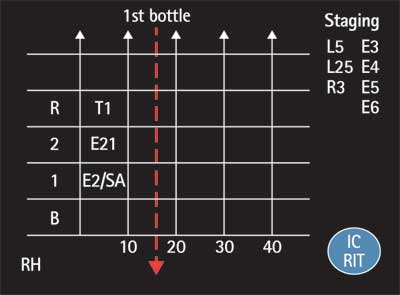

| Figure 3. Need for Resources |

|

| A need for greater resources is identified. The upper-right-hand corner indicates who is coming. The lower-right-hand corner is used to build the command team. |

Companies should remain intact with all fire personnel operating in the same area. If a company must be divided to perform required functions, the sector/division officer must maintain control of all firefighters assigned to him. When personnel are relieved for rest and rehab, on notification, the IC notes the location and function of the crew. After being relieved from rehab, all personnel must return to the CP for reassignment. Command must also be notified of any firefighters being treated at the EMS/Rehab sector or being transported to a medical facility.

All personnel called back, whether arriving in reserve apparatus, city vehicles, or individually in personal vehicles, need to report to the IC or staging officer and be logged in before being assigned.

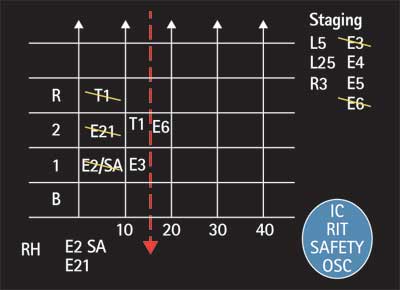

| Figure 4. Change in Assignments |

|

| T1 is reassigned on “Vent Completed” to floor 2; E2, E21, and S/A are out for rehab; and the IC has ordered E3 and E6 from staging to the areas noted. This takes seconds to indicate. The downward slash indicates movement from the original position to new positions or to new assignments. The companies have moved to rehab and out of staging (E2, SA, E21, E3, E6). |

If you rely on mutual aid, you should have a system in place, and responding agencies must be aware of and trained on your expectations of documentation. The documentation should include at a minimum the company designation, crew leader (officer), and last names of crew members. This will take time; adjust the risks within your current action plan, and take the time necessary to ensure IC control and awareness.

Mutual-aid companies responding directly to an emergency scene should provide an officer with the IC. A Cover Company Accountability Sheet will work well here to ensure accountability of mutual-aid personnel and to build the command team.

PARs will be necessary to determine if everyone is accounted for during an emergency incident. The IC will initiate a roll call by announcing the company or sector/group/division designation first and then waiting for a response from that company. The personnel roster can be the checklist for the IC.

How We Do It

Take a 2½-story, one-family residential building in Anytown, USA. You arrive with three pumpers (E21, E2, Squad A), one truck (T1), and one IC vehicle.

For accountability purposes, all responding companies should have prearranged assignments; but if you do not, this system will still work using the groups-to-task method. Map out the structure by drawing a simple grid on a piece of paper with a waterproof pen. Keep the system simple.

If we were to continue with this operation, you would have a complete tracking of the personnel movement within the building. The beauty of this system is that it takes seconds to do; it’s low tech, current, and relative to attending to the changing mission priorities. Train your personnel to be active partners by adhering to rules 1-4. Looking back at Figure 5, we now have the ability to identify the placement of all crews assigned within the building. If a Mayday were to occur, the IC would have a clearer picture of where to deploy the rapid intervention team based on the charted assignments. Write it down.

| Figure 5. Additional Activities |

|

| Fire indications continue the need for activities in the areas noted on floors 1 and 2. The IC has now ordered a second PAR. Truck 1 is now in rehab, and you have assigned E6 and L5 to floor 2 and E3 to floor 1 from staging. On the second PAR, take the time to “read” the building. Is the smoke color, velocity, or density changing? These indicators along with your face-to-face discussions with the officers reporting to rehab verify that your tactical plans are working or indicate that they are in need of adjustment. The command post indicates the IC, safety officer, operations section chief, and command aide are on scene. The rapid intervention team is on scene on side A. |

Personnel-deficient departments are making a good initial push once crews are assembled. The Achilles heel of the initial attack is having the necessary reinforcements available to sustain an aggressive attack for a successful (safe) outcome. The pressure to maintain the edge of opportunity forces the IC to sacrifice documentation to the urgency of the moment for deployment issues.

The IC’s initial decisions are usually consistent with conventional tactics for a given strategy. Our initial push is to direct actions that preserve life safety; our Achilles heel is failing to adhere to the principles of accountability during critical moments in decision making. As the IC, you must continue to ask, “If they get into trouble, where will I send the RIT?”

Take the time to train your personnel on your needs as an IC to ensure their safety. Make it a standard operating procedure that they inform you of the PARs of their position as well as for all accounted. Proactive documentation supports a successful tactical plan and ensures that the right help gets to the right place in time. Remember, we do not fight fire; we fight time progression. Documentation that is current, accurate, and specific will enable greater fireground control and fireground accountability for your operation and the safety of the interior crews.

KENNETH J. SCANDARIATO, EFO CFEI, is chief/fire marshal of the Norwich (CT) Fire Department. He is a 38-year veteran of the fire service and has been in a command position for the past 22 years. He has a BS in public administration, is a graduate of the Executive Fire Officer Program, and is a certified explosion investigator.

Fire Engineering Archives