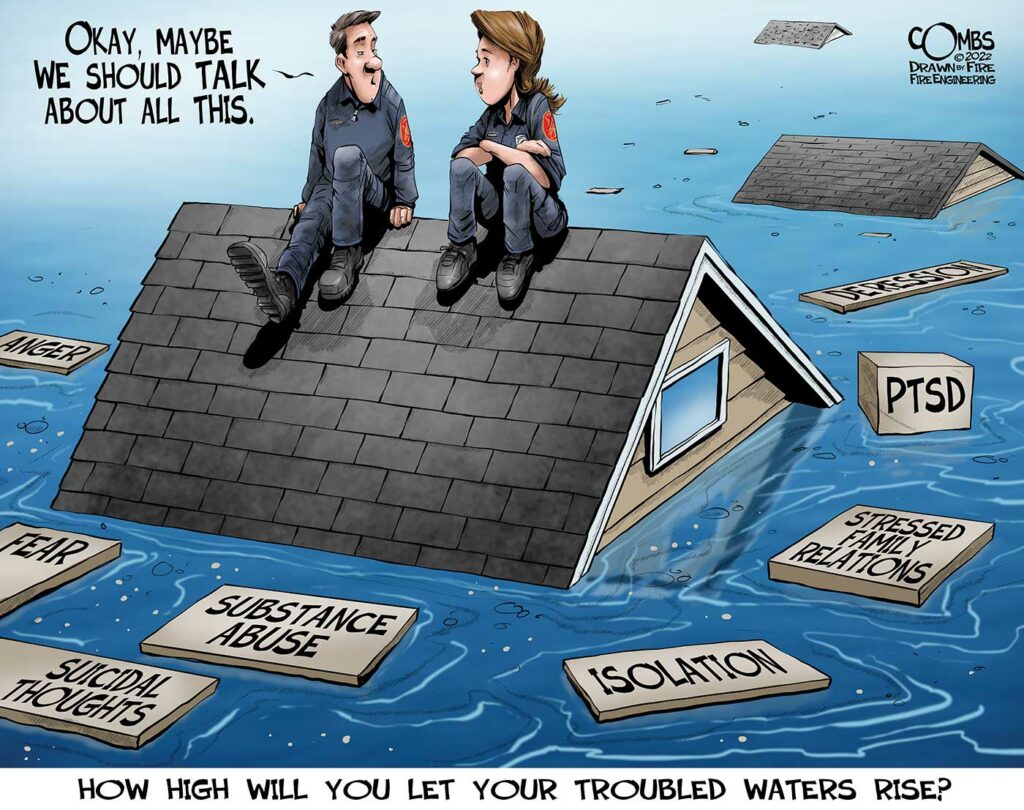

I recently had a raw conversation with a fellow firefighter where we talked about an incredibly difficult season of his life. We’ve all had them, and many of us may even go through multiple episodes of them. It’s the “cost of doing business” in this job.

He caught me off guard when he causally and quietly told me that during that time he etched his name on to a bullet; thinking that either he would end up using it to leave this season of life or take it and toss it when the season was over.

I sat in silence with my thoughts for a moment before replying. The casual manner that he used to relay this information struck me, but mostly because I had already seen it before.

I can still clearly remember the day a soldier-turned-nurse joked with me about having a suicide plan while we stood in the ER. He saw my reaction, shrugged, and said: “Stephanie, you’re a first responder. All of you have a secret exit plan.”

RELATED

- Helping Firefighters Deal with a Traumatic Incident

- The Power of Peer Support in the Fire Service

- Commentary: The Mental Mayday

- It’s Not The Calls: Firefighter Mental Health and Organizational Leadership

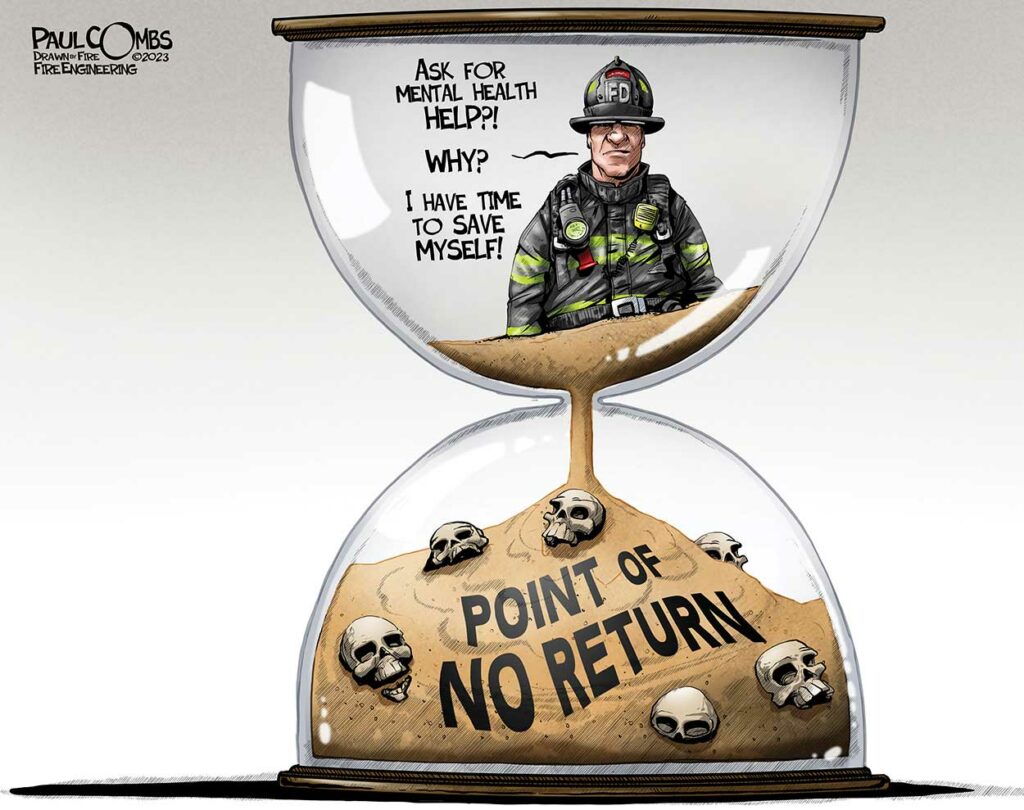

The realization hit me like a brick, and it stuck with me for the next few days. We talk often about the need to prevent first responder suicides, but do we ever dissect WHY that path can be such a rapid descent for us?

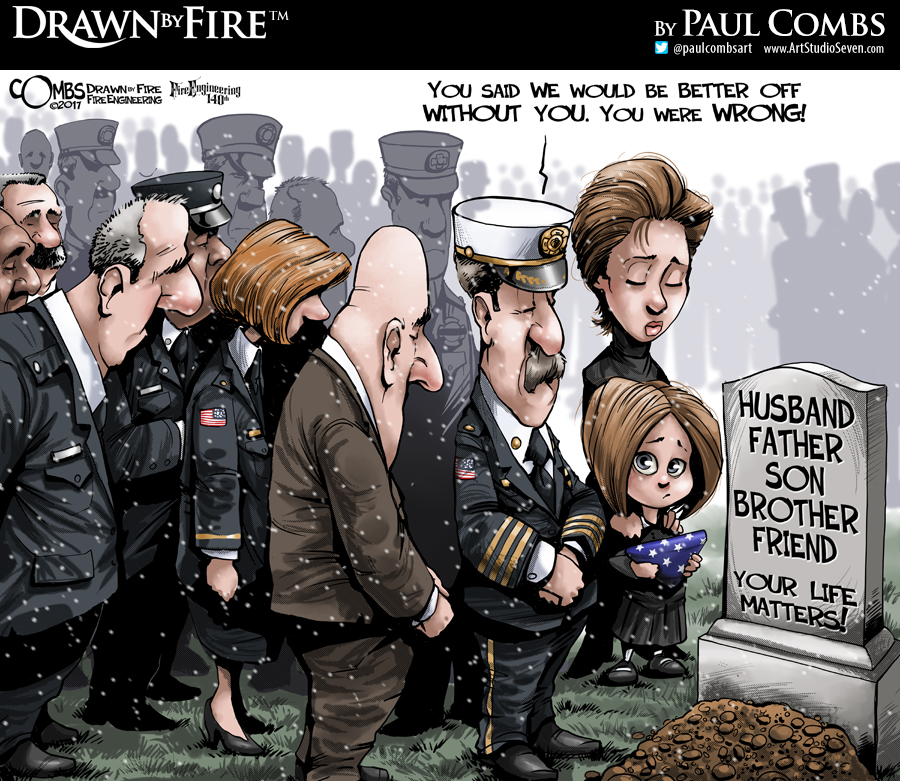

The nurse wasn’t entirely wrong. That firefighter’s approach wasn’t the first I’ve seen. First responders are in the unique position where we are the ones to find someone who has passed from suicide and then must handle the aftermath. We see the methods, we may be privy to the reason, and we see the shock and grief of the family. The grief that comes from loved ones taking their life is jarring for anyone who is involved on the call. Over time, to protect our own mental health, we begin to sort of accept it as a natural way of death.

We’ve seen the devastation, and we have also seen very up close that someone has managed to escape the pain they were in…but at what cost?

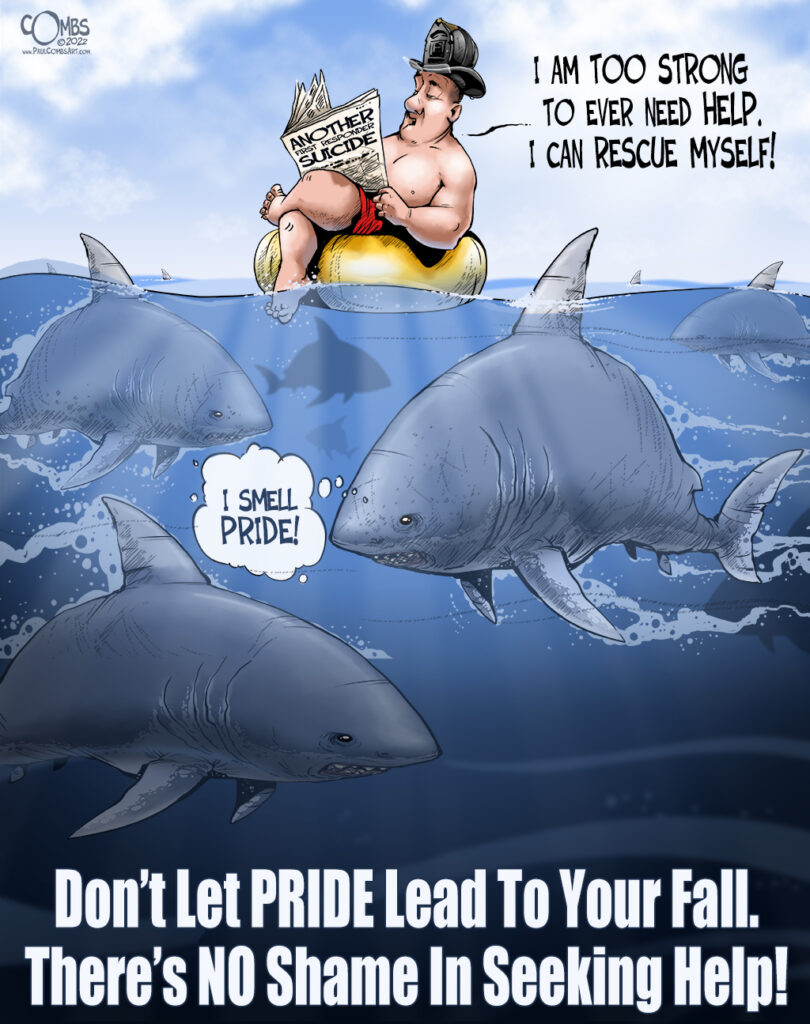

There’s something pretty amazing about being new and running those first few years of calls. Some sort of wonder, pride, ownership, shock…I wish I could find a word to encompass the feeling of that beginning experience. Along with that unique feeling comes the darker, sobering calls and the need to protect our minds. We find a way to normalize what we see. We try to take the shock out of it.

And that’s exactly what we do with the painful reality of suicides. It becomes a natural form of death for us. We eventually place it on the same shelf as passing away from a heart attack or stroke. It’s a simple way to take the heartbreak out of it. We normalize it, and we accidentally become one step more comfortable with it. Chances are we’ve all lost someone in our department to it.

In a career where our risk of suicide is double that of the general public, our mental health resources need to be doubled. Those resources also need to be educated and realistic. Working with us requires an understanding that we’ve probably held an entire legion of inner demons at bay for far too long, and our ability to create and carry out an “escape plan” is faster than most mental health professionals are prepared for.

If we’re going to be better about saving our own, we’re going to have to become better at acknowledging that we can no longer “normalize” all the ugliness and heartache that we see on calls.

Do we need an entire peer team to respond every time we run a suicide call? No. Do we need to pause and consider that for our own safety we can’t “normalize” it to digest it? Probably. Putting in that mental work might just save our life or someone else’s, and at the end of the day, isn’t that our mission as firefighters?

A month after our initial conversation, the firefighter and I sat down again to talk. How do we effectively take a line that he had stepped over and move his line of safe thinking backwards? How could we bring a little bit of “average reality” back into a world where our baseline is far from average? We’re still working on figuring out that answer.

Each year we grow and improve as a fire service. We realize more and more that just because we can do and see hard things, it doesn’t mean we need to “normalize” them to be able to digest what we’ve seen. Let’s find a way to teach ourselves and the next generations that nothing about this job is normal—nothing—and then teach them early on how to properly handle that weight.

Stephanie White is a 19-year veteran of the fire service, and has spent the past 17 years as a professional firefighter/paramedic in a metropolitan fire department. Throughout her career, she has been actively involved in firefighter health and safety as a personal trainer, cancer awareness educator, and a trained mental health peer.

This commentary reflects the opinion of the author and does not necessarily reflect the opinions of Fire Engineering. It has not undergone Fire Engineering‘s peer-review process.