FIRE ON BOARD!

FIRE REPORTS

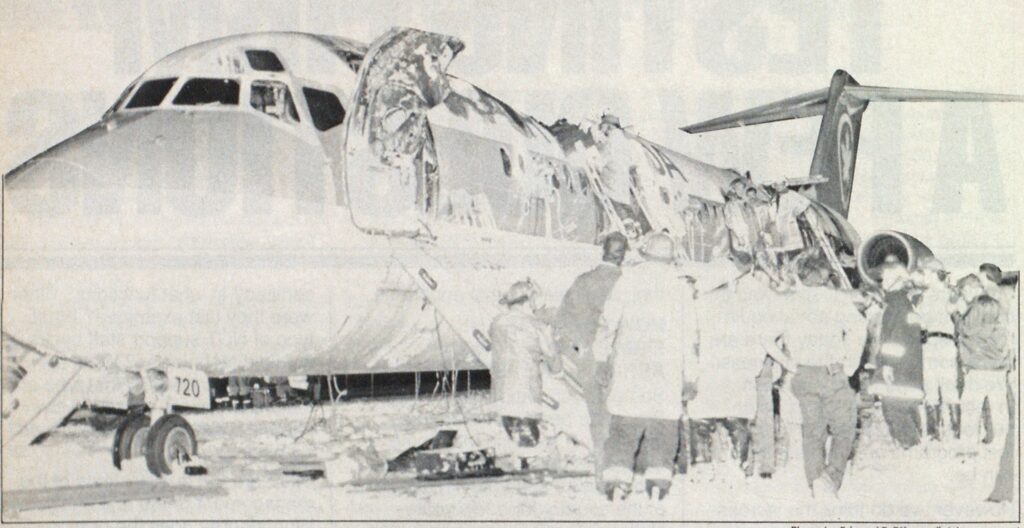

Photo by Edward F. Effron, all rights reserved

Thirty seconds made the difference between life and death for 41 passengers and five crew members aboard Air Canada’s DC-9 that made an emergency landing at the Greater Cincinnati International Airport last June 2. Twenty-three people died as the fire raced through the plane.

At 5:15 p.m. on June 2, Air Canada Flight 797 with 41 passengers and five crew members on board departed from DallasFt, Worth Regional Airport bound for Toronto, Canada. An hour and a half later, a fire was discovered in a rear lavatory.

The first indication the pilot had of trouble was when the circuit breakers for this lavatory tripped and could not be reset. Shortly thereafter, the flight attendant reported that after emptying two fire extinguishers, the fire could not be put out. The pilot began making Mayday calls for an emergency landing at the closest airport. The plane was at an altitude of 33,000 feet and approximately 25 miles southwest of Greater Cincinnati International Airport. This airport encompasses 5000 acres in rural northern Kentucky, 15 miles south of downtown Cincinnati, Ohio.

Transmissions between Captain Donald Cameron and Gregory Karam, controller at the Cincinnati Tower, remained calm although the situation deteriorated rapidly. As flight attendants moved the passengers towards the front of the plane, the cockpit began filling with smoke. Within minutes, the instrumentation failed, leaving the pilot only a horizontal indicator to aid in landing. He had no time to give the air traffic controller any information concerning the amount of fuel or number of people on board.

The fire department at the airport was notified at 7:11 p.m. that a jet would be landing on Runway 36 with smoke coming from the rear lavatory. Realizing that the rapidly descending DC-9 had overshot Runway 36, the controller guided it into a left turn and onto Runway 27L. Already situated for the landing on Runway 36, the fire fighters repositioned their apparatus and were in place when the plane touched down at 7:21 p.m.

Aware of the need for a quick stop, the pilot locked his brakes and the resulting friction blew all of the tires. Only that and black smoke billowing from the fuselage gave any indication that something was wrong. No flames were visible but police, and fire personnel on the scene could see the paint on the sides of the plane just forward of the engine beginning to blister and turn brown then glow cherry red.

Before fire fighters could get their 1 ½inch lines into the plane, the emergency exits above the wing opened and people tumbled out. Although most suffered from smoke inhalation, there were no life-threatening injuries and airport buses transported them to a terminal. The 30 seconds that elapsed during this evacuation was the difference between life and death. Eighteen passengers and five crew members survived the fire without serious injury; 23 passengers lost their lives.

Fire Fighter Mark Bailey, manning the turret on one of the crash trucks opposite the nose of the plane, noticed that the copilot, who had exited via the cockpit window, was pointing back at the plane. Inside, the pilot appeared to be in a daze, wandering away from the open window. Bailey quickly turned his turret, which was shooting a deflected stream of foam, through the window. The overspray revived the pilot long enough for him to escape the burning plane.

—wide world Photos.

Seconds after the last surviving passenger exited, fire raced through the plane, apparently accelerated by the oxygen from the open exits. Fire fighters moved in to extinguish the blaze.

Apparatus response

Upon receiving the alarm from the control tower, the eight members of the Greater Cincinnati International Airport Fire Department put their disaster plan into operation. Chief Kenneth Luxenberger was notified at home of the incident. Hearing the transmission on his portable radio, Assistant Chief Ron Reeser responded directly to the fire station at the airport to handle communications.

Captain )ohn Horton, who was in command until the arrival of Luxenberger, drove the quick response vehicle containing 450 pounds of dry chemical, 100 gallons of AFFF and light rescue equipment to a point where he could follow the DC-9 down the runway. The two Walters crash trucks, one with 500 gallons of AFFF, the other with 500 gallons of protein foam and each holding 3000 gallons of water, took a position farther down the runway. The response also included a 1000-gallon Seagrave pumper manned by Lieutenant Dave Bullock, Ron Becker and Tony Martin and a 100-foot quint aerial truck equipped with 300 gallons of water and 1200 feet of 2 ½-inch hose.

On the runway after the plane landed, the two crash trucks and the quint were located at the nose of the plane and the pumper was stationed behind the tail section where fire fighters removed the cone for easier access. Bullock and his men on the pumper took a 1 ½-inch line up the ladder for an interior attack while the crash trucks foamed the aircraft both to extinguish the fire and to act as protection against fuel tank leakage. Ten minutes later, with the fire almost knocked down, they ran out of water. The fire again began to build and accelerate.

Bringing Down a Burning Jetliner

Indianapolis Traffic Control: Got an emergency for you—Air Canada 797.

Karam (Gregory Karam, air controller at the Greater Cincinnati International Airport): Radar contact. OK.

Indianapolis: OK. He’s cleared to five right now. He’s got a fire on board.

Karam: (to tower) … I need the trucks for an Air Canada with a fire on board, landing runway 36. Air Canada jet with a fire.

Air Canada Flight 797: Approach, Air Canada 797, we’re on, uh, uh, Mayday, we’re going down.

Karam: Air Canada 797 … can you make it to the airport?

Flight 797: Canada 797, that’s affirmative.

Karam: Roger, plan runway three six ILS and the equipment has been alerted, do you have time to give me the nature of the emergency?

Flight 797: We have a fire in the back washroom and it’s, uh, we’re filling up, uh, with smoke right now.

Karam: Understand, sir, and say type of airplane, number of people on board and amount of fuel.

Flight 797: OK, we’ll copy that later. I don’t have time right now.

Karam: Are you heading zero nine zero, Air Canada 797?

Flight 797: We have no heading, we have no instrument, all we have is an horizon right now.

Karam: Can you give me a heading. Air Canada 797?

Flight 797: Stand by, we’ll try.

Karam: Air Canada 797, if able, turn left.

Flight 797: Air Canada 797 turning left.

Karam: Continue left turn, Air Canada 797.

Flight 797: We don’t see the airport.

Karam: Understand, sir. Advise me when you’re VFR conditions (when he can see well enough to fly without instruments).

Flight 797: We’re VFR now. We do not see the airport.

Karam: Understand. I’m turning you (toward) the airport, Air Canada 797.

Karam: Air Canada 797, you are cleared to land on runway 27 left…

Flight 797: Cleared to land. We don’t see the runway.

Karam: All right, sir. Your present heading is taking you to the field ….

Flight 797: Canada 797, where’s the airport?

Karam: Twelve o’clock and eight miles …. Air Canada 797.

Flight 797: OK. We re trying to locate it … advise people on ground we’re gonna’ need fire trucks.

Karam: The trucks are standing by for you, Air Canada. Can you give me the number of people and amount of fuel?

Flight 797: We don’t have time. It’s getting worse here.

Karam: Understand, sir. Turn left now and you’re just a half a mile north of final approach course.

Flight 797: OK. We have the airport.

Flight 797: OK. It’s a patch fire and we’re getting smoke.

Karam: (to tower) You’re gonna’ have to have the trucks come right up to him. He got smoke and fire on board.

Karam: Air Canada 797, the equipment is waiting for you. You need not acknowledge further transmissions from me, Air Canada 797, you are cleared to land. You are four miles east of the airport.

Karam: (to tower) Let me know when he lands please.

Tower: He’s landed.

Karam: OK.

Horton had requested a move-up response at 7:23 p.m., two minutes after the plane landed. Since the airport is located in a rural area, a plan for mutual aid using 12 surrounding volunteer companies and the City of Covington, Ky., had been worked out to deal with aircraft disasters. The plan calls for Covington to dispatch the companies that then respond to the fire station at Greater Cincinnati International Airport where they are deployed as needed.

In this particular incident, several of the companies directed by police officers went down Tower Drive to the fire scene. Hebron and Pt. Pleasant, first mutual-aid companies to arrive, quickly supplied the crash trucks with additional water by dropping their tanks.

The Erlanger Fire Department’s pumper arriving at 7:45 p.m. was advised to lay its 5-inch hose from the nearest underground hydrant to Hebron’s pumper. Greater Cincinnati Airport has four hydrants on 12-inch mains located underground for water supply to fire apparatus.

Prior to Erlanger’s arrival, the 2 1/2-inch line from the airport’s quint had been laid to that same hydrant but not charged. Due to the low pressure on this line, Erlanger broke it running a 3-inch line to the hydrant and connected its pumper to the 2 ½-inch hose to provide more water pressure. At 7:57 p.m., Erlanger charged both the 5-inch and 2 ½-inch lines.

The other move-up companies now on the scene began laying a line to the next nearest hydrant, approximately 4000 feet to 5000 feet away. But before the lay was complete the fire was out. The fire had ventilated itself through the roof and with the water supplied by the 5-inch and 2 ½ -inch hose lines, fire fighters extinguished it in 15 minutes.

The move-up response provided 11 rescue squads and nine pumpers from 12 area fire stations including the City of Covington. Reeser handled communications at the airport fire station with Ft. Mitchell and Crescent Springs acting as back-up units while Luxenberger was in command at the fireground.

Once the fire was out, it became apparent that no additional squads were needed. Luxenberger moved all rescue squads at the fire scene to an adjacent taxiway. Erlanger and airport fire fighters took 1 ½-inch lines inside the plane to check for hot spots. The bodies of 23 passengers were found in various positions, some still fastened in their seats. Notified of the fatalities, the National Transportation Safety Board sent investigators from Atlanta. The plane could not be moved pending their arrival. Attending medical personnel with the aid of Fire Fighters Tim Cook and Barry Alexander began to tag and stake the bodies.

The specially equipped mobile communication post supplied the items necessary for marking the location of the bodies and the body bags and cots used in transporting them to the temporary morgue in the field maintenance building. This 40foot disaster trailer capable of handling 200 injured or dead was designed by Fire Fighter Bill New after the Bevery Hills fire. When the bodies had been removed, other than having fire department personnel on the plane at all times, the fire fighters’ job was done.

A rule-making process to require fire-blocking material on airliner seats was expected to have begun last month.

In testimony before a House panel, J. Lynn Helms, head of the Federal Aviation Administration, said that “seats are by far the largest contributor to a cabin fire.” Three-year tests on the fire-blocking materials were completed early this year.

The fire safety layer would be installed on seat bottoms and backs between the outer fabric and the flammable polyurethane foam that forms the main seat contours.

Helms estimate that it will be three to four years before the improved seats are in use, having to first complete the rule-making process and the production of the fire-retarding materials.

Helms also plans to start similar rule-making procedures to require installation of wall and ceiling panels with improved flame resistance. He estimated that tests to perfect these safety panels would require at least a year, and he hopes that the rulemaking process could begin by Dec. 1984.

According to a New York Times report, Helms also set Dec. 1984 as a target date for a rule to require the use of a fuel additive designed to curb post-crash explosions by minimizing the tendency of fuel to break up into highly volatile mists.

Aftermath

The 26 members of the airport fire department all have a minimum of four years military experience and specialized crash rescue training. But this was the first time in the United States that a plane landed intact with an interior fire and fatalities. Reeser stated, This was an interior fire on board an aircraft. It’s easier to fight a crash-related fire because it’s like an egg breaking open; everything’s lying right in front of you. This was similar to a structure because it’s man-made like a building; the only difference is that it moves and flies.”

The National Transportation Safety Board is conducting an investigation into the cause of the fire and why 23 people died. Ironically enough, the question of whether or not the victims died from inhalation of PVC fumes is being raised. In May 1977, just a short distance from Greater Cincinnati International Airport, the Beverly Hills fire took the lives of 165 people. Litigation involving PVC poisoning in that fire is still pending.

—photo by Gary Auffart