BY JOHN RUSS

No one intends to make the wrong choice or do the wrong thing. When it’s time to act, we believe our actions or decisions are right. However, depending on rank, it’s possible we do make mistakes regularly largely because we don’t receive the necessary feedback. As importantly, we also have leaders who are timid about providing necessary feedback to their personnel. How do we resolve this communication issue? By having difficult conversations, you can help to coach and mentor your personnel for positive change.

- Seven Guiding Principles for Setting Upfront Expectations

- What Does It Mean to Be Accountable to Your People?

- Courage Under Fire Leadership: 15 Considerations Before Promoting

- Buddy to Boss: Leading with Integrity and Respect

To preface, I work in a department where our firefighters and company officers come to work to do a good job. We rarely, if ever, have bad actors who do something so egregious that they require immediate termination. The focus of this article is to help coach you on how to address slipping performance. You may need to look inward at your own leadership style and behavior. Keep in mind that nobody can tell you exactly what to say during a difficult conversation. Effective communication during difficult conversations happens through personal growth and leadership skills that you develop over time.

Before the Conversation

Before you open your mouth, you need to do some relationship building. It’s like working a commercial structure fire. With a little preplanning, you can have a lot more success. When you mentor new company officers, those new officers must feel that you are looking out for their best interest. That’s key. If they don’t feel safe discussing vulnerabilities with you, you will struggle to reach them and effect change. As a supervisor, to have this conversation you need to be approachable.

To become more approachable, familiarize yourself with how intentions work. Intentions are a two-way street. Stress that your intentions are pure. Good luck having a meaningful conversation if you are perceived as being out to sabotage a career or place blame. Understand the new officers’ intentions as well. Remember, most firefighters don’t come to work to sabotage the organization. If you come across that issue, follow your HR department’s policies and procedures to get them out of the department. For the other 99% of firefighters, remember that they believed they were doing the right thing at the time. It’s only after the fact that we get the opportunity to learn from our experiences. Show some humility when conversing and assume they weren’t intentionally doing wrong.

Finally, set your expectations early for 360-degree feedback to build the relationship. Officers have often used the saying, “If you see something, say something.” You are a senior fire officer, and they may be newly hired firefighters. It’s unrealistic to think that “see something, say something” is all that needs to be said about bringing up potential safety issues or disagreeing with you about a decision. Let them know when and how to talk with you about feedback on your supervision strategies. Who really knows your supervisory skills better than those whom you supervise? If you aren’t getting any feedback, are you sure that you are doing everything right all the time?

Timing is also key. You must have emotional intelligence and recognize your and their emotions before saying something. When you’re angry, the natural reaction is to address the issue immediately with a harsh tone. It may be best to give yourself a second to take a breath. If they are visibly upset about a certain event that went south, allow them to take a breath and calm down prior to trying to have a coaching moment. This doesn’t mean pushing off the conversation to the next shift, month, or annual evaluation. It needs to be relatively soon after the issue pops up. Just make sure you and they are in the right emotional state to have a learning conversation.

You should acknowledge these feelings as well. Know where you are emotionally. If you are having a bad day or are in the middle of family drama at home, recognize that you may not have the capacity to keep an impartial, level head. There isn’t anything wrong with letting them know your feelings about the issue, either. We aren’t robots. You are allowed to get mad or embarrassed about their actions, just like they are allowed to feel similarly. Recognize that emotions will be part of the conversation. Don’t be a robot.

If you are expecting an argument, and your goal is to persuade change, know that you must understand their point of view to change it. Arguing without understanding is unpersuasive. This may require you to do more listening than talking at first. Be prepared to really listen to their side of the story. One of the hardest things as a supervisor is to really listen to understand, not listen to respond. Set rules for yourself to listen intently and allow for a pause in the conversation before trying to say something about their beliefs.

Finally, before starting the conversation, take a long, hard look in the mirror. More than likely, you, as their supervisor, contributed to this problem either by lack of training; not making sure your expectations were clear; not having this discussion much, much earlier; and so on. In nearly every case, you can find some fault in your leadership that led to having this conversation. If you haven’t read Extreme Ownership by Jocko Willink and Leif Babin, pick up a copy. Be vulnerable. Shared responsibility doesn’t mean it all lands on your shoulders alone. However, letting them know areas where you plan to improve as a leader to ensure they get back on track will help with positive change.

Know your goal prior to having the conversation. If you are trying to place blame on something they did wrong, it’s not really a “conversation.” Fill out the disciplinary paperwork, have them sign it, give them the blame, and move on. Just know little learning has occurred from a simple write-up. If you are trying to impart learning or change behavior, understand the long-term goal.

As I mentioned, you must know their story to have a learning moment. Every story has three “truths”: yours, theirs, and what really happened. If you were only told of an incident that didn’t go well, you would envision a story in your mind about it. Even if you witnessed the event, you would assume the intentions or thoughts that led to the decisions or actions. Those are based on your own knowledge, skills, abilities, education, and training. These are biased. They also have the same biases in their story based on their knowledge, skills, abilities, education, and training. Explore what happened as a whole. Figure out their mindset to really understand them. This should be part of your goal of the conversation.

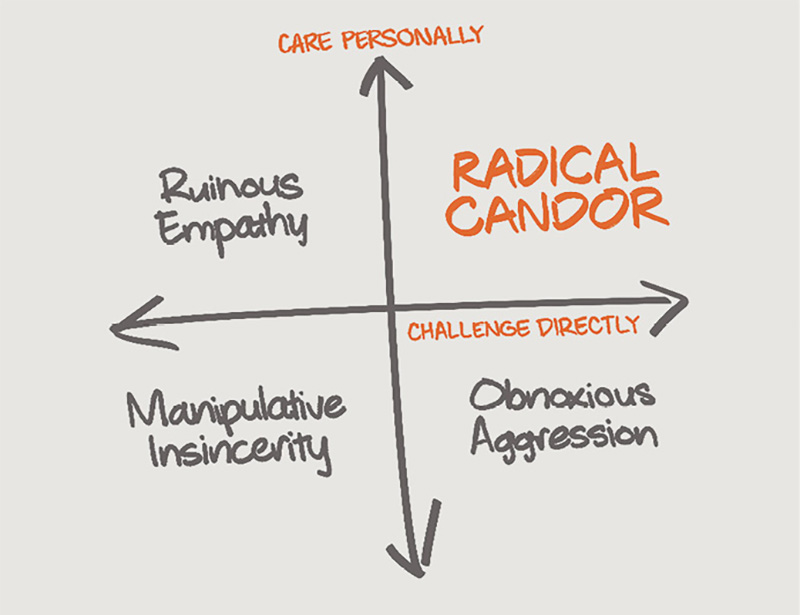

Figure 1. Kim Scott’s Radical Candor Boxes

(Scott, Radical candor: How to be a kickass boss without losing your humanity 2019). Used with expressed permission from Kim Scott and RadicalCandor.com.

Time for the Conversation: Radical Candor

If you haven’t read the books Radical Candor by Kim Scott and Crucial Conversations by Kerry Paterson and Joseph Grenny, both will help you tremendously with having this conversation.

Kim Scott’s Radical Candor goes in-depth on a two-by-two chart on how to have a difficult conversation. She refers to the vertical axis as the “give a damn” axis. As we mentioned before, you must care about them personally, and they need to know you are looking out for their best interest. We have been told to always be “professional” at work, but that doesn’t mean you can’t care about your people. Don’t be afraid to show them some love.

The horizontal axis is where you need to be direct. I would argue most firefighters want to know how you feel about the quality of their work. Be direct and let them know. They will not change if you sugarcoat their behaviors or, worse, never say anything to them at all. Being upfront doesn’t allow for any questions about where you stand. As Scott says in her book, “It’s not mean, it’s clear.”

It’s easy to think of bosses who fit into these categories and hang a name to the sections in Figure 1. But understand that Scott’s radical candor boxes aren’t personality tests. I have been in all four of these quadrants in my time as a supervisor, and if you haven’t yet, you will. Recognize where you are with each individual instance and work to be radically candid.

So, the top right of the box is where you want to be. You care about them, they know that, and you are being clear about the issue. So, what about the other boxes? If you don’t show you care but are direct in areas they need improvement, you are just being a jerk, and no one cares about what jerks think. Maybe you didn’t express enough of your intentions and how you care for them as your firefighters. You came across as a jerk and, more than likely, did not really get the persuasion for change that you hoped for.

The bottom left box is also a terrible place to be as a supervisor. That’s where the rumor mill or the backstabbing conversations go. You obviously don’t care enough about them to talk with them privately, and you aren’t saying anything to them about their inabilities or issues. Maybe you tell everyone else on your crew what terrible firefighters they are, hoping one of them will say something. When you slip into this box, you are being a weak leader.

Finally, the upper left box is probably where we slip into the most as supervisors. We constantly talk ourselves out of addressing issues because the crew is our friends. You want them to like you, so why say mean things? Maybe you say something but fill the conversation with their positive attributes so much that it sugarcoats your real message. We are taught this early on with the saying, “If you can’t say something nice, don’t say anything.” If you aren’t meeting their expectations as a supervisor, wouldn’t you want someone to tell you? As Scott mentions, be radically candid. “It’s not mean, it’s clear.”

Other Tips

Here are a few other tips for your conversation. Start with the facts. When you want to change a behavior, discuss the performance measures that can’t be contested first. “You did not check off your apparatus until eight hours into your shift.” “Our turnout time to get out the door averages nearly three minutes.” These are facts. Stay away from their personality traits and stick to the performance measures. “You are lazy” is no way to start a difficult conversation. Even if they are lazy, go after their performance, not their personality.

Embrace the discomfort as well. As you have more difficult conversations, you will become more comfortable with them, especially if you hold them correctly. You can tell them that you are uncomfortable with the conversation so they know where you stand. Maintain your directness. Stay in the top right box. Like Scott’s book says, “Be radically candid.”

Also, remember the discussion before about understanding their story and listening to understand. When you have this conversation, let them speak, and listen. Listen intently and ask questions that provoke thought. Depending on how skilled you are at thought-provoking questions, you may be able to allow them to talk themselves into seeing their deficiencies, all the while just sitting and listening.

After the Conversation

So, you’ve had the conversation. Now what?

Let’s say you have the conversation, and it goes well! Congratulations! The problem is that one conversation will rarely fix the issue. Especially if they are more senior personnel, you may be trying to change behaviors that have gone on for a long time. Give it time and constantly provide encouragement and feedback. There is a fine line between nagging and consistent reinforcement, so be careful.

Scott states that it’s best that these conversations are like the difference between brushing your teeth and getting a root canal. Giving two or three minutes regularly to reinforce your conversation is better than doing nothing and waiting for the cavity to need a root canal.

The other key to continuing the conversation is killing the rumor mill. As firefighters, we are like elephants. We don’t forget. We will remember when someone screws up and hang that on them for years to come. “You remember when Firefighter Bob screwed up on that call?” “Yeah,” you say. “That was ten years ago.” We are fallible. We will make mistakes. So will your firefighters. Have the conversation, then support them to their peers. Don’t let a simple mistake or poor action hang a label on them that they can’t escape. If you hear grumblings from people you’ve coached, specifically about an issue you’ve addressed, you don’t have to go into detail about the coaching session. Remind them that they have their faults, too, and they need to work on them. It may lead to your next difficult conversation.

You will know when you’ve arrived at the “difficult conversations” pinnacle when you have a firefighter, engineer, or new company officer pull you aside and discuss something you’ve been lacking. Remember, you must set clear expectations on when and how to have this conversation. If they follow that expectation and pull you aside at the appropriate time in an appropriate manner (respectfully), REWARD THEM! They are way outside of their comfort zone, coming to their supervisor with something that isn’t working for them. Provide positive reinforcement by showing appreciation for disagreeing with you or calling you out on something wrong. This takes a lot of humility and may be hard to listen to, depending on who it is. Just realize that they will never return with more feedback if you shoot them down for coming to you. If you don’t really mean “see something, say something,” stop saying it. If you do mean it, appreciate their radical candor.

The 360-Degree Evaluation

Often we have these conversations during evaluations. If your people are surprised by their evaluations or conversations during the evaluation process, you didn’t show up as a supervisor the other 364 days of the year. The formal evaluation process should not be a surprise. If so, find out how to better communicate with your crew.

A former HR chief and mentor informed me of issues he regularly saw. When they dealt with a serious performance issue involving the HR department, they came to the meeting with the disciplinary records and the employee’s last three evaluations. They read about some egregious behavior and then looked at three years of stellar evals. That’s when the entire table turned and look at the employee’s supervisor. Failing to address performance often backfires on the supervisor and eventually leads to poor results rather than the desired outcome.

If you aren’t familiar with 360-degree evaluations, this is a great method for becoming more approachable, increasing your supervisory skills, and having more impactful conversations with your crew. Be humble and honest about issues where maybe you didn’t provide the best leadership to address an issue. Encourage feedback from the firefighters or company officers who work for you.

The best way to encourage feedback is to follow their advice. Change! If they pull you aside and provide feedback and you follow their advice on serving them as a better leader, they are much more willing to continue having these conversations. This will only improve your ability to lead. If you consistently blow off their recommendations, they will stop providing them. Then, you lose that relationship and no longer have a mode to have meaningful conversations on behavior and actions that need to be addressed. When they see you as someone who can accept criticism, sharing that expectation is much easier. You can have a difficult conversation with them. They know your heart is in the right place.

Why They Are Called “Difficult”

Difficult conversations are just that—difficult. From a young age, our society has engrained in us to remain silent when, in fact, the best possible outcome is to say something directly. To accomplish this, we need to remember to stop and think before we act and speak.

Build a solid relationship where they know you have their best interest at heart. If we don’t have time to foster the relationship, remember that radical candor hinges on caring personally first. Ensure they know your intentions are pure, and remember, they probably didn’t mean to sabotage the department or your crew with their actions.

Remember that you must understand their story before you speak on yours. Listen with the intent to understand. There is a bias to every truth—biases on your part and biases on their part. Work through those and try to keep an open mind. Know that you, as a leader, in some way contributed to this issue. Recognize those flaws and embrace them prior to the conversation.

Once you have the talk, be radically candid. As Scott says, “It’s not mean, it’s clear.” Be direct, ensuring they know you care personally. Don’t be a jerk. Conversely, you may not have a clear message if you sugarcoat your conversation. Start the talk with facts and stay away from personality traits. Embrace the discomfort, and don’t think you can’t mention the various emotions you or they may be having.

After the talk, be prepared to have a “work in progress.” Change takes time. Take various opportunities to reaffirm good practices and remind them when they are slipping into old habits. A few minutes of small conversations regularly will keep things in a positive momentum. Shoot down any rumors or speak up for those you are trying to improve. Nothing is more discouraging than someone who will never forget a mistake and hold it over you forever.

Finally, reach the pinnacle with 360-degree evaluations and conversations. Encourage your firefighters or company officers to speak with you about your own flaws. Lay the framework early for these conversations through clear expectations. Reward them when these conversations happen, and effect change when needed.

With these tidbits, hopefully, you can better your crews and have a more open relationship that encourages dialogue as a path toward optimal performance.

References

Grenny, Joseph, et al. Crucial Conversations: Tools for Talking When Stakes Are High. McGraw Hill, 2022. bit.ly/3RosdkK.

Scott, Kim. Radical Candor: Be a Kick-Ass Boss Without Losing Your Humanity. St. Martin’s, 2017. bit.ly/45hUgb3.

Stone, Douglas, et al. Difficult Conversations: How to Discuss What Matters Most. Penguin, 2010. bit.ly/3x2Hn8m.

The Arbinger Institute. Leadership and Self-Deception: Getting Out of the Box. Berrett-Koehler Publishers, 2018. bit.ly/4ekgTQf.

John Russ is a 20-year fire service veteran and is a lieutenant/paramedic with the Brentwood (TN) Fire & Rescue Department. He has been the program manager for the International Association of Fire Chiefs Firefighter Near Miss Reporting System. He has worked with the HERO Registry Ancillary Committee to review research proposals for COVID-19 studies with healthcare professionals and conducted curriculum reviews for the National Fire Academy’s Safety Program. He also has been a member of the FDIC volunteer staff for nearly 20 years. He has worked for numerous career and volunteer fire and emergency service providers, including prehospital emergency medical service providers, specialized technical rescue organizations, and risk management and prevention entities. He has a master’s degree from Middle Tennessee State University in professional studies and two bachelor’s degrees from Eastern Kentucky University, one in fire and safety administration and one in prehospital emergency care.