Reports of gas leaks in residential occupancies have gone through the roof in the past few years. A gas leak explosion can cause total devastation to a residence, considering that a typical private dwelling that is 20 × 50 feet with eight-foot ceilings equals 8,000 cubic feet. According to Kyle’s Converter, that’s the same explosive force as two tons of TNT.

- Tactical Response to Explosive Gas Emergencies: Know Before You Go

- Natural Gas Emergency Strategy and Tactics

- Training for Natural Gas Emergencies

- Tactical Size-Up of Natural Gas Emergencies

Game-Changing Incidents

There have been three major incidents that occurred in the span of 2½ years in New York City that have led the Fire Department of New York (FDNY) to revamp its procedures relating to handling gas emergencies:

- March 13, 2014: A gas explosion leveled two five-story apartment buildings in the Harlem section of New York City, killing eight people, injuring at least 70, and displacing 100 families.

- March 26, 2015: A gas explosion occurred in the basement of a five-story tenement that eventually spread to and collapsed two buildings—the original fire building and exposure 2 (B); exposures 4D and 4A were completely destroyed by fire. Two were killed in this fire.

- September 27, 2016: A two-story Class 3 (ordinary construction) private dwelling with a flat roof and basement had a natural gas leak caused by a failure of the high-pressure gas service line inside the basement before the head of service valve. Responding units reported smelling gas from several blocks away as they approached the incident location.

The third incident was the proverbial “last straw.” The FDNY recognized the need to find a better solution to this growing problem, which prompted Deputy Assistant Chief John Buckheit to take on a project in the Fire Officers Management Institute to update the FDNY’s standard operating procedures in handling gas emergencies. Until this time, the only information the FDNY had was a gas emergency bulletin and a few WNYF articles.

First-responding firefighters carry the following two types of meters to deal with gas leaks:

- Meters that have a buzzer that lets firefighters know there is a gas leak (photo 1).

- Meters that alert firefighters by reading the percentage of the lower explosive limit (LEL)—for example, 80 = 4% atmosphere (photo 2).

(1) Photos by author.

(2)

More Incidents

Prior to the third incident above, Buckheit had his own experience with a gas emergency while working in the battalion. He was confronted with high readings in the basement of a four-story multiple dwelling. It was quickly determined that the leak was in the street and had migrated into the building. He had become extremely concerned when he had received reports from firefighters within the structure that the levels were 100% of the LEL (gas is explosive between 5% and 15% of the atmosphere).

Buckheit had immediately called for an emergency response from the local utility company. On arrival, the supervisor presented Buckheit with some very bad news: The pipes were more than 100 years old and were low pressure with no shutoff. The utility workers would have to dig up the street and plug the pipe; the backhoe was coming from Hackensack, New Jersey.

Buckheit had a serious dilemma on his hands—a building that was saturated with gas and no quick way to shut the gas. He evacuated the building and hoped for the best while keeping a keen eye on the readings.

It is extremely unnerving to have an occupied building loaded with explosive natural gas. I had two incidents within a few months of each other with the same crews working. The first was at approximately 1500 hours. We received a routine call for an odor of gas in the building. My initial thought was that someone left on a stove or a pilot light was out in one of the 30 apartments in the H-type building. Most of the time, it turns out to be a minor gas leak in the stove at the flex pipe in the rear. We try to shut the gas at the closest point to the leak, which is generally the butterfly valve in the rear of the stove (photo 3).

This complacent mindset changed as soon as we received a second source from the dispatchers advising us that the caller can hear the gas leaking out of the pipe. I immediately advised all units over the department radio to respond in on a full emergency mode.

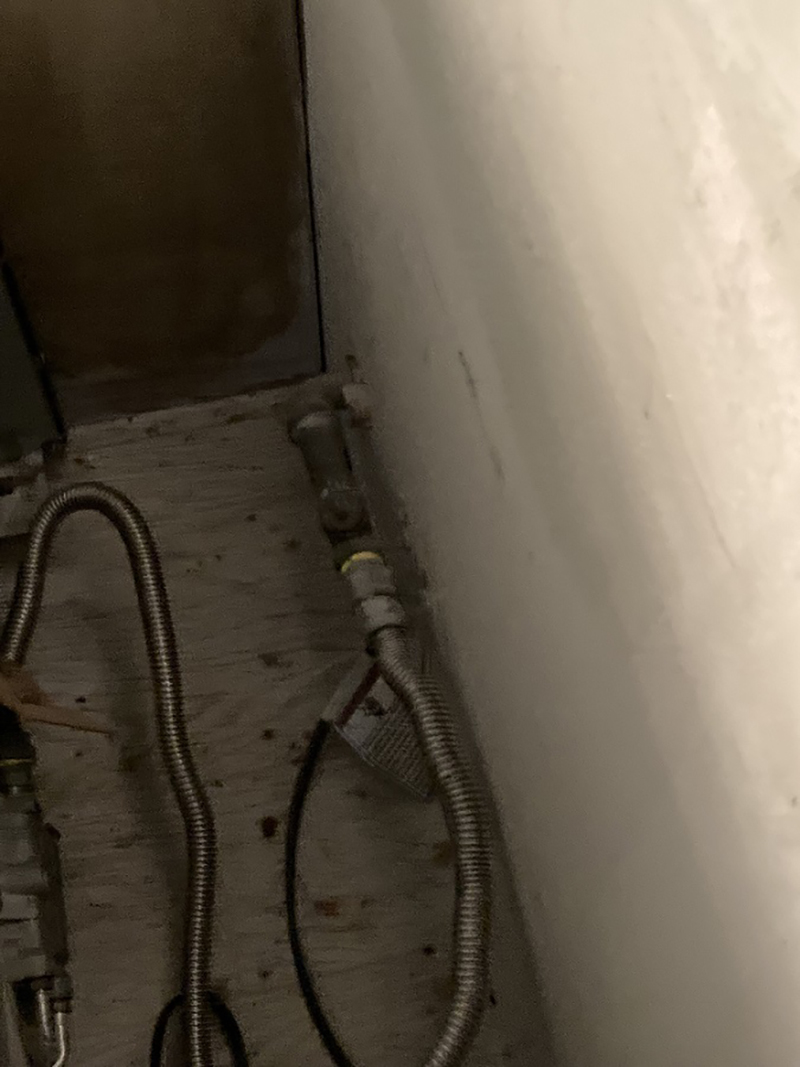

When the first ladder arrived on scene and entered the lobby, the lieutenant reported that the reading on his multigas meter was at 80% of the LEL (the FDNY treats 10% LEL as an immediate evacuation of the area). My worry was that, if it is 80% in the lobby, what will the readings be closer to the actual leak? I found the superintendent very quickly, and he advised us that he just replaced a stove in an apartment on the first floor. It turned out that the pipe in the wall broke in the process. We were able to shut the gas off at the next closest point in the basement at the meter valve that served that line (photo 4).

(3)

(4)

(5)

A few weeks later, we received a report of an odor of gas in a three-story Type 3 multiple dwelling on the third floor. Again, complacency set in; we go to so many of these calls that it is hard to not assume it will be just a minor leak. I was surprised when FDNY Lieutenant John Cassidy radioed me that he had 100% of the LEL on his multigas meter. The occupant had been an emotionally disturbed person and had turned on all the jets on the stove. He then barricaded the door while escaping out the rear fire escape. His intention was to obviously cause damage to the building. The lieutenant’s preparedness and quick actions averted a potential disaster.

Recently, we received a report of a manhole fire. On arrival, the first-due units discovered fire showing from a sewer grate (photo 5). The first-due engine began stretching a 1¾-inch hoseline to extinguish the fire.

I couldn’t figure out why a sewer was burning, so I walked over to the sewer grate to see what was happening. What I discovered didn’t seem right—the fire was coming through the cracks in the sidewall and in the street. It was apparent that we had a gas-fed fire. I ordered the engine to not extinguish the fire.

The companies on scene began checking for the possible source of the gas leak. Every manhole we checked gave us reports of high readings of both gas and carbon monoxide (CO). It appeared that the leak was all throughout the street. We decided to move all apparatus away from the suspected leak site—the “blast zone”—and evacuate a bakery that was in full operation as well as a fully occupied Amazon warehouse.

With so many manholes giving off high readings, it was difficult to define the parameters of the leak, but it was apparent that the situation was devolving rapidly. We needed the gas utility to respond immediately. Utility workers arrived shortly after the fire department and confirmed with their own meters that this was indeed a dire situation. No words were spoken, but I was able to determine the severity of the situation just by the look of concern on the face of the gas company supervisor. At one point, he had asked me if I felt any rumbling below the street surface; I had not.

I decided that this was the time to transmit a signal “10-75,” which would give us a full first-alarm assignment. I also requested a full hazmat response. Suddenly, a loud explosion occurred, followed by a 20-foot-high fireball, which shook nearby buildings. Three manhole covers popped as well. As a result of the explosion, CO and natural gas levels in the manholes dropped significantly. Flames intensified from the sewer and had now spread to the street itself.

Although we had an explosion and levels had dropped from the pent-up gases, we still had an expanding leak situation. Sectors were set up, and the next-in battalion chief was ordered to set up on the next avenue over and work with hazmat to check CO and gas levels in surrounding manholes and buildings. The hazmat battalion wound up taking over this sector.

The fire was directly in front of the bakery on the 1/2 (A/B) corner, where we were still getting high levels of natural gas and CO. The utility was still trying to find the shutoff for the gas. At first, the utility workers shut the low-pressure system. After that didn’t abate the situation, they shut the high-pressure gas line, causing an immediate drop in the flame height coming from the sewer, mitigating the situation. It was determined that the fire was a result of a manhole fire that migrated to the high-pressure main, causing a gas leak and fire.

Lessons Learned

Following are the lessons learned from these gas leak experiences.

- When gas-fed fires are discovered, do not extinguish them but rather let them burn and protect exposures.

- Call for your utility company immediately and attempt to determine which gas mains service the area and identify which main was affected.

- Call for hazmat immediately for metering to determine the extent of the leak.

- Establish a blast zone and ensure all units are kept outside, including the command post.

- Use additional battalion chiefs to sector large areas, and use hazmat, squad, and special operations command (SOC) ladders to continue metering all exposures and adjacent manholes. (Three hours after the manhole incident, there were 690 parts per million CO in one of the exposures.)

- Use the hazmat battalion as a group leader and have hazmat units, squads, and SOC ladders working in all sectors.

- Evacuate all occupancies in the blast zone.

- While investigating exposures during manhole fires/emergencies, carry the multigas meter. There have been several instances around the city where heat from an electrical conduit has melted plastic gas mains and caused leaks and explosions.

DANIEL P. SHERIDAN is a 36-year veteran of and a battalion chief with the Fire Department of New York (FDNY) assigned to Battalion 3. He is a national instructor II and a member of the FDNY Incident Management Team. Sheridan is also a lead instructor with Mutual Aid Training Group.