Excess Body Fat—Not Age—Viewed As Greater Culprit in Fitness Decline

and

A vast majority of the fire departments in the United States have maximum hiring ages, usually around 35 years. There exists a growing concern among administrative personnel as to the validity of such age restrictions, particularly in light of the Age Discrimination Employment Act.

The purpose of this article is to discuss our laboratory findings and relate them to what we know about the necessary fitness requirements of fire suppression.

Our initial attitude regarding aging led us to believe that there was a cause and effect relationship between aging and regression of performance. After all, it’s one of those things that “everybody knows.” In our earlier research efforts, we noticed that there was a steady decrement in fire task performance with increasing age.

However, we also knew that there was a significant amount of variability within each age fitness classification.

We had even mentioned the fact that quite a number of older fire fighters could outperform individuals 20 years their junior. What we needed was concrete data to provide answers to the lingering questions: (1) What are the true effects of aging? and (2) what are the controllable effects?

Test methods

Let us examine the testing methods. A battery of physical fitness tests was administered to all the fire fighters of a large metropolitan area fire department. Over 600 fire fighters were assessed on a battery of physical fitness tests which included all those items deemed indicative to effective fire suppression.

The laboratory evaluation included tests designed to determine cardiovascular fitness and muscular fitness assessment as well as a number of health indicators. A complete test description follows.

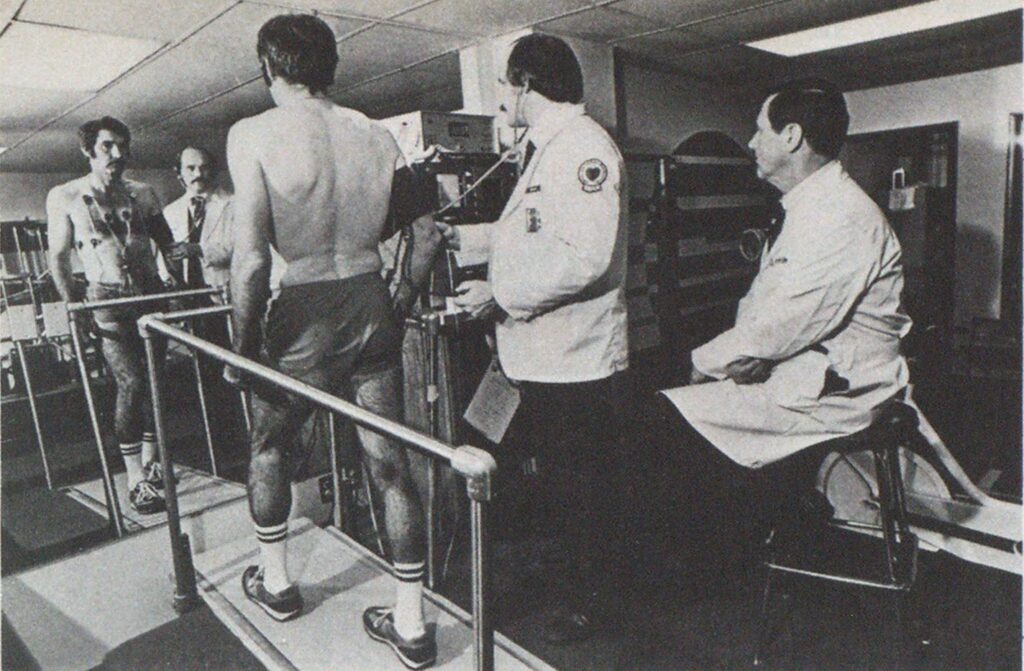

Aerobic fitness was determined via the administration of a Bruce protocol on a motor-driven treadmill. Each fire fighter walked on the treadmill belt, without holding on, until he reached a symptom-limited maximum end point. The end point was defined as that point where they could no longer continue due to fatigue. The limiting factor in staying on the treadmill is the amount of oxygen that the body can provide to allow for the ever-increasing workloads. Time for this test was reported in minutes and tenths of minutes.

Testing for muscular fitness was accomplished via the use of some familiar endurance test items, such as bent-leg sit-ups in two minutes and push-ups to exhaustion. Determinations of static strength used dynomometers for hand or grip strength and shoulder/upper body strength. Muscular power was determined through the administration of a standing broad-jump test, while flexibility of the hamstring group was evaluated via a sit-and-reach test.

Fat weight determined

Since body fat has been repeatedly shown to be important in physical performance, measurements were made by use of the hydrostatic, or underwater, weighing technique. We corrected for the air trapped in the lungs by measuring the residual volume and making the appropriate corrections in the underwater weight. The total fat weight, as well as the percent fat, for each fire fighter was recorded.

Additionally, we reviewed all the EKGs, medical history questionnaires and blood profiles. Since a discussion of all the results is too voluminous, we will confine our discussion to those items which are of a performance nature only.

The general and descriptive statistics of the group are displayed in Table 1. On the basis of the means, we would say that the group has the characteristics of an average fit population.

Table 2 shows the distribution of the department by age. The average age is 30.309. A standard deviation of approximately seven years indicates that 67 percent of all department members lie within plus or minus seven years of being 30.4. As you can see from Table 2, there are only five individuals over the age of 50 in this sample.

After performing statistical procedures to produce the descriptive data, we investigated the relationships between age and performance. A simple correlation coefficient was generated for each pair of comparisons. A correlation coefficient expresses the strength of association between two variables. For example, rainfall and grass height would be positively correlated. If there was a perfect correlation between the two variables, the correlation coefficient would be 1.0. A nonexistent relationship between two variables would be 0.0. Usually, correlation coefficients of .2 to .3 express only moderate relationships.

Variables may also be negatively correlated. For example, consider correlations between aerobic fitness and elapsed time on some running event. As aerobic fitness goes up, the time to complete a 2-mile run goes down. Since there exists very few perfect correlations, or probably none that we can effectively measure, a correlation of .9 is a very strong correlation. Scores in the range of ±.7 are generally reliable indicators of association. Scores in the area of ±.4 explain a small part of the relationships between two variables.

If you square the correlation coefficient, you can determine the percent of variance contributed by one variable on the other. For example, a correlation of .5 squared is 25 percent, or 25 percent of the variance is explained by the effect of one variable on the other.

Let’s see how this looks upon first examination. Table 3 shows the interrelationships between age fat, and a number of physical fitness indicators. We can see that many, if not most, of these correlations are statistically significant, and strongly so.

Tables 4, 5 and 6 display unadjusted means for each of the five-year groups. We have gathered the variables into anthropometric, neuromuscular and cardiovascular (aerobic) data.

From all of these data, one would believe that with an increase in age, there is a loss in performance. It is particularly true, but there is something else operating besides age that is impacting on performance. Examine the relationship between age and percent fat. As we can see in Table 3, there is indeed a very strong correlation between these two entities.

However, what we know about body fat leads us to believe that body fat may be a culprit in this regression of performance. One sure tip-off is the examination of the relationships between strength and age. Static strength is impacted only by the amount of lean (fat free) muscle mass.

Since Table 5 shows that the amount of lean mass remains constant across the department at any given age, we see that there is no difference in strength by any of the age groups examined. It is also known that strength is an important component of physical fitness and fire fighting.

In other words, when examining the age-strength relationship, there exists no significant difference among the age groups. Body fat does not affect performance in this test because it is static in nature. But when we examine the relationships between those dynamic tests, such as push-ups and treadmill time, we notice that the correlation coefficients are almost identical to those expressing the relationships between age and performance. So the question that now needs to be answered is, what is affecting the loss in performance? Is it age or is it becoming fatter? And what impact does body fat have on overall performance?

Finding the answer

A statistical procedure known as analysis of covariance allows us to answer that question. Covariance allows us to remove, or hold constant, a certain characteristic while examining the relationship between a second and a third variable. By performing an analysis of covariance for each of the physical performance characteristics, we can adjust the scores so as to display what they would be if body fat were at an approximate level. This data is shown in Figures 1,2 and 3. As you can see, once we remove the effect of carrying extra body fat, the differences among groups are reduced significantly.

Excess body fat has no advantage. It has the same debilitating effect on performance as does the carrying of unnecessarily heavy equipment. For years, we have been concerned about the weight of protective equipment. Yet, that aspect of performance that we can readily control—our body fat levels— has not received the same amount of attention.

Since the storing of body fat is a reversible condition, then the debilitating effects of obesity can be reversed. On the basis of this data, it appears clear that every department should be charged with the responsibility of a body fat control program. The maintenance of a fire fighting force is every bit as important as apparatus maintenance.