EMS Response to the Explosion

The detonation of the terrorists’ bomb under the World Trade Center (WTC) complex on February 26, 1993, created the largest technological disaster New York City had ever experienced. The bombing also initiated the most significant emergency medical service (EMS) response in the city’s history.

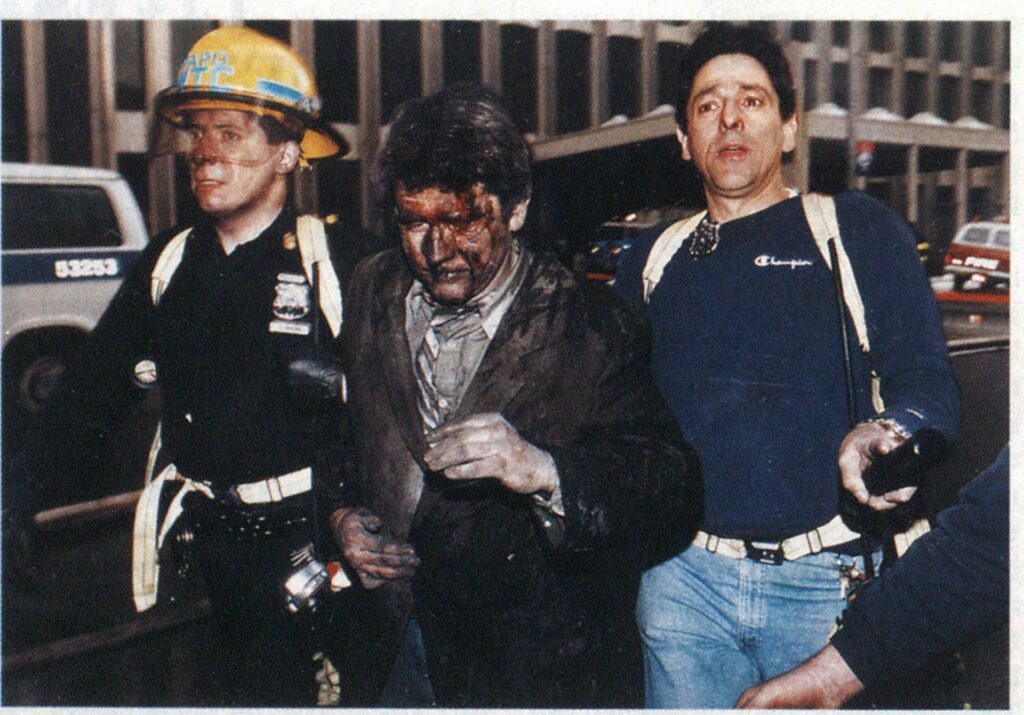

(Photo by David Burns/Phototrends.)

NYOEMS

The New York City Emergency Medical Service (NYOEMS) is a thirdservice public safety and health care agency whose mission includes the provision of prehospital emergency medical care and transportation throughout the five boroughs. NYOEMS operates the 911 communications and control center responsible for coordinating the response of municipal, hospital-based, and mutual-aid resources to medical emergencies and is the municipal agency responsible for coordinating and directing prehospital care resources and operations during a disaster.

Responding to more than 2,800 requests for service daily from 16 ambulance stations citywide, NYOEMS operates some 220 ambulances on the day shift. Field supervision is structured through a uniformed chain of command. Each station is commanded by a deputy chief, who is responsible for EMS operations within the district served by that station. Each station has a captain serving as executive officer and fields one or more patrol supervisors (lieutenants) on each shift. Patrol supervisors’ responsibilities include all field activities within their response areas, with special emphasis on immediate, proactive response to multiple casualty incidents (MCIs) or unusual events.

DISASTER PREPAREDNESS

NYC*EMS responds to several MCIs daily. Our Emergency Medical Action (disaster) Plan is activated when an incident produces more than five patients or exceeds the capabilities of a two-ambulance response. NYC*EMS has used the incident command system (ICS) since 1982; it is used during all MCI operations and unusual events.

An MCI preplan program is in place; its goal is to identify and develop response plans for MCIs at locations with above-average potential for their occurrence, such as transportation hubs, high-occupancy locations, and hazardous-materials storage sites. The plans consider the best approach routes, staging locations, command posts, special hazards, obstructive characteristics, and resources available on site. Plan data are carried by supervisors on patrol and maintained in the communications center for transmittal to field units. The WTC preplan has been in existence since 1985 and had been exercised on a regular basis through routine incident responses to the complex.

INITIAL RESPONSE

Immediately following the WTC bomb’s detonation, first calls to 911 reported an explosion and many injuries. Our earliest notice came seconds before, when our communications center monitored FDNY Engine 10 (quartered around the corner on Liberty Street), which reported the blast and transmitted a signal for a working fire.

Preliminary reports indicated that an electrical transformer had exploded under the Vista Hotel, located in the WTC complex. A transformer explosion is not a particularly unusual event in a high-rise building. Based on our experience with such events, our primary concern was potential polychlorinated biphenyl (PCB) contamination from transformer oil.

The initial EMS assignment to the WTC was one basic life support (BLS) unit and a patrol supervisor. The assignment was upgraded to an MCI signal within three minutes, based on additional calls to 911 Three additional BLS units, one advanced life support (ALS) unit, three patrol supervisors, one chief officer, one major emergency response vehicle (MERV), and two squads were assigned by 1223 hours.

(Photos by Alan Saly/courtesy EMS Local 2507.)

(Photos by Alan Saly/courtesy EMS Local 2507.)

The first-arriving ambulance encountered several patients in serious condition and began triage. The crew later reported a “feeling of impending doom” as the wounded surrounded them. The first-arriving officer was at the scene within five minutes. He assumed command and initiated the ICS.

In sizing up the incident, still thought to be a transformer explosion, he determined that the preplanned staging area was not wellsituated to serve the needs created by this incident. He established a staging area remote from the preplanned location and directed the initial crew to transport two critical red-tag patients, who had been in a car at the entrance to the parking garage when the force of the blast hit them. Actions such as this one were instrumental in restricting the loss of life to those lost in the immediate blast.

Additional responding units arrived and encountered patients everywhere, as people fled the buildings or were removed to fresh air. Responders were overwhelmed by the number of patients brought to them. Crowds of patients exited the buildings; others were simply lying in the street, exhausted and overcome. The first-arriving officer emphasized that triage was critical to the operation’s effectiveness, as it enabled him to allocate resources and make quick, logical transport decisions.

CASUALTIES

A small number of the patients had sustained major multiple trauma and burns from the blast effect. Most of the patients emerged from the building with classic “soot masks” on their faces and were suffering from smoke inhalation. There were many cases of minor trauma, including injuries sustained from falling glass and debris or while rapidly evacuating via darkened stairways in extremely crowded conditions.

In addition to trauma, many people suffered exhaustion as a result of walking down from the upper floors. Preexisting medical conditions, especially asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, cardiac disease, and hypertension, were aggravated. In other instances, medical difficulties were associated with pregnancy.

EMS URBAN SEARCH AND RESCUE

Victims disentangled from the debris and rubble in the parking garage area were brought out to waiting EMS triage teams. While the fire and police departments conducted search and rescue, the NYC*EMS Urban Search and Rescue Team was activated. This team is the medical component of the FEMA-sponsored New York City Urban Search and Rescue Task Force. The Task Force, consisting of members of the City of New York (NY) Fire Department, New York City Police Department, and New York City EMS, is one of the 25 teams ready for deployment to domestic disasters when multiple structural collapses have overwhelmed the local resources. The medical team, consisting of paramedics and supervisors, remained on the scene for 23 days after the initial incident to provide medical support to the large number of lawenforcement investigators and demolition crews operating below ground at the blast site. During this phase of the operation, NYC*EMS treated an additional 90 victims.

NYOEMS INCIDENT COMMAND STRUCTURE WORLD TRADE CENTER BOMBING

HELICOPTER MEDEVACS

Among the scores of people who tied to the roofs of the towers, 28 with medical problems were airlifted by New York City police helicopters and brought to a landing zone adjacent to the EMS staging area. The landing zone was sectored as an EMS operational unit to allow for victim triage, stabilization, and transport. Victims were removed to medical facilities through the staging area.

Some controversy relating to the safety and operational benefits of helicopters has resulted in the fire and police departments’ reviewing helicopter operations at high-rise emergencies.

COMMAND AND CONTROL

As previously noted, ICS has been used by NYC*EMS to manage mass casualty incidents since 1982. Over the years, the NYC*EMS ICS. derived from other nationally recognized incident management systems and modified for medical disaster operations, has been employed at hundreds of disasters and MCIs—including preplanned events such as rock concerts and the annual 26-mile New York CityMarathon. Although some of these responses required the on-site evolution of an extensive ICS model, none were as detailed and complex as the ICS structure developed for the WTC response.

Due to the scale and complexities of New York City, the often vast scope of the emergencies that occur, and the size of the city’s agencies, a unified command structure is used. Agencies command their own tactical efforts at the operational level, while interagency strategy development and activities occur at the command/ senior management level. At this disaster, the city’s Office of Emergency Management established a strategicinteragency command post. Senior managers from all agencies and disciplines were brought together to make policy and create a commonality of objectives throughout the operation.

The NYC*EMS ICS, which is modular in design, is structured to allow it to be readily integrated with the unified interagency command structure at any type of emergency. This approach facilitates responses to everyday emergencies and major events, making them smooth and effective.

Taking a top-down approach, geographic and functional management units—sectors and divisions—were implemented as needed to meet the rapidly evolving and expanding situation. From a tactical command post located aboard the NYC*EMS Field Communications Unit, the EMS incident commander, a deputy chief from the Special Operations Division, unfolded an ambitious command structure to satisfy the obligations of patient care and provider control needs to ensure an efficient EMS response. Serving as senior advisor, the EMS chief of operations remained at the command post to oversee the incident’s management.

Dozens of divisions and sectors were deployed to meet geographic and functional objectives. Thousands of people, hundreds of whom required medical intervention, were evacuating from countless exits throughout the 16-acre complex. In addition to conducting triage and treatment at these locations, issues such as communications, safety, and medical equipment logistical support needed to be addressed.

Divisions, established with all the necessary sectors to satisfy their specific requirements, were set up at Tower 1 (1 World Trade Center), Tower 2(2 World Trade Center), the Vista Hotel (3 World Trade Center). 5 World Trade Center (a nine-story office building), and the Winter Garden atrium. Each division was headed by a division commander who reported directly to EMS command.

EMS command itself was a tremendous undertaking. The EMS incident commander’s immediate staff was managed by a deputy chief from the Manhattan Division, who also served as the communications officer. Other command staff positions included those of interagency liaison, publicinformation officer, and mutual-aid coordinator and planning.

Although strategies were developed at the command level, independent strategy development was necessary at the division level as well. While tactics essentially were similar at each division, the scope and magnitude of the problems in each building were different. The basic objectives of each division were to collect, triage, treat, and transport the victims. Because the operation was spread over such a large area, no single strategic or tactical effort could be employed uniformly throughout the divisions. Independent thought, coupled with intense interdivision coordination and communication, was necessary to ensure that each division was functioning in a harmonious manner.

TRIAGE

Triage was performed utilizing the Simple Triage and Rapid Treatment (START) system, which employs an extremely rapid clinical evaluation algorithm for patient evaluation and categorization into one of the four classic categories. All triaged victims were tagged using METTAGs, enabling us to track their condition and to avoid the need for multiple redundant assessments as the patients were moved.

Each of the geographic triage sectors was established in a location where a steady flow of building evacuees was passing through a natural funnel or choke point, such as the building exit. Since all did not require EMS services, touch-triage assessment was used. Touch triage, which has been used for years at major annual events such as the New York CityMarathon, involves closely monitoring, but not interfering with, the egressing group by EMS personnel assigned to triage. When a person appearing to require assistance or EMS services is identified, the EMT makes contact with the person; performs a rapid assessment; and, if appropriate, removes the victim from the flow of evacuees into the triage area, where triage is completed. In this way, a large number of rapidly moving people can be assessed quickly without impeding the flow’ of egress.

As the buildings became tenable and the flow of evacuees lessened, forward triage sectors were established in the building lobbies and, ultimately, on the upper floors of the tower buildings. These forward triage sectors enabled EMS teams to respond quickly to reports of casualties on the upper floors and ultimately evolved into casualty collection points (CCPs).

CASUALTY COLLECTION POINTS

The initial CCP was established very quickly following EMS arrival at the complex. An officer assigned to reconnaissance saw that many evacuees were leaving the complex in apparent distress, without their coats, in the snow and 20-degree temperature. As he investigated where they were going, he noted their migration to the Winter Garden, an enclosed atrium and food court in the World Financial Center across the street. On entering the Winter Garden, he observed a large crowd of people requiring medical assistance. This operation naturally evolved into the Winter Garden Division.

Additional CCPs were established in the lobbies of nearby buildings and on commandeered transit buses in the surrounding streets. The forward triage areas on the upper floors of the towers gradually evolved into CCPs, as victims on the upper floors were gathered there to receive care and await emergency evacuation down the stairs or the restoration of powder for elevator egress.

TREATMENT

In the CCPs, paramedics and EMTs primarily administered oxygen, assessed patients, and gave psychological first aid. Most patients did well with this supportive therapy, but some required ALS care, including cardiac monitoring, intravenous line placement, and parenteral medication. When critical patients were detected through the triage process, where evacuation was possible, they were treated and transported rapidly to area hospitals. In several cases, critical patients were treated for extended periods of time on the upper levels of the towers until the logistics of their evacuation could be put into place.

Ordinarily, NYC*EMS paramedics utilize standing orders to provide initial ALS care and then are required to contact the EMS Telemetry Control Center physician for clearance to implement medical-control options. At this incident, the EMS medical director authorized the implementation of all medical-control options as standing orders, eliminating the need for telemetry contact and streamlining patient care in many cases.

Similar issues arose with those paramedics who responded from New Jersey on mutual aid. With the authorization of a New York State Department of Health representative at the scene, the New Jersey resources were permitted to utilize their standing orders and communicate with their own medical control in New Jersey, allowing them to provide a full spectrum of ALS care without burdening the New York City system.

TRANSPORT

Patients requiring hospital care were transported to one of 17 hospitals in three boroughs. To minimize radio congestion, each division was directed to make its own hospital selections. Although this was potentially problematic, the geographic layout of the scene facilitated each division’s routing of patients in a different direction from the incident, avoiding a major impact on the hospitals in all but two cases.

Initial transport resources included police cars and buses as well as school vehicles that were waiting for several visiting kindergarten classes whose children were trapped in the south tower. Many of the early-arriving ambulances were dead lined in the staging area, as their crews were put to work inside the complex. Ultimately, mutual-aid ambulances performed many of the transports to hospitals, enabling NYC*EMS members to continue operating at the scene.

HOSPITALS

Immediately following an assessment of the situation at the WTC, all of the New York City 91 1 systemreceiving hospitals were notified by the EMS communications center to anticipate incoming casualties. Many activated their external disaster plans, holding over their day shift staff, clearing emergency departments and operating rooms, and bringing in additional personnel and supplies.

While some victim self-referral to area hospitals was anticipated, the volume of walk-in cases from this incident was staggering. The “selfreferral phenomenon” was particularly evident at New York Downtown Hospital, located several blocks from the complex, which ultimately received almost 200 patients over 13 hours—many of whom were not transported by ambulance.

Several hours into the incident, as the extent of the self-referral phenomenon became apparent, NYC* EMS officers and police officers were dispatched to every hospital in the city and the surrounding counties to account for and track additional victims. Many of these people had left the complex following the emergency, made their way home, and began to feel symptomatic as their adrenaline wore off. In all, some 411 patients were identified as having arrived at hospitals in all five boroughs and the outlying suburbs through alternate means.

PATIENT TRACKING

Experience has shown that the best way to track patients at a disaster scene is by name, which enables emergency personnel to definitively ascertain the disposition of individuals and to determine which people remain unaccounted for. Under normal MCI procedures, this is done at the scene by NYC*EMS.

At this incident, however, the sheer volume of patients precluded the use of name tracking, although it was attempted at the beginning. Accurate number tracking was done from the scene, and all ambulance crews were directed to call their patients’ names into the communications center following their transport to a hospital.

COMMUNICATIONS

Communications at the scene were coordinated through the NYC*EMS Field Communications Unit. A second field communications unit, provided by Ridgefield Park, New Jersey, served as the coordination point for the EMS mutual-aid response.

Early communications were hampered by the partial loss of cellular telephone and pager service in the area when power was shut down in the WTC complex and rooftop antennas were disconnected to allow helicopter operations on the tower roofs.

Many 911 calls were received from callers trapped in the towers who had access to cellular phones. Communications center operators stayed on the line to calm and advise these callers, and their information subsequently was relayed to the command post to assist in the search and evacuation processes.

Two types of radio networks were used for on-scene communications. A command network between the incident commander and command post and the geographic division commanders, functional sector officers, and command staff made it possible to coordinate activities at the strategic level.

On a tactical level, individual tactical networks were employed to facilitate communications between the division commanders and tactical operations posts, geographic sector officers, task force leaders, and division staff. Face-to-face communications and runners also were used effectively within the divisions.

The Field Communications Unit maintained contact with the communications center and coordinated the information flow by monitoring radio traffic on the incident ground networks. Periodic progress reports were compiled there and broadcast from the scene.

EMS MUTUAL AID

Although there was no precedent for mutual aid coming into New York City, mutual aid was monumental and contributed heavily to the success of the medical operation. Through informal mutual-aid plans, NYC*EMS has participated in mutual-aid exercises and has sent resources to assist neighboring communities but has never had an occasion to require it In addition to the contribution mutualaid resources made to the disaster effort, mutual aid at the incident scene ensured uninterrupted 91 1 coverage to the unaffected communities of New York City. On February 26. 1993, the day of this disaster, NYC*EMS received 3,015 requests for EMS service unrelated to the disaster. The WTC bombing was just one of 3,000 incidents handled that day.

EMS commanders from New Jersey remained at the mutual-aid command post (located adjacent to the EMS command post in the command post area) and proved to be invaluable in the execution of this effort. When the dust settled and the smoke cleared, we determined that the state of New Jersey had committed 52 EMS agencies, sending a total of 69 EMS units into Manhattan to assist.

In addition to the mutual aid received from the state of New Jersey, mutual aid came from 12 community volunteer ambulance corps from w ithin the city. These units, some of whom have formal mutual-aid agreements with NYC*EMS, are not routinely part of the 91 l system. They provide service within well-defined community boundaries—but on February 26, they saw no boundaries.

Mutual aid also was provided by 12 of the city’s commercial ambulance providers, which sent 49 ambulances. Commercial ambulances in New York City handle private EMS contracts and have the market on hospital-to-hospital transfers but do not operate within the 911 system.

(Photo by Robert Knobloch.)

PLANNING

Planning and administration tasks were assigned to a planning sector. At the command staff level, the planning sector officer reported direct!) to the IMS incident commander. The team consisted of chief officers, line officers, and staff personnel. The sector’s responsibilities included developing plans for the deescalation of the large number of resources present and operating; rest and rehabilitation, which included critical incident stress debriefing (CIS!)) and crew rotations; and commencing data collection for the post incident report.

Experience has shown that it is important to thoroughly document the response effort. This serves three principal objectives, maintaining a historical reference document for critique, research, and legal purposes; providing information to law enforcement investigative agencies—in this case local, state, and federal; and documenting expenses incurred for the response. Included in the postincident report were a detailed breakdown of the command structure; a compilation of resources, both human and logistical; and victim tallies, including their dispositions.

LOGISTICS

NYC*EMS maintains six logistical support units (LSUs). These trucks are strategically located throughout the city and serve as mobile medical equipment caches. All of them were deployed to the scene and supplied the divisions with medical hardware and software as requested. Under the control of a captain serving as the logistics sector officer, the LSUs were instrumental in ensuring adequate supplies, especially portable oxygen tanks, as well as oxygen delivery devices anti systems.

MEDIA RELATIONS

Hie dissemination of public information was done from the command post by a team of public information officers (PIOs). Public information was a monumental and difficult task because most sound bites were live and because of constant changes and updates in information due to the rapidly evolving situation.

In addition to the on-scene release of information, a PIO remained at EMS headquarters answering telephones and providing on-air commentary. This was significant in providing accurate information to WCBS-TV, the single remaining on-air television station in the greater New York area (all other stations with transmitters atop the WTC were knocked off the air when the power was lost) and is believed to have contributed to lower 911 call volume in the uninvolved communities of the city.

EMS EMERGENCY OPERATIONS CENTER

We learned from past experiences, such as the two recent USAir crashes in New York and a major subway disaster, that an intraagency emergency operations center (EOC) is of tremendous benefit. The EMS EOC] served as a focal point where agencyspecific needs were addressed behind the scenes. The EOC staff functioned as a direct medium betw een the EMS operations and support services bureaus, shortening the lines of communication. This was necessary to monitor the situation in the other areas of the city; to take action to satisfy incident logistical demands; and to handle administrative duties, thereby freeing field commanders to focus on medical operations. The EOC, located at EMS headquarters, maintained direct communication with the EMS command post and was managed by the deputy chief of operations.

REHABILITATION

The EMS commanders were very conscious of the need to monitor personnel for critical incident stress during this incident. Efforts were made to limit any individual’s exposure to gory or bizarre scenes. A rehabilitation sector was established, and transit buses or other facilities were designated at each division as locations at which members could rest between assignments. Through the assistance of the American Red Cross, Salvation Army, American Express Company, and others, refreshments and full hot meals were provided to the personnel.

Early on. the NYC*EMS CISD team was activated and responded to the scene. Informal sector demobilization assessments were conducted during operations and by the officers when sectors were secured. On-site evaluations and assistance were provided by peer team members and professional staff.

Within a week following the bombing, the CISD team had conducted formal debriefing sessions for officers, municipal EMS providers, hospitalbased personnel, and the various mutual-aid responders.

LESSONS LEARNED

The EMS response to this extraordinary incident, the most significant disaster in the history of the service, was on a massive scale. The scope and complexity of the response presented exceptional challenges to veteran emergency response personnel, who responded in kind with exceptional commitment. The successful outcome of the response, as well as the limited loss of life, is a testament to the extraordinary efforts and effective coordination of all those who responded.

EMS and fire services must plan and prepare for these eventualities. Keep in mind that terrorism is not isolated to urban centers. Firefighters and EMS providers in rural and suburban areas must be prepared as well. Readiness is the key to success. Planning will help to ensure that your fire department and EMS system respond in the safest and most efficient manner possible.

Through the use of a well-exercised ICS; written and practiced operational and mutual-aid plans; site-specific plans for sensitive locations such as shopping malls, sports arenas, and transportation hubs; and plans for massive casualty distribution, the impact of a terrorist event on any community and its emergency response forces will be significantly reduced.

The terrorist bombing of the World Trade Center has illustrated that we must anticipate a worst-case scenario in our communities. We must make all efforts to be prepared to respond to these incidents in the most efficient and safest manner possible.

Many lessons were learned and reinforced in the aftermath of this incident. They have value for large and small communities, as we have seen that terrorism can strike anytime, anywhere. This was further exemplified by the recent investigation and arrest of members of an alleged terrorist plot to carry out a massive day of terror in New York City. Some lessons follow.

- The need for a medical incident command system cannot be overstated. Span of control is critical to maintaining the ability to manage; no manager should have anything but a reasonable reporting relationship, with 1:5 being optimal. This arrangement enhances operational efficiency and communications and reduces the burden of information and responsibility overload.

- A command team concept, with deputy incident commanders and a well-trained command post staff, can assist in executing operations, as well as in receiving information.

- If you expect your personnel to do something in an emergency, be sure they are accustomed to doing it routinely, especially in the case of incident command. Therefore, use it at all routine incidents.

- Consider implementing a “management liaison” at the command staff

- level to brief and interact with senior management and political leaders. This will allow the incident commander to focus on operations.

- In the World Trade Center incident, both the medical and fire operations were extensive enough to require intense management. Fire departments that have emergency medical service (EMS) responsibility should closely examine their medical disaster management procedures to ensure their ability to manage both major elements simultaneously.

- Clearly delineating duties, especially at a major incident, is critical to ensuring that all responders know their roles.

- Consider the need for multiple staging areas to ensure the best access to multiple sides of an incident. Consider the routes vehicles will use to return to the scene.

- At major incidents to which numerous vehicles will respond, categorize the vehicles by type. Separating basic life support ambulances, advanced life support ambulances, specialty units, and support vehicles w ill make it easier to deploy them.

- Major incidents, or those that produce multiple patients over an extended period of time, necessitate making decisions regarding transporting truly critical patients before the end of the triage process. These patients may deteriorate rapidly or expire if they are not managed aggressively from the outset. These decisions, however, must be balanced against the resources available.

- Triage tags really work —use them regularly.

- As we learn more about the ill effects of entrapment and compression on the human anatomy, it is clear that crush syndrome must be addressed while rescue and disentanglement is underway. Crush syndrome (trauma to muscle tissue that can cause shock and renal failure) can debilitate or kill victims if they are not treated by specially trained medical personnel before being removed from their entrapment site. Paramedics are well-equipped to deal w ith the effects of crush syndrome and must be in-

- eluded in any urban search and rescue effort.

- The issue of medical control should be considered and included in the mutual-aid plan. Do not leave this area for speculation. Allow mutual-aid providers to use their own protocols and medical control when possible. Disaster medical control protocols are recommended so that the need for physician contact is eliminated during a disaster.

- Transport decisions should be made on an incidentwide basis—not by individual divisions.

- EMS personnel should be trained in landing zone operations and safety. Safety is critical when operating around helicopters All personnel, especially the landing zone sector officer. must observe hazards.

- Despite pressure to track every victim, name tracking at the scene may not he feasible. Include a strategy for acquiring victim pedigrees in the disaster plan; consider incorporating the use of law enforcement personnel or volunteers.

- There is no way that fire/rescue and medical communications could have been conducted within a single tactical network. Traffic overload would have severely interfered with the efficiency and safety of operations.

- Division progress reports to command are vital.

- EMT trainees from our Division of Training formed a staircase-relay mechanism. These teams were placed every two to three floors from the lobby to forward triage areas and casualty collection points on the upper floors. They were used to move equipment up and patients down without exhausting individuals who would otherwise have to do multifloor carries.

- All portable radios must be able to function on designated tactical networks.

- Dynamic redeployment plans are needed to backfill area units drawn into an incident.

- Preplan alternative procedures for situations when your infrastructure (communications systems, cell

- phones, and pagers, for example) fail secondary to the incident.

- Consider the need for additional staff at the communications center.

- Develop mechanisms for disseminating information to hospitals rapidly and continuously. One approach would be to include radio links monitored by hospital staff for broadcast updates (also voice alarm or voice pager system). A computer link in medical facilities and telephones with automatic speed dialers with messaging and acknowledgment features would aid in this process. Hospitalnotification problems that must be addressed include the following: calling several hospitals at a time, providing informational updates, notifying hospitals when the alert is concluded, and controlling patient flow. Hospitals must provide feedback to the communications center: “We can handle everything” vs. “We’re drowning in patients” vs. “You didn’t send us enough.”

- Never underestimate the need for mutual aid —even in large cities.

- Joint training and exercises in

- MCI operations and incident command are required for mutual-aid responders.

- Mutual-aid plans addressing activation and lines of authority must be formalized.

- Mutual-aid resources left in staging and not used will be frustrated. Crews should be debriefed and given an understanding of the incident and their essential role of standing by in reserve.

- Mutual-aid plans not only should cover the response to a disaster but also should provide for continued emergency service coverage to unaffected communities.

- Common mutual-aid frequencies would have been beneficial.

- Plans for managing ongoing routine 911 operations, such as holding over shifts, as well as for managing the incident, are needed.

- Documenting the response is critical in cases where federal disaster declarations are likely.

- Plans to control and reduce equipment loss and conduct equipment recovery are needed.

- Advance agreements with vendors to replenish oxygen supplies at the scene or to stay open at a local site so that bottles can be refilled as needed could be beneficial.

- Multilators, devices that deliver

- oxygen to multiple patients, are great and are available commercially.

- Being self-sufficient through measures such as bringing power and lighting to the scene, will allow EMS objectives to be met without depleting other agency resources.

- If you have a reserve ambulance fleet, spare equipment must be available and be vehicle-based so extra units can be placed rapidly into service. Remember the need for ALS equipment and portable radios.

- Have “high-rise” logistics kits available for remote treatment areas.

- Logistical support units (mobile medical caches) arc essential. LSIJs stock rapidly consumable medical hardware items such as backboards and oxygen, as well as software. Four of NYC*EMS LSIJs were constructed from retired/modified ambulances, reducing costs significantly.

- Well-intentioned media personnel may transmit improper instructions, such as to break high-rise windows. At the WTC incident, a public information officer (PIO) at EMS headquarters conducted a campaign to decrease the routine call load on the EMS system, reducing the call volume during the disaster and making it possible to render efficient service to the rest of the city.

- Crews must be monitored for

- their use of safety equipment (helmets, coats, etc.).

- Mobile safety officers are an asset and would have been beneficial in each division.

- All issues cannot be addressed on site during a disaster. An emergency operations center (EOC), especially if it is well-coordinated with the command post, can address many matters, including unit redeployment and personnel and staffing requirements for the disaster, as well as for routine community 91 1 service, and a host of administrative and operational needs as they arise.

- Consider the possibility of terrorist-related hazards, including the presence of “kill bombs” designed to draw crowds and rescuers and then to “take them out.” Keep in mind that terrorism is not just an urban problem — terrorists can strike anywhere.

- Rest and rehabilitation at the WTC disaster included CISI) and rotation of crews. They were essential to preserve the health and well-being of responders —especially since the crews were physically exerted by climbing to the upper reaches of the towers.

- When planning for rest and rehabilitation, do not forget officers Remember to meet their needs, as well.