Emergency Response To Questions on AIDS

FEATURES

HEALTH AND SAFETY

A train-the-trainer approach in California creates a network that gives emergency workers up-to-date information on infectious diseases.

After an ambulance crew transports a woman who’s ill, it’s learned from her relatives that the patient has AIDS.

That news travels swiftly through the station, causing questions and long-held fears to emerge. Soon, AIDS hysteria reaches its peak, and the only crew member who touched the patient is barred by other station personnel from cooking, cleaning, or using the bathroom facilities.

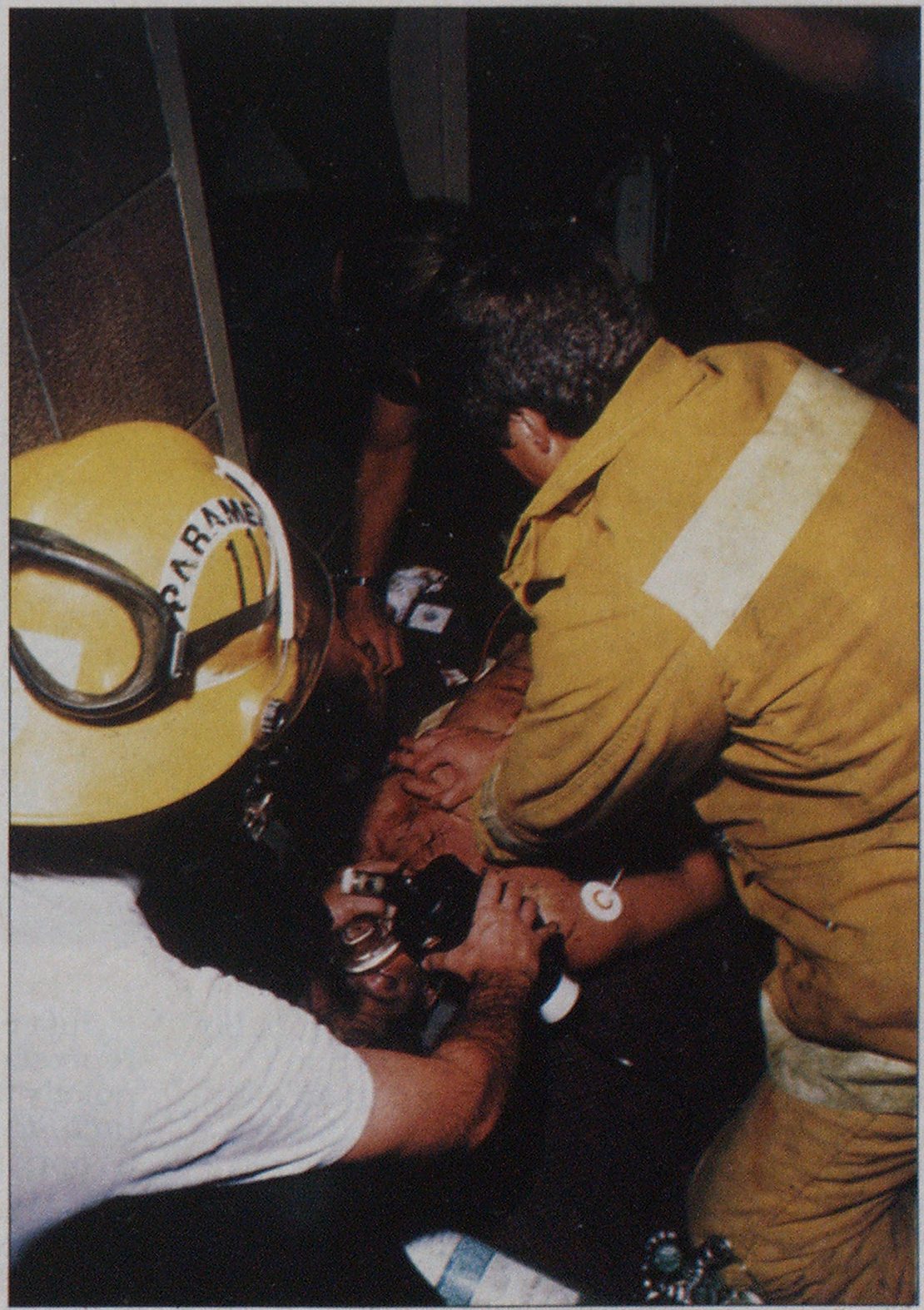

Photo by Keith Cullom

As extreme as that scenario may seem, it’s happened, and unless emergency response personnel learn the facts about acquired immune deficiency syndrome, it will happen again. In California, a statewide program designed specifically to educate emergency responders about the disease has flourished.

AIDS Education for Emergency Workers was started three years ago by the Sacramento area chapter of the American Red Cross, and is funded by the California Department of Health Services. The program trains certain emergency workers—those who have some experience in delivering information to others, interest in the subject, and the willingness to be used as an information resource—to teach line personnel about communicable diseases, including AIDS. This includes teaching what communicable diseases are, how to use safety apparel, and how to take proper precautions when handling blood and other body fluids. The program carries a minimal cost for materials, but other than that, it’s free to both departments that want to learn the course material and to individuals who want to present it.

Although there are many accurate articles on communicable diseases and emergency response, not all firefighters have access to them, or the information they contain ’might be outdated by the time they’re read. With this program, line personnel are taught from a standardized curriculum, and they’re more likely to feel comfortable asking questions of someone who understands the fire service.

But the most compelling reasons for the program are the questions raised, such as:

• I’ve been sent with the ambulance crew on emergency calls. What should I do if I accidentally get a needle stick from a dirty needle during one of these assists? Should 1 be tested for AIDS?

At the scene, you should clean off your wound; many firefighters carry disposable, disinfectant towelettes for this purpose. Once back at the station, you should report the incident on both the run sheet and the appropriate departmental form. Check you own immunization record for the date of your last tetanus and hepatitis B shots—there’s a much greater risk ^fcrfmtracting hepatitis B from a nwSle stick than there is of contracting the AIDS virus. Only if there’s reason to believe you’ve been put at risk for AIDS—such as actual blood-to-blood contact— should you consider having the test.

• I don’t care or believe what you say about AIDS being hard to get at work. I don’t want to work with or on a person who’s carrying the virus—period. What’s going to be done for me and my concerns?

Firefighting and other emergency work has always been risky; AIDS, in effect, is another risk. And when firefighters encounter a risk, the traditional response has been to develop a technique to handle it. In regard to AIDS, that means preventive measures: wearing rubber gloves, following proper cleanup and disposal procedures, and preventing exposure to body fluids. Also, learn the facts about AIDS—facts based on research on people with and without the virus-—before reaching any conclusions.

One fact that’s stressed in the California program is that no emergency worker has been infected with the AIDS virus as the result of his or her job, such as receiving a needle-stick injury or performing cardiopulmonary resuscitation.

Some questions about human immunodeficiency virus—the virus that causes AIDS—and safety precautions can be answered in general terms. But the training sessions also provide a forum for questions dealing with making or changing policy for an individual department.

Master trainers, the people who instruct departmental trainers, are taught by American Red Cross staff. Master trainers teach in pairs: One person is a health care professional—a nurse or a doctor, or someone from a local health department or community AIDS foundation; the other person is from one of the emergency services.

Master trainers establish a departmental training class by calling fire departments and ambulance companies to see if they’re interested in sending someone to be trained. In some cases, departments have called the program’s director or an AIDS foundation asking for a class in their area.

Departmental trainers attend two eight-hour training classes, during which they ask their own questions about AIDS and other communicable diseases, such as hepatitis. Their knowledge of communicable diseases is tested before and after the training. Master trainers then teach them the line personnel curriculum.

After the instruction, departmental trainers should be able to answer questions such as, ”What precautions should I take around blood and body fluids during an emergency response?”

The trainer would advise washing hands before and immediately after each exposure, even when wearing gloves; using disposable, disinfectant towelettes, if necessary; and wearing gloves whenever possible.

But departmental trainers aren’t expected to be experts on infectious disease; there may be questions that they don’t have the medical knowledge to answer. In these instances, they should know who or what agency in their community can answer the question, whether through a confidential hotline, a medical professional, or the local AIDS foundation. Gay and lesbian coalitions also make excellent information resources.

Prevention Guidelines for Emergency Response

If any good has come from the AIDS epidemic, it’s that emergency workers have been reawakened to the need for proper protection on the job. The International Association of Fire Fighters’ Department of Occupational Health and Safety publishes a booklet on the subject, based on its research and information from a variety of sources, including the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and manufacturers of protective clothing, equipment, and apparatus. The booklet, entitled “Guidelines to Prevent Transmission of Communicable Disease During Emergency Care for Fire Fighters, Paramedics, and Emergency Medical Technicians,” is excerpted here.

Because the infectious disease status of patients in the emergency care setting is usually unknown, all should be considered infectious. With that in mind, certain precautions should be followed in dealing with blood and bodily fluids:

- Sharp objects, such as needles, catheter stylets, and scalpels, should also be treated as if they’re potentially infectious, and handled with extraordinary care. Immediately after use, place them in puncture-resistant disposal containers; such containers should be in all transport vehicles, drug boxes, and intravenous-therapy kits.

- Structural firefighting

- gloves, such as those meeting federal Occupational Safety and Health Administration requirement 29 CFR 1910.156 or National Fire Protection Association Standard 1973, must be worn where sharp or rough surfaces are likely to be encountered. Victim extrication is an example.

- Disposable latex or vinyl gloves must be donned by all personnel before beginning any emergency patient care, specifically when blood or body fluid exposure is likely. Extra pairs must be carried on one’s person.

- Hands and other exposed skin surfaces must be washed vigorously and completely with a nonabrasive soap and running water after any direct patient contact, as soon as patient care allows. Hands must be washed immediately after gloves are removed.

- Pocket masks must be provided to all personnel who provide or potentially provide emergency medical treatment. Similarly, masks, goggles, gowns, and mechanical respiratory-assist devices—such as bag-valve masks and oxygendemand valve resuscitators— must be available on fire apparatus that respond or potentially respond to medical emergencies or victim rescues.

- Plastic goggles are the only acceptable form of eye protec-

- tion from blood or body fluid splashes. Structural firefighting helmet faceshields don’t protect the eyes, nose, and mouth from liquid splashes coming from below the face.

Cleaning and disinfection should be carried out as follows:

- Be aware of the flammability and reactivity of chemical disinfectants; use them where there’s adequate ventilation; and wear the appropriate protective clothing.

- Clothing grossly contaminated by large amounts of blood or body fluids must be placed and transported in bags that prevent leakage. Small stains from blood or body fluids may be “spot cleaned” and then disinfected. Contaminated clothing must not be laundered at home.

- Reusable medical equipment that routinely comes in contact with skin or mucous surfaces requires high-level disinfection or sterilization after each use and according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

The booklet, originally released last September, is already in its second printing. It provides detailed information on the points outlined here; copies are available from the IAFF.

Remember that the precautions listed above apply for any victim—even if it’s another firefighter.

Personnel should have a better understanding of AIDS and communicable diseases and emergency response after the course. For example, they should be able to define AIDS; identify two means of transmission; know ways to protect themselves from infection; and know the proper procedure for cleaning up spills of blood and body fluids.

The program is designed so that even after the training program is completed, line personnel can obtain accurate and up-to-date information about AIDS. There’s a network of resources available for all participants after the course has been completed. A newsletter providing the most current AIDS information is planned, and the project’s director, Monte Blair, is working on a 40-minute videotape for instructors.

AIDS Education for Emergency Workers in California has grown since its inception three years ago. Today, there are about 70 master trainers, 470 departmental trainers, and 8,000 line personnel from law enforcement, the fire service, and emergency medical services who’ve been taught. It will be presented as a model program at a major health education conference in August. There are many factors that contribute to its success, but the bottom line is this: Whether a department responds to 30 or 3,000 medical assist calls each month, information on AIDS and other communicable diseases should be presented in a way that’s understandable to the average firefighter.