fireEMS ❘ BY KATHERINE H. WEST AND JAMES R. CROSS

Every emergency response organization in the United States is required to have a designated infection control officer (DICO) who serves as a liaison between members/employees who have sustained exposures to communicable diseases and the medical facilities to which source patients involved in those exposures have been transported. Although not a new requirement, there is confusion in many departments regarding the role and responsibilities of the DICO. Fire and emergency medical services (EMS) departments have a legal responsibility to ensure exposed employees receive appropriate postexposure medical follow-up. The DICO’s job is to ensure that happens. This article will help chief officers and administrators to understand the responsibilities of the DICO, the importance of selecting an appropriate person to serve, and the need for the DICO to have full administrative support.

Webcast: What You Need to Know about COVID-19

Response Guideline to Respiratory Distress/Potential Coronavirus (COVID-19) Patients

The Designated Officer’s Role for Infection Control

Hands On Infection Control – The Flu

Book: Infection Control Policies for Community Paramedicine & MIH

History

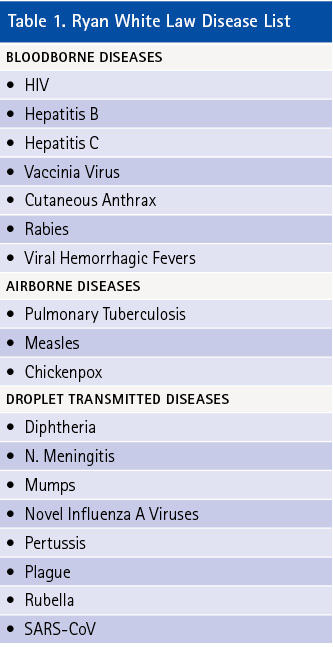

The Ryan White Care Act (1990) established a requirement for the DICO position. Although this act was primarily a funding bill for HIV programs, Subpart B specifically addressed fire/EMS personnel and exposures. The law also required medical facilities to cooperate with fire/EMS DICOs in providing patient disease information following exposure incidents. For bloodborne exposures, the medical facility must inform the DICO reporting the exposure whether the source patient was found to have a bloodborne disease. For airborne or droplet exposures, the medical facility must inform the DICO of the transporting fire/EMS department any time it is determined that a patient transported to that facility has or is suspected of having an airborne or droplet-transmitted disease. In the 2009 update to the Ryan White Law, the fire/EMS section was retitled Part G and included an expanded list of covered diseases. This new list of diseases was published in the Federal Register on November 2, 2011 (Table 1).

DICO Selection

One of the most important components of an effective infection control program is selection of the person who will serve as the DICO. Many departments simply select someone and do nothing more, which can be a disservice to the department and its members.

It is critical that the person selected has an interest in the DICO position and is committed to fulfilling its 24/7 responsibilities. The member should be eager to receive the necessary training; be self-motivated to stay current on applicable medical information and laws; have the trust of the department’s membership; be able to evaluate the exposure incidents reported by employees; have good organizational and interpersonal skills; set up an effective communication system and postexposure follow-up process; have the ability to develop a budget for vaccines/immunizations and postexposure evaluation costs not covered by workers’ compensation; and be committed to protecting confidentiality for exposed employees and source patients.

A key provision addressing the selection of the DICO in the Ryan White Law, Section 2695E (b), requires that the DICO be “trained in the provision of healthcare or in the control of infectious diseases.” Clearly, this is not a role for human resources or risk management personnel. The appropriate DICO will be a health care professional with training in making medical decisions regarding exposures.

Without appointing an appropriate DICO, departments face the likelihood that employees will not receive proper exposure evaluation and follow-up and risk noncompliance with legal requirements. Selecting the appropriate person requires care and should be based on established criteria.

Job Description/Statement of Authority

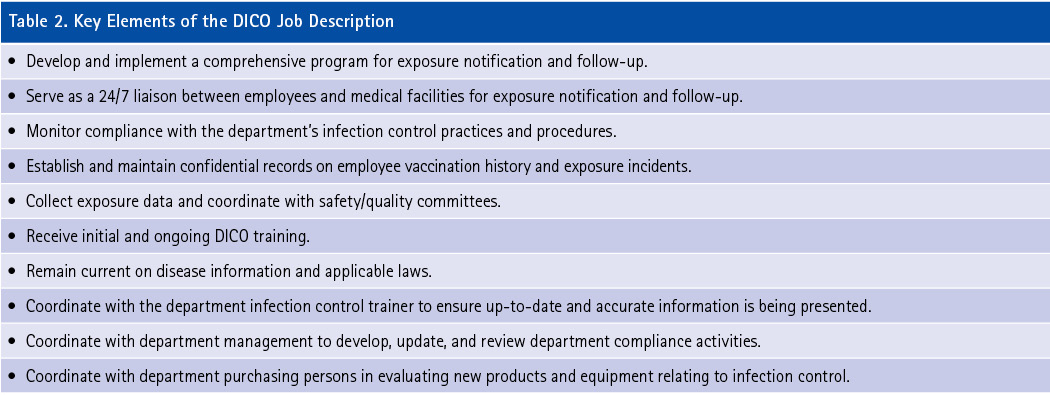

A job description containing a clear list of DICO responsibilities is an essential component of a successful program. It will enable department administration and members to have a full understanding of these responsibilities. Additionally, the job description offers legal protection for the DICO and the department under the department’s errors and omissions insurance policy. Key elements to be included in the DICO job description are listed in Table 2.

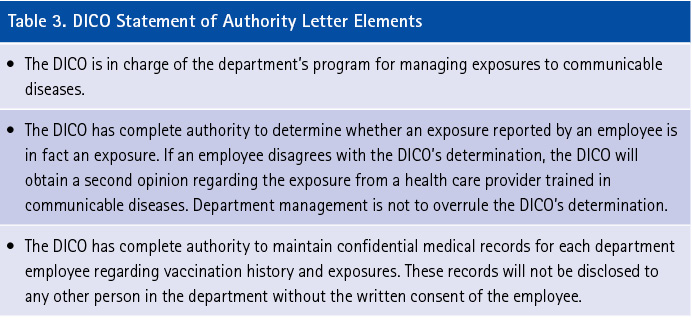

The DICO position bucks the historic chain of command in emergency services because the DICO manages exposure notification and follow-up, not the supervisor of the exposed member/employee. As a result, the DICO must have administrative support to ensure department management and that members understand the DICO’s responsibilities and line of authority. The chief can effect this by sending all personnel a notice containing the DICO’s job description and statement of authority. Table 3 includes key items to include in a Statement of Authority letter demonstrating administrative support for the DICO.

Postexposure medical follow-up processes can be jeopardized without documentation of administrative support for the DICO. For example, there are situations in which the DICO determines that an event was not an exposure, but the employee disagrees and asks his supervisor or the chief to overrule the DICO. It must be clear in the DICO’s statement of authority that this decision making is within the DICO’s authority. In circumstances where there is disagreement, a second opinion should come from a knowledgeable health care provider. Working outside of such a paradigm can significantly undermine the credibility of the DICO.

To avoid conflicts, the DICO should work with the infection control trainers to ensure appropriate training on what constitutes an exposure and what body fluids do and do not pose a risk to members. Department-based education and training must meet the requirements of the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) Bloodborne Pathogens Standard. This entails putting risk in a proper perspective by considering how exposure to bloodborne and airborne/droplet diseases is defined and keeping up to date on the latest information about diseases and testing.

Administrative support may also be needed in dealing with medical facilities. At times, facilities improperly require that an exposed fire/EMS member/employee register as a patient and have baseline testing performed. Fire/EMS personnel are not medical facility employees and, therefore, are not subject to the facility policies that might apply to their own employees. Any postexposure testing of an exposed employee is the responsibility of the fire or EMS department. The DICO must understand that he or she, on behalf of the department, is in control of postexposure follow-up and should not allow medical facilities to interfere with that authority. Department management should know that situations like this arise regularly and the DICO will need appropriate administrative support.

Testing the Source Patient

The proper focus of medical facility testing following notification of a responder exposure is testing the source patient, not the emergency responder. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) guidelines recommend that all testing begin with the source patient. This is the responsibility of the medical facility and that is where all follow-up begins. The DICO needs to work with medical facilities to ensure that rapid testing for HIV, hepatitis C, and syphilis is performed on the source patient. Currently, there is not a rapid test for hepatitis B, so those results will be available the next day; this rarely poses an issue because most responders have been vaccinated for hepatitis B and are protected.

Medical Records

The DICO also needs administrative support relative to medical records. A DICO requires 24/7 access to vaccination and childhood disease information on each member/employee, according to CDC guidelines. This is important for verifying employee status and jump-starting postexposure medical follow-up if needed. For example, if an employee is exposed to chickenpox—and that employee has documentation as either having had the disease or having been vaccinated—then no medical follow-up is needed or recommended.

In addition, it is important that the DICO be aware of proper postexposure medical follow-up for each potential disease exposure. Changes in postexposure medical follow-up recommendations occur often, and the DICO needs to be up-to-date. DICOs should also understand that not every health care provider is thoroughly knowledgeable about postexposure follow-up, so they should not assume that what they are told is always correct. The DICO is acting to protect not only the exposed employee but the entire department from less than optimal care and follow-up as well as the resulting potential legal liability. Physicians conducting postexposure care and counseling are acting as “agents” on behalf of the department. The department holds the legal liability!

References

Ryan White Care Act, 2009, Notification of Possible Exposure to Infectious Diseases, Part G, Section 2695.

West K and Cross J. “The Designated Officer’s Role for Infection Control.” Fire Engineering, January 1, 2012.

Federal Register. Volume 76, Number 212 (Wednesday, November 2, 2011), 67736-67743.

29 CFR 1910.1020, Medical Records Standard, Occupational Safety and Health Administration.

CPL 02-02.069, Enforcement Procedures for the Occupational Exposures to Bloodborne Pathogens, November 2001.

Prevention of Hepatitis B Virus Infection in the United States: Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. MMWR. January 2018.

Update Post Exposure Follow Up HIV. CDC, January, 2019.

Tuberculosis Screening, Testing, and Treatment of U.S. Health Care Personnel: Recommendations from the National Tuberculosis Controllers Association and CDC, 2019. MMWR, May 17, 2019.

KATHERINE H. WEST, BSN, MSEd, lectures nationally and internationally on infection control and publishes books, training materials, and articles on related issues. She has been a consultant to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health and an education specialist for the National Institutes of Health. West wrote the Infectious Disease Handbook for Emergency Care Personnel, third edition. She is a consultant to the U.S. Public Health Service, Federal Occupational Health.

JAMES R. CROSS, JD, practices in discrimination and employment law, serves as a legal analyst for infection control/emerging concepts, and has been involved in infection control issues since 1990. He taught a course on the emergency medical services and the law at George Washington University, Washington, DC. Cross has published several articles concerning infection control and EMS.