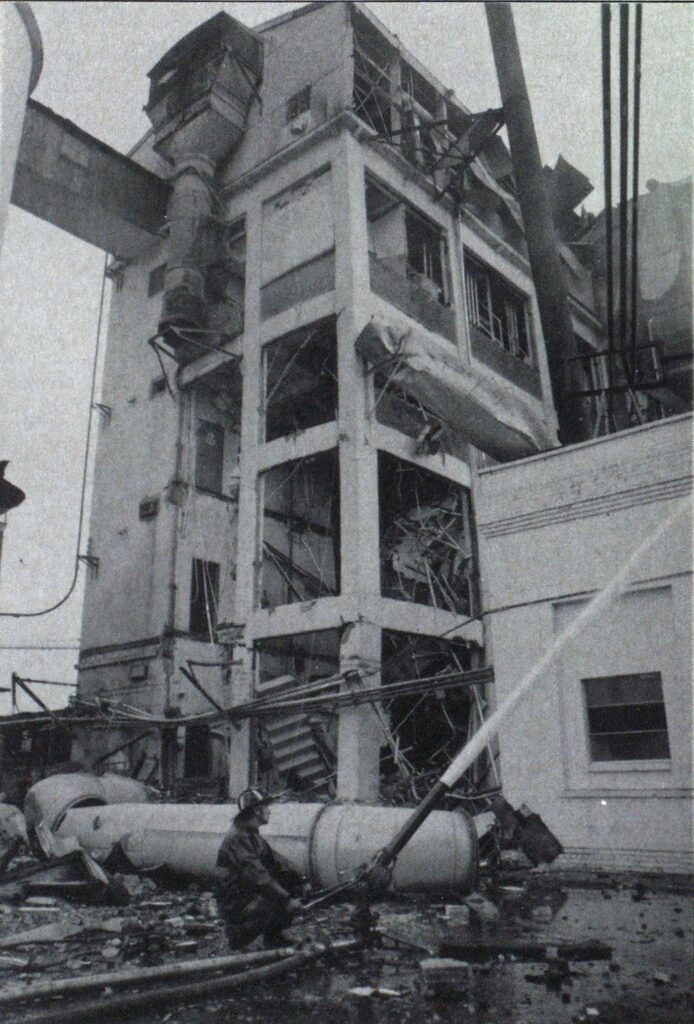

Dust Explosion Destroys New Jersey Flour Mill

SPECIAL RISK FIRES

The first known incident of a dust explosion occurred in 1785 in a Turin, Italy, flour mill. Today, according to a report in DUST EXPLOSIONS by Peter Field (Elsevier Scientific Publishing Company, Amsterdam-Oxford-New York), there are an average of 40 dust explosions and one resulting fatality each year.

When compared to other combustible dusts, wheat flour explosions are considered strong, capable of attaining a maximum overpressure of 97 psig. The maximum rate of pressure rise is about 2,800 psi per second.

On November 18, 1984, an early morning dust explosion at the Bay State Milling Company’s flour mill in Clifton, NJ, claimed the life of one employee and seriously injured three others. It took more than 40 firefighters to bring the incident under control.

Flour had been produced at this milling site since World War I. Over the years, the mill had experienced some minor fires and explosions, but none as serious and devastating as this incident.

Several buildings comprised the entire Bay State complex. The main five-story grain elevator and mill operations building where the raw grain was processed into flour was centrally located. It was here that the dust explosion was initiated. The structure had steel reinforced concrete walls and floors, concrete pilasters, structural steel members, and lightweight corrugated steel panels on some exterior portions of the building.

Photo by Bill Clare

Attached directly to the east and west sides of the main elevator/mill building were two storage warehouses. Measuring 50 X 100 feet each, the warehouses were onestory high and of ordinary brick and joist construction. The east warehouse stored bags of flour awaiting shipment; the west warehouse contained various materials used throughout the plant.

About 30 feet away from the mill to the east was a packaging plant for the complex. This two-story structure (50 X 75 feet) was constructed of steel with lightweight corrugated steel panels on the exterior.

Adjoining the mill’s north side was a set of railroad tracks where hopper cars containing raw grain would unload into the mill. Down a sloping embankment beyond the railroad tracks is Clifton’s Department of Public Works garage. This one-story block building was approximately 75 feet from the mill.

About 12 large raw grain storage silos were located along the mill’s south side, about 25 feet from the mill building. A small bridge conveyor between the silos and the mill carried the grain to the mill for processing.

At approximately 1:16 A M., a violent dust explosion rocked the Bay State complex. A flood of phone calls were received by the Clifton Fire Department communications center, reporting an explosion and fire at the flour mill.

At 1:17 A.M., the first-alarm assignment was dispatched, bringing two engine companies, a combination engine with a 75-foot rear mount aerial ladder and a deputy chief.

On arrival, the units found the main mill building severely damaged by the explosion. Large sections of the eight-inch thick reinforced concrete walls were blown loose and some portions were hanging precariously by their steel reinforcing rods. Some of the corrugated panels on the exterior of the mill had been blown as far as 300 feet away, while others had simply been peeled down like a banana. Fires were burning in many portions of the mill and large amounts of debris were falling, making the structural integrity of the building highly suspect.

Larger fires were burning in the attached storage warehouses, and fires had also been started in a few of the railroad hopper cars adjacent to the mill.

The explosion had ripped portions of the corrugated steel from the packaging plant and had blown down a 125-foot portion of the public works garage.

Firefighters were informed by plant managers that some plant employees were trapped in the wreckage.

The incident went to a second alarm at 1:23 A.M., bringing another engine and a truck company. Chief of Department Joseph Colca arrived with the secondalarm assignment. He ordered a general alarm at 1:39 A.M., bringing two more engines to the scene. Requests for mutual aid assistance brought three engines from Paterson at 1:45 A.M., and one aerial ladder from Passaic at 1:49 A.M. Two ambulances also responded to the scene.

As Engine 3, the combination engine/aerial unit, arrived on the scene, it was evident that it should make use of its ladder pipe capabilities.

Lieutenant James Lyons ordered his company to operate a water tower on the mill’s west side warehouse.

As his company was setting up, Lyons began to search for any possible survivors of the explosion. Nearing the large mill building, he heard the cries of a person apparently trapped inside. He entered through a large hole in the side wall of the structure and followed the direction of the moans. The cries were coming from the basement area.

Continuing to grope in the direction of the cries, Lyons found James Smith prone and suffering from a broken leg and burns. The unsafe condition of the structure forced Lyons to try to remove Smith immediately. While dragging his charge to safety, Lyons heard an additional cry. Another person was trapped in the structure.

With Smith removed to the outside, Lyons returned to the basement with his company. They began another search to locate the second victim. The cries were no longer heard. They were unable to locate the unknown victim.

Additional debris began to rain down everywhere within the structure. Chief Colca made the difficult decision to call off the interior search operation, as it was then too dangerous for the firefighters to continue interior operations.

Photo by Glenn P. Corbett

Photo by Bill clare

Companies operated large caliber streams on the main bodies of fire in the two warehouses and in the mill, and knocked down the fires in the railroad cars. The warehouse fires were quite deep-seated and continued to burn for several hours. Streams were also placed on the conveyor bridge to prevent any extension of fire from the mill into the silos that were undamaged by the explosion.

At about 3 A M., spectators noticed another plant employee, James Holsman, as he crawled from the basement of the mill near the railroad siding. Holsman, who suffered burns over 80% of his body, was taken to a hospital burn unit where he died several days later.

At 8 A M., five hours later, as the fire was being declared under control, the third victim was spotted crawling out onto the fourth floor fire escape balcony. This fire escape structure was avoided by fire forces because the explosion had severely damaged its supports.

The balconies at some levels had come away from the building and were hanging precariously from the building’s siding. Access to the victim’s location was impossible by aerial or portable ladder operations because of the siding tracks below and the grain hopper cars located thereon.

Extraordinary courage of the firefighters was evident as two members were assigned to ascend the unsafe hanging fire escape to attempt to remove the severely burned victim.

Fires continued to smolder in different areas of the mill for a few weeks. Clifton fire units were forced to maintain a watch line and units returned to the scene several times to extinguish continually erupting hot spots. It was not until demolition operations were begun within the compound that access to the seat of most of the fires was finally provided and final extinguishment accomplished.

Critique gives its lessons

As should be the case with all fire and emergency operational responses, a critique was held as soon as possible in order to gather lessons that would help with future fireground strategies and tactics. There appeared to be several that were unique at this particular response:

- The value of separation of buildings by distance and/or construction within commercial occupancies, especially if of a hazardous nature.

- Fire departments should preplan for the possibility of dust explosions at commercial occupancies within their district no matter how small the operation.

- Our pre-plan activities were of inestimable value. We knew layout, life hazard, occupancy, hazardous area, fire protection installations available, etc. Our liaison person in charge was able to inform us immediately of the location of the explosion and fire and also of the number and probable location of unaccounted for civilians.

- At explosion incidents, the integrity of the structure is a major problem. If the building is not collapsed on arrival of the firefighting units, its extreme weakness presents a more serious problem.

- Once visible life is accounted for, the firefighters’ safety is of paramount importance. Re-establishing stability of the search/collapse scene must have priority.

- In keeping with the foregoing, discipline at the scene is a problem that must be planned for. Civilians must be controlled. Anxious firefighters become a safety problem after the fire is under control. Operations within the collapse zone must be done with a minimum amount of personnel involvement. Additional firefighters must be given other tasks or released from the scene for their own safety.

- Communications were a problem that will be solved in the near future. Units responding as mutual aid were equipped with different frequencies, making early coordination near impossible. The dispatch center was overburdened with the heavy informational traffic that can be expected at large-scale incidents of this nature. Staffing (recall) measures should be established to account for this possibility, especially in more urban areas.

- Lack of coordinated cooperation between responding municipal departments was a problem. This was determined to be based on poor interagency communication and education and the guidelines for large-scale emergencies.

Continued on page 26

Continued from page 24