By CONNIE PIGNATARO

In the world of emergency medical services (EMS), avoiding complacency can often be challenging. Take, for example, the lonely, elderly lady who calls every other day for abdominal pain or the homeless, inebriated man who frequently calls for chest pain, only to admit later that he just wanted some food and a warm bed in which to sleep. The 20th time we respond to the elderly lady for abdominal pain at 0300 hours, we put her in the rescue and take her to the hospital without any treatment. We tell ourselves she is just lonely and needs attention; the same goes for the homeless man. But this time, one or both is suffering from a cardiac event that was missed because of complacency. Complacency can also come into play in a lesser known yet deadly disease called Brugada Syndrome.

Brugada Syndrome is a genetic disorder that can lead to sudden cardiac arrest in an otherwise healthy person. It is also known as Sudden Unexpected Nocturnal Death Syndrome.1 The most common symptom is syncope, which may or may not include nightmares or thrashing at night. Fever and cocaine use can trigger or exacerbate the clinical manifestation as well as hyperkalemia, hypokalemia, hypercalcemia, or alcohol intoxication. A family history of sudden cardiac death may also be common. The typical patient is a young male (30 to 50 years old) who is otherwise healthy with normal general physical and cardiovascular exams.2

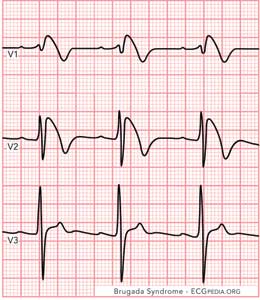

The only way to diagnose Brugada Syndrome is through an electrocardiogram (ECG) with two distinct patterns or types of ST elevation. Although three patterns of ST elevation were used in the past to diagnose Brugada Syndrome, recent consensus describes only two, with type 2 combining what used to be type 2 and type 3. (1)

In type 1, the elevated, coved-type ST segment (> 2 mm) gradually descends to an inverted T-wave in more than one right precordial lead (V1-V3) (Figure 1). This finding, along with a history of documented ventricular fibrillation (v-fib) and self-terminating polymorphic ventricular tachycardia (v-tach), a family history of sudden cardiac death, family members with coved-type ST elevation, the ability to induce the ST elevation with medication, and syncope and/or agonal nocturnal respirations, confirms the diagnosis of Brugada Syndrome. Also, several genetic mutations can lead to a diagnosis of Brugada Syndrome, which requires genetic testing.3

| Figure 1. Type 1 Brugada Syndrome |

|

| Figure 1 courtesy of ECGpedia.org. |

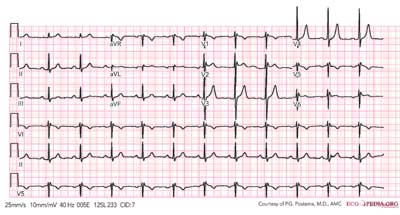

The type 2 ECG will be identified by a saddle-back ST segment elevated to one mm or greater in more than one right precordial lead. The ST segment descends toward the baseline, then rises again to an upright T-wave (Figure 2). (1) Although a type 2 ECG is not a positive diagnosis of Brugada Syndrome, it should be strongly considered and tested further. Testing consists of administration of a sodium channel blocker such as procainamide, flecainide, pilsicainide, or ajmaline followed by an ECG to see if the type 2 is induced into a type 1. (3)

| Figure 2. Type 2 Brugada Syndrome |

|

| Figure 2 courtesy of PG Postema, MA, and ECGpedia.org. |

Once Brugada Syndrome is diagnosed, the only therapy currently known to manage it is an implanted cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD). For those who are asymptomatic, controversy exits regarding treatment. One option is to take a “wait and see” approach; however, the first symptom may be sudden cardiac death. Others may choose to have the defibrillator implanted, especially when there is a family history of sudden cardiac death. (3)

So, how does complacency come into play with Brugada Syndrome at the EMS level? Imagine again you are dispatched to a call of a male who experienced a syncopal episode when he got up to go to the bathroom in the middle of the night. Your patient is 45 years old, has no medical history, and takes no medications. He has not been feeling well all week and has a fever. He also tells you he has been putting in a lot of hours at work recently. Most protocols dictate that we perform a 12-lead ECG on someone who experiences weakness or syncope. The medics on scene may think the patient has the flu or is just tired, but they do an ECG anyway and find type 1 Brugada Syndrome. Because they are familiar with Brugada Syndrome, the medics immediately apply fast patches and monitor the patient’s rhythm closely. The patient suddenly goes into a pulseless ventricular tachyarrhythmia, like v-fib or v-tach, but the crew is prepared and immediately defibrillates the patient, saving his life.

Now, imagine the complacent scenario where the medics simple transport the patient without any ECG monitoring. While en route with one person in the back, the patient goes into cardiac arrest. Without immediate defibrillation, the patient will most likely die. Because of complacency, this crew is “behind the eight ball,” and the lives of the family of this patient will be forever changed.

We may not even get the opportunity to discover Brugada Syndrome in a patient. Sudden cardiac arrest is the initial presentation of this disease in one-third of patients. (1) Of all patients without significant medical history who experience sudden cardiac arrest, five percent of them survive and show no cardiac abnormality. Fifty percent of these survivors are thought to have Brugada Syndrome. (2)

Brugada Syndrome was first described in 1992 by Pedro and Josep Brugada.4 It is primarily diagnosed in adulthood, with the mean age of sudden death from the syndrome being 40 years old. The youngest to be diagnosed with the syndrome was a two-day-old newborn, and the oldest was 85 years old. (3) Although females have been diagnosed with Brugada Syndrome, it is nine times more likely in males, who also have higher incidences of associated syncope and death. (1) A child of a parent with Brugada Syndrome has a 50 percent chance of inheriting it. (3)

Studies are finding that the majority of those affected by Brugada Syndrome are of Asian descent. (1) In Southeast Asia, it is considered to be a major cause of sudden cardiac death in younger adults, especially in Thailand and the Philippines, where the prevalence of Brugada Syndrome is estimated to be five per 10,000 people. (4) This endemic disease is a leading cause of death in men under the age of 40, second only to automobile accidents. (3) In Japan, 0.12 to 0.16 percent of the population have type 1 Brugada Syndrome. (1)

Although eight different genetic mutations are responsible for Brugada Syndrome, a mutation in the SCN5A gene is the most common cause of the disease. (1) More than 100 mutations of this gene have been linked to this syndrome. (4) SCN5A encodes the alpha subunit (a single protein molecule) of the cardiac sodium channel gene. Because of this mutation, normal sodium channel activity fails, causing alterations in voltage and accelerated or prolonged recovery from inactivation. This mutation has been found in 18 to 30 percent of families that have Brugada Syndrome, which may explain why the administration of sodium channel blockers exposes the syndrome. (1)

Those with the poorest prognosis are males with spontaneously abnormal ECGs and easily inducible sustained ventricular arrhythmias. They have a 45 percent lifetime likelihood of having an arrhythmic event. (3)

It is not unusual to find other overlapping diseases with Brugada Syndrome such as first-degree AV block, intraventricular conduction delay, right bundle branch block, and sick sinus syndrome. (3) Those with the syndrome also have an increased risk of atrial fibrillation (a-fib) with an incidence of 10 to 20 percent. With the presence of a-fib, there is a higher risk of the patient developing v-fib. The most common type of v-fib observed is polymorphic, resembling a rapid Torsade de Pointes. (4) In a study of 611 patients with Brugada Syndrome, the diagnosis of a-fib preceded the diagnosis of Brugada Syndrome in nearly six percent of the patients. (1)

Initially, those diagnosed with Brugada Syndrome were thought to have structurally normal hearts. After further study, subtle structural or microscopic abnormalities were discovered such as dilation of the right ventricular outflow tract, localized inflammation, and fibrosis. (1) In another study of 18 patients with Brugada Syndrome, most were found to have inflammation of the myocardium (myocarditis), and all had abnormal biopsy results of the right ventricle. (4)

As previously noted, the only effective treatment for Brugada Syndrome is an ICD. In an early study of 63 patients, 35 patients received an ICD, 15 patients received pharmacological therapy, and 13 patients received no therapy. The patients were followed for three years; 32 percent developed ventricular arrhythmias. None in the ICD group died, but deaths occurred in the pharmacological group (26 percent) and in the untreated group (31 percent). (1)

For Jack Emperor, the ICD was a lifesaver. Back in 1974, his 48-year-old father died in his sleep, leaving behind a wife and seven children. He exhibited no signs or symptoms of any health conditions, and the coroner stated his structurally healthy heart “just stopped.” In 2002, one of Emperor’s siblings went to a specialist with symptoms that pointed toward Brugada Syndrome.5 The specialist strongly recommended that the entire family have ECG testing. Emperor then faxed his ECG and medical records to Dr. Ramon Brugada, Brugada Syndrome expert and brother of Pedro and Josep, who initially introduced the disease. Ten minutes later, Emperor received a call from Dr. Brugada, diagnosing him with Brugada Syndrome. With Dr. Brugada’s help, Emperor found a specialist and received an ICD. He also had the stark realization that if the medical profession knew about Brugada Syndrome back in the ’70s, his father might be alive today. (5)

As fire EMS providers, we can make a difference every day. With knowledge of Brugada Syndrome and a proactive approach of performing an immediate ECG on a person exhibiting signs and/or symptoms of the disease, we offer patients with this disease a much better chance for survival.

ENDNOTES

1. Wylie, JV and Garlitski, AC. Brugada Syndrome. In: UpToDate, Manaker, S (ED) and Asirvatham, S (ED), UpToDate, Waltham, MA, 2013.

2. Dizon, JM and Nazif, TM. Brugada Syndrome. Medscape. http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/163751-overview. February 15, 2013.

3. Brugada R, Campuzano O, Brugada P, et al. Brugada Syndrome. GeneReview™. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK1517. August 16, 2012.

4. Antzelevitch, C. Brugada Syndrome. National Institute of Health. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1978482. October 29, 2006.

5. Emperor, J. The Story of My Father, Jack Emperor. Brugada Syndrome. http://www.brugada.org/lifestories/emperor.htm. March 2004.

CONNIE PIGNATARO is a lieutenant for Oakland Park (FL) Fire Rescue (OPFR), where she has been a member since 2002. In 2011, she was the first female to be promoted as an officer for OPFR. Pignataro has a bachelor of applied science degree in public safety administration. She was introduced to the field of fire rescue as a volunteer for her local community emergency response team in 1998.

Fire Engineering Archives