By JEFF SIMPSON

Current global news events have reinforced the idea that we need more than ever to expect the unexpected. Planning and preparation in the emergency services arena are critical; we continue to handle thousands of “routine” things that we do and continue to face more complex challenges.

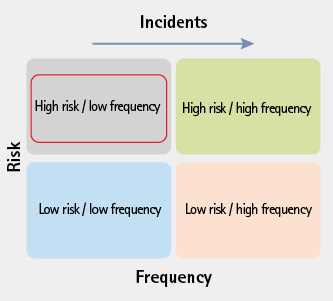

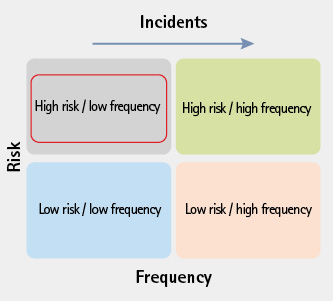

Recently, I presented Gordon Graham’s online video “High-Risk/Low-Frequency Events in the Fire Service” to the U.S. Fire Administration. I have seen it many times and use it to refocus my understanding on leadership and how the highest consequences occur during low-probability events—where most of the mistakes happen. These errors typically lead to issues in civil court and involve personal injury, organizational embarrassment, or both (Figure 1). Inherently, our service’s “DNA wiring” is based on the critical aspects of time with the goal of completing complex tasks more quickly and correctly and with our best efforts done safely. We then add in some functional common sense, dignity, respect, and incident documentation to affect the limitation of liability, raise our levels of customer service, and strengthen personnel welfare.

Developing Knowledge, Skills, and Abilities

The many common routine events we deal with establish an experience level filled with lessons learned and best practices that we then apply to do those things effectively and safely. The approach we use to address those rare, risky events with a high level of consequence has not been forged through years developing our knowledge, skills, and abilities (KSAs). These significant incidents typically occur when there is little to no time available to develop strategies and tactics to successfully influence the outcome. Reactionary decisions are often implemented when we are faced with unknown, untested events.

The talent to make thorough, timely decisions during an emergency event is crucial. Good problem solving and decision making can avert catastrophe and help the community you serve recover from the event more quickly. Equally, poor decision making—or the failure to make decisions—can result in injury or death to victims and public safety personnel. In addition to creating a disastrous end result, poor decisions made in the primary stages of an incident may have surging effects over time and can make the job of public safety responders more difficult and dangerous. Poor decisions can also cascade into much more critical or complex problems later on that may affect the population’s ability to recover from the incident. Are you or someone in the organization reviewing the after-action reports from recent global events that fit into the “no-time-to think-it-through” events? What lessons are you taking away from them?

Figure 1. Organizational Chart for Fire Department High-Risk Event Response

Since our experience database is not populated with vast amounts of KSAs that involve prime decision making for high-risk events, Graham correctly points out that we must slow down (yes—slow down) with the goal of getting the job done right; reducing errors; and, with our best efforts, doing so without harm. He contends that by using the method of studying consequences, you can identify those high-risk, low-frequency, no-time-to-think-it-through events that could occur in your community. By starting with the overarching question, “What will we do if this happens?” you can plan for most unexpected events and develop and exercise a system for robustness through effective training when you are afforded that all important time to “think it through.” Emergency response professionals can develop the ability to identify potential and follow-up problems that they can address with timely and sound decisions before and during an emergency. Those decisions not only affect those initial response resources but also impact the ability of other mobilized agencies that can make the critical difference in how quickly the constituents can recover from an event, whether it is a man-made or natural disaster.

Graham reinforced this point when I was fortunate enough to sit next to him on a flight to Atlanta. He had just finished addressing a convention of the state’s police chiefs when he asked the question of how many of the more than 100 police chiefs had reviewed the after-action report from the Ferguson, Missouri, riots in 2014. Less than 10 percent of the audience acknowledged taking the opportunity to learn from and develop their “What if that happens in my jurisdiction?” high-risk plan. Feedback, on average, would suggest that jurisdictions operate from two vantage points regarding strategic planning for emergency operations. Either they have a complex, mostly outdated, unexercised plan that fills the volume of a large three-ring binder, or they operate without any guideline plan for managing complex incidents.

A Framework for Managing High-Risk Events

The challenges known and unknown are dynamic as well as perplexing in nature. Our strength is driven from our ability to be flexible, adaptive, and solution based, so creating a similar framework approach to managing extremely difficult and hazardous challenges should be the goal. Leaders in public safety response organizations must make a complete and honest assessment of just how well their administration is prepared to respond to a complex incident and then take the necessary steps to remedy any deficiencies.

Using this framework to create a simple, effective, and exercisable method to managing varying high-consequence events begins with a stepped process approach. Some suggestions include the following:

- Identify high-risk, low-frequency priority events most likely to occur in your community. Conduct a target hazard assessment that could be impacted by man-made and natural disasters with a focus on the assembly of large numbers of people. This could include modes of transportation, schools, hospitals, churches, convention centers, neighborhoods, shopping malls, and so on.

-

Based on those events, determine the capabilities, barriers, and challenges to your organization. What are the strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats that you perceive? Conduct a needs and gap analysis for areas involving evacuation needs.

- Human resources. What public safety personnel are available now, how do you mobilize additional help, and is there a consistent number of response personnel available for your preidentified sources? Do you have a process for calling back off-shift personnel? Who covers your current call volume for service outside your major incident? How long will it take them to get to the location?

- Physical assets. What equipment and logistics support are available? How do you mobilize more assets? Are purchasing contracts in place to secure specialized equipment and sustaining items? Are your needs specific to time of day and time of year? Do you use the National Incident Management System (NIMS) typing standard to identify resources, and do you have a method to catalog and track those assets that don’t fit into the standard?

- Mutual aid. Are agreements already developed for the response of human and capital assets from local, state, and federal jurisdictions? Do your local community leaders need to enact a declaration of emergency to clear the path for outside agency support? How do you notify and engage specialized teams from the various public safety agencies? What are the additional beneficial resources from the community including those from faith-based organizations, civic-minded councils, and the private and volunteer sectors? (These include home health care; animal control, welfare, and veterinary agencies; disability services; food pantries; shelters; and prescription medicine dispensaries.)

-

Develop flexible and realistic incident priorities based on conditions. Based on the event with which you are faced and your initial assessment of the limitations and capabilities, formulate an action plan that focuses on the first hour of operation. Follow this up with a compartmentalized block-of-time approach to make forward progress for the next hour or two (or four or 24). Note that your first-hour goal may be simply to accomplish one or more of the following:

- Size up the incident. Assess the incident’s current footprint and potential for incident expansion. Gather information on the event’s potential scope to include location, size, and human hazard and if exposures involve physical and environmentally sensitive conditions. Consider unique hazards such as bridges, tunnels, and terrain.

- Safety first! Approach the scene upwind, uphill, and upstream. Use personal protective equipment and self-contained breathing apparatus that match the hazard and air/water monitoring equipment readings.

- Secure the scene. Establish a security perimeter; control access; consider you may have an active crime scene; determine access routes; and establish an exclusion hot zone, contamination-reducing warm zone, support cold zone, and so on. Decide who or what can be on site and where. Allow key personnel immediate access (with proper ID credentials).

- Establish incident command. Select and communicate the initial location of the command post and consider alternatives if the incident expands. Prepare for an increasing command structure with established roles, responsibilities, and accountabilities.

- Provide notification. Mobilize additional resources and capital to support your operation using the NIMS organizational model to fill key roles in safety, public information, agency liaison, logistics, planning, operations, finance, and administration with government officials. If a unified command approach is required using key coordinating public or private agencies, priority activation is required.

- Evacuation. With life safety as an overarching goal, consider the need for triaging and moving victims; activate notification for shelter-in-place (reverse 911) or voluntary/mandatory evacuation orders; and enable plans for hospital escalation, evacuation, transportation, large shelter, and logistics support that includes medical supplies, pet and animal support, infant and senior care, and so on.

- Define which supportive and coordinating agencies must be involved and how to notify them. Based on your assessment of the capabilities, barriers, and challenges, formulate key “trigger points” or tiers for activating the additional staffing and physical assets needed to support your incident operation. Also, clearly define the mechanisms required to automatically provide this activation notification. Investigate what constitutional requirements exist to help or complicate your activation protocols. Does your municipal charter require a local emergency declaration to help assign regional, state, or federal assets? Do you have memorandums of understanding in place to allow for mutual-aid automatic assistance including funding agreements or reimbursements?

- Formulate your plan based on the information gathered. Common operating platforms exist for all complex high-risk/low-frequency events. Up-to-date and reoccurring situational status information will dictate adjustments to your operational stages, but your predefined framework will allow for faster execution when establishing your foundation approach. The statement, “What you do in the first five minutes will dictate what happens in the next five hours,” applies here.

Transitioning to the next block of incident management time may require filling key positions within the command and organizational structure. Be mindful of how, where, and when to assemble the host of mutual-aid and other public or private assets that will arrive at your incident. This includes agency representatives from every level of government; the news media; and public officials that have interest in the event’s scope, impact, and plans to alleviate any danger. You may also need to “ramp up” logistics support to maintain the variety of assets you engage or request for multiple operational periods, seasonal weather conditions, terrain, and time of day.

Because of the potential shortage of resources, it is essential to be proactive in securing additional assets as required. If you are not familiar with the NIMS resource typing system, it is helpful to use the acronym CSALTT:

- Capability. What is the resource’s indicated use, and what do you want to accomplish?

- Size. What is this resource’s specific parameters or required specifications?

- Amount. Identify quantity in detailed measurement.

- Location. Define the specific address or geography for resource reporting, delivery, pickup, deployment, and so on.

- Type. Similar to Capability, provide classification with a precise description of the resource.

- Time frame. When do you need the resource, and for how long?

In addition to establishing a unified command, develop current and future incident objectives. For instance, create canned single-page guidelines and fill them in with the critical elements for any incident situation; this will help provide a briefing to the news media to help update your agency administrator with the current status and the impact of ongoing plans of action.

As Graham wisely suggests, the development and—more importantly—the testing, training, and revision for strengthening your KSAs to address those high-risk, low-probability, high-consequence events must be done immediately and with all the seriousness for when such an event occurs in your jurisdiction.

References

JEFF SIMPSON is a 35-year fire and emergency medical services veteran and a former chief of the Salisbury (MD) Fire Department. He has progressive degrees in engineering, management, and public administration and is certified as a state fire instructor and Federal Emergency Management Agency-level safety, emergency management, and command officer and is the former training chairman of the Central Virginia Type 3 All Hazards Incident Management Team. He sits on the American Military University Industry Advisory Council and advises on its emergency management, fire service, and disaster preparedness curriculums. Simpson lectures nationally including for the International Association of Fire Chiefs on handling emergencies involving regional rail response, alternative energy, and firefighter safety and survival. He has written many articles for Fire Engineering and was a 2006 Governor’s Award Finalist for Excellence in the Virginia Fire Service.