DERAILMENT AT SEACLIFF

Photos courtesy of Ventura County Fire Department.

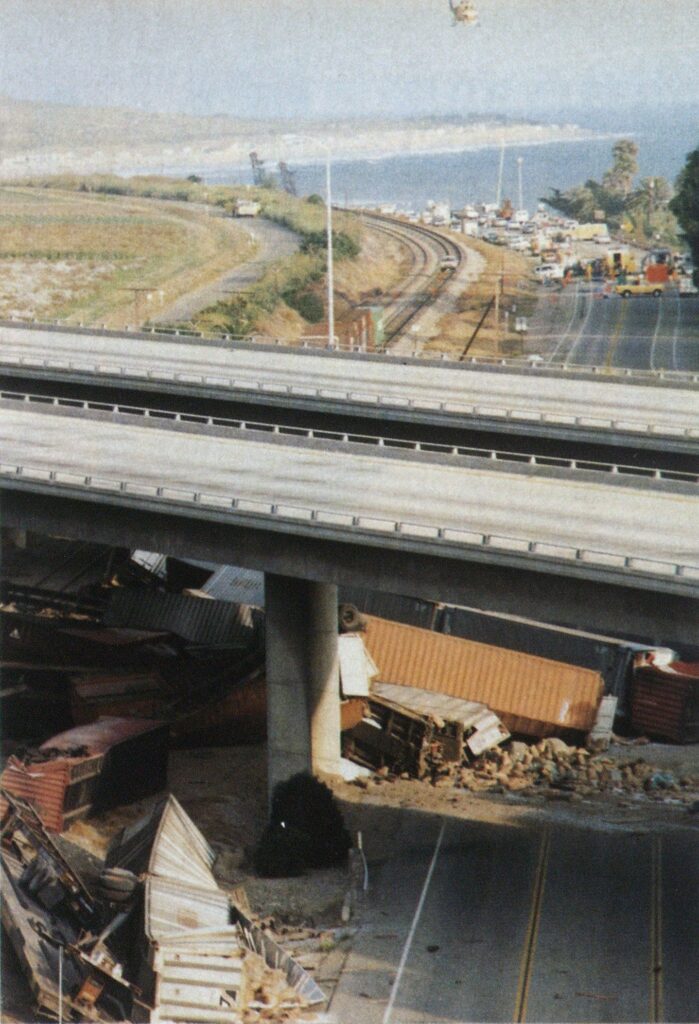

At 1205 hours on Sunday, July 28. 1991. Station 25 of the Ventura County (CA) Fire Protection District received an alarm for a railroad right-ofway fire adjacent to Pacific Coast Highway, two miles south of the station, just north of the quiet seacoast community of Scacliff. From the station, firefighters observed a derailed train just a few hundred yards south of tile station, with cars and cargo strewn beneath the 101 Freeway overpass. The train’s engine and several cars had continued on the track until coming to rest more than a mile beyond the wreckage.

While en route to the crash site, Captain Ken Bigger of Engine 25 requested an upgraded response, lie directed the apparatus to be positioned about 50 yards north of the site. From there, bigger observed a white cloud building in the wreckage but no fire, believing that they could be facing a potentially serious hazardous condition, his immediate strategic concerns became life safety, isolation, entry denial, notification, and identification of the involved material:

Bigger requested that traffic on the 101 Freeway and the Pacific Coast Highway he rerouted. The California Highway Patrol accomplished this within 15 minutes of the request.

- He used the apparatus public address system to order bystanders out of the area and then requested response by Ventura County Sheriff’s officers for evacuation of the nearby beach campgrounds and residential areas.

- 1 le requested a haz-mat response to the incident. The Ventura County Hazardous Incident Response Team (H1RT), on another call at the time, was dispatched to the scene. The request also set into motion “automatic” notification of a variety of public and private agencies by emergency communications center personnel as part of SOPs for haz-mat calls.

- He established an initial safety perimeter on Pacific Coast Highway

- north of the accident.

- He used binoculars to inspect the wreckage for placards. None were visible. Cargo information was obtained from train personnel, from which it was ascertained that numerous hazardous materials were in the shipment.

UNIFIED INCIDENT COMMAND

A command post was established approximately 500 yards south of the incident on Pacific Coast Highway, a location that satisfied access, logistical, and personnel evacuation concerns. The unified incident command system was implemented. Command initiatives prior to arrival of haz-mat personnel focused on isolation, resident evacuation, and entry denial. Southern Pacific Railroad was contacted and a field representative requested to the scene.

At 1300 hours HIRT arrived, and Battalion Chief Darrell Ralston, incident commander, assigned the team the role of haz-mat group, which within the FIRESCOPE Incident Command System is responsible for activities related to haz-mat stabilization and mitigation and which makes strategic and tactical recommendations to the incident commander.

HIRT’s first step was to develop group objectives through an initial incident action plan. The plan’s primary objectives were to

- make a hazard assessment;

- determine if exclusion and evacuation areas were adequate;

- establish containment, reduction, and support zones;

- establish site access control; and

- determine the need for additional resources.

The positions of haz-mat safety officer, entry team leader, decon team leader, and technical reference specialists were assigned by team leader Captain Mike Proett. Proett’s initial visual scene assessment concluded that the command post location was appropriate and afforded an excellent buffer zone from which to conduct haz-mat support operations. The weather forecast for the next several days was favorable: A high-pressure system would remain in the area and winds would not be a factor. (The weather forecast was updated continually throughout the incident.)

HAZARD ASSESSMENT/IDENTIFICATION

The train’s shipping papers indicated that a total of 13 hazardous materials were among the cargo. A helicopter was requested and personnel from the haz-mat group performed an aerial hazard assessment. Since a major part of the wreckage was directly under the freeway overpass, identification of materials from the air was impossible. However, the team was able to determine that 14 cars were involved and that the majority of these were 90foot flat cars carrying land-sea containers (large metal boxes similar in size to a semi-truck); that containers and contents were scattered across the railroad right-of-way and Pacific Coast Highway, and that a large whitevapor cloud appeared to be coming from the area of a spilled white granular material and several damaged 55gallon drums.

By narrowing the number of cars involved to 14, the haz-mat group was able to use shipping papers and car identification numbers to reduce the list of materials from 13 to six, as follows:

Dichlorodifluoromethane (chemical formula), a nonflammable gas shipped as a liquid. Its primary hazard is to the environment and as an asphyxiant.

Chlorinated phenol (chemical formula), a Class B poison, toxic byinhalation and absorption, which may give off combustible vapors.

Combustible liquid, N.O.S., which is the proper shipping name for materials that have a flash point of between 100°F and 199°F but are not otherwise listed by the U.S. Department of Transportation.

Flammable liquids, paints, lacquers, and shellacs; and flammable liquids, adhesives and glues. (The hazards are the same for both, with flash points below 100°F.)

Hydrazine (51.2 percent solution), a combustible, oily, fuming liquid that is a reducing agent; reacts violently with oxidizers; is toxic by ingestion, inhalation, and skin contact; and is moderately corrosive. Though its flash point is 100°F, classifying it technically as a combustible liquid, in the presence of some materials its ignition temperature may be lower than 100°F. Its TLV-TWA is 0.1 ppm and its IDHI. is 80 ppm. (For a more complete description, see “Chemical Data Notebook Series #70: Hydrazine,” Hazardous Materials, Fire Engineering, March 1992.)

The shipper was contacted immediately, and within minutes a detailed MSDS arrived via fax machine to the scene.

MEDIA ARRIVAL

Within hours of the derailment, the news media converged on the incident in large numbers, presenting a challenge for personnel involved with scene security and information exchange. ‘Hie department’s information unit is an integral part of the command structure, and the public information function at this incident took on the qualities of a unified group. Information officers from the fire department, sheriffs office, and California Highway Patrol worked in concert with other participating agencies at the command post to provide hourly media briefings. A marked observation area was established for the media. They were permitted into this area during specific time periods as designated by the haz-mat group supervisor and were accompanied by an information officer at all times.

In spite of these efforts, at 1)15 hours, unknown to responders, a news reporter gained access into the exclusion area from the north side of the incident and exposed himself to materials from the accident scene. He was able to leave the accident area under his own power but complained of burning eyes, skin, and throat. After a field decontamination at Fire Station 25 (the north end of the incident), he was retrieved by properly protected decon personnel and returned to the designated contamination reduction zone for a complete decon and then transported to a local hospital.

ENTRY

Although aerial reconnaissance had proved successful to a degree, the haz-mat group still was faced with the task of identifying the containers and spilled product that had separated from their containers. Since regulations do not stipulate that individual containers or intermodal containers be cross-referenced by 11) number to their original rail cars —and because wreckage was extensive—positive identification of the products involved would require a detailed sitesurvey on foot and samples analyses.

At 1500 hours, with decon stations and haz-mat support/logistics established. an updated incident action plan was implemented. This called for two Level A reconnaissance entries, to include taking pictures/video footage; collecting samples for analysis; and providing command with a verbal description of the incident site, including positions of the cars, placards, labels, and container sizes and shapes. Hie City of Ventura Haz-Mat Team was requested and was integrated into the incident haz-mat group. With both teams working together, Level A entries were made in a timely fashion.

The recons produced vital information;

The white granular material was polyurethane beads.

Hydrazine (51.2 percent) was the primary product involved, leaking from 55-gallon drums. The visible cloud was being formed by its mixture with organic material (soil, etc ).

It did not appear that other products involved in the wreck had been released.

With knowledge of the product involved and its attendant hazards, the incident at this point was determined to be stable—it posed no immediate threat to life, environment, or property outside the exclusion zone—and, barring complications, essentially would be a neutralization/cleanup operation.

Southern Pacific Railroad’s hazardous-materials representative arrived on the scene at 2200 hours. After a briefing by the haz-mat group supervisor, he made, with fire personnel backup, a Level A entry. This entryconcurred with the haz-mat group conclusions.

(Photo by Jack Hughes.)

Southern Pacific accepted the responsibility for cleanup of the product and the damaged railcars and containers and requested a cleanup contractor to the incident. It was agreed that the haz-mat group would maintain site access control, scene safety, rescue backup, entry team leadership, and decontamination responsibilities. Control would remain with the original unified command, which had begun with the fire department, sheriffs office, and highway patrol and by this time included county environmental health agencies. Serving in an advisory capacity were medical agencies; the U.S. Coast Guard, since the accident occurred approximately 200 feet from its area of responsibil y; CalTrans engineers, because of r tential damage to freeway stanchi is; and local gas company represeni tives, because a potential breach ir large, natural-gas transmission line; unning under the scene was a primary concern.

(Photo courtesy of Ventura County Fire Department.)

(Photo by R. Ranger Dorn.)

The incident plan was updated at 0030 hours the following morning. A contractor employed by the railroad was to enter the spill site in proper protection and neutralize the spilled hydrazine with a calcium hypochlorite (swimming pool chlorine) solution, after which the damaged drums would be pumped off and overpacked along with all of the undamaged drums. From reconnaissance information it was believed that approximately 12 or 13 53-gallon drums were involved.

Assistant Chief Jim Smith, incident commander, ordered 1’/2-inch handheld hoselines to be staffed in the hot zone to protect workers. This required 1,500 feet of three-inch hose to be laid from a pumper to the wreckage area by firefighters in Level A protection. The hoselines then were staffed in coordination with worker entries.

NEUTRALIZATION AND CLEANUP

To accomplish the neutralization, 3,000 pounds of calcium hypochlorite was delivered to the scene. This would be mixed with water in two commercial water tankers (each with a 500to 600-gallon tank and pump) to create an eight-percent solution that would be sprayed onto the hydrazine. Since the reaction between the two products would produce hydrogen, ammonium, and chlorine gas, the importance of proper protective equipment and protective lines was underscored.

Both the water trucks and calcium hypochlorite shipment arrived by 1000 hours. Prior to proceeding with the neutralization procedure, command ordered another entry to determine the optimum position for the water trucks. During this entry , the team noted large quantities of hydrazine still in the damaged drums. Neutralization was delayed because a violent exothermic reaction would have occurred if the neutralizing solution entered the drums. A decision was made to pump off the damaged drums into a vacuum truck before overpacking and ground neutralization. (See “Field Transfers: Drums” on page 66.) From further scene analysis, it was determined that the actual number of hydrazine drums was close to 50.

A vacuum truck with a stainless steel tank was requested for the pump-off operation. The operation was delayed, however, because the truck that arrived had a carbon steel tank; the hydrazine would have reacted violently with iron oxide or similar contaminants. The proper vehicle arrived two hours later and transfer operations commenced.

Following are highlights of the operation, which continued for three more days:

Tuesday, July JO, 1991 00:22 Vacuum hose is not long enough to reach from the pump truck to the damaged drums. Truck is relocated to another position.

02:16 Cleanup contractor has underestimated the magnitude of the cleanup. Requests meeting with incident commander and Southern Pacific Railroad representatives. Operations put on hold until 0800 hours.

08:30 General staff meeting.

I 2:00 Planning meeting held, with the following control objectives restated:

(1) Pump off contents with dip tube.

(2) Neutralize contaminated areas with second entry team when pumpoff is completed. (3) Continue monitoring neutralization process. Further review by cleanup/industry representatives determines that eight damaged hydrazine drums will be pumped off. and the remainder overpacked.

1 5:00 Pump-off is completed. Fourteen cars still on the track are moved from the site. It is anticipated that neutralization will he applied shortly and by 1800 hours overpacking will commence.

16:52 Three illegal aliens are spotted in the exclusion zone. All are decontaminated and kept in custody. Their means of entry is unknown.

19:00 Neutralization begins. Wednesday, July J/, 1991 0 i 00 Incident action plan updated. Overpacking in Level B protection estimated to begin at 0800 hours and take 20 hours to conclude.

1 t ()0 Neutralizing agent has been safely applied. Fifty to 60 remaining drums are identified. A thorough physical examination of those drums reveals no evidence of leaks, and overpacking will commence in Level C protection.

23:35 Forty-one drums have been overpacked. Twelve remain. Thursday. August I, 1991 02:00 Overpacking is discontinued because six drums are discovered jammed inside a container. All are vacuumed prior to removal.

08:30 The 101 Freeway cannot be reopened until the following have occurred: (Da 6,000-gallon tank containing napthalene (a combustible liquid) resting against a freew ay support is removed, (2) engineers have inspected the bridge for structural damage, and (3) air and soil contamination have been confirmed by7 environmental authorities to be within acceptable levels.

09:45 There is a high level of contamination under the derailed cars. The neutralization process is continued. All personnel must be in Level B protection until further notice.

16:00 “Hot spot” areas of soil contamination are identified and isolated. The original isolation zone is reduced to a small area including the hot spots. With that reduction, the decon area accordingly is relocated closer to the work site. Workers are cleared to work in areas outside the hot spots in Level D protection.

17:30 Railroad personnel begin the process of removing the derailed cars. It is anticipated that the napthalene container will be removed by 1900 hours.

20:25 A crane moves a contaminated cargo container from the designation isolation zone into the Level I) work area. Operations are shut down as 11 railroad workers are exposed to a cloud of silica sand contaminated with hydrazine. Access control personnel witness the accident but are unable to stop it in time. As a result, a new site plan with tighter controls on cleanup personnel is put into effect. After definitive decon, nine of the 11 workers are transported to a local hospital for evaluation.

Friday. August 2, 1991 14:00 Operations are completed and scene safety is assured by all cooperating agencies. The freeway is reopened, and area residents are allowed back in their homes. All fire department personnel are released.

More than 20 agencies responded to the incident. At one point, haz-mat teams from six fire departments— with Ventura City, the South Coast team from Santa Barbara County, Los Angeles County, Kern County, and Oxnard responding in a mutual-aid capacity—staffed 36 positions.

LESSONS LEARNED AND REINFORCED

Among the lessons learned and reinforced from this incident are the following:

- The “go-get-it” mindset of structure firefighting has no place at a hazmat incident where public safety has been accounted for. Once the threat to civilian safety was addressed at this incident —by closing the freeway, evacuating residents, and securing the scene — time became a nonfactor relative to life safety of response personnel. Incident organization must provide adequate controls to ensure that all safety considerations are addressed. It literally may take hours to assemble the logistics and perform the tactics to accomplish one objective. Checks, double checks, and triple checks are preferable to alternatives in situations where one mistake can leave you no options to recover. Periodic reevaluation of incident action plans is essential, and input from every’ qualified team member is recommended.

Do not succumb to political pressure and compromise your safety protocols. With incidents involving major transportation arteries, in particular, “outside” parties with their own agendas may put strong pressure on you to speed up operations or take shortcuts. You also may experience a natural tendency to relax at a longterm incident. Remember: An incident can be just as dangerous in its last hours as it is in its first hour.

- A unified command structure and interagency cooperation and trust are necessary for a safe and successful resolution to a large-scale haz-mat incident. Without them, command and control —and safety — fall to pieces. A “hands-off” management style is required —no person can expect to remain awake and effective for the duration of a four-day incident. Confidence in the unified command system and in its players—reinforced by multiple-agency drills—made for smooth transitions of personnel and smooth integration of outside agencies into operational flow.

- Initial response actions are critical in averting disasters. First-in fire personnel at this incident played a key’ role in minimizing public exposure and setting the stage for a careful, safe, and successful operation. All mem-

- bers who respond to haz-mat or potential haz-mat incidents must be trained at the minimum to federal/ state OSHA regulations (29 CFR 1910.120 |q|). Training to NFPA 472 is highly recommended.

- Once immediate life hazards are addressed and the incident stabilized, the fire department should defer cleanup operations to specialized, responsible groups whenever possible yet maintain its scene control/safety function and entry team leadership, be prepared to provide rescue assistance, provide scene protection, and perform decontamination procedures.

- Fatigue is a major factor at extended incidents. Our experience has shown that operational periods should be no longer than 12 hours for moderate to light work loads and no more than four hours for heavy work loads Well-rested replacement personnel — officers included—are essential to safety. A rehab station should be established at a location removed from the incident.

- Access control is extremely important and will require several check points with continuous attendance. In incidents covering a large area, access control can be difficult. Expect the curious to attempt their own entries. Establish decon facilities each in the incident in anticipation of this possibility.

- Identifying materials at transportation incidents can be a challenging task. Labels and car identification numbers will be hidden from view, shipping papers may not provide you with the detailed information you require, loads are mixed, and it may be difficult to connect ejected cargo with its car or container of origin. Shippers are not required to provide identification numbers that would allow responders to cross-reference individual containers and intermodal containers with their railcar. As a result of the Seacliff incident and other train incidents in California, state legislation has been introduced that would mandate the cross-referencing concept for cargo identification.

- If possible, begin the product identification/site assessment process with a low-risk method (for instance, by helicopter) and graduate from there.

- Require private cleanup contractors to submit a written plan and make sure that they are capable of implementing it and are following the plan strictly. Halt operations and revise plans as necessary.

- Plan ahead for the media. If you don’t accommodate them, they will accommodate themselves. Commandapproved media tours to a well-marked, well-secured observation area at regular intervals proved effective.

- Video is a valuable tool for gathering and documenting information and is easier to use than an instant camera for responders in Level A and Level B personal protection. Personnel at the command post could view the same image at the same time, which enhanced our ability to make careful decisions *