DELAYED ALARM AT CHEMICAL FIRE

HAZARDOUS MATERIALS

A warehouse employee detected fumes from a burning chemical in an area where 700 to 800 250-pound drums of sodium hydrosulfite, a textile bleach, had been stacked an hour earlier. But instead of calling the fire department, he went across the street to a restaurant and called his company’s main office. The owner of the company then drove six blocks to the warehouse with breathing apparatus. Heavier fumes were encountered, and dry chemical extinguishers obscured vision. Finally, a decision was made to call the fire department. This was done by walking back to the restaurant and calling the company office again. A secretary there dialed 911.

When the Charlotte, N.C., Fire Department got the 911 call to a chemical fire last Sept. 13 at 1611 hours —after about a 20-minute delay – it dispatched a box alarm assignment. Within two minutes. Engines 11,4 and 7, Ladder 4 and Battalion Chief Luther Fincher arrived to find gray smoke showing at the rear of the one-story brick structure. Fincher established command at the loading dock on the northeast side of the building. Because the secretary reporting the fire had identified the product involved as sodium hydrosulfate, the fire alarm center had relayed hazardous materials data to the responding companies.

The companies were informed that sodium hydrosulfite is water reactive – that dry chemical, carbon dioxide or sand are the best extinguishing agents and that water should not be used unless flooding amounts could be applied. Personnel were informed that SCBA should be worn for protection from sulfur dioxide and hydrogen sulfide released in the combustion process. These products combine with moisture of the skin, mouth, eyes and nasal passages to form sulfuric acid.

In sizing up the situation, Fincher confirmed that a drum of sodium hydrosulfite was smoldering. (Fire investigators later learned that it had been damaged, exposing the chemical to moisture in the air.) Now employees wearing SCBA were attempting to move 1000-pound pallets of sodium hydrosulfite. These pallets were stacked to the ceiling. A forklift truck was being used to gain access to the smoldering drum.

Fincher ordered Engine 11, Engine 7 and part of Engine 4’s crew to report into the fire scene as Engine 4 stood by the hydrant in front of the building. Fire fighters entered the warehouse with dry chemical fire extinguishers in an attempt to prevent fire development, remove the hot drum from the building and isolate it from the other drums.

At 1618 Fincher was advised by crews inside the building that they could not locate the involved drum due to poor visibility and tightly stacked pallets with no aisles.

Exhaust fans were set up to remove fumes and dry chemical powder. Truck 7, a heavy rescue vehicle with additional large fans, generator, lights and air cascade, was special-called. Efforts continued to remove the drum, but at 1624 Engine 4’s crew reported flames visible. This was quickly followed with a report that the fire had been extinguished. Fire alarm, overhearing the report, cautioned Engine 4 that the hazardous materials information indicated sodium hydrosulfite can reignite in the air. Engine 4 acknowledged the caution and reported that the product had, in fact, just reignited and that flames had been extinguished a second time with dry chemical.

Dry chemical extinguishers were used repeatedly to extinguish the fire which persistently reignited after each application. Fire fighters continued to work at removing other drums to get to the involved drum.

Second alarm, new tactics

Fincher ordered a second alarm at 1633 hours, because dry chemical and carbon dioxide extinguishers on the scene were depleted. Engines 1, 5 and 2, Platform 1 (an 85-foot aerial apparatus with articulating boom and basket), a hose tender, Squad 1 (a flying personnel squad) and Battalion Chief Roger Weaver responded with additional extinguishers. A special alarm followed for Blaze 7, a quick-response airport crash truck equipped with 450 pounds of dry chemical, but tactics had to be changed before it arrived.

By 1657 hours conditions had worsened to involvement of 15 or more drums. Flames from floor to ceiling became visible to crews working inside the structure. All personnel were ordered out of the building as drums began to rupture.

The offensive mode had to be changed to a defensive one. A high-volume attack was prepared.

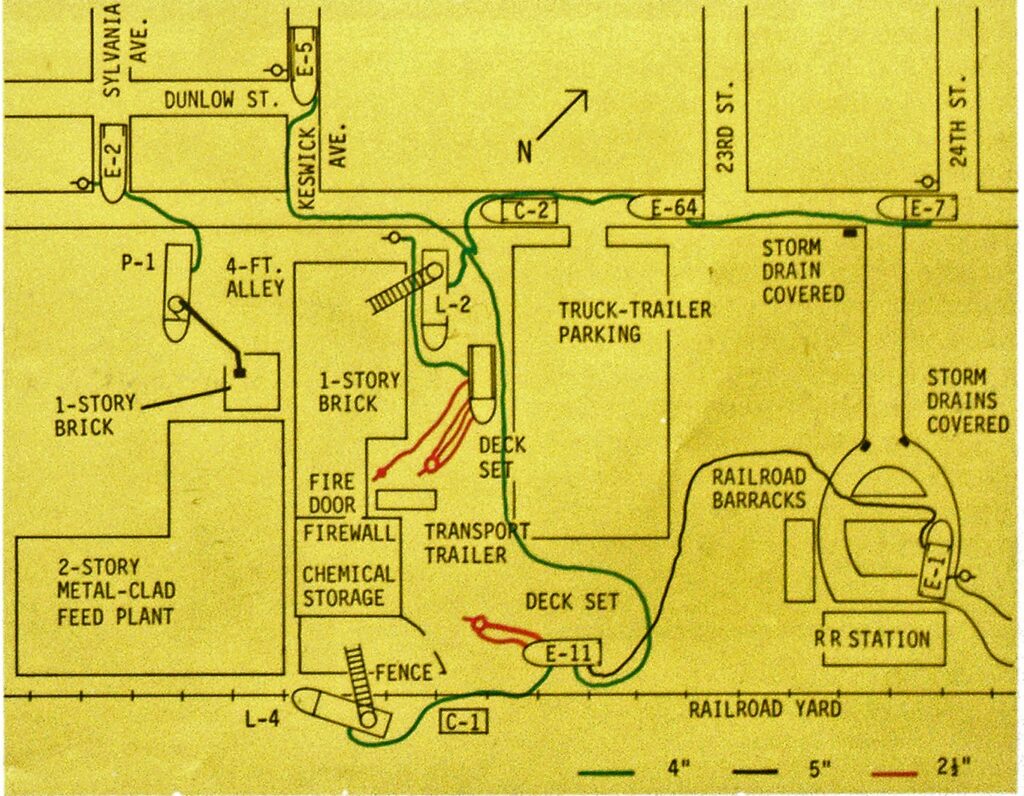

The door through the parapeted fire wall was closed to prevent extension to front areas of the warehouse. Engine 4, which now had a 2 ½-inch hand line laid to the loading dock for backup protection of personnel, set up a master stream appliance in this area supplied by three 2 ½inch lines. Rush-hour traffic was rerouted as Engine 11 made a forward lay of 4-inch supply line from the corner of Keswick Ave. and Dunlow St. to the rear of a trailer parking lot adjacent to the east corner of the warehouse. Engine 5 made a steamer connection and relay pumped.

Platform 1 was set up on the west corner of the warehouse, supplied through a 4inch line from Engine 2 at the corner of Sylvania Ave. and Tryon St. From this position the platform could protect the two-story, metal-dad offices of a neighboring feed processing plant separated from the fire by a 4-foot-wide alley. This protection was supplemented by an exterior sprinkler system on the side of the office structure.

A special alarm was ordered for Ladder 2, while Ladder 4 set up along the railroad tracks at the rear of the structure. It was supplied by a 4-inch line hand laid from Engine 11 through a fence and heavy brush.

As this operation was being set up, fire fighters, with the assistance of police, were evacuating the feed processing plant and railroad yard on either side of the warehouse. Acrid fumes were making these areas unsafe for persons without SCBA protection. Weaver, who had command of the rear of the building, reported brown smoke visible, indicating structural involvement.

Simultaneous deluge planned

Ladder 4 was instructed to begin dispersing vapors with the water tower stream but to avoid application of water to the fire building until other companies were ready to simultaneously deluge the sodium hydrosulfite.

Because drums were stacked tightly in a confined area that prohibited an interior attack, it was decided by Fincher, conferring with Assistant Chief R. L. Blackwelder who had arrived on the scene, that the only way to ensure a high volume attack in the right place was to let the roof burn away. This would allow master streams to simultaneously hit the seat of the fire and flood all the drums of chemical.

No one was sure how the sodium hydrosulfite would react or what amount of water would be adequate to flood such a large quantity of the chemical. Personnel were instructed to keep as much distance between themselves and the building as possible.

Paraquat discovered

Matters were complicated as fire fighters withdrew – retrieving a sample one-gallon plastic jug of liquid which Fire Marshal Art Goldner identified as paraquat. Chemical data on the herbicide could not be found in any of the hazardous material guides on the scene or at fire alarm. Not knowing its properties, officers used extra caution to keep fire fighters out of the smoke, even those wearing SCBA, until the manufacturer was contacted through CHEMTREC and verified that paraquat could not be absorbed through the skin. Fire alarm was advised that heating of paraquat releases carbon monoxide, toxic oxides of nitrogen and sulfur, and hydrogen chloride, which combines with moisture of the body to form hydrochloric acid.

In all, 3200 gallons of paraquat were present in the fire area. The company owner also told fire fighters about additional 800 cases of tobacco insecticide in the building.

All personnel exposed to smoke were ordered to operate with full protective clothing and SCBA and the command post was moved north on Tryon St. Later this position became untenable without SCBA, causing the command post to be moved farther along Tryon.

Engine 7 laid a 4-inch line from the hydrant at 24th St. and Tryon to Ladder 2 at the north corner of the building. By 1735 a large hole had burned in the roof. Companies were ready to flow water and personnel were instructed to position master stream nozzles and then withciraw in the event of an explosion. Fincher ordered the attack to begin.

Deluge tactic works

The booms of Ladder 4 and Platform 1 were turned from exposures to the fire itself. Engine 4’s throttle was advanced to supply the master stream appliance on the east side of the building. Engine 7 and Ladder 2 also revved up their pumps but a section of hose burst in the 1500-foot lay, putting Ladder 2 out of commission for several critical minutes.

[Continued on page 28)

(Continued from page 75)

Nevertheless, the deluge tactic worked. The main body of fire was controlled. Portions of the roof had collapsed, however, blocking fire streams from several hot spots, and drums continued to rupture.

To supplement Ladder 4’s water supply, the hose tender laid a 5-inch line from a hydrant at the railroad station to Engine 11, with Engine 1 relay pumping. This also enabled Engine 11 to pump into a master stream appliance at the rear corner of the warehouse.

Engine 7 continued to have bad luck. The burst section of hose was replaced and water flow resumed at 1744. But in two minutes a coupling blew apart, striking a fire fighter. Medical aid was administered as an additional engine was called to relay pump the line. Engine 64 was in position in 20 minutes.

When the fire first ventilated the roof, smoke rose above the ground on a thermal column, carried on a mild easterly breeze. The only threat of smoke inhalation was to personnel in the immediate area of the building.

This condition quickly changed. Shortly after the exterior attack began, wind direction changed 180 degrees and cool evening air settled to the ground, holding smoke down as it was pushed into the residential neighborhood west of the incident.

Immediate evacuation of the neighborhood was necessary. Four city buses were pressed into emergency service, transporting 600 to 800 residents to shelters.

At 1903 Blackwelder assumed overall command of the incident, with Fincher as fireground commander, assisted by Weaver in command of the east sector and Battalion Chief Bill Summers (who had reported from off duty) in command of the south sector.

Wind direction fluctuated in the next two hours. With smoke continuing to push west and north at ground level, the evacuation area was expanded several times. The city department of transportation altered the traffic signal computer program to expedite evacuation from the area.

There was a heavy demand for breathing air throughout the night. Not only were fire fighters heavily dependent upon air bottles (some 30-minute tanks were refilled 15 to 20 times) but police officers responsible for evacuation were given quick lessons on the scene in the use of SCBA by the fire department training division.

Truck 7’s air cascade system was supplemented by cascade systems and extra SCBA brought to the scene by the Charlotte Life Saving Volunteer Rescue Squad and nine volunteer fire departments from Derita, Hickory Grove, Mallard Creek, Mint Hill, Newell, Pineville, Pinoca, Statesville Road and Steele Creek. Cascade cylinders were shuttled between the fire scene and the fire department supply division for refilling. In all, more than 50 300-cubic-foot air cylinders were used.

After flowing an estimated 4000 gpm for an hour and a half to cool reacting sodium hydrosulfite, master streams were shut down. Engine 11 stretched 1 ½ -inch hand lines to the rear overhead door. The frame of the door was removed with the help of a winch on Brush 22, and fire fighters began the tedious overhaul process of removing what remained of the sodium hydrosulfite drums one at a time, flooding each with water. A front-end loader was brought to the scene to assist in the removal and to build a dike around the loading dock for containment of the chemicals.

Even as this operation was beginning, a drum ruptured. Fire fighters proceeded with caution, still wearing full protective clothing and SCBA. Overhaul continued well into the next day.

Environmental officials, automatically notified by fire alarm after arrival of the first equipment, anticipated a problem with contaminated water runoff from the fire scene. Salvage covers were placed over storm drains downhill from the fire scene in front of the railroad station to prevent runoff into the drains. These tarpaulins were held in place by sand hauled to the scene by the street maintenance department.

The method worked. Forty thousand gallons of paraquat-contaminated water were contained and later hauled away for disposal.

Unfortunately the reservoir created by the blocked drains was insufficient to control all the runoff. Officials discovered that paraquat was entering Little Sugar Creek, which flows through the watershed several blocks northeast of the fire scene. To control this runoff, two earthen dams were constructed using sand trucks and a backhoe. The next day a third dam was constructed.

Photo by Elmer Horton, The Charlotte News

Following much concern over contamination of drinking water supplies downstream in South Carolina, environmental officials took a calculated risk, systematically opening the dams four days later. The calculations proved accurate and paraquat was diluted to safe levels as the creek mixed with the Catawba River before reaching water treatment plants.

Five fire fighters suffered injuries including smoke inhalation, bruised ribs, a facial laceration and contusion of an ankle. Over the next several days, 61 fire fighters suffering sore throats, skin rashes and flulike symptoms were checked by the city employee medical services. Blood and urine samples were collected from 109 fire fighters for laboratory analysis to determine the extent of medical problems. No one is sure what the long-term medical effects of this incident will be.

Most of the first and second-alarm Cshift personnel were relieved at 1800 hours when A-shift came on duty. As prolonged operations continued, these personnel, wearing SCBA and protective clothing, were under considerable strain. Beginning at 2300 hours, engine companies from outlying stations were called to the fire scene, and their crews switched with engine companies committed to the fire. Crews from Engines 6, 18,8, 22,15 and 21 were matched with apparatus similar to theirs to minimize unfamiliarity. Relieved crews were returned to the outlying stations with the uncommitted apparatus.

Because each of the three pieces of aerial apparatus in use was unique, only the crews assigned to those apparatus were considered knowledgeable enough to safely operate them. These crews were transported to their respective fire stations for showers and a change of clothing, then returned to the scene for the remainder of the night.

At 0448 the next morning, the incident was declared under control. At 0530 hours evacuated residents were permitted to return to their homes. They were instructed by health officials to discard any food that had been exposed to smoke.

The chemical company hired a chemical salvage contractor to clean up the warehouse site under the supervision of the environmental health department and the regional EPA office.

The last engine company cleared the scene on Wednesday at 1630, although sodium hydrosulfite continued to smolder for another 24 hours.

This incident identified a weak point in our fire inspection program. The fire prevention bureau had ordered correction of fire and building code violations at the warehouse before the incident occurred. Violations included storage of chemicals without a fire department permit, failure to adequately separate the chemicals, pallets stacked too high, no aisles provided between pallets, failure to post 704M warning placards on the exterior of the warehouse (see “Entire Buildings Are Labeled With NFPA 704M Marking System,” Fire Engineering, September 1982), and a storage of these chemicals in an unsprinklered building.

Because the owner had been ordered to remove the chemicals, their presence was not updated on the building record form for the warehouse that is kept on file at fire alarm. Placards that normally identify hazards present at chemical incidents were not displayed either. Had the chemicals been stored in compliance, their presence and basic properties would have been recorded on the building record and posted in the form of 704M placards.

Proper storage of the sodium hydrosulfite with wide aisles and restricted height of pallets would have made locating and isolating the damaged drum much easier. A sprinkler system could have provided the flooding quantities of water in the proper place to cool exposed drums.

The incident is causing code enforcement policies within the department to be tightened up to allow less time for correction of violations and prompt legal action for noncompliance. At this writing the city is pressing legal action against the chemical company.