The run came in around 2 a.m., a time in the Bronx that often indicated the likelihood of a life-threatening fire. However, this middle-of-the-night response would prove to be an entirely different affair. The dispatcher informed us that we were being assigned to investigate a report of an overcrowded nightclub.

- What If…? Using Your Imagination in Fireground Strategy

- The Command Bubble: A Tool for the Fireground and For Life

- Thinking Like an Incident Commander

- Evaluating the Human Factor on the Fireground

We arrived on scene in just a few minutes and, with a great deal of effort, began to slowly work our way into the club. Once inside, we encountered an overwhelming and physically challenging environment. People were literally packed wall to wall amidst a backdrop of pounding music. It was a challenge to move at all, much less locate and communicate with the club manager, and it looked like things were going to get even worse.

Outside the building, there was a long line of people also trying to work their way in. There was a clear sense that anything—a whiff of smoke, an unexpected loud noise, or even a sudden surge of crowd movement—could have immediate and disastrous effects. My firefighters were very experienced and well acquainted with the chaotic and challenging initial moments of a firefight, but this was a very different and intimidating experience. We were all feeling very much on edge as we elbowed our way farther and farther into the mass of bodies.

A Deadly History

Unfortunately, there is a long and lethal precedent of crowd disasters, and they have occurred at a variety of events. Most recently, 158 people were killed at a crowded Halloween event in Seoul, Korea. In 2021, 45 deaths occurred at a religious festival in Israel. A 1989 incident at a soccer stadium in England led to 97 deaths and hundreds of injuries. More than 2,400 died at one of the worst catastrophes in history when crowds surged at a Hajj pilgrimage in Saudi Arabia in 2015.

The tragedies have not been limited to international events. The United States has its own history of incidents. Ten were killed and hundreds injured at a 2021 music event in Houston. A 2003 stampede in a Chicago nightclub led to 21 deaths, and eight were killed at a 1991 celebrity basketball game in Manhattan. The problem is universal human behavior, and the potential for deaths and injuries from crowd-related incidents is not limited to any one culture or nation.

How It Occurs

Music and sports events typically position large crowds of people in congested spaces. However, there are common elements at play in crowd disasters regardless of the nature of the gathering. The density of the crowd is the key factor rather than the number of people in attendance. People are generally not trampled; they die from asphyxiation. The pressure exerted on their lungs prevents them from getting enough oxygen. It is estimated that when more than five people have congregated in an area the size of a square meter (approximately 11 square feet), they face a potentially dangerous situation.

At that point, the “crowd quake” phenomenon can take effect. The area becomes so congested that even a slight movement of a few individuals can initiate a damaging turbulent pressure wave that moves through the entire crowd.

The concept of “group think” can also influence crowd behavior—a situation where some individuals initiate an action like suddenly surging forward with the rest of the crowd following their behavior. With these points in mind, a quick size-up of the gathering in photo 1 indicates a far greater potential hazard than the one in photo 2.

(1) Photo by Tijs van Leur. https://unsplash.com/@tijsvl.

(2) Photo by Uwe Conrad. http://uweconrad.ch/dev/.

Contributing Factors

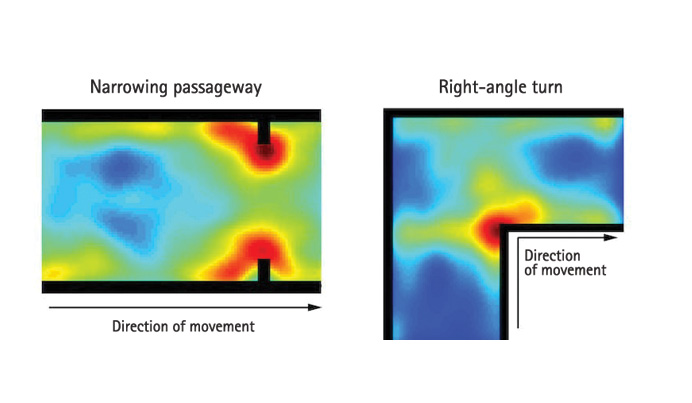

- Physical constrictions. Any walls, barricades, or passageways that might limit the free movement of a large congregation of people can create issues. Tight alleyways in particular will be dangerous (photo 3). At the Seoul, Korea, incident, many people were crushed and died in an alley that was 130 feet long and only 10 feet wide. Passageways that have physical restrictions or turns in them present dangers. The red-colored areas in Figure 1 represent choke points and highlight particularly hazardous areas.

(3) Photo by Xavi Cabrera. https://unsplash.com/@xavi_cabrera.

Figure 1. Passageway Hazardous Choke Points

Source: The Conversation, “Ten Tips for Surviving a Crowd Crush.” https://bit.ly/3ztQegZ.

- Topography. Hilly areas can restrict and slow down overall crowd movement and contribute to the potential danger. The alleyway in Seoul that caused so much damage was on a slope.

- Lack of supervision. An insufficient number of emergency personnel specifically tasked to crowd control is a common theme in these disasters. It is estimated that 100,000 people attended the Seoul event and only 137 police officers were assigned, many of whom were there for crime prevention rather than crowd supervision. The National Fire Protection Association recommends a ratio of one trained crowd manager per 250 people for most assembly occupancies.

- Spontaneous events. A quickly assembled, unplanned gathering such as a protest or demonstration can create issues. Such incidents may not have clearly defined sponsors or organizers available to address any safety concerns that may arise.

- Lack of planning. Although spontaneous incidents are unpredictable, any scheduled large-scale event should mandate a plan to address potential crowd dangers. Poor or nonexistent planning has been an avoidable but a consistent contributing factor at past disasters.

Crowd Management Strategies

Complete a life safety evaluation prior to any large-scale event with the potential to draw a large number of attendees. Perform a physical crowd-management size-up of the site just as you would evaluate a building for firefighting concerns in a prefire inspection. Consider the following:

- Physical layout. Does the topography present any possible crowd flow bottlenecks? Are egress routes adequate? Can you quickly establish access for any required medical or fire responses?

- Anticipated number of attendees. Do you have a sufficient number of crowd managers available? Establish the means of transportation that attendees will use to arrive at the site and whether their movement may overwhelm the capacity of the transport facility.

- Communication. These events can involve personnel from different emergency response agencies. There should be an effective means of communication between them. If a crowd issue arises, police and fire personnel may both become heavily involved in the operation; their activities will have to be coordinated. If you need to move a group of people, that movement should be carefully controlled. The most effective way to accomplish this is to position radio-equipped members at both the front and rear of the group, which will allow them to slow down the movement as needed. Finally, you should have a line of communication with the event organizers and a means of broadcasting any vital information directly to the event attendees.

- The nature of the gathering. Is it a musical or political event? Will the emotional state of the attendees or possible drug or alcohol consumption affect their ability to react as needed if an emergency or a hazardous condition occurs?

- Education. Fatal crowd disasters are low-frequency/high-fatality incidents. When they do occur, they make a big splash in the news and then are quickly forgotten. Most people are well-versed in the basic fire safety lessons they learned from our fire prevention and education efforts. However, the same cannot be said of their knowledge of the potential dangers of overcrowding. The public should know that crowd density and any imminent danger can shift in seconds. Situational awareness is not just for emergency responders. Their awareness of what is happening around them can make the difference between survival and death. There are also some basic survival lessons that need to be reinforced. In a hazardous crowding situation, people should know that they should move with the flow of the crowd rather than oppose it and, if possible, try to move diagonally to the edge of the mass of people to increase their chances of survival.

Nothing of note happened in that middle-of-the-night response to that overcrowded Bronx nightclub, and that in itself is significant. The crowd was reduced to a safe level, the possible danger of a large group of bodies suddenly and dangerously massing together was eliminated, and the potential for deaths and severe injuries was also eliminated. We walked away with a lesson reinforced about the challenges of our profession.

The fire service is well acclimated to the task of using tools, equipment, and procedures to extinguish fires. However, we are also in the business of managing people, and the task of safely evacuating and moving groups of them is one of our most important responsibilities.

Following the Seoul disaster, the Korean Ministry of Interior and Safety stated that it had “no guidelines or a manual for such an unprecedented situation,” an evaluation that is probably not unique to that agency. Perhaps a basic knowledge of human behavior and crowd dynamics is a good step toward preventing future disasters.

References

Bigda, Kristin. (May 20, 2021) Strategies for Crowd Management Safety. NFPA Today. https://bit.ly/3Kc7Yn1. https://bit.ly/3Kc7Yn1.

Cavanagh, Niamh. (November 2, 2022) South Korea Halloween Stampede: Why do crowd crushes happen and how can they be prevented? Yahoo! News. https://yhoo.it/3lIDzDv.

CNN.com. (November 1, 2022) South Korean authorities say they had no guidelines for Halloween crowds as families grieve victims. https://cnn.it/3JO7li7.

Moussaid, Mehdi. (February 17, 2019) Ten tips for surviving a crowd crush. The Conversation. https://bit.ly/3ztQegZ.

Pope, Tara Parker. (October 31, 2022) How to survive a crowd crush and why they can become deadly. Washingtonpost.com. https://bit.ly/3zaN6pX.

Sang-Hun, Choe. (November 1, 2022) Few Officers and No Crowd Control Plan on Night 150 Died in Seoul. The New York Times, International Section.

THOMAS DUNNE is a retired deputy chief and a 33-year veteran of the Fire Department of New York (FDNY) with extensive experience working in midtown Manhattan and the Bronx. He has written numerous articles for Fire Engineering and lectures on a variety of fire service topics. He is the author of the FDNY memoir Notes from the Fireground and the novel A Moment in Time.