By THOMAS E. POULIN

Fire/emergency medical services (EMS) organizations and their members wish to provide the best services possible to their communities. They take great pride in the quality of their services, with most seeking to provide more effective and efficient services that continuously meet the changes of a dynamic environment. Meeting this challenge requires that fire/EMS agencies objectively assess their performance, identifying means of leveraging their strengths and addressing any weak areas. An effective critique process can support this, but we must ensure that we do not shift from a critique to a “crittack” (explained later in the article) to a travelogue.

Critiques: Continuous Improvement

A critique is an objective, professional, collaborative function taken to assess an activity. The focus is on making that activity, or similar activities, more effective and efficient over time. During a critique, we should consider what we observed, what we did, how well it worked, and how it might be done better. Remember, the goal of a critique is not necessarily about fixing something broken; it can be about making something strong even stronger.

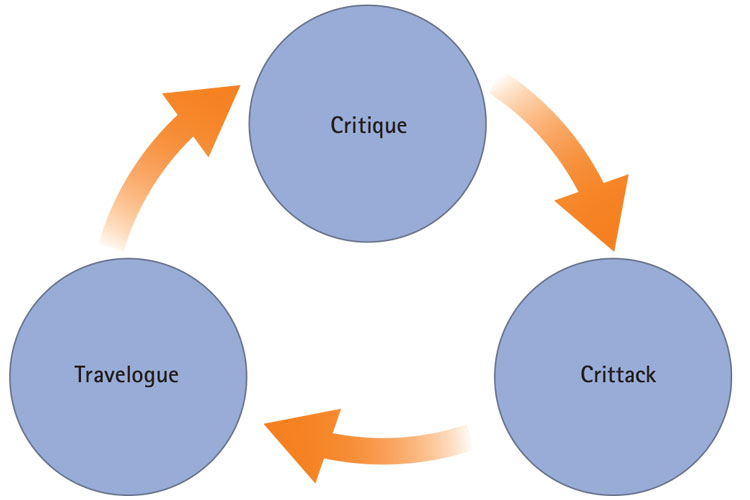

Continuous process improvement is about incremental change and making small refinements to our efforts that might seem minor at the time but whose cumulative effects can be dramatic. In the Japanese industry, this concept is described as Kaizen – the goal of doing something a little bit better every time we do it. Done properly, critiques can be valuable learning tools for fire/EMS agencies, ensuring continuous improvement, but we must monitor ourselves to ensure that we do not shift into unproductive shadows of the critique cycle (Figure 1).

Crittacks: Organizational Scapegoating

A crittack is a critique morphed by negative attitudes. Commonly, the process began as a critique, but something during that process changed. The focus is no longer on improvements but on focusing blame. Crittacks may develop when an incident has gone poorly or when the organizational culture has become toxic. In the former, we might find a significant event that is under strict scrutiny by the public, regulatory agencies, the media, the courts, or a combination of all four. In the latter, the organizational culture has become toxic, with powerful cliques emerging. In such a setting, some members cannot or will not be held accountable by organizational leadership. In such circumstances, it is possible for the crittack to focus on self-protection or the protection of the organization. We might all agree that this is not a productive situation and that it should not occur, but most members in fire/EMS have seen something like this occur in their organization or neighboring ones. The aftermath of the incident is marked by tension and anxiety. Some may focus on specific actions by one individual or one crew, trying to lay all the fault at their door which may, in turn, protect all others.

If a crittack does emerge, the focus is more on protecting reputations than on improving services; once a scapegoat is identified, the matter is closed. This can have a negative impact on individuals and the agency, and it might inhibit open communications in the future, which is why we will often see a period of crittacks followed by a period of travelogues.

Travelogues: The Stalled Organization

If communications begin to falter, a critique may turn into a travelogue. A travelogue is an agreement of what happened – who did what and when it was done. These are important facts, but if they are the sole facts developed, they are largely without value. A travelogue may be viewed as an attempt to comply with expectations on an incident that will then be deconstructed; that is all. There is no in-depth analysis or evaluation of the activity, no statement of what was and was not done well or how it might be improved. It is as if the unstated goal was to avoid any open debate, and those running the process now fear that a crittack may start developing.

To accomplish this, we must not discuss anything that might be considered offensive to others or permit others to do so. Travelogues tend to be bland, uninformative, and useless to the organization in terms of process improvement. However, they do serve a useful short-term function in organizational transitions, helping people to be in the same room together in a peaceful manner. They may not be speaking substantively, but at least they are being civil – no longer attacking one another. A travelogue helps to bring stability back to discussions, setting the foundation for the organization to shift back to the idealized form of critique. This shift back will take leadership, and that leadership can emerge from any level of the organization.

Guidelines

It might be a generalization, but we can safely presume that everyone in fire/EMS wishes to do the best they can and that they take great pride in their performance. They would like to improve over time, and a strong critique process can help to support those goals which, aside from supporting the needs of individuals, will also serve the needs and expectations of the community. To provide for a more effective critique process, the following guidelines may help.

Use standards as a framework. Organizations should adopt standardized practices and base training on those standards. Any activity assessment should compare best practices to those standards. In other words, train the way you wish to act, act like you were trained, and then assess your work by comparing training to performance.

Be flexible. Although an organization must base critiques on standards, it must recognize that the critiques will not apply to all settings. Therefore, we need to be somewhat flexible in our assessments by using the standard of reasonableness. For example, when a company officer is deciding to go offensive or defensive on a fire, we need to consider what the typical company officer might do in the same situation based on what he could observe and what he might reasonably have been expected to know when making decisions or undertaking a task.

Work from the bottom up. Once you have gathered the facts, start the evaluation – the assessment of strengths, weaknesses, and areas of potential improvement – from the bottom up. If the senior officers speak first, lower-ranking personnel may be hesitant to share their thoughts. This limits the process, and it does not help develop those lower-ranking personnel.

Instead of starting at the top, start the critique at the bottom. Treat any comments with respect, recognizing the strong points made by lower-ranking personnel and clarifying or correcting any incorrect points as needed. Approaching the evaluation like this will do several things. First, it gets lower-ranking personnel engaged, bringing in relevant views concerning the task level of operations. Even if higher-ranking officers have substantial experience, they are now removed from that task level. Get the views of those who will actually do the work. Second, it facilitates the development of the decision-making skills of lower-ranking personnel, helping them develop in several ways that will support stronger performance not only in their current position but in any future organizational roles they may play. Third, it provides objectivity to the overall process by bringing in new perspectives (which I will discuss in the next section on objectivity). Last, it builds relationships throughout the organization – relationships that support mutual trust and respect that can have several benefits to the organization, short- and long-term. Teams need to have a sense that they are a team. Engaging in relationship-building activities helps to develop that sense of team. Working from the bottom up helps foster a team-based approach to critiques.

Ensure objectivity. In most organizations, the incident commander (IC) conducts the critique. This means the individual who is legally, ethically, and morally responsible for the outcome of a response is assessing his own work. Taken at face value, this may be problematic; ICs may be too close and, in some instances, too concerned with protecting their status to evaluate their work objectively. This is not necessarily going to be the case, but it is something that organizations should consider. This might be of greater concern with a significant event such as those associated with the development of a crittack.

To address these concerns, consider using a process similar to the military’s after an aircraft crashes. The officers from the unit – including any surviving flight crew – play a limited role in the process. Instead, the military brings in flight instructors, pilots, aircraft designers, mechanics, and safety personnel, among others. These actors will explore the event from a wholly objective perspective, providing greater clarity into the events.

Fire/EMS agencies might consider something like this, whether it means using a facilitator (someone from within the organization but who was not on the scene) to ensure all views are considered appropriately or bringing in people from other fire/EMS agencies, letting them make an assessment and then sharing their findings with the agency chief. This latter approach, being less traditional, will involve more risk. It will also require true leadership to instigate this approach and accept the findings, but it is not a wholly unknown approach in the fire/EMS community. In the past, such an approach was used in large-scale incidents such as the Charleston Sofa Superstore Fire, which can contribute to more objective findings and which might, in turn, spur improvements in the process. In the end, this should be the goal of a critique.

Use the findings. One of the greatest weaknesses of many critiques is that the findings are not shared, even if the process was powerful in identifying potential improvements. This means that those not actually present will not benefit from the experiences of their own organization, which limits the utility of the process.

The findings of a critique should be shared with others in the organization. They should be used to change policy, training, and operations as necessary. This point seems so obvious that it can be overlooked, but a critique process that is not used to validate current practices or improve future practices is meaningless. Ideally, the findings may be shared outside the agency, letting other fire/EMS agencies learn from your experiences. In this way, the entire discipline can improve, providing a stronger response capacity nationwide and helping us avoid the painful process others might have gone through to garner these lessons.

Developing a New Mindset

An interesting example of a critique involves the musician Prince. At the height of Prince’s career, someone from the music industry was asked if he wished to join Prince after a show. Thinking this would lead to a series of parties, the invitee accepted, only to find that the time after the show was devoted to watching recordings of the very show from earlier that evening. Watching these recordings, Prince and his band critically dissected the performance in terms of music, movement, and presentation. The guest asked why, given their outstanding performance, they would worry about this. Prince’s response, while pointing at the recorded images, was that the band wanted to be better than that.

This is the type of mindset that leads to high quality, to excellence. It is a mindset that would serve everyone – the individual, the fire/EMS agency, and the community – very well.

THOMAS E. POULIN, PhD, serves on Capella University’s public administration faculty and teaches for the National Fire Academy’s Executive Fire Officer Program. He is a 30-plus-year fire service veteran.

THE CRITIQUE

The After-Action Review

A New Approach to After-Action Reports

Fire Engineering Archives