By Mike Norris

Most firefighters aspire to sit in the right seat someday in their careers. At least I did, as do most of the firefighters I know. However, when you are sitting on the officer’s side, and you are now the designated “leader,” it is much different than when you are “filling in” or “riding out.” Even if you do not aspire to leave the backstep, you desire to be the best version of yourself, especially on the fireground or rescue scene.

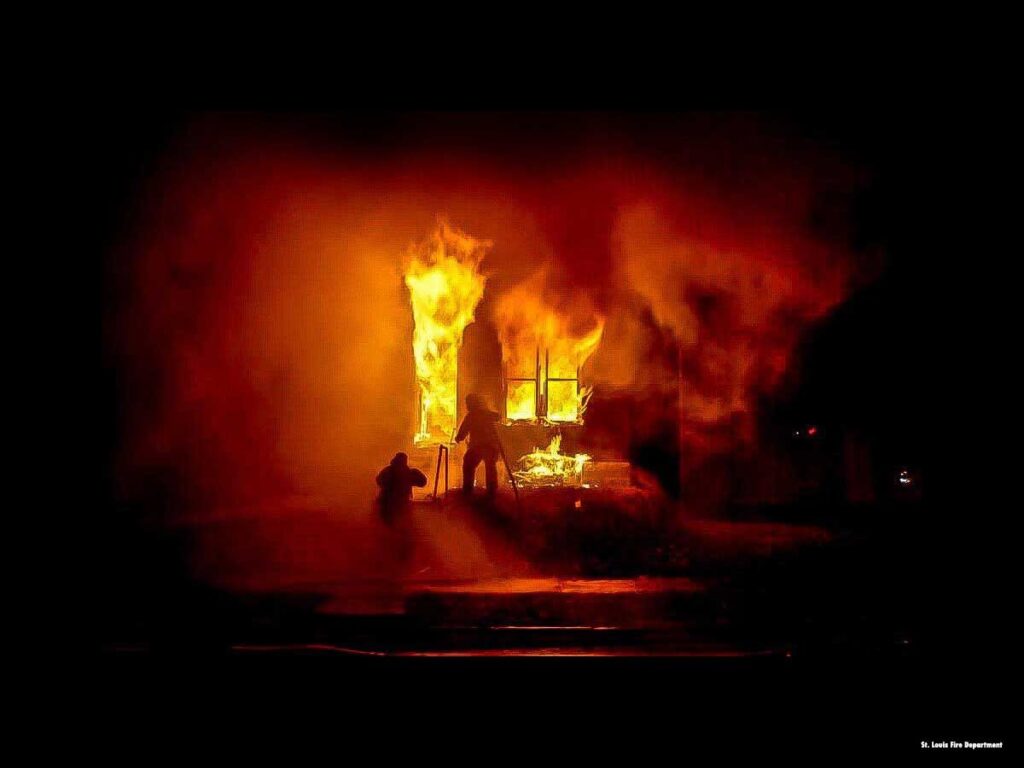

I vividly remember returning to my first fire as a newly promoted captain. Before that moment, I felt confident, prepared, and ready to lead. I remember seeing the smoke from the distance and knowing we were heading to a “good” fire. I vividly remember pulling up, smelling the fire, and observing it. When I pulled up on the scene, the house was well involved. Did we knock the fire down and stop it? Yes, we did. Were my crew and I aggressive and organized with our tactics on the fire? Yes, we were.

However, after analyzing my behavior, I realized that I could have handled myself better psychologically and with regard to my outward behavior. I recognized after the fact that I had to work on myself as a fire officer and a tactical leader, not physically, but psychologically.

Individuals must effectively lead themselves before they can effectively lead others. Does this mean that one must be perfect? It means the opposite. Recognizing and accepting your imperfections is what leads to growth. Growth in the fire service requires humility, knowledge, and experience. As a fire chief, fire officer, or backstep Firefighter, this is a crucial conversation you must have with yourself regularly. As difficult conversation leads to growth in your relationships, it also leads to growth when you analyze your path and thoughts.

How the Brain Responds to Stress

Controlled tactical aggression is a psychological approach I developed for the fire-rescue service. As my career progressed, I realized I would benefit from a new, more psychologically based and developed line of thinking. The core idea of controlled tactical aggression is that if the fire officer can control himself and his emotions, he can, in turn, control the chaos around him. Is it simple enough? Sure, in theory, it is when it’s quiet, and you think about the day before while in bed. The fantasy of controlling yourself seems plausible when you are not being pulled in five different directions when arriving on the scene of an emergency: the mother screaming to save her children, the neighbor saying that you took too long, and the person with a camera in your face just hoping you screw something up so they can be the next YouTube hero.

The Stress Tetrahedron: A New Way To Visualize First Responder Stress

The brain is a very complex organ, especially when placed under stress. It is essential for firefighters and all first responders to understand the role that their performance psychology plays in their thinking when sizing up a scene. For example, the frontal lobe, where reasoning and logic generally occur, can become impaired during stressful events. When the brain is under stress, the frontal lobe area shuts down or becomes impaired, and we move toward the “fight or flight” response, controlled by the amygdala. The amygdala, when prompted, tends to cause us to make more impulsive decisions.

Now, I don’t expect you to study this brain information thoroughly, but it is essential to understand that a natural process occurs during stress. Realizing the process will occur helps us to recognize the triggers in the environment, for example, on the fire scene. It helps us to realize we need to slow our thinking down, even if only for a few seconds, and take a breath before we key the radio or bust down a door.

As Mike Tyson used to say,”Everyone has a plan until they get punched in the mouth.”Well, every fire officer has a plan until… Well, I will let you fill in the blanks on that one.

Words Have Power

Let’s be honest: every firefighter dreams of pulling up first due to that big fire. They dream of giving that size-up and telling everyone out in radio land, “We got one, boys.” After all, what was all that training for if you can’t use it?

However, when giving the initial radio report, the officer or lead firefighter must consider a few things, namely the 3 Ts.

- Telling tales

- Tone

- Tactical aggression (controlled)

Telling Tales

Be exact about what you observe over the radio. Do not exaggerate for effect. Call it as it is. Is the house 50% involved? Then, call it out. Don’t say a structure is “fully involved” when you have light smoke and vice versa. This causes unnecessary and sometimes dangerous emotions to be stirred up in members on incoming trucks. Give a precise picture of what you see. Words have power, more than we sometimes realize.

Tone

Keep the tone of your voice clear and calm, which may mean stopping to take a breath before you speak. We are human; hormones and excitement can catch us off guard. Speak clearly so that you can be understood the first time you say something. This also instills confidence in your crew and the crews coming in that you have a handle on the situation.

The speed at which you speak and the volume that you use can calm a chaotic situation down. The next-arriving apparatus should be able to understand your situation but not feel a sense of chaos based on the tone of your voice. You want the next-arriving crews to have a clear mind to make clear decisions, thereby continuing the loop of sound, informed, tactical decision-making. As we have been taught for years, chaos breeds chaos, and calm breeds calm.

Tactical Aggression

Controlled tactical aggression is employed as soon as your apparatus arrives. The idea is to act aggressively and safely, moving with a purpose to instill confidence in those around you. Screaming and barking orders does not accomplish anything. Controlled, confident, and tactically sound tactics do.

Controlled aggression requires a multi-phase approach that every seat on the truck can employ. Using these simple steps, you can improve your control of yourself and any scene. It will be challenging, but it can give you a program or guideline to follow.

- Realize that, under stress, your brain reacts differently. However, you can train yourself to recognize the changes.

- Identify the problem you are responding to and what it means to you.

- Key the radio to announce your arrival, but then unkey and wait a few seconds to give your size-up. Let your brain catch up to the situation it is analyzing.

- Measure the language, tone, and speed of your voice you use, and the power of terms such as “fully involved,” “well involved,” and “smoke showing.” Those mean different things to everyone.

- Identify risk vs. gain without emotions coming into play.

- Observe the scene before leaving the truck.

- Complete a 360° size-up of the structure when possible or as much as you can.

- Slow down your crew if they are overstimulated. This can be done by simply speaking in a confident and calm tone.

- If the situation seems overwhelming, do not get caught in the “mental drain.” Slow your process for 10 seconds and reassess your actions and the situation. The fireground changes rapidly.

- After every call, reasonably ask yourself: “Did I do my best on the battlefield?” If the answer is “no,” then make a checklist of what you could have improved. However, be fair with yourself. Perfection will never be achieved, but humility and self-reflection are qualities of the best leaders and firefighters.

*

It’s essential to understand that “controlled tactical aggression” is a concept that requires humility and self-reflection. Although it may not fit into the aggressive culture of the fire service, slowing your mind down will improve your aggressive outcomes and you will improve over time.

Leadership is a broad term and is heavily discussed and analyzed. Controlled tactical aggression does not discriminate, and all ranks are welcome to employ it. If you know the “why,” the way becomes plain.

Mike Norris has been serving in the fire service for more than 25 years. He is the captain of an engine company in the St. Louis Metro area. He is a firefighting instructor and has published multiple training articles on commonsense firefighting tactics and leadership strategy.