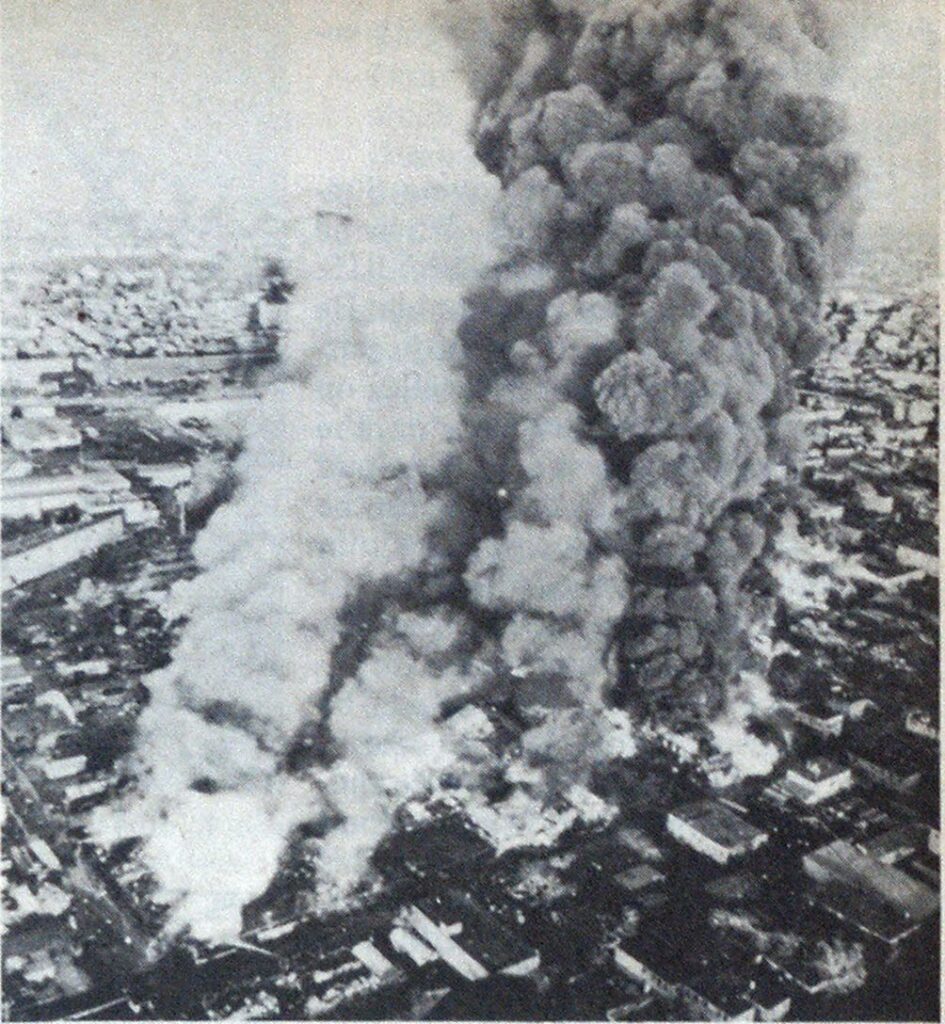

Conflagration Rages Through Chelsea, Mass.

City’s second massive fire In 65 years levels 16 blocks, Aid sent by 80 departments

For the second time in 65 years, a conflagration has swept through Chelsea, Mass. The two fires started less than 100 yards apart and both started on a Sunday in the 2-square-mile city of 30,000 population on the northern side of Boston Harbor.

The conflagration last October 14 destroyed 360 buildings in a 16-block area of about 30 acres. A preliminary estimate of the loss is about $100 million, the Massachusetts Property Insurance Underwriting Association reported. It was estimated that up to 90 percent of the fire damage was not insured and involved long-vacant property held by the Chelsea Redevelopment Authority.

No lives were lost, but about 1000 persons were left homeless. It was estimated that 600 persons were employed in the destroyed property.

Apparatus from 80 municipalities assisted the Chelsea Fire Department.

Conflagration in 1908

The first conflagration started on Palm Sunday, April 12, 1908, and 19 persons died as flames swept a third of the city. The $12 million fire destroyed 3500 buildings.

For many years, the major business in Chelsea has been junk yards, which salvaged waste paper, rags, tires, and plastic and metal scrap. The area burned has always been known as the Rag Shop District. It consisted of a mixture of small manufacturing plants, warehouses for storing and sorting all kinds of salvageable materials, and hundreds of two and three-story tenements that were hastily thrown up after the 1908 conflagration. Most of these buildings were in a bad state of repair and weatherbeaten. Blocks of them were scheduled for demolition under an urban renewal project and many tenants had already relocated.

Every fire chief who served after the 1908 conflagration was well aware that a similar fire could happen again, and a National Fire Protection Association report in 1925 described the Rag Shop District as “practically one unbroken fire area.”

Water system

The city government had been trying to obtain a federal grant for a $3 million project to recondition the water system after first the fire department and then an engineering firm pointed out serious deficiencies in the water system. The reconditioning project would have included cleaning and cement-lining the larger mains—the largest of which were 16-inch mains— replacing some of the smaller mains with larger pipe, and looping dead-end 6-inch mains. Flow tests had shown deficiencies of as much as 45 to 50 percent of the minimum flow required by underwriters. Fire department tests found that 93 hydrants, one-sixth of the total, delivered little or no water.

The Chelsea Fire Department is headed by Chief Herbert C. Fothergill, who has been in the department 26 years, the last seven as chief. Five engine and two ladder companies are housed in four stations, all built between 1887 and 1910 and with no significant modernization beyond the removal of the horse stalls.

The apparatus is in good condition and well maintained. Engine companies respond with three men and ladder companies with two, including the officers.

First alarm

Sunday, October 14, was a beautiful fall day in Chelsea. The sky was clear in the afternoon and the temperature was near 70, but there was a steady 40-mile west wind. There had been little rain and the air was dry.

At 3:56 p.m., Box 215 on Summer Street, in the Rag Shop District came in at fire alarm headquarters. The regular first-alarm assignment responded as Ladder l,and Engines 1, 2 and 5. Deputy Chief William Coyne, returning from a small grass fire, received the alarm on his car radio.

Engine 5, located about 600 yards away, was the first company on the scene. The men attempted to lay a line into the front of the fire building on Second Street, but the wind-driven heat, smoke and embers forced them back. With the arrival of the rest of the first-alarm assignment, an attempt was made to lay a line to the side of this building. These efforts were thwarted by piles of assorted junk, ever-increasing clouds of thick black smoke and the rain of burning embers.

Coyne ordered a third alarm, skipping the second. This brought in Engines 3 and 4 and Ladder 2, which was all of Chelsea’s active apparatus. Under the automatic mutual aid system, the third alarm brought in three Boston engine companies and an Everett engine company.

Fourth alarm struck

Chief Fothergill was enjoying Sunday at home, across town. When he heard the third alarm from Box 215, he knew he was in for real trouble. He jumped into his own recently purchased new car—it had 4500 miles on the odometer—and headed for the scene. Motorists attracted by the cloud of smoke were already clogging up the streets. He was able to get to within 500 yards of the scene, where he left his car. The next time he saw his car, it was a burned-out mass of junk.

Upon reaching the fireground, he immediately ordered a fourth alarm, which was the limit of automatic mutual aid response. Everything beyond that had to be special-called. This fourth alarm brought in another Boston engine company along with one engine company each from Revere, Malden and Saugus and a ladder company from Revere.

Fire alarm headquarters called in all the off-duty operators and all off-duty fire fighters. Civil defense units throughout the area were activated. All off-duty police were mobilized and outside police were called in to help handle traffic and prevent looting. As half of the city is surrounded by water, sealing it off was not too difficult.

The recently adopted policy of the State Police to allow troopers to take their cruisers home when off duty made about 75 of these men available for traffic control. An official of the Port Authority was finally located who authorized removal of the barriers on Tobin Bridge, which had been closed after a crash damaged structural members, so that the lower deck could be used by emergency vehicles.

Conflagration reported

At 4:28 p.m. Fothergill called Newton Fire Control, stating that he had a full-scale conflagration completely out of control. Before the end of operations, Newton Fire Control had dispatched into Chelsea 82 engine companies—some of them two-piece companies—12 ladder companies, six lighting units and a number of other special units. In addition to this more than 100 units that were dispatched to Chelsea, as many more were moved around in the distant suburbs co cover vacated stations.

Meanwhile, the fire was traveling unabated. The updraft from the center was accelerating the steady 40-inch wind on the fireground. A direct frontal attack with heavy streams was impossible, due in large part to the meager water supply. The north side of the fire area did have a good firebreak provided by the maze of railroad tracks and sidings operated by three railroads. One of the few favorable conditions was that it was Sunday and the usually busy trackage for commuter trains and local freight switching was quiet.

Companies that attempted to work lines into the flanks found themselves trapped and had to back out, sometimes unable to save their hose lines or nozzles. More than 3000 feet of hose was lost. Medford Engine 5 was trapped and destroyed. Many other pieces suffered slight damage and blistered paint.

Water pipes break

As buildings collapsed, sprinkler lines and service pipes broke off, allowing precious water to go to waste. To bolster the failing water supply, valves were opened between the Chelsea high and low service systems. The fire area was on the low service system and nearly at sea level. Normal static head on the low service was about 60 psi.

This move created another problem: It reduced the pressure on the high service system to nearly zero at Memorial Hospital and the Soldiers Home, which are on a high hill. A couple of engine companies were dispatched to these institutions in case it became necessary to pump water from the bottom of the hill to feed sprinkler connections. Another move to bolster the water supply was the opening of a couple of valves on emergency cross connections with the Everett system.

By 5 p.m., the retreat of fire fighting forces was slowing down. A stand was being made in the middle of the blocks between Spruce and Arlington Streets. A frontal attack was being made northward along Everett Avenue, a broad thoroughfare. This line of defense was held from Arlington Street to Fourth Street. Station 5, in the triangle bounded by Everett Avenue, Arlington Street and Fourth Street, was saved, but not without considerable damage to the station.

The fire, still driven by the high wind, jumped Everett Avenue, consuming everything between the railroad and Fourth Street, including the Public Works Department yard and buildings with all equipment. It was on Arlington Street that the last ditch stand was made which saved the Williams School, reputed to be the largest elementary school building in New England.

Wide World Photos.

Fire halted at school

To defend the Williams School, lines were brought from the rear onto the roof. These lines were fed by engines on hydrants close to the larger mains on Broadway and Everett Avenue, which under normal conditions have a capacity of nearly 5000 gpm. Two engine companies were holding the fire out of buildings on Fourth Street near Arlington Street. Both sides of Vale Street were destroyed and everything on the north side of Arlington Street opposite the Williams School was fully involved.

It was here, on a hydrant directly in front of the Williams School, that the crew of Wakefield Engine 2 hooked up their pump. Feeding their own mounted deck gun, they met the full force of the fire directly in the face of driving wind. With small fog lines wetting them down as clouds of steam rose from their protective clothing, they stuck to their gun. A Lynn ladder company set up at Fifth and Arlington Streets with two ladder pipes at different levels and was able to maintain effective streams on the burning building opposite the school. If this school had gone, it not only would have been a crippling blow to the school system, but would have been a serious fire threat to the entire Chelsea business district.

During the course of the fire, most of the incoming out-of-town apparatus was lined up in a small church parking lot about 200 yards from fire alarm headquarters. From this marshaling yard, apparatus was dispatched to fill the Chelsea stations. Normal fire alarm dispatching was maintained, using the same running cards for these out-oftown companies as if they were regular Chelsea companies.

A few out-of-town companies were stationed at strategic locations near the path of the falling brands. Civil defense volunteers acted as pilots for these companies, along with a number of retired fire fighters who volunteered their services. The civil defense rendered considerable assistance with portable radios as the out-of-town companies were on different frequencies.

Embers cause spot fires

There were continuous alarms coming in for spot fires caused by flying embers landing on porches and ledges as much as half a mile from the fire. As soon as one assignment left a station, their place was taken by apparatus moved in from the marshaling yard so that dispatchers knew that a full complement was always ready to answer the next alarm.

The most serious of these spot fires was one which involved the upper part of City Hall.

Many out-of-town chiefs were amazed at the manner in which fire fighters from widely scattered communities were able to work smoothly together. They all seemed to agree that it was the result of the standard system of training given by the Massachusetts Fire Fighting Academy.

By 10 a.m., the perimeter of the fire area was secured and some of the outof-town companies were released, although some of the buildings within the area continued to burn fiercely, particularly those loaded with baled paper or rags. Wetting down and overhauling operations went on for days.

The all-out on Box 215 was not struck until 7:58 a.m. October 17, 76 hours after the first alarm.

The cause of the fire is still undetermined, but there is a suspicion of arson.