JOSEPH W. PFEIFER

Superstorm Sandy illustrates the full spectrum of Fire Department of New York (FDNY) preparedness and response capabilities along with its commitment to community recovery. This was realized when a rare meteorological event occurred merging Hurricane Sandy with a nor’easter to create a “perfect superstorm.” With its record low pressure, the storm stretched almost 1,000 miles in diameter and quickly became the largest and most damaging Atlantic Basin storm to hit the East Coast. As the superstorm slammed into New York City (NYC) on October 29, 2012, at the peak of high tide during a full moon, it brought a storm surge of 13.8 feet and 65-mile-per-hour (mph) sustained winds and gusts up to 92 mph. If this extreme storm was not enough for first responders to contend with, the storm sparked a seldom-experienced conflagration in Breezy Point, Queens, as well as other multiple-alarm fires and lifesaving emergencies around the city that would tax FDNY and all emergency management.

The early history of NYC is marked by several historical conflagrations. The First Great NYC Fire of 1776 occurred while the British occupied the city; nearly 25 percent of the city was burned. In 1835, the Second Great NYC Fire ripped through lower Manhattan, destroying the New York Stock Exchange and well over 600 buildings. A decade later, in 1845, fire again devastated lower Manhattan by destroying 345 buildings. These conflagrations resulted from high winds that spread fires in the direction the wind was blowing. The hot gases on the wind’s leeward (downwind) side ignited combustible material, rapidly extending the fire.

|

| (1) Dozens of houses were already on fire in Breezy Point before FDNY arrived on the scene. (Photos 1-2 by Todd Maisel, NY Daily News via Getty Images. |

Since the establishment of the FDNY in 1865, some of the most notable fires have occurred recently in the 21st century. In lower Manhattan, the 9/11 World Trade Center (WTC) fires caused the largest loss of life with 2,750 killed by the collapse of two 110-story high-rise office buildings. The 2006 Greenpoint Terminal Market fire in Brooklyn engulfed 10 large industrial buildings. This was not a conflagration but a rare firestorm that sustains its own wind system by drawing air toward the burning buildings. The difference between a firestorm and a conflagration is that prevailing weather of low-speed wind permits firestorms to develop, whereas high-speed wind causes conflagrations. Hurricane Sandy’s high winds coupled with the storm surge that created an electrical short in one home. The short then triggered the conflagration in Breezy Point, which destroyed 126 homes and damaged 22 others, making it the largest private-residential fire in the department’s history. The fires combined with the storm surge accounted for the complete destruction of more than 10 percent of the 2,837 homes in Breezy Point. Overall, every structure in this small beach community received significant damage from fire, water, or wind.

PREPARING FOR THE UNTHINKABLE

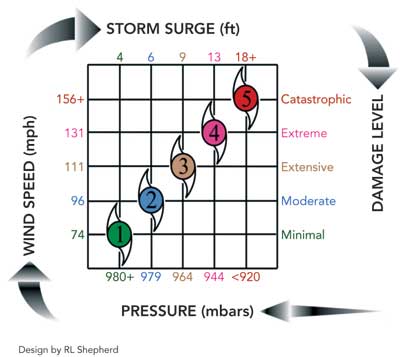

Over this past summer, FDNY’s Center for Terrorism and Disaster Preparedness (CTDP) designed and conducted a series of tabletop exercises on hurricanes. They were held in the Rockaways, Staten Island, Coney Island, and City Island. Representatives from local communities and government agencies as well as utility companies attended to exchange ideas on hurricane plans. Discussions dealt with storm surge, evacuation, power outages, response, and potential problem scenarios. The handout (Figure 1) given to participants explained how a storm surge of 13 to 17 feet is equivalent to the damage level of a Category 4 hurricane.

| Figure 1. Preparing for the Unthinkable |

|

| Saffir-Simpson Hurricane Scale indicates damage levels from wind speed and storm surge. |

In addition, on April 12, 2012, CTDP designed a simulation of a Category 3 hurricane for 50 West Point cadets at FDNY’s Emergency Operation Center. The simulation had the cadets coordinate civil and military assets to manage the disaster. Major General Peter Aylward from the National Guard Bureau and a member from the New York National Guard participated, as did a Northern Command representative who joined the exercise remotely. Through scenario-based exercises, highly adaptive organizations prepared their members to improvise when confronted with novelty and low-probability/high-impact events.

|

| (2) The high winds blew back tower ladder streams, which limited extinguishing capabilities. Members in tower ladder buckets also had to contend with the high winds, intense heat, flying brands, and heavy smoke. |

Little did any of us know how prophetic these exercises would become as the storm surge and winds from Hurricane Sandy caused havoc in coastal communities.

ROCKAWAY IS BURNING

Hearing reports of flooding and multiple fires along the narrow Rockaway Peninsula, Chief of Operations James Esposito at 2245 hours told me to meet the Queens borough commander, Deputy Assistant Chief Robert Maynes, at the edge of Howard Beach to discuss the best strategy to manage multiple fires in the Rockaways. In the middle of Cross Bay Boulevard, we decided the best line of attack would be that Maynes command the Belle Harbor fires and I command the Breezy Point fires.

At 2304 hours, Queens Box 8300 was transmitted for multiple houses on fire at Breezy Point. Crossing the Marine Parkway Bridge from Brooklyn into Queens, units saw Breezy Point in complete darkness except for the fiery orange glow reflecting off clouds. The road leading to Breezy Point appeared to be a river; it was completely covered with three feet of water. Unable to proceed any farther in my SUV, I flagged down a responding engine (E). The irony was too surreal as E-10, from two boroughs away, stopped to pick up the first chief officer to this unprecedented fire. Eleven years ago, we were the first to arrive at the WTC attacks, and now we were among the first units to respond to another major disaster. The engine smoked, and the exhaust gurgled like a boat while the chauffeur plowed through two miles of streets with water as high as the rig’s headlights. While responding, E-329 and E-14 reported poor water pressure on Beach 207th Street, which was the eastern edge of the fire. From the crew seats in the back of E-10, I had the engine company chauffeur take a hydrant at the end of Beach 208th Street, which was on a new water main and closest to the northern exposures. Positioning units would later prove pivotal in saving numerous homes.

At midnight, dozens of houses were already on fire, fanned by hurricane-strength winds from the southeast, which forced firefighters to battle this growing conflagration on multiple fronts. This rapidly moving fire, energized by hurricane force winds, showered the area with burning embers the size of golf balls and drove flames to the west and north, consuming building after building, from block to block. To complicate matters further, there was almost no water pressure in the hydrant because of the extensive storm damage. The conflagration became its own “perfect storm,” combining an advanced fire with ample combustible material, hurricane-force winds, little water pressure, difficult access, and few firefighting resources. Faced with this complex and novel event, I, as the only chief on the scene, took command and transmitted a third alarm. Subsequently, the Breezy Point Conflagration would reach six alarms, pulling scarce fire resources from all over the city.

The firefighting strategy was to aggressively halt the violent fire spread without jeopardizing the lives of firefighters. A tactical “Plan A” was implemented to flank the fire by stretching several handlines from Beach 207th and Beach 208th Streets to protect the eastern and northern flanks, as well as setting up Tower Ladder (TL) 159 in the northeast corner to stop the fire from pushing north. TL-12 and TL-142 were deployed on the northwest perimeter to impede the northwest direction of flames; TL-115 later reinforced this position. However, without a reliable source of water, battling intense wind-driven flames and smoke became a daunting task.

ADAPTING TO NOVELTY

One of the major characteristics of complex disasters is the presence of novelty or events that have not been seen before.Every so often, senses are overwhelmed by too many new and dynamic events. First responders search for patterns that match standard operating procedures but are unable to connect what they see to their experience. Decision making slows down as firefighters hunt for what to do as they strain to absorb the scale of this mass fire. It is at this point that commanders must narrow the focus of units to achieve specific missions. Such tactical framing is accomplished by sectoring the fire and ordering engine companies and the satellite units to concentrate on finding a usable water source. Ladder companies were instructed to assist in getting supply lines in position. This was followed by specific directions to cut off the advancing fires.

Within this framework, firefighters were able to customize procedures to attain a reliable water supply. Firefighters used the same storm surge water, which caused so much damage, to extinguish the fire. With engines sitting in three feet of water, firefighters drafted water directly from flooded streets and stretched heavy hose through these storm-made lakes to relay pumpers and tower ladders. Firefighters in the tower ladder buckets wore full bunker gear and self-contained breathing apparatus as heat and smoke pounded their position, making this a difficult and dangerous job. Also, chin straps were tightened to prevent helmets from blowing away. As the firefighters continued to battle this gigantic inferno with floodwaters, they developed new ways to manage their innovative street drafting.

Some firefighting units used plastic milk boxes as strainers, but when they clogged, units had to manually move the hose to adjust its height to maintain suctions; too low to the ground or too high to the surface would cause the suction to clog with debris. Others continued to innovate by creating drafting relays. In the Eastern Sector, engines were drafting water independently on Beach 207th Street. To ensure adequate water volume and pressure, engines drafted and relayed water (inline pumping) from E-96 to E-247 and finally to E-14, which supplied E-329. With a good water supply, and under the supervision of Battalion (B) 53 and off-duty battalion chiefs, lines were stretched by engines and ladders to make a defensive stand and prevent fire from traveling farther east and north.

Improvisational drafting also took place in the Northern Sector by E-10, E-240, and E-23. While this occurred, E-225 and E-284/Satellite (Sat.) 3 serendipitously secured a working city hydrant on the main road of Rockaway Point Boulevard, but this required stretching 2,500 feet of six-inch hose. Sector management by B-46 and Rescue Battalion 2, city hydrant connections, innovation drafting techniques, inline pumping relays, and pure determination combined to supply water for three TLs and numerous handlines, which saved many homes.

Yet, a large section of the fire, moving fiercely to the west, could not be attacked with heavy-caliber streams because there were no roads in this 26-block section of Breezy Point—known as the “wedge” because of its shape. Access was by narrow six-foot sidewalks or debris-ridden sand lanes with dangerous sink holes located behind homes. This meant that firefighters had no option but to stretch 2½-inch handlines. However, the radiant heat and wind-driven convection currents were too hot and kept firefighters at bay, preventing them from making an initial direct frontal attack. The fire behaved as if it were a mythological dragon; it roared with each gust of wind and blew intense heat on buildings before the structures exploded into 50-foot-high flames. Anything in the path of this metaphoric incendiary creature would be reduced to ashes.

In the middle of all this danger, a woman in a wheelchair with a male companion was spotted between houses that were in the direct path of the raging fire. Immediately, firefighters from L-142 and Squad 288 were sent to rescue them. This brought a new reality to bear that others may be trapped or entombed in the growing field of smoldering ruins and advancing fires.

As each building erupted in flames, the natural gas lines melted and fed the fire. The utility company was requested to turn off the natural gas mains supplying Breezy Point, but this was difficult with much of the area underwater. L-157 was then tasked with shutting down numerous gas meters.

Assigning unit-specific missions, sectoring the fire, and assigning a command channel allowed me to step back and think about how best to manage this incident. Commanding at extreme events requires leaders to visualize the incident as if they were standing on a hill or perched on a balcony overlooking the firegrounds. Having spent summers in Breezy Point, I was able to create a mental map of the blocks on fire; and using the electronic command board (a 10-inch tablet) from Field Comm, I was able to picture the deployment of units. Firefighter James Long, who also spent years in this community, provided descriptive reports on the extent of fire damage. From these pictures, I developed “Plan B” (Figure 2), which was to get well ahead of the flames to cut off the fire’s advance. This meant the possibility of sacrificing a number of homes as a last resort. Additional alarms were transmitted with specific instruction to approach from the west and position apparatus near the corner of Oceanside and Lincoln Walk, three blocks ahead of the western fire front.

| Figure 2. Visualizing Plan B |

|

| The incident commander visualized a mental map of the conflagration (the shaded area) and then ordered a three-prong attack that combined flanking strategies with direct tactics to contain the fire in this section of Breezy Point known as the “wedge.” |

Because of the scale of fire and the unpredictable nature of hurricane winds, I knew that I had to reinforce my two-plan strategy. Again, I visualized the fireground and saw one other option, which would become Plan C: I gave orders through the Queens dispatcher to have a sixth alarm assignment approach from the west along the ocean facing the promenade. This had its own dangers because it was closest to the beachfront, an area that sustained extensive damage and flooding. We did not know if the concrete boardwalk was passable and if there were any workable hydrants. Drafting from shallow water in soft sand is almost impossible; it would quickly clog the pumps. This approach from the south had the advantage of being upwind, but it was difficult to access, and units would be playing catch-up to a fast moving fire.

Firefighters, including a few off-duty and volunteer members, battled this unique conflagration for hours. Across the fireground, there was a commitment to stop this monstrous fire without getting any firefighter seriously injured in the process. Taking a wrong position would jeopardize firefighter safety because one could not run fast enough to get away from a wind-driven fire that would ignite entire buildings. Chiefs, company officers, and firefighters knew the limits of safety and the dangers of this operation.

Then suddenly, in the early morning hours, after we battled this fire for six hours, the wind shifted from the southeast to only out of the south. This gave us the opportunity to stop the western advance of the fire with three handlines. Plan B was implemented; E-231 drafted water and hastily deployed handlines with E-227, E-323, and E-310 under the supervision of B-58, B-33, and the Safety Battalion, to contain the western flank. One volunteer unit with a four-wheel-drive pumper was able to access the promenade along the ocean to assist in Plan C.

|

| (3) A view of the Breezy Point, Rockaway, Queens conflagration from a Task Force Guardian copter during a US&R aerial recon. (Photo courtesy of the Federal Emergency Management Agency.) |

When exercising leadership at large-scale disasters, ICs must not only give verbal commands but must also create a deliberate calm to visualize the fireground. Strategic opportunities are generated by anticipating fire movement and tactically positioning units for the dynamic changes in fire behavior. This was accomplished by getting firefighters to adapt to novelty so they could take advantage of natural breaks and changing fire conditions. Plan A used small physical separations and flanked the fire to contain it on the northern and eastern exposures while Plan B deployed units to contain the fire on the western flank. The southern flank was held in check by the winds out of the south and Plan C.

At 0700 hours on October 30, the fire was contained, and I passed command to Deputy Assistant Chief Jack Mooney, who directed final extinguishment. As the sun began to rise, it became evident that a six-block stretch of homes on both sides of the street from Ocean Avenue to Jamaica Walk were destroyed by fire and others were seriously damaged by impinging flames. It looked as if bombs were dropped to level a section of Breezy Point.

In the rubble, search and rescue teams looked for signs of victims. The Breezy Point Cooperative was asked to canvass its community for missing persons. The New York City Police Department was also asked to check its databases.

|

| (4) This photo of the devastation was taken on November 1, 2012. (Photo by Steve Spak.) |

After multiple searches and no one being reported missing, the fire incident was finally closed some 40 hours after the units first arrived. Breezy Point suffered destructive fires and floods, but there were no fatalities or serious injuries, which was nothing less than miraculous.

RECOVERY MISSION

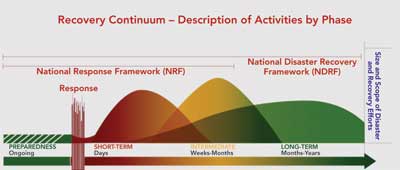

| Figure 3. Recovery Continuum |

|

| Recovery Continuum from the National Disaster Recovery Framework. |

As firefighters began to walk the smoldering debris field, residents came up to thank them for saving their community from further devastation. News channels and front-page news articles praised the response to this epic disaster, but there is another equally important part of this story. As the FDNY moved seamlessly from response to recovery, firefighters had to cope with not only flooded homes but also large lakes and streams created by the violent storm surge. Battalion Commander James Dalton had a theory that pumping out areas of standing water would lower the water table and then the community would be able to manage the problem of flooded homes. Through the efforts of Special Operations, FDNY conducted massive dewatering operations of large common areas with 3,000-gpm portable pumps. Hundreds of thousands of gallons of damaging flood waters were pumped back to the ocean and bay. Task forces were formed to help homeowners dewater and remove debris from their houses. Additional task forces were created to cut up fallen trees and decks that were blocking roads and walkways. FDNY member-staffed Incident Management Teams worked with OEM, the National Guard, volunteer groups, and many other agencies. The mission was to use the department’s core response capabilities for short-term community recovery.

For the first two weeks after this destructive superstorm, interagency meetings were held with local community leaders to coordinate recovery efforts. Initially, I chaired the meetings and provided the Breezy Point Cooperative with a framework for conducting meetings and preparing a “Community Action Plan,” which described accomplishments in the past 24 hours, objectives for the next 24 hours, and a safety plan. Immediately after an extreme event, the government takes the lead to facilitate the beginning of short-term recovery; however, it is important to quickly turn recovery over to the community and have government then support the local leaders. FDNY’s mission after response was to foster community resilience through its task forces and recovery assistance support. This concept is in accordance with the primary mission areas of Homeland Security for prevention, protection, mitigation, response, and recovery.

The community of Breezy Point, as well as the entire city, depends on the FDNY for preparedness, response, and recovery. The department has adapted its core competencies to restore neighborhoods to normal. Now more than ever, people view the local firehouse and EMS station as part of their local community and see the FDNY as an agency they can depend on before, during, and after a disaster.

Had the firefighters not taken advantage of the wind shift, the fire would have burned from the ocean to the bay, consuming more than a thousand homes. As the IC, it was an honor for me to fight this dangerous conflagration with firefighters and medical personnel who were prepared as they operated bravely and safely during the fiery moments of Superstorm Sandy. Their dedication and service to those in need bring about community resilience. New Yorkers witnessed how the FDNY not only responds in times of danger but also stays with them during recovery.

References

Eden, L. The Whole World on Fire: Organizations, Knowledge, & Nuclear Weapons Devastation. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2004.

Leonard, H. & Howitt, A. “Leading in a Crisis: Observation on the Political and Decision-making Dimension of Response.” in Helsloot, I. et al. (Eds.) Mega-Crisis: Understanding the Prospects, Nature, Characteristics and the Effects of Cataclysmic Events. Springfield, Ill: Charles C Thomas Publisher, 2012.

Pfeifer, J. “Firestorm at the Greenpoint Terminal Market.” New York: WNYF 06/4, 2006, 12-15.

● JOSEPH W. PFEIFER is an assistant chief and a 31-year veteran of the Fire Department of New York and the chief of counterterrorism and emergency preparedness. He has master’s degrees from the Harvard Kennedy School, Naval Postgraduate School, and Immaculate Conception. He is a Senior Fellow at the Combating Terrorism Center at West Point and at the Ash Center for Democratic Governance and Innovation at Harvard University. He writes frequently and is published in several books and journals.

Fire Engineering Archives