By Connie Pignataro

According to the American Burn Association (ABA), approximately 486,000 people receive medical treatment for burn injuries annually. Most of the injuries are minor and do not require hospitalization.1 But, for those 45,000 people who do require more extensive care for burn injuries, fire/emergency medical services (EMS) personnel will likely be first on scene to treat these patients. Education is critical so that the first hours of treatment following the burn injury will allow for optimum results.2

“The initial care for the burn patient does have a significant impact on the long-term outcome of these patients,” says Deborah Krauser, director of trauma and burns, Kendall Regional Medical Center in Florida. “We feel that the paramedics’ management is extremely important.”

To give paramedics, along with physicians, physician assistants, and nurses, the education to assess, stabilize, and treat burn patients during the first critical hours post injury, the ABA has developed the Advanced Burn Life Support (ABLS) course. This seven-hour course is available nationwide.

“The ABLS class really directs concise best practices using evidence-based recommendations,” explains Krauser, also an ABLS instructor. Although local protocols may differ, this article will address initial treatment recommended by the ABA and taught in the ABLS course.

Causes of Burns

Burns are caused by friction, heat, cold, radiation, chemical, and electrical sources. Heat causes the most burn injuries, with flame being the most common mechanism (41%).3

Depending on the type of heat, the skin may respond differently. For example, the skin will more likely show immediate deep burns with flame or hot grease as opposed to scald injuries, which may initially appear more superficial. Alkaline and acid chemical burns will also vary. With alkaline burns, the tissue will turn into a viscous mass; with an acid burn, the architecture of the dead tissue will be preserved but damaged.3

The injury from an electrical burn may appear to be minor on the surface of the skin when, in fact, deep tissue damage is being concealed. Approximately 1,000 people die annually from electrical injuries. Fractures, dislocations, and cardiac dysrhythmias are associated with this type of burn.2

Burn injuries can be particularly challenging to fire/EMS personnel, as the injuries can be complex and multifaceted. This type of injury can involve respiratory, cardiac, exposure, and other traumatic injuries depending on the extent of the burn and the cause. For example, blast injuries may not only involve burns but may also include radioactive or chemical exposure, direct organ damage from the shockwave, blunt and penetrating injuries, and crush injuries.2

Scene Safety

As with any traumatic injury, the first course of action is scene safety. Remove the patient from the hazardous environment. For instance, with burns caused by heat, move the patient away from any further exposure to the heat. For electrical injuries, first responders must confirm that the scene is safe from electrical current. If chemicals or radiation is involved, a specially trained hazardous materials team may be required to extricate the patient from the scene and decontaminate the patient before treatment.

After scene safety, treating any life-/limb-threatening injuries will be the next course of action. Burn injuries may be overwhelming for fire/EMS personnel. Following the ABCs (Airway, Breathing, Circulation) of treatment and cooling any burns will keep first responders focused.

Body’s Response to Burns

Immediately following a burn, the body triggers an inflammatory response to promote healing. In severe burns, this inflammatory response can become uncontrolled. Along with the severity of the burn, a number of other factors can influence the degree of inflammation including the cause of the burn, inhalation injury, any preexisting medical conditions, age, exposure to toxins, and other trauma.3

The inflammatory process that is meant for healing becomes destructive and may even lead to delayed healing, organ failure, infections, or death. Depending on the severity of the injury, this inflammation may last for weeks, maybe even months, and will need continuous monitoring throughout long-term care.3

(1-5) On December 6, 2016, the patient in the photos (Kevin) and two other workers were tasked with resealing a pump. Because of a chemical reaction, the pump exploded, causing 500 gallons of molten liquefied plastic to pour from the pump. One of the workers was killed and the other two were seriously injured. Kevin sustained injuries to 65% of his body. He spent 72 days in a medically induced coma and underwent numerous procedures during that time. He was expected to be in the hospital for a year but was able to leave after 144 days, which he attributes to a change in attitude and embracing the process. To read more about Kevin’s journey, go to https://burncenters.com/patient-stories/burn-survivor-soars-to-new-heights. (Photos courtesy of Burn & Reconstructive Centers of America.)

Airway

Stabilizing the airway is critical. Inhalation injury is a leading cause of death for adult burn victims.4 An inhalation injury can be from aspiration or inhalation of superheated gases, steam, hot liquids, smoke, or a combination thereof. Injury to the airway does not always accompany burn injuries, but when it does, the patient must be closely monitored. It has been found that 2-14% of burn patients admitted to a burn center have inhalation injuries. Significant burn injury along with inhalation injury increases the risk of death for the patient.2

Burns require fluid resuscitation, but this additional fluid may increase upper airway edema in those patients who have also sustained inhalation injuries. Early intubation may be necessary if the following indications are noted2:

- Signs of airway obstruction (stridor, respiratory muscle use).

- Extent of burn area (> 40-50%).

- Extensive/deep facial burns.

- Burns inside the mouth.

- Possible respiratory compromise (respiratory fatigue, poor oxygenation).

- Decreased level of consciousness.

Cervical spine immobilization, or full spinal immobilization if warranted, will need to be performed simultaneous to airway stabilization.2

Breathing

Patients with inhalation injuries should be given 100% oxygen via nonrebreather until their Carboxyhemoglobin (COHb) is within normal levels (<5%). The half-life of COHb is cut from 4 hours to 45 minutes with the administration of 100% oxygen as opposed to just room air.3 COHb should be monitored continuously in any patient with an inhalation injury. Oxygen levels should also be monitored by a pulse oximeter using an unburned extremity or ear.2

Fire/EMS personnel must assess bilateral breath sounds and rate and depth of breathing. Monitoring any circumferential full-thickness burns at the chest and neck area is of high importance to ensure that this type of injury does not impede breathing.2

Circulation/Cardiac

Although it is considered common for the heart rate in adults to be elevated to 100-120 beats per minute after a burn injury, heart rates greater than this may be a sign of hypovolemia, hypoxia, or even anxiety. Monitoring of the cardiac rhythm is crucial in patients whose burns were caused by electricity. Other causes of abnormal cardiac rhythms may be from a cardiac abnormality unrelated to the injury or an electrolyte imbalance.2

Blood pressure readings should be close to normal during the first few hours following a burn injury. If hypotension is noted, it could be a sign of a possible hemorrhage. This is especially true in cases also involving traumatic injuries. Depending on the location of the burn injuries, peripheral vasoconstriction may also give misleading blood pressure measurements.2

Shock Management and Fluid Resuscitation

The first 24 hours post burn injury are critical and can affect the patient’s recovery and long-term outcome. The body responds by reducing blood flow along with vasoconstriction. Managing fluids is vital to controlling the effects of shock in the body. Even with proper fluid management, shock can still be a threat.3

“Initial fluid management and proper fluid resuscitation definitely impact and can prevent complications due to over or under resuscitation,” says Krauser. “Swelling in places that are not supposed to have swelling can cause a lot of things, not just in the airway. It can cause compartment syndrome. There’s a lot of sequelae when patients get too much fluid on the front end.”

Fire/EMS personnel must understand the importance of managing fluid resuscitation, especially with patients with burns greater than 20% total body surface area (TBSA). The goal of fluid resuscitation is to restore cardiac output and blood flow to the tissues to prevent organ failure.2

Establish a large bore IV in peripheral veins for vascular access including underlying burned skin if necessary. For TBSA greater than 20%, a second large bore IV must be established. If those routes are unavailable, intraosseous (IO) routes may be considered. The most effective fluid to use for burn resuscitation is Lactated Ringers (LR) because it most closely resembles the body’s physiological fluids. The ABA recommends avoiding normal saline (NS) for burn resuscitation.2

The heavily debated issue on whether to use LR or NS for burn patient management is ongoing. According to Kimberly Linticum, a nurse practitioner with Burn & Reconstructive Centers of America, LR is preferred because it is most similar in composition to blood plasma.

“In burn patients greater than 20% TBSA, a shock state occurs, which results in fluid or plasma loss,” states Linticum. “This fluid loss is a result of a series of complex events that can result in massive fluid shifts, which displaces the body’s normal balance of fluid and electrolytes and results in a hypovolemic or low-volume state.”

She goes on to explain that burn patients usually require massive amounts of fluids in the first 24 to 48 hours following the injury. Since LR is slightly hypotonic, it is preferred over normal saline over concerns that normal saline in large volumes may cause hyperchloremic (too much chloride) metabolic acidosis and in turn potential kidney injury.

Fluids administered as close to the time of the burn injury as possible will help to prevent decompensated burn shock and organ failure.2 The initial fluids to be administered by fire/EMS personnel are based on the patient’s age per the ABA recommendations and are as follows2:

- 5 years old and younger = 125 ml/hour.

- 6-13 years old = 250 ml/hour.

- 14 years old and older = 500 ml/hour.

Once the patient is delivered to the hospital, a secondary survey is performed, and an adjusted fluid rate will be calculated using the patient’s weight and percent of TBSA of the second- and third-degree burns.2

Burn Wound Care

Stopping the burning process is of utmost importance. Only cool water should be used, never cold water or ice, as hypothermia can be induced, which reduces blood flow to the damaged area and will likely worsen the burn injury. In prolonged cases, a core temperature of less than 95°F may interfere with respirations and cause cardiac arrhythmias and even death, especially in pediatrics.2

“The skin helps the body maintain its temperature,” explains Krauser. “Patients with larger burn surface area are not able to autoregulate their temperature. While we want to make sure that they’re not still burning, we also want to make sure that they don’t get hypothermic.”

Remove any jewelry, body piercings, clothing, shoes, or diapers near or at the burn injury. If any material is adhered to the skin, cool the material and cut around it as close to the injury as possible. For facial burns, remove contact lenses, especially if the patient has sustained a chemical burn. Even if facial burns are nonexistent, the ABA recommends removing contact lenses before any edema develops.2

On arrival to the burn patient, fire/EMS personnel may not always be able to determine the depth of the injury, which, in some cases, may not be able to be determined for up to 48 to 72 hours. It is still up to paramedics to classify the severity of the burn injury, to the best of their abilities, by using the following categories3:

- First degree (superficial): Uppermost layer of the skin (epidermis); skin is red with intense pain.

- Second degree (superficial or deep partial thickness): Skin blisters with pain; increased risk of infection.

- Third degree (full thickness): Not typically painful; greater risk of infection.

- Fourth degree (full thickness, involving deeper tissue like muscle or bone): Blackened; no pain; typically leads to loss of the burned part.

First- and second-degree burns generally do not require surgery and will heal on their own without scarring. Third- and fourth-degree burns will require constant management or surgery.3

If bleeding is found at or near acute burn injuries, the paramedic must remember that these types of injuries do not bleed. There is an associated traumatic injury that must be found and treated.2

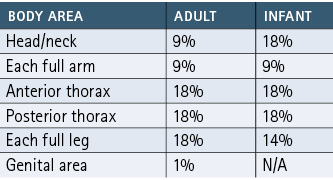

The “Rule of Nines” is a commonly used guide that will help the first responder determine the TBSA (Figure 1). The body regions represent 9% or a multiple thereof. Adults and infants share most of the same measurements except as listed below2:

Figure 1. Determining the TBSA

Only second- and third-degree burns are included in determining the TBSA.2 For example, if an adult has second-degree burns to the full length of the inside of both arms, the TBSA will be 9%. For scattered burns, the size of the patient’s hand (including fingers) can be used to determine the TBSA. An area the size of the patient’s hand measures a 1% area. Add up all the 1% areas to determine the TBSA.2

Pain Management

Burn injuries, especially in the more critical cases, will cause severe pain and anxiety. To control pain associated with burns, morphine (or opioid equivalent) is recommended. Benzodiazepines may be used to control anxiety. Both medications should be administered IV only, never intramuscular. Administer small, frequent doses and titrate to effect. Whenever administering these medications, continuously monitor the respiratory status.2

Transport

The ABA recommends elevating the patient’s head and affected extremities to 45° (unless contraindicated by spinal immobilization) once you have stabilized the patient; continue this throughout transport.2

Most jurisdictions will transport the burn patient to the nearest trauma center for initial treatment and evaluation. Patients with extensive burn injuries will have their long-term care provided by a specialty care burn center. Before being transferred to a burn center, the patient must be stabilized.

The United States has 120 burn care centers located in 40 states across the country.5 The following criteria would require the patient to be transferred to a burn center2:

- Partial thickness burns of greater than 10% TBSA.

- Burns that involve the face, hands, feet, genitalia, or major joints.

- Third-degree burns.

- Electrical burns, including lightning.

- Chemical burns.

- Inhalation injury.

- Patients with preexisting medical disorders that could complicate management, prolong recovery, or affect mortality.

- Any patient with burns and accompanying trauma in which the burn injury poses the greatest risk of morbidity or mortality.

- Burn injury in patients who will require special social, emotional, or rehabilitative intervention.

These specialized centers not only address immediate survival but also focus on long-term quality of life, which includes minimal scarring, mental/psychological health, rehabilitation, plastic surgery, and overall wellness.3

To be verified as a burn center hospital by the ABA, facilities are required to meet an extensive list of nearly 120 certification criteria, including the following6:

- A dedicated OR team with burn experience.

- A dedicated anesthesia team with burn experience available for the OR.

- Working with prehospital providers to improve patient care.

- All burn center medical staff must be available on a 24-hour basis.

- A comprehensive rehab program must be designed for the burn patient within 24 hours of admission.

- Providing rehab seven days a week for inpatients.

- Staff must participate regularly in public outreach programs.

Most burn injuries are preventable.3 Fire departments play an important role in fire prevention education, but no matter how vigilant our efforts are, there will always be a need for fire/EMS agencies to respond to these types of injuries. Education is key to providing the best outcome for these patients.

For more information on the Advanced Burn Life Support

Class, go to www.ameriburn.org/education/abls-program or call the American Burn Association at

(312) 642-9260.

Endnotes

1. American Burn Association. Burn Incident Fact Sheet. 2016. https://ameriburn.org/who-we-are/media/burn-incidence-fact-sheet/.

2. Advanced Burn Life Support Course Prover Manual. American Burn Association. 2018. http://ameriburn.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/2018-abls-providermanual.pdf.

3. Jeschke, Marc G.; van Baar, Margriet E.; Chourdhry, Mashkoor A.; Chung, Kevin K.; Gibran, Nichole S.; and Logsetty, Sarvesh. Burn Injury. NCBI. February 13, 2020. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7224101/.

4. Rice, Jr., MD; Phillip L.; and Orgill, MD, PhD, Dennis. Emergency care of moderate and severe thermal burns in adults. Retrieved August 2, 2021. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/emergency-care-of-moderate-and-severe-thermal-burns-in-adults.

5. American Burn Association. Burn Center Regional Map. Retrieved July 26, 2021. https://ameriburn.org/public-resources/burn-center-regional-map/.

6. American Burn Association, Burn Center Verification Review Program. Retrieved August 25, 2021. https://ameriburn.org/quality-care/verification/verification-criteria/verification-criteria-as-of-july-1-2017/.

Connie Pignataro, CFEI, retired from the fire service in 2021 after more than 18 years of service. She served as a lieutenant firefighter/paramedic with Oakland Park (FL) Fire Rescue and later as a fire inspector/investigator for Boynton Beach (FL) Fire Rescue. She has a bachelor of applied science degree in public safety administration.