The June 2016 release of a Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) Roll Call video, “Fentanyl: A Real Threat to Law Enforcement” (www.youtube.com/watch?v=HudxJRjkkeE), launched a paranoia across the public safety community that continues to grow. In the video, two New Jersey law enforcement officers describe an opioid exposure they believe nearly killed them. Additional media coverage of law enforcers and EMS providers who became ill while interacting with drug users has helped fuel widespread fears of fentanyl. These events have encouraged some responders to take excessive and extreme isolation precautions at scenes where opioids are present or prior to providing care to suspected overdose victims. As educated health care providers and all-hazards responders, it is time for the fire service to spread the facts and counter the myths about opioid exposures. We owe this duty to our fellow emergency responders. Fears of fentanyl and other opioids are greatly overblown and waste time and resources that interfere with our ability to serve the public.

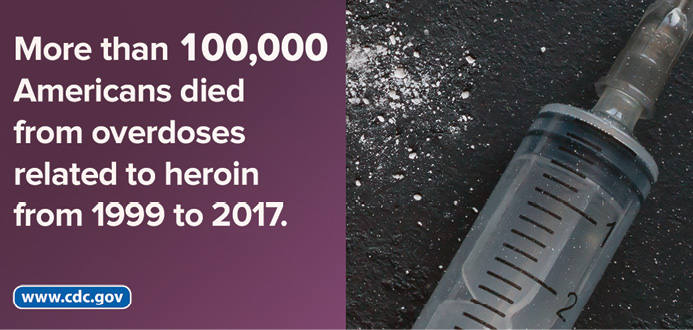

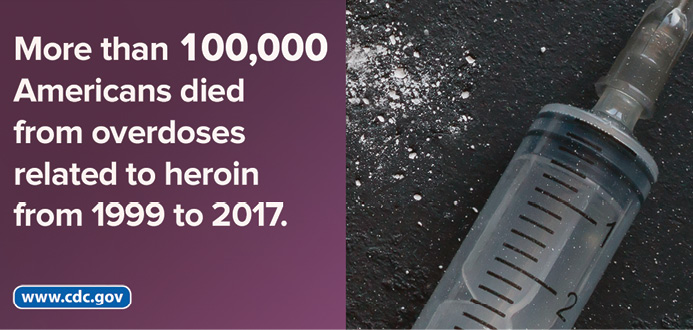

(1) Photo courtesy of the CDC.

The term “opioid” refers to a class of drugs used to reduce pain. Originally derived from opium, which comes from poppy plants, many variations of opioids including synthetic (man-made, such as fentanyl and carfentanil) exist. Opioids are administered by injection into the bloodstream, ingestion (swallowing), and sometimes snorting (absorption through mucous membranes in the nose). It is possible but not easy to absorb opioids through the skin. This necessitates mixing the opioid with an alcohol-based solution and gelling it into a cellulose patch.1 Wearable fentanyl patches take between three and 13 hours to deliver any significant amount of opioid into the bloodstream; years of research have yet to find any way to speed skin absorption of opioids.

RELATED: The Fentanyl Epidemic | Fentanyl: Not Just Another White Powder | Pain: How Do You Cope? What You Should Know About Opioids

There is no question that we are in the midst of one of the worst opioid epidemics in history; more than 130 Americans overdose and die from opioids daily.2 Yet, those deaths are never quick, as any experienced paramedic would most certainly confirm. In the course of treating pain, virtually every health care provider has once or twice inadvertently administered enough opioid to require assistance with ventilation and perhaps even a reversal agent. The effects of an opioid overdose are incredibly predictable and, untreated, take 40 minutes or more to result in death. This explains why bystander or first responder administration of naloxone saves so many lives. Loss of consciousness always precedes respiratory arrest and, in people who are unaccustomed to opioids, euphoria accompanied by nausea, vomiting, and dizziness are seen well before respiratory depression.3

These incredibly predictable signs and symptoms don’t correlate very well with responder reports being used to warn others about the dangers of exposure to opioids. In fact, the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) Health Hazard Evaluation (HHE) Program investigations of multiple workplace opioid exposures find little actual evidence of opioid absorption by emergency responders involved.4 More likely, according to the NIOSH reports, anxiety and panic symptoms were mistaken for opioid toxicity by the members involved and those around them. Yet, these instances have led multiple law enforcement agencies, including the DEA, to purchase naloxone kits for their entire workforce merely for the purposes of self or buddy aid should personnel be overcome during a response.

Two groups of toxicologists (specialists who study the effects of drugs on the human body) published a joint position statement in 2017 warning that the dangers of opioid exposure were being overblown. The American College of Medical Toxicology (ACMT) and American Academy of Clinical Toxicology (AACT) position statement (3) quantified the actual risks of exposure from touching, being sprayed in the eyes or face with opioid liquid or powders, or inhaling them. It turns out that the real risks of overdose or adverse health effects from an opioid exposure are quite low. Dermal exposure (contact with the skin) takes hours to be absorbed and, for any significant amount of opioid to be absorbed, requires exposing very large areas of skin surface for hours. Fentanyl or a fentanyl analog observed on the skin (liquid, powder, or pill form) can be quickly removed by brushing or washing with water. Even when removal is significantly delayed, opioids are very unlikely to be absorbed in quantities needed to produce symptoms. When washing hands or skin following an exposure to an opioid, do not use alcohol-based sanitizers, as they may increase absorption; soap and water are much safer. A single pair of nitrile gloves has been shown effective for protection while providing care to an overdose victim. (1) Although rarely used today because of the wide prevalence of latex sensitivities among patients and responders, latex gloves may not provide adequate skin protection against opioids.

Mucous membrane contact (spraying a liquid or powder in the eyes, nose, or mouth) is a possible route for absorption of opioids. Although direct facial contact with opioid containing liquids or powder is unlikely, the tendency to inadvertently rub an eye or touch the face after contact with an unknown substance has the potential to result in an exposure. This includes gloved hands. If there is a high likelihood of splashing liquids or aerosolizing powders, consider an N-95 mask; eye protection; and skin coverage with long sleeves, pants, or paper gowns. Unless these concerns exist, this additional personal protective equipment (PPE) is unnecessary. (1)

If opioid drug particles are suspended in the air, then inhalation exposure could be a concern. Although it is very likely that aerosolized carfentanil was used to overcome hostage takers at the Moscow theater in 2002 (3), it is extremely unlikely that you would encounter such a sophisticated dispersal device at any local event. If that were the case, a hazmat response would be appropriate. Another potential route of inhalation is field testing confiscated substances. Field testing suspected drugs is dangerous: it involves opening packages and handling unknown liquids and fine powders, something much more safely done in a laboratory.

Because of the escalating media hype and paranoia, the White House formulated recommendations for emergency responders during 2017-2018. In concert with numerous federal partners and emergency responders’ organizations, it produced a poster, “Fentanyl Safety Recommendations for First Responders,” and followed up with a downloadable video, “Fentanyl: The Real Deal,” to help subdue the perceived overreaction. Both are available at www.whitehouse.gov/ondcp/key-issues/fentanyl/. Other organizations have also published guidelines and recommendations for emergency responders.

The most current recommendations for protecting emergency responders from opioid exposures were published in Prehospital Emergency Care during 2018, consolidating best practices and evidence available to date. (1) These recommendations confirm that the likelihood of exposure is low but suggest a careful scene assessment with attention to the presence of visible powders or drug paraphernalia (which should not be handled or disrupted). For routine overdose responses, wear a single pair of nitrile gloves while providing patient care and wash hands with soap and water at the end of the call. Routine use of masks and additional PPE is not recommended. Manage powder exposures to the skin by flushing with large volumes of water or saline. Wipe dust on clothing with an alcohol-based wipe using a gloved hand, and launder the clothing. Exposed providers should shower as soon as practical. Wipe away visible dust or drug on a patient’s face before providing bag-valve-mask ventilation. Immediately assist ventilations of any person with respiratory depression; this should not delay administration of naloxone.

Emergency responders to opioid overdoses should work in pairs. If a suspected exposure occurs, call backup resources, begin appropriate decontamination, and monitor respirations and pupil size. Do not administer naloxone merely because of an exposure. If the responder becomes unconscious and has respiratory depression, then administer naloxone along with assisted ventilations. Transport to a health care facility as soon as possible. Launder clothing worn on the scene of an exposure as soon as possible, and providers should shower as soon as practical following an exposure.

I cannot overemphasize scene safety. Base actions to protect everyone on scene on actual risks. With sound scientific and medical response recommendations, we have the tools needed by the hundreds of opioid overdose patients we are called to see daily. We can smartly, safely, and carefully assess the risks and protect ourselves, other responders, patients, and bystanders. It’s time for the fire service to calm the fears being spread by social media and unscientific accounts of perceived exposures with facts about best practices.

References

1. Lynch MJ, Suyama J, Guyette FX. Scene safety and force protection in the era of ultra-potent opioids. Prehospital Emergency Care. 2018;22:157-162.

2. Scholl L, Seth P, Kariisa M, Wilson N, Baldwin G. Drug and Opioid-Involved Overdose Deaths–United States, 2013-2017. WR Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. ePublished: 21 December 2018. Online: www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/67/wr/mm675152e1.htm?s_cid=mm675152e1_w. Accessed January 10, 2019.

3. Moss MJ, Warrick BJ, Nelson LS, McKay CA, Dube P, Gosselin S, Palmer RB, Stolback AI. ACMT and AACT position statement: preventing occupational fentanyl and fentanyl analog exposure to emergency responders. Clinical Toxicology. 2018;56:297-300. Online: www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/15563650.2017.1373782. Accessed January 10, 2019.

4. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. NIOSH: Opioids–Field Investigations. June 15, 2018. Retrieved from www.cdc.gov/niosh/topics/opioids/fieldinvestigations.html.

MIKE McEVOY, Ph.D., NRP, RN, CCRN, is the EMS coordinator for Saratoga County, New York, and the EMS technical editor for Fire Engineering. He’s a nurse clinician in the cardiac surgical ICU at Albany Medical Center, where he also chairs the resuscitation committee and teaches critical care medicine. He’s the chief medical officer and a paramedic/firefighter for the West Crescent (NY) Fire Department.