By Marc Coenen

Photos by author except where noted

Sunday night, August 11, 2019. A night I will never forget. A fire erupts in an abandoned supermarket in Beringen, Belgium. I am the fire officer on duty. Two colleagues lose their lives. A third one is rushed to the hospital with severe burn injuries. I wander around the building that night, wracking my brain over just one question: What have I done wrong?

In February 2020, the Federal Public Service Home Affairs released the incident report. One of the conclusions reads as follows: “The different teams were deployed in a logical manner by the officer.” That was a relief, but my feeling of guilt did not disappear. On the contrary, it only grew. How can it be that, despite my logical and rational approach, the outcome was so terrible? My search for answers moved up a notch. At any cost, I had to understand the anatomy of that fatal fire.

Now, almost five years later, it is time for a progress report. What have I learned from all that research? Already in an early stage it became clear to me that I had not overlooked anything that fateful night in August. I had seen everything. I was only insufficiently aware that all that sensory input is formed, transformed, and even deformed by the thought processes in our head. Based on that fatal fire in Beringen, I want to clarify how we think under (time) pressure at a fireground.

A Night Like No Other

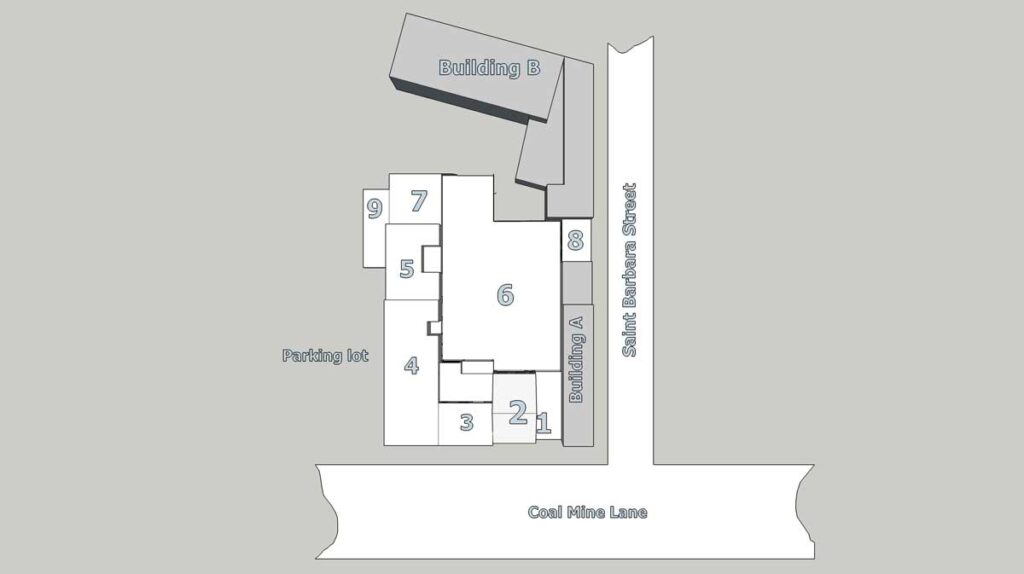

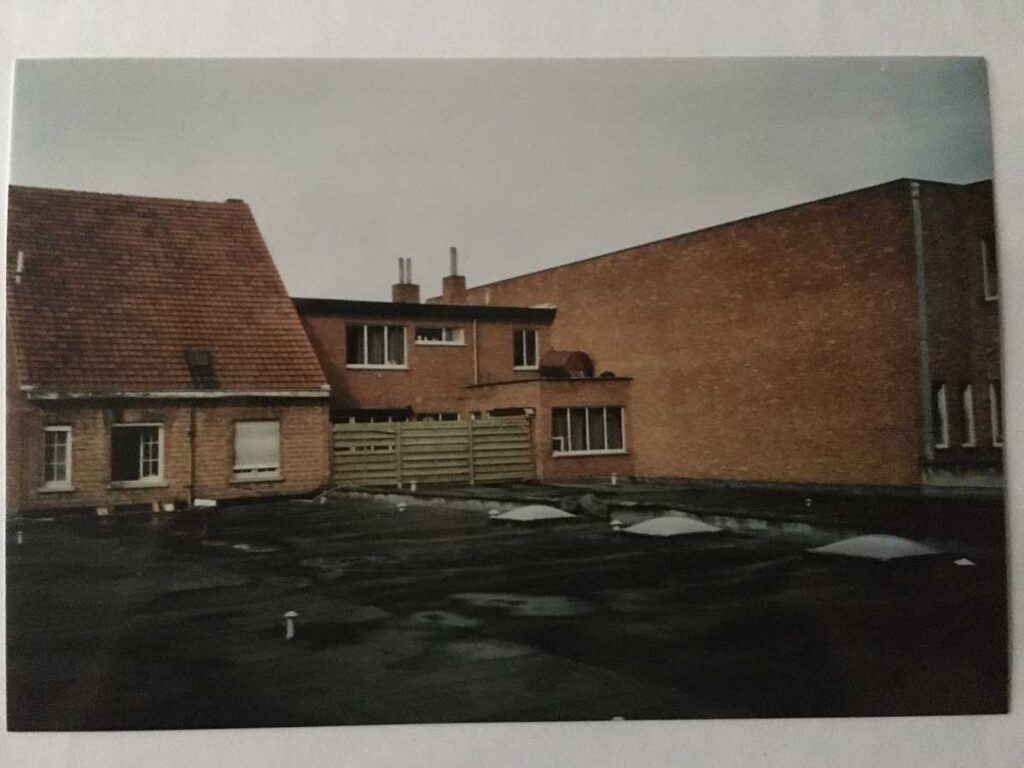

For several years, the dilapidated supermarket had been languishing in the centre of Beringen Mine (fig. 1). Like countless supermarkets all over the world, this building of roughly 50 x 50 m was the result of organic growth over a long period of time. It all started small toward the end of the 1960s with a neighbourhood store in building 3. This soon expanded and got hold of the entire neighborhood (fig. 2). The last renovation dates to 2007. On the ground floor, several load-bearing walls were opened up to expand the floor area of the supermarket (fig. 3). They also worked on the flat roof of building 6. Several layers of thick insulation boards were placed on top of the original tar and gravel roof, which in turn were covered by a new layer of tar and gravel. All the skylights and ventilation holes of the old roof were covered up (fig. 4).

Now what happened that fateful night in August? The incident report released by the Federal Public Service Home Affairs gives the following factual account of the course of events. In one of the retail spaces of this complex building of roughly 2,500 m2, a fire started in the worst possible place. The initial seat of the fire was located near where the concrete vaults of the ceiling of the retail space at the front of the building (building 3) connect to the wooden roof structure of a 830 m2 extension (building 6) added later. The fire managed to get into that roof structure. There, fuel is for the taking (including, among others, wood, plenty of insulation, and two layers of tar). The castellated beams—that is, steel beams with a repeating pattern of hexagonal holes—in the roof made it easy for the heat and the fire to advance through the ceiling toward the rear of the building. The back wall of the store was clad with chipboards (fig. 6). The high temperature inside the ceiling initiated their thermal decomposition. The decomposition gases released through this process of thermal cracking or pyrolysis literally pulled the fire out of the ceiling at the back of the building.

Anatomy of a Fatal Fire. What Have I Done Wrong?

Marc Coenen offers profound insights into the conscious and unconscious processes that shape our actions on the fireground.

The strategy that I had put together that night runs counter to the factual course. The process of decision making comes into question. That night I coincidentally passed by the boarded-up store just a few minutes before the emergency call was paged. From my car, I did not notice anything out of the ordinary. My focus was on the road and the little traffic ahead. Unconsciously, I brought to the fireground not only that recent past, but also the building’s history. In 2018, the Beringen Fire and Rescue Service had to deal with fires inside the building three times; all of them turned out to be arson. I assumed that we were dealing once again with arson, since all utilities (electricity and gas) had been cut off a long time ago.

When I arrived, I found a blazing fire at the front of the dilapidated supermarket. Luckily, the fire was not located deep inside the building. The greatest danger could be dealt with by an exterior attack. I kept in mind that there might be multiple seats of fire in the building, which is not uncommon with arson. While I conducted my initial size-up around the supermarket, I noticed that at several places light black-gray fumes slowly flowed from the building. I could explain perfectly what I saw. The raging fire at the front of the shop placed the whole structure in an overpressurized situation. The building was leaking like a sieve, and the smoke produced by the blazing fire is gently pushed out the building through all possible openings. All information pointed toward a ventilated fire development.

After the fire at the front of the supermarket has been extinguished, the pattern of the smoke did not change. The fumes just kept on flowing slowly from the building. In all likelihood, there was another seat of fire inside the building. Along the side of Saint Barbara Street, I sent in another team of firefighters. Shortly after entering the building, they reported that they had come upon a kitchen fire. My assumption was confirmed; this second fire was the reason why smoke keeps on coming out of the building. Around 2:50 a.m., I sent in a third team via the back of the building. These colleagues of Heusden-Zolder were instructed to check whether there were any remaining seats of fire and, if so, to extinguish them. When I sent them in, I received over the radio the message from the Saint Barbara Street team that they had extinguished the kitchen fire. They started to damp down.

Then, at 3:08 a.m., from one moment to the next, a fire that seemed under control unexpectedly changed into a nightmare. Pitch black smoke dropped out of the ceiling. The building became shrouded in complete darkness. The smoke was extremely hot and ignites immediately. The whole building lit up. The teams in Coal Mine Lane and Saint Barbara Street scrambled to safety. At the back of the supermarket, we were not so lucky. There, things were literally hell on earth, with fire everywhere and flames higher than your knees. One colleague would escape the inferno but was severely burned. Two other firefighters, however, lost their lives.

- Knowledge and Experience: Becoming the Senior Firefighter

- First Due: Preparing for Large Events

- Jeff Johnson: Making Critical Fireground Decisions

- The Seniors Must Teach the Juniors

Thinking About Thinking

Let’s focus on how we process information and subsequently make decisions. To gain insight into the thought processes inside our brain, I turned to the Israeli-American psychologist Daniel Kahneman. This winner of the Nobel Prize coined the acronym “WYSIATI,” which stands for ‘What You See Is All There Is.” It is a combination of the two modes of thinking in our head:

- A fast and unconscious mental process, or System 1

- A slow and conscious mental process, or System 2

System 1 contains all your automatic or unconscious mental processes. It operates quickly and automatically, with little or no effort at all and no sense of voluntary control. These include your

- Reflexes

- Intuitions

- Automatic thinking patterns

In short, it is your experience system. From the moment you are awake, automatic mental mechanisms are generating suggestions in the form of an endless stream of impressions, intentions, and feelings. Even if you wanted to, you cannot turn off that stream. The speed of that stream may be superfast, but the quality of the suggested ideas is far from splendid. More than once, the suggestions are imperfect, as the whole system is riddled with intuitive biases or systematic prejudices.

System 2 contains all the effortful mental activities that require attention and are disrupted when that attention is drawn away. They expend mental energy and are slow. Their operation is often associated with the subjective experience of agency, choice, and concentration. These include, among others,

- complex calculations (357 x 23 =?)

- planning (What are your plans for tomorrow?)

- self-control (I have to remain calm!)

- decision-making (Are we going to buy this house?)

Unfortunately, our conscious mental processes are born tired, and their basic state is the standby mode. One of their most important tasks is to monitor and maintain control of that endless stream of freewheeling impulses created by our experience system. Most of the suggestions are adopted with little or no modification. Only a few intentions and intuitions are suppressed. Contrary to what you might expect, conscious mental processes let countless fallacies slip through the cracks.

Here are two examples. Give the first answer that comes to mind:

A bat and ball cost $1.10.

The bat costs $1.00 more than the ball.

How much does the ball cost?

Like most people, you probably intuitively responded that the ball must cost 10¢. You better check that answer. If the ball costs 10¢ and the bat costs $1.00 more, then the bat costs $1.10, for a grand total of $1.20. The correct price of the ball is 5¢.

Another example. Fill in the blank:

John’s mother has three children.

Their names are May, June, and . . .

Intuitively you fill in July. But her third child is of course John.

As stated earlier, conscious mental processes regularly slip up. When your experience system immediately provides a very logical-sounding answer, then your System 2 barely bothers to check it. That is all nice to know, but what has this got to do with firefighting? WYSIATI is also playing in your mind when you are plotting the strategy on a fireground.

From Information to Deception

The ideal situation for making informed decisions is having all relevant information at your disposal. The emphasis is on relevant. You do not need all the information. In fact, an overabundance of information only makes harder for you to know what precisely you should be looking at. And in principle, all the data you have gathered are reliable. That is, for example, the case when you are planning to buy a new washing machine.

The availability of information at an incident scene is completely different, certainly at the start of the incident. Often, crucial information is missing or the data at your disposal are wrong or incomplete. That is how everyone that night in Beringen ended up in the wrong type of incident. On the basis of the cues emitted by the fire, we assumed we were dealing with a ventilated fire development. In hindsight, however, the real problem was a structure fire in a flat roof. As I had passed the building only a moment before the emergency call was paged, I was led to believe that the fire had only just been lit. Afterward, it became clear that at my time of passage, the fire was already burning for half an hour inside the building. A surveillance camera caught the first cues of fire already at 1:38 a.m. And for an empty supermarket, the fire load surpassed by far the average, as the interior finishing was made of an excessive amount of fiberboards and sandwich panels (fig. 7).

It is only a small step from this kind of information to deception. When you unleash a human brain on limited information or a sequence of isolated events, it will always recognize patterns and impose causal connections, even if there are none. That is why the most idiotic conspiracy theories sell worldwide like hotcakes. In the Netherlands, conspiracy theorists deliberately set fire to 33 phone masts in 2020. According to them, the outbreak of the coronavirus was not the consequence of the unhygienic practices in Wuhan’s Huanan seafood and wildlife market, but was due to the rollout of 5G mobile phone services in the Chinese province of Hubei, of which Wuhan is the capital. In 2020, however, 5G had not yet been rolled out in the Netherlands.

With WYSIATI, everything revolves around the logical consistency or coherence of the story. Applied to our strategy, neither the amount nor the quality of the information counts for much. If your associative brain succeeds in immediately constructing a consistent and plausible narrative from your perceptions, then the ball is rolling. When subsequently your ideas appear to be confirmed, then your subjective confidence in that narrative grows and you become blinded by your own strategy. Our tendency to coherence is so strong that the balance easily leans over to narrative fallacy. For quite some time, situational awareness has been the buzzword at fire academies and in emergency services. I am of the opinion that narrative fallacy and situational awareness are two sides of the same coin. And that coin is situational influencing of our adaptive unconscious.

The Predictive Brain

About 10 years ago, the Predictive Coding Theory was formulated in neurology and cognitive psychology. In this theory, the brain is one big predictive organ. Just as the stomach digests food or the heart pumps blood through the body, the brain’s job is to generate and to check predictions. These predictions, however, are not about the future but about the present: what is happening in the outside world that explains the input that is now pouring in. Our brain manages an internal model or simulacrum of the reality around us that it is constantly updating by checking sensory and other input against the situation we are in. Our brain finds itself in the middle of a love triangle. It controls all our thoughts and actions from within the triangle:

- Environment

- Internal physiological condition of the body or interoception

- Prior experience

From birth onward, we start to make sense of the environment we live in. In our brain, concepts arise as statistical regularities or recognizable patterns, and to each one of them we humans have given a name: mother, table, dog, fire…

From the start we also get to know and recognize the things that take place inside our body. We learn to interpret muscle tension, heart rate, breathing, or pain, and give these things meaning. A growling stomach signals it is time to eat, and I do not have to tell you what you have to do when your throat is dry. Interoception, or the sense of the internal physiological condition of your body, does a lot more than signalling physiological needs like hunger and thirst. It also directs the behavior of firefighters on the fireground. I am referring to your gut feeling. You know that feeling all too well. In a particular setting, you suddenly feel uncomfortable and decide to retrace your steps. You do not trust the situation, although you cannot pinpoint what exactly is wrong. For example, you are standing in the staircase of a burning building. For some unknown reason you do not cross with your team to the adjacent room that contains the seat of the fire that has to be extinguished. Then the ceiling of that room collapses and, of the entire building, only the staircase is still standing. The reverse is also possible, and far more dangerous. In such an instance, you incorrectly recognize something as safe. Interoception can mislead you during interventions, often with dramatic consequences.

What is happening here? You have recognized something subconsciously. Or more precisely, your adaptive unconscious has (not) picked up on something threatening in the environment and translated it into a (gut) feeling. This recognition happens very fast, and even subliminally or under the radar of consciousness when your life is in danger.

Then there is the third and final factor: memories of similar situations or, in other words, your experience. Everything we do and think arises from the combination of a (gut) feeling in a certain situation or context and prior experiences. From the neurological patterns initiated by these three factors, our associative brain continuously generates predictions or best guesses about the causes of these electrochemical signals. It is always checking and adjusting these predictions when necessary.

And do we do all of this consciously? Situational awareness creates the impression that we humans have everything under control with our conscious thinking, or at least that we can get it under control. Our behavior is, however, more directed by the unconscious. The evidence is compelling. Experiment after experiment shows that our conscious mind always lags behind. Our unconscious is already preparing each action or behaviour about 800 milliseconds in advance (almost a full second!) while the conscious decision is recorded only 350 milliseconds before the action.

All conscious behavior, then, is prepared unconsciously, and our subjective experience of the conscious decision to act is little more than a sham decision. However, our conscious mind does a great job in hiding the fact that it misses the start over and over again by creating the illusion that it is at the origin of all our decisions and subsequent behavior. Often we do not know why we make certain choices or do certain things. For example, if you put four identical pairs of nylon stockings in a row, 40% of research participants will take the far-right pair. Should you ask them why they have chosen that particular pair of stockings, they will answer that those are more beautiful, the texture is better, or the color nicer. Based on countless tests, psychologists are convinced that we make a decision or have an opinion on the basis of unconscious reasons, after which our conscious mind starts to rationalize that judgment and comes up with good reasons for it.

The most striking difference between the conscious and unconscious mind is their processing capacity, where our consciousness stands out in a negative manner. Its capacity is seven letters or numbers, plus or minus two, and that is all. The computational power of our conscious mind is 60 bits per second. That of the unconscious mind is no less than 200,000 times bigger than that of your conscious awareness: about 11.2 million bits per second. Now which Ipad do you prefer to use at an incident scene: A device where the data transfer in the working memory happens at the speed of 11.2 million or 60 bits per second?

Now to the Fireground

That is the Predictive Coding Theory in a nutshell. Everyone, from firefighter to officer, is unconsciously making predictions all the time at the incident scene regarding the situation he finds himself in. On the basis of this theory, you can explain why so many firefighters have perished—and many more will perish—on a fireground with the following sensory cues:

- good visibility inside

- low temperature inside (50 to 60 °C)

- smoke light in color

- smoke that barely flows

Based on experience and the relatively safe impressions, we interpret those signals as a manageable fire of limited power in the growth or decay stage of a ventilated fire development. In the past, we have managed to extinguish such fires without any problem with our nozzle techniques. Why should it be different this time? That is the prediction that our brain generates automatically. Should you find yourself, however, in the scenario of a pulsating fire, a fire gas ignition or a structure fire, then without even noticing it, you are tempting fate. In those situations, that light-gray smoke has to be assessed completely differently. Only after the intervention is over will you know whether your assessment of the intervention type was correct. We walk into such traps with our eyes wide open, like our Canadian colleagues did on January 21, 2006, in Montréal. An emergency call for a suspicious odor in a small block of flats goes bad. Cold smoke gases find an ignition source and set an entire residential block ablaze. A fire officer loses his life.

What does this all mean for our intervention strategy? Recognizing something unconsciously or your first impression upon arriving at the incident scene compels you to decide. In the words of the American psychologist Gary Klein, our intervention strategy is based on a recognition-primed decision. This refers to a thought process that basically consists of an intuitive recognition on which only a minimal conscious check is conducted.

How does this thought process work? Somewhat like a slide loader. (I know, that is outdated technology, but, unconsciously and unwillingly, my age starts to shimmer through.) The idea is that of all the incidents you have attended to, your brain has made slides, and those slides are stored in a mental slide loader. Together, they form the unconscious mental background against which you consider the handling of the new incident. In response to the environment and based on your (gut) feeling and experience, a certain cluster of nerve cells in your brain begins to send signals to another cluster in a certain pattern, for a certain time, and at a certain frequency. There are always several neural networks inside your brain competing for the upper hand, but ultimately one of these networks will gain the upper hand and formulate the prediction regarding the unfolding situation at the incident scene.

Lightning fast, that similar situation comes to mind. The serial evaluation of options, or browsing through your slides, is an unconscious or intuitive mental activity. That pattern recognition results in a strategy over which your conscious mind exerts only limited control. Consciously, you consider whether or not that strategy will work. If yes, then the process of looking for an effective strategy comes to an end, although better strategies might be possible. But you simply look no further, because you have found a strategy that you know (or believe you know) will work.

I find this hypothesis convincing. In the fatal fire of De Punt on May 9, 2008 (Drenthe, the Netherlands), that intuitive thought process is clearly discernible.

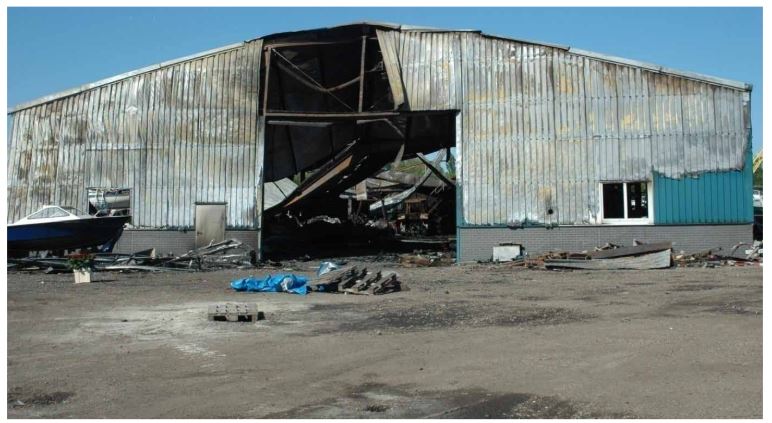

■ That afternoon, the fire engine leaves the fire station at 2:14 p.m. in response to a house fire. However, it concerns a fire in an indoor storeroom with a depth of 15 m that is located in a large hangar (25 m × 75 m) in which recreational boats are maintained and stored.

■ Two minutes later, when the fire truck is approaching a roundabout at the rear of the hangar, the crew sees a thick layer of brownish-yellow smoke quietly flowing out the rear of the hangar.

■ The warrant officer in the fire truck scales up to “medium fire.” An additional unit and the officer on duty are dispatched to the fireground.

■ The fire truck arrives at the scene around 2:18 p.m. In front of the hangar, the situation is completely different. There is hardly any smoke; just a few patches of smoke are visible at the back of the hangar. A police officer informs the firefighters that there is a car burning in the back of the hangar. The warrant officer assesses the situation again.

■ The house fire, which only a few minutes ago was intuitively scaled up to a “medium fire,” is now downsized to a car fire by that same intuitive thought process.

■ After the warrant officer has given the formal order, “explore and extinguish any fires,” four firefighters enter the hangar and the warrant officer starts his 360° size-up around the building.

■ At 2:21 p.m., the warrant officer scales up to “big fire.” The entire hangar is ablaze and his three colleagues are still inside the building. The three firefighters perish.

Typical of this incident are the big differences between the cues picked up by the warrant officer when he and his colleagues were driving up to the fire and those picked up upon arrival on the fireground due to the pulsating fire in the indoor storeroom. Time and time again, the warrant officer assessed the sensory cues intuitively on the basis of experience and gut feeling. His strategies form, as it were, a series of consecutive but completely distinct WYSIATIs. The scaling up during the approach is no longer relevant when they have pulled up in front of the hangar and the incident is intuitively reduced to a car fire. That is exactly how intuitive thought processes work: they neglect ambiguities and suppress doubts. Central in the decision-making process stands the logical consistency of the narrative, and that is based on whatever information that happens to be available, even when the information is limited and flimsy.

What, then, is the difference between the fire in De Punt and that of Beringen? De Punt is a sequence of WYSIATIs. As such, that fire is precisely the opposite of my intervention. Beringen was one overextended WYSIATI that I was able to enrich with an ever-increasing amount of details. But that did not make the scenario more likely. On the contrary, from the beginning onward my assessment of the situation was completely flawed.

What do we have to keep in mind at a fireground? More than we realize, our actions during incidents are directed by unconscious thought processes. Instead of around situational awareness, everything revolves around situational influencing of the adaptive unconscious by cues from the environment, our (gut) feeling, and experience. Out of this input, our associative brain automatically and unconsciously creates a prediction or a best guess. This results into a behavior or a strategy that our conscious mental processes barely check. That is particularly the case when that behavior or strategy appears to be logically sound. And in the complex, dynamic situation of the fireground, that behavior or strategy can be totally wrong—with all the tragic consequence this entails.

Marc Coenen, PhD, an Egyptologist by training, started his career in the fire service as a volunteer officer in the Aarschot Fire Service. Now he is a career officer of the Fire and Rescue Service of South-West Limburg, attached to the fire station of the city of Beringen, Belgium.

Selective bibliography

All information on the Beringen fire and how the mind works, are taken from M. Coenen, Anatomy of a Fatal Fire. What Have I Done Wrong?, Tulsa 2024, and complemented with insights from:

- J. Bargh, Before You Know It. The Unconscious Reasons We Do What We Do, London 2017.

- L. Feldman Barret, How Emotions Are Made. The Secret Life of the Brain, London 2018.

- M.S. Gazzaniga, Who’s in Charge? Free Will and the Science of the Brain, London 2016.

- D. Kahneman, Thinking, Fast and Slow, New York 2011.

- G. Klein, Sources of Power: How People Make Decisions (20th Anniversary Edition), Massachusetts 2017.

- V.S. Ramachandran, The Tell-Tale Brain. Unlocking the Mystery of Human Nature, London 2012.

- A. Seth, Being You. A New Science of Consciousness, London 2021.

- N.N. Taleb, The Black Swan. The Impact of the Highly Improbable (2nd ed.), New York 2010.